As early as September 1797 the general had informed Talleyrand that the Maltese were "well disposed to us and thoroughly disgusted by the Knights." An agent named Poussielque was subsequently sent to the island where he made contact with some surprisingly high-ranking dissidents including the artillery commander and the engineer in charge of fortifications and the water supply. Not surprisingly therefore the French landing on 10th June 1798 was virtually unopposed and surrender negotiations commenced less than 24 hours later.

British units were selected for the event on the basis of their willingness not just to comply with fairly rigorous standards of dress and equipment, but also to operate in role from dawn to dusk throughout what was planned as a week-long event. Whilst the flrst stipulation

obviously speaks for itself, the second was by far the more important since a successful historical (or theatrical) interpretation requires the ability to consistently play a part

convincingly.

A small military staff was put together by invitation and participating re-enactor units and individuals assigned to composite companies according to uniform and role:

No.2 Coy. 16th (Buckinghamshire) Regiment Rifle Coy. 5/60th Rifles This was only the beginning of course, for the battalion thus formed had to learn to work together. A point often overlooked by re-enactors more used to operating in platoon-sized units is that larger formations don't simply make it possible to practical proper tactical evolutions as well as the more basic squad drills - they actually demand it. That well known cry of "Follow me!" may work very well with half a dozen stalwarts and Rover the dog, but it don't work with a

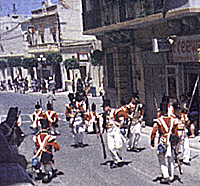

real battalion. Consequently arrival at St.Elmo Barracks, Valetta was followed by a necessary period of shaking down and a gentle introduction by Sergeant Major Peacock of the 68th to some of the more basic bits of David Dundas' Principles of Military of Military Movements. It would have been criminal not to and after a surprisingly short time the battalion actually began to look like British soldiers.

It was hell working on the regimental staff too. Since everyone was to be "on duty" all day and well into the evening, daily orders had to be prepared advising company and detachment commanders what they were supposed to be doing, where and when. Straightforward says you, but

plans as some fool once pointed out rarely survive contact with the enemy, or for that matter a political crisis on Malta which produced real riots in some of the districts where we were supposed to be staging some action.

Then at the end of it all and fortified only by chewing on a particularly fiery local sausage and sucking lemons, the disjointed notes have to be turned into coherent written orders, copied (by hand of course) and distributed to the various billets in time for reveille. Thank God for those little IKEA pencils and don't it just give you a very real insight into the staff work which must have gone into producing some of those famous victories.

But you, gentle reader probably don't want to know. You just want the exciting bits and the famous victories. The French, being the French and always ready to dive in and snap up the best of it were all over the place and at one stage even had to beat a hasty retreat from some real rioters - which was probably taking re-enactment just a little too far.

The first bit of action for British arms came when the Rifle Company was shipped across the Grand Harbour by HMS in order to liberate Vittoriosa (alias Birgu) from the French. Captain N. of the 5/60th, the officer commanding the expedition returned the subjoined report, modestly

described as being rather in the style of Napier:

After receiving reports from the local guerilla that the French detachment is still in Senglea the Light Brigade pushed on to that town. The French detachment delivered battle in the town itself, but was largely defeated and scattered, losing 4 prisoners to the Light Brigade. Own losses were 4 lightly wounded. The French detachment consisted of Maltese unit, the 18th Line regt. and an Italian regiment of voltigeurs.

Next day it was back to St. Elmo and then across to Zabbar for a rendezvous with the Rifle Coy. and the 1st Provisional Battalion's final fixture on Malta. This time it was to be a re-enactment of an incident in which a French foraging expedition came busting into town, got ambushed and was then chased all the way back to Vittoriosa (or Birgu).

Since Lieutenant Colonel Moon was unavoidable detained at St. Elmo on matters of some importance, I had the honour to command the 1st Provisional Battalion on this happy occasion, together with a briskly conducted landing party of British sailors, the Cirenadiers of K.K. IR Nr.2 and some detachments of Maltese.

Seeing the French approaching up the high road from Vittoriosa, I deployed my forces around the great gatehouse which forms the principal entrance to Casal Zabbar. The Rifle Coy. commanded by Captain N. of HM 5/60th took post in a low-wailed garden on the left, while the Bluejackets lay on the right. The ambuscade was a complete success. The French vanguard advancing through the gate were met with a perfect hail of musketry from two sides and charged in front by the Light Coy. commanded by Captain Yuill of HM 68th.

Unable to stand, the French fell back at once upon their main body, which comprised at least four companies and a gun. Alerted by the flring they had halted and were formed across the high road. Being determined to second this auspicious beginning I ordered an immediate advance and formed the battalion with two companies and the Rifles on the left, the Light Company and some Maltese in the centre, and the Grenadiers on the right, supported by the Bluejackets and the remainder of the Maltese.

At length, despairing of his situation, and evidently not a little concerned at the prospect of failing into the hands of the Maltese insurgents, the French general surrendered at discretion and we thereupon seconded this success with a swift march upon Vittoriosa

and gained possession of this important post without opposition.

Re-Enactment Aims

Having followed the narrative thus far, you might wonder what the point of this article might be. Recently there has been a considerable exchange of correspondence in another place. as to the aims of re-enactment. This has largely centred around the question of clothing and equipment, with a clear imputation that any who fail to achieve perfection are just playing, and

presumably therefore to be consigned to the outer darkness, or at the very least not taken seriously. On the face of it this argument might appear unassailable, but in fact it misses the point. It is extremely important to wear accurately reproduced kit, but if this is the sole criteria by which an impression is to be judged it might as well be hung on a dummy in a display

case.

If re-enactment is to have any vality it should stretch the Individual Interpreter and at least provide him with some kind of isight into his chosen role. The Malta expedition did Just that. It was hard going at times and the event organisation could have been better, but I've not dwelt on that because taken as a whole Malta expedition was a remarkable success. This was by any standards a serious bit of re-enactment. A number of small but perfectly formed groups

came together in a superb setting - you can't ask for better than Fort St. Elmo - to experience something which if not unique was certainly a long way removed from the usual hour long encounter on a plain field. Like two fictional riflemen of some notoriety, the 1st Provisionai Battailon will march again.

Mr. Hollins, this Journal's distinguished AustroHungarian correspondent was a touch premature in declaring that re-enactments of the sffrring events of 1798 were now at an end unless someone was prepared to go to Egypt. As every schoolboy knows (?) the Corsican Bandit stopped off in Maita on his way to the desert sands. His story of course was that he only wanted to stock up on fresh food and water before heading into Four Feathers country, but the Grand

Master of the Knights of St. John didn't believe a word of it. It didn't take the brains of an Archbishop, let alone a Grand Master to flgure out that Buonaparte actually had something

much more sinister in mind.

Mr. Hollins, this Journal's distinguished AustroHungarian correspondent was a touch premature in declaring that re-enactments of the sffrring events of 1798 were now at an end unless someone was prepared to go to Egypt. As every schoolboy knows (?) the Corsican Bandit stopped off in Maita on his way to the desert sands. His story of course was that he only wanted to stock up on fresh food and water before heading into Four Feathers country, but the Grand

Master of the Knights of St. John didn't believe a word of it. It didn't take the brains of an Archbishop, let alone a Grand Master to flgure out that Buonaparte actually had something

much more sinister in mind.

Some dramatic changes then followed as the Knights' feudal rights and prerogatives

were swept away and replaced by a modern legal system and political institutions. It all turned sour very quickly of course and a popular uprising began towards the latter end of 1799.

The French garrison was penned up in the towns and in March 1800 two British battalions, the 30th and 89th Foot under Thomas Graham were shipped across from Sicily together with a couple of Neapolitan battalions ("fine stout men, but badly officered, and wretchedly clothed"). Three

more British battalions; 1/35th and 2/35th, and the 48th then turned up from Minorca together with Major General Pigott and the French were eventually starved into submission on the 5th September.

Some dramatic changes then followed as the Knights' feudal rights and prerogatives

were swept away and replaced by a modern legal system and political institutions. It all turned sour very quickly of course and a popular uprising began towards the latter end of 1799.

The French garrison was penned up in the towns and in March 1800 two British battalions, the 30th and 89th Foot under Thomas Graham were shipped across from Sicily together with a couple of Neapolitan battalions ("fine stout men, but badly officered, and wretchedly clothed"). Three

more British battalions; 1/35th and 2/35th, and the 48th then turned up from Minorca together with Major General Pigott and the French were eventually starved into submission on the 5th September.

According to the Treaty of Amiens the island should then have been handed back to the Knights in 1802, but instead the British garrison stayed put for over 150 years. It is difficuit therefore to underplay the significance to the Maltese people of Napoleon's invasion. This year is not merely the bicentennial of a famous victory somewhere; modern Maltese history effectively began 200 years ago. Not surprisingly an ambitious (perhaps a touch overambitious) programme of events involving re-enactors from all over Europe was organised by the 27th Division.

According to the Treaty of Amiens the island should then have been handed back to the Knights in 1802, but instead the British garrison stayed put for over 150 years. It is difficuit therefore to underplay the significance to the Maltese people of Napoleon's invasion. This year is not merely the bicentennial of a famous victory somewhere; modern Maltese history effectively began 200 years ago. Not surprisingly an ambitious (perhaps a touch overambitious) programme of events involving re-enactors from all over Europe was organised by the 27th Division.

For obvious reasons the Naval (HMS), Royal Artillery and Yeomanry contingents operated

semi-independently, but this wasn't to be the case with the infantry. A common criticism of re-enactment is the undeniable fact that it is quite impossible to represent a battalion with a dozen bodies. Instead, therefore, full advantage was taken of the extended concentration to form

all the infantry into a single Provisional Battalion, which, weak as it was, would at least be capable of behaving like a proper military formation.

For obvious reasons the Naval (HMS), Royal Artillery and Yeomanry contingents operated

semi-independently, but this wasn't to be the case with the infantry. A common criticism of re-enactment is the undeniable fact that it is quite impossible to represent a battalion with a dozen bodies. Instead, therefore, full advantage was taken of the extended concentration to form

all the infantry into a single Provisional Battalion, which, weak as it was, would at least be capable of behaving like a proper military formation.

Light Coy. 68th (Durham) Regiment

No.1 Coy. 23rd (Royal Welch) Fusiliers

No.1 Coy. 23rd (Royal Welch) Fusiliers

45th (Nottingham) Regiment

37th (Hampshire) Regiment

47th (Loyal) Regiment

95th Rifles

2/1CGL Rifles

Maltese Light Infantry Add to this some rather suspect staff work at higher echelons and you have a very interesting situation where nothing deflnite is known of the following day's activities until its thrashed out at a multi-lingual conference stretching far into the night.

Add to this some rather suspect staff work at higher echelons and you have a very interesting situation where nothing deflnite is known of the following day's activities until its thrashed out at a multi-lingual conference stretching far into the night.

First Action

First Action

Being order'd the Light Bde (sic) consisting of Det. 5/60th, 95th, 2KGL, and Maltese Light Infantry disembarked at Birgu. The French troops being weak in numbers and occupied with quelling the local guerilla, I decided to take the Fort. After a sharp skirmish, the French

retreated into the town. In the ensuing street fighting the Light Brigade was ably assisted by the local irregulars. The French afterwards retreated to Senglea. The conduct of the Light Brigade, NCOs as well as other ranks was very good. We only suffered 1 slightly wounded...

Unfortunately it soon transpired that the French had not been quite so comprehensively dished as was originally though. Vittoriosa was reoccupied and at 20 minutes notice the gallant Captain had to turn around and recross the harbour for a second day's skirmishing. In the

meantime the rest of the 1st Provisional Battalion proceeded to the neighbouring island of Gozo for a rather neat little reenactment of a skirmish at Casal Nadur, after which the Citadella at Victoria was stormed in fine style, the British colours hoisted over it and the island liberated.

Unfortunately it soon transpired that the French had not been quite so comprehensively dished as was originally though. Vittoriosa was reoccupied and at 20 minutes notice the gallant Captain had to turn around and recross the harbour for a second day's skirmishing. In the

meantime the rest of the 1st Provisional Battalion proceeded to the neighbouring island of Gozo for a rather neat little reenactment of a skirmish at Casal Nadur, after which the Citadella at Victoria was stormed in fine style, the British colours hoisted over it and the island liberated.

Finding the French left uncovered, I directed the Grenadiers to occupy a low terrace whereby they might enfllade the enemy in perfect security. This measure seemed to stagger the foe and flnding the French commander in no ways disposed to come forward, I resolved to attack him

instead and placing myself at the head of No.2 Coy. ordered a general advance. At flrst the French seemed inclined to dispute the matter and for a time fought hand to hand, but upon their left giving way, a general retreat commenced down the high road towards Vittoriosa. On two several occasions they attempted to make a stand, but their ground was ill-chosen and their flanks rapidly turned by the Light and Rifle Coys.

Finding the French left uncovered, I directed the Grenadiers to occupy a low terrace whereby they might enfllade the enemy in perfect security. This measure seemed to stagger the foe and flnding the French commander in no ways disposed to come forward, I resolved to attack him

instead and placing myself at the head of No.2 Coy. ordered a general advance. At flrst the French seemed inclined to dispute the matter and for a time fought hand to hand, but upon their left giving way, a general retreat commenced down the high road towards Vittoriosa. On two several occasions they attempted to make a stand, but their ground was ill-chosen and their flanks rapidly turned by the Light and Rifle Coys.

Adjutant, 1st Provisional Battn. Re-enactment ought to be much more. At the bottom end of the scale it is ail too frequently no more than a bit of escapist entertainment for both participants and punters, but it is quite Invidlous not to draw a distinction between this and the serious historical interpretation practiced at the top end of the scale.

Re-enactment ought to be much more. At the bottom end of the scale it is ail too frequently no more than a bit of escapist entertainment for both participants and punters, but it is quite Invidlous not to draw a distinction between this and the serious historical interpretation practiced at the top end of the scale.

Back to Age of Napoleon No. 28 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1998 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com