Unchecked numbers of accompanying women could, however, prove a great hindrance to an armies movement and supply. In 1793, for example the commissaires and Representatives of the people with the Armee du Nord wrote to Paris that [2] : The letter goes on to complain that at the barracks of Douai, there were 3,000 women and only 350 men, leaving little room for new units. Needless to say soon afterwards the National Convention revoked its revolutionary decree allowing soldiers to freely marry whomever they wished, and only a prescribed number of official soldiers wives were permitted to follow the French army.

A similar situation existed in the British army, whereby six wives per company of one hundred men were allowed to accompany the army oversees. Those six could officially draw rations and make a little money through washing and mending clothes. Women without children were sometimes preferred, but in most cases the factors of pregnancy or having children did not play a part in the decision to allow them to embark. It was only in the Rifle Corps that it was specifically layed down that women with more than two children were not permitted to accompany the army. [4]

Women were chosen by pulling a "to-go" or "not-to-go" ticket out of a hat, the procedure taking place in the Pay Sergeants room at barracks when the time came to sail abroad. The women were called forward one at a time in order of seniority to draw out a ticket before the expectant onlookers. Doubtless much hysteria, both through joy and despair accompanied the event. Both the lucky and the unlucky wives would then march with the regiment to the docks, and many distressing scenes resulted. Glieg, a Subaltern of the 85th recounts in his autobiography the story of Duncan Stewart, a young Highlander who after marrying secretly without his father's consent, took the King's Shilling while drunk, after seeking the Dutch Courage to tell his father of the deed. He was taken from Edinburgh to Hythe to join a draft of the 85th leaving for the peninsula. He did, however, gain permission to send for his wife, but after making the journey from Scotland alone while in the advanced stages of pregnancy she was unlucky enough to draw a "not to go" ticket. Mary (Duncan's wife) was distraught and was permitted to accompany the troops to Dover, but died in child birth while on the way. [4]

Those who were not so lucky, could obtain a certificate from a Justice of the Peace in the area of embarkation to assist them to return

home. The overseers of the poor at the places they travelled through were compelled to give these women I fi d. per mile for the number of miles until her next stop, not in excess of 18 miles.

In the French army six Vivandieres (sellers of necessary supplies, most notably liquor and tobacco) and six Blanchisseuses (literally washer-women who were usually sergeants wives) per infantry battalion, and four of each for cavalry regiments were allowed to follow the army, being given a certificate and (in the case of Blanchisseuses) entitlement to rations. In some armies a badge of status was worn, usually a simple inscribed medallion, while the Army of the Mosselle issued tin plaques to be worn on the left arm bearing the inscription "Blanchisseuses (or Vivandi6re) de Battalion". [6]

Common law wives and mistresses, however, persisted in the French army in huge numbers, and in 1796 Napoleon was forced to make examples of the worst women for offences such as plundering.

Mercer, speaking of the British army during the Waterloo campaign noted that "The number of servants, sutlers, stragglers and women was incredible and added not a little to the general confusion". [7]

Women were good for an army's morale, but bad for its supply, movement and discipline and at the end of the day those in command could only prescribe orders to control the women, rather than do away with them altogether.

In the British army, for example, both officers and men usually obtained donkeys or wagons to transport their wives and lovers, a practice that could not be stopped, but one which the high command tried to regulate. In 1812, for example, during the retreat from Burgos after repeatedly telling the women not to ride ahead of the troops and block the roads, two of their donkeys were shot in order to forcibly stop them. Similarly an order of the Duke of Wellington dated 3rd of August 1809 ruled that the women who followed the army were not to be permitted to buy bread from the villages through which they passed, as they were taking the very bread the commissariat staff would purchase for the men's rations. It was also ordered that the women should not steal the vegetables from the locals fields and gardens so as not to lose their support. [8]

Life

Life for the women who followed the army was by no means easy. For the wives an oversees journey with their men would be a cramped and disease ridden affair (taking three weeks to get to the Peninsula from Britain, for example) and then upon arrival in a foreign land, the women faced either bad or no billets, (as Mary Anton, a wife of a soldier of the 42nd did, being billeted in a dilapidated convent in Ranturea in 1813 [9] ) and the possibility of being left behind at the place they disembarked. From then on the women would face hunger, disease, violence and extreme weather conditions, often in the open air, under home-made bivouacs, or in cramped tents with other soldiers, and as the Anton's found, the men they shared with were all suffering from an irritating skin disease caused by being unable to remove their clothing. Wherever possible attempts would be made to find proper billets for the army wives when staying in a town or village, even though they had no specific rights to accommodation but this was not always possible, and the soldiers obviously took priority over the women and children.

Soldiers had been assisting her by carrying the child but they too had grown to weary to assist and the woman carried on dragging her child "even though she was like a moving corpse herself. Eventually the child was too exhausted even to cry and they both

sank down "to rise no more". [10]

Some women were more fortunate. One "sturdy and hardy Irishwoman" named McGuire gave birth while on the retreat and both mother and child survived. [11] Harris' most vivid description of the women, however, is of the rear of the army: "Far away in front I could just discern the enfeebled army crawling out of sight, the women huddled together in the rear, trying to get forward amongst those of the sick soldiery who were unable to keep up with the main body. Some of these poor wretches cut ludicrous figures for although their clothing was extremely ragged and scanty, and their legs were naked; they had the men's greatcoats buttoned over their heads. They looked like a tribe of travelling beggars". [12]

Similar accounts of hardship come to us from Napoleon's retreat from Moscow in 1812. Madame Dubois, for example, the wife of a regimental barber gave birth in a wood with a heavy snow failing and with twenty degrees of frost. She was able to gain the assistance of a doctor as well as two blankets from dead men, while the Colonel lent her his horse and greatcoat - the child was wrapped in a sheepskin. Compared to many she was very fortunate. [13]

The camp follower did not, however, merely follow the army (although undoubtedly there would have been many hangers-on who literally followed; prostitutes, various trades people and local peasant girls attracted by the exciting interruption of an army into their dull lives) the regiments wives were expected to cook, clean, mend and forage for their husbands and his comrades. An army wife was therefore effectively married to the company, and in the French army Blanchisseuses were expected to perform these services in order to qualify as an official part of the regiment.

Danger

Such a role could be as dangerous as physically taking part in combat as private Wheeler of the 51st foot describes in one of his letters. On the morning of the 28th of October, 1812 the British army was camped near Valladolid after their withdrawal from Burgos and was preparing to blow the bridge. As a consequence the French bought up some guns and fired on the camp. According to Wheeler, the first to be killed was the unfortunate Mrs. Maibee who was preparing breakfast while her husband was on duty at the bridge. While in the act of "taking some chocolate off the fire" she was hit by a roundshot which "carried away her right arm

and breast". [14]

Another unlucky woman died while nursing the wounded at the general hospital at Fuentarrabia. She had been appointed as a nurse to the ward in which her wounded husband was being treated, and caught an infection while removing a bandage from a man with a gangrenous wound, as she had pricked her finger with a needle. The finger and then the hand were removed to stop the infection but neither operation was successful and she soon died. [15]

A Mrs. Reston of the 94th similarly tended the sick, bolstered the defences with sand bags, and braved shell and roundshot to collect water from a well during the defence of Cadiz in 1810. [16]

Other acts of heroism were carried out by the army's women often in the thick of the action, or after a battle in search of their loved ones; even though women were normally expected to stay behind the battle lines. The famous example of Agustina Sanchez "The Maid of Saragossa" (although highly romanticized by later artists and poets) is one which clearly illustrates both patriotism and loyalty to her loved one. Agostina helped crew a cannon after her fiance was killed during the defence of Saragossa, firing a twenty four pounder into an advancing column at ten paces. Her action was decisive and as a result she was granted a subLieutenants commission in the artillery and a substantial life pension. [17]

It was more usual, however, to find women searching the battlefield for missing loved ones. Bourgogne relates how his regiment's Spanish Cantiniere Florencia was wounded while searching for her wounded father (the regiments band master) in the Shevardino redoubt during the 1812 campaign in Russia. [18]

A similar example is that of Rifleman Mauley's Spanish lover who usually followed him into battle mounted on a donkey (on which she carried provisions to sell to the troops) on one occasion he was hit and killed in the Pyranees -- she rushed over to rescue him, but upon finding him dead the distraught woman had to be rescued by a brave Spaniard in British service. [19]

Such acts were by no means confined to the rank and file. Mrs. Dalbiac, for example, (the wife of a cavalry officer) set off after dark on the night of the battle of Salamanca to find her missing husband searching until late in awful surroundings. After finding her wounded cousin Lieutenant Norcliffe and arranging for him to be attended to, she found her husband unharmed. [20] It is therefore probable that there would have been a fair number of women present on the battlefields of the Napoleonic wars who refused to stay safely with the baggage.

The French Army's Vivandieres were much more likely to be seen on the battlefield taking ammunition to the troops or selling them spirits (mostly brandy). One account tells of a Vivandiere distributing liquor and kindly asking for payment "tomorrow" after the battle. Her role was more official than that of the British army wife, and it was ordered that a vivandiere must be well-mannered and moral, devoted to duty and married to an N.C.O. She was also issued with a "patente de Vivandiere" after being enrolled and assigned a registration number by the appropriate Provost. This specified that she must sell only necessary goods at

a fair price and must obey the regulations of the military police. It also contained a personal description of the woman and details of any animals and vehicles she owned.

As John Elting points out; "The Vivandieres badge was her tonnelet, a small keg -- almost always painted red, white and blue -- which she carried slung on a broad shoulder belt [21] in which they always carried something fortifying to sell to the troops. Those who had a tent and transport would set up a canteen (and thus be classed Cantinieres) which became the unit's social centre, like an officers club or cafe. [22]

They were by no means delicate femmes: and were clearly as tough as the soldiers they served. One woman, a vivandiere of the 14th Legere carried her husband on her back for two leagues, while his comrades shot their way out of a Calabrian ambush, while another shot a Cossack out of the saddle and took his horse after the battle of Leipzig. [23] So despite the fact that they could be a hindrance they were a necessary part of the Grand Armee.

Bereavement

Bereavement was an everyday fact of life for the soldier's wife under the hazardous conditions of war, and from the evidence we have, it would seem that re-marriage was very common (for the woman's protection) and there would never be a shortage of suitors within her late husbands company. Burgogne observed that; "during a campaign, if a woman is pretty she is not long without a husband" while Glieg observed that because of the small proportion of women as compared to men on the regimental strength few widows stayed in that state for any unreasonable time." [24]

Wheeler was very philosophical about the plight of the young widows of his regiment and was sorry (or those who were recently bereaved. One of his companions, however, was not so kind in his judgement of the women after a battle; "...Oh Damn it said he, was it, I am sorry for her, but you know there is so many of these damned women running and blubbering about, enquiring after their husbands. Why the devil don't they stop at home where they ought to be". Later in Wheeler's quoted conversation with his cynical friend Wheeler comments about a "snivelling" woman; "She has reason to snivel as you call it", "She is the most unfortunate creature in the army". "unfortunate indeed" said Marshal "Why I think she is devilish lucky in getting husbands, she has had a dozen this campaign". Marshal was, however, exaggerating, but Wheeler tells us that the man the woman had lost had been her third husband. [25]

Bereaved women did not always re-marry, and many probably felt unable to tie the knot again so quickly, despite the problems that being a single woman alone might create. The often quoted example of Mrs. Cockayne, who refused Rifleman Harris' proposal of marriage is a good one. Cockayne was killed next to Harris in battle so consequently Harris was able to confirm to Mrs. Cockayne that her husband was dead and lead her to his body. Together they buried him after performing the service for the dead over him from Mrs. Cockayne's prayer book, she then returned to her husband's company and joined the other bereaved women. Mrs.Cockayne and Harris struck up a good friendship, but the woman refused Harris' proposal saying that, "she had received too great a shock on the occasion of her husbands death ever to think of another soldier." [26] Harris tells us that she succeeded in gaining passage to England when the army reached Lisbon. A Mrs. MacDermot was similarly inconsolable after her husbands death outside Bayonne in 1814 and the whole company raised for her a "handsome subscription" to send her home to

Cork. [27]

Things may have been fractionally easier for local women who followed the army (and our sources do tell us that there were many of them) but they still had to deal with the same hardships even if they were on native turf, while many accounts exist of trouble between the native population and the army as they did not want their daughters to follow the soldiers to war. One gunner subaltern who was billeted with a wealthy Spanish family fell in love with their daughter but as she was the niece of a Spanish bishop there was no possibility of gaining approval for a marriage. Consequently, the Subaltern attempted to get the relatives drunk and escape the next day, with the girl disguised as a postilion. The plan failed and the girl was caught by her aunt. [28]

Some matches on the other hand were acceptable - while in Lisbon, Harris was set to work mending the men's boots in a cobblers shop, and while there he fell in love with the Cobbler's young daughter. The parents approved as long as Harris converted to Catholicism and deserted from the army. Both measures were unacceptable to the rifleman and he left, promising to return after the war and marry the girl, but he comments rather callously that he had soon forgotten her. [29] More successful was the match between Harry Smith and a Spanish girl Juanna who he had rescued after the storming of Badajoz in 1812. She accompanied him through the subsequent campaigns of the Peninsula and eventually returned to England with him after the war. [30]

Finally, it must be noted that officers also often brought their wives along on campaign with them in order to continue the comforts of home, but had to make all their own arrangements to do so. These ladies would have shared in all the dangers of the campaign, but their hardship would have been considerably less because of the commodities money could buy. Many accounts tell of the large quantity of luxuries and baggage an officer would bring to ease the hardships of campaign life, from umbrellas to silver ware, while if billets were available it is unlikely that an officer's family would have been refused them. One captured French diarist described a British officer's family that he saw at Elvas thus;

"The captain rode first on a very fine horse, warding off the sun with a parasol: then came his wife, very prettily dressed, with a small straw hat, riding on a mule and carrying not only a parasol but a little black and tan dog on her knee, while she led by a cord a she-goat, to supply her with milk. Beside Madame walked her Irish nurse, carrying in a green silk wrapper a baby, the hope of the family. A grenadier, the Captain's servant, came behind and occasionally poked up the long-eared steed of his mistress with a staff. Last in procession came a donkey loaded with much miscellaneous baggage, which included a tea kettle and a cage of canaries; it was guarded by an English servant in livery, mounted on a sturdy cob and carrying a long posting-whip, with which he occasionally made the donkey mend its pace." [31]

Life was, therefore, somewhat easier for the officer's wife, and some semblance of their genteel life style would have continued under the canvas of a military camp. Makeshift dinner parties took place, while sumptuous balls were often held by the British army's

Spanish and Portuguese allies in the Peninsula.

Spain was a rough country, and for many officers the comforts of feminine company would have seemed a necessity. The French Marshall Messena, for example, took a captain's wife with him on campaign as his mistress. She was attractive and quick

witted but was unacceptable to several of Messena's fellow officers. She dressed and rode like a dragoon but lacked stamina and slowed the Marshall down in both advance and retreat. [32] Keeping a mistress was by no means unique in the army, and many examples could be cited (for example there was a woman mistress to a captain of the

Scots Brigade who was killed at Vittoria). [33]

Under the pressures of war, therefore, official regulations were often flouted and a good deal of informality took place. Huge hordes of unmarried women would have followed the troops (many as loyal to their men as those "married before God") while examples do exist of couples trying to obtain an official marriage in order to gain privileges within the army. When the French third company of sailors left the siege of Cadiz for France it was stated that only those women who were married could accompany their men. A surprising number of the Spanish women could prove that they were married, while several who were not, followed the French columns back to Paris on foot. [34]

Contemporary View

Lastly it only remains to make a few observations about how these women were viewed at the time. It is easy now to over

romanticize these women, either by looking at them as over strong Bernard Cornwall style characters, or in a "Jane Austen" vain, even though many love affairs did take place leading to broken hearts, happy endings, and in two example we have cold blooded murder [35] (I have tried to steer clear of this aspect of the lives of Napoleonic women and I refer you to Brigadier F.C.Q. Pages excellent book, especially chapter seven for the romantic involvements of both officers and men). These women were undoubtedly rough and there were examples of women fighting in i the ranks as men, and acting as spies, but it must be remembered that at the time women were largely seen as inferior to men and it was believed that they were incapable of performing many of the tasks which men undertook. We must therefore be careful not to look for the present in the past when viewing these women (Napoleon, for example regarded women as "mere machines" to make children [36] ). To a certain extent, therefore, they wouldn't have acted or been treated in the way that women are today.

Our last word must therefore go to Lady Priscilla Burghresh, who described Austrian Sutleress' (who were a semi official appointment uniformed in a version of the outfit their regiment wore) thus; "I wish you could see the women who follow the armies, particularly the Hungarians; there is no doing justice to the horror of these monsters; they wear boots and other articles of dress exactly like the men and ride on men's saddles." [37]

The Nineteenth Centuries view of good womanly conduct is, therefore, clearly very different from ours! These women were uncouth and tough by the standards of the day, probably very dirty and poorly dressed and were brutal, pillaging and looting the dead in order to survive. They were as much veterans of the wars as the soldiers they followed and in a world where fighting battles made up only a small amount of a soldiers experience, camp life and camp followers were a vital part of an army.

J.R. Elting, Swords Around a Throne, Napoleon's Grande Armee, Wiedenfeld and Nicolson, (1988)

[1] This Irish lament, which became "When Johnny comes marching home again" during the American War of Independence, is as much a song about the effects of war on a soldiers wife as of the terrible injuries a soldier of the period could sustain which could leave him a crippled beggar

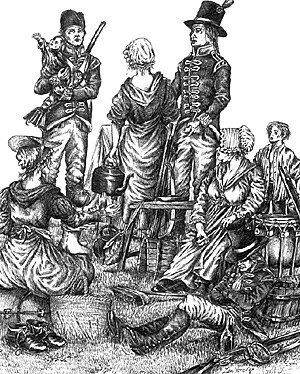

While on campaign, in addition to the soldiers, staff, supply train and other authorised military services, a huge number of persons -- both authorised and unauthorised -- would have followed the baggage train of an army, the bulk of whom were women. From the officer's wife or mistress to the local peasant girl, women were necessary to the army in a world where soldiers received only the most rudimentary of comforts. Camp followers were, therefore, necessary for maintaining both comfort and morale, while at the same time an army on the move was an exciting attraction for many women. [1]

While on campaign, in addition to the soldiers, staff, supply train and other authorised military services, a huge number of persons -- both authorised and unauthorised -- would have followed the baggage train of an army, the bulk of whom were women. From the officer's wife or mistress to the local peasant girl, women were necessary to the army in a world where soldiers received only the most rudimentary of comforts. Camp followers were, therefore, necessary for maintaining both comfort and morale, while at the same time an army on the move was an exciting attraction for many women. [1]

"it is essential to limit the number of women allowed to follow the army, they are in such great number that they hinder the march of the troops, consume large quantities (of food) and occupy a great number of wagons intended exclusively for the transportation of baggage and supplies.... The great horde of women who follow the armies is frightful."

Some women, however, could not be stopped from following their men to war. In 1799 for example, while watching troops embarking for

Holland at Margate, Lady Bessborough observed an unhappy "not-to go", girl fling her child into the arms of her husband, and then leap after it herself onto the moving ship to the cheers of the watching crowd. The soldiers on deck naturally made room for her.

[5]

Some women, however, could not be stopped from following their men to war. In 1799 for example, while watching troops embarking for

Holland at Margate, Lady Bessborough observed an unhappy "not-to go", girl fling her child into the arms of her husband, and then leap after it herself onto the moving ship to the cheers of the watching crowd. The soldiers on deck naturally made room for her.

[5]

The retreats to Vigo and Corunna have left us many accounts of the awful conditions that both women and men underwent while on campaign. Sir John Moore's army was forced back from his advance into Spain by a French army of 80,000 between December 1808 and February 1809 in what could be seen as the "Dunkirk" of the Peninsula war. Those involved in the retreat faced terrible weather conditions and gruelling marching with little opportunity for rest or food and many anecdotes have come to us of the courage and endurance of the armies women. Benjamin Harris of the 95th tells of a mother dragging along an exhausted child of seven

or eight years of age who's legs were "failing under him".

The retreats to Vigo and Corunna have left us many accounts of the awful conditions that both women and men underwent while on campaign. Sir John Moore's army was forced back from his advance into Spain by a French army of 80,000 between December 1808 and February 1809 in what could be seen as the "Dunkirk" of the Peninsula war. Those involved in the retreat faced terrible weather conditions and gruelling marching with little opportunity for rest or food and many anecdotes have come to us of the courage and endurance of the armies women. Benjamin Harris of the 95th tells of a mother dragging along an exhausted child of seven

or eight years of age who's legs were "failing under him".

They were troublesome, and the only real way of controlling them was to announce in the orders of the day that the troops were free to loot any vivandiere found outside their designated place, and without their necessary badges. Naturally they were looters themselves and fences for stolen goods but despite their vices they were expert foragers and shared in all the hardships of the men.

They were troublesome, and the only real way of controlling them was to announce in the orders of the day that the troops were free to loot any vivandiere found outside their designated place, and without their necessary badges. Naturally they were looters themselves and fences for stolen goods but despite their vices they were expert foragers and shared in all the hardships of the men. Bibliography

B. Fosten, Wellington's Infantry 1, Osprey Men-AtArms Series 114, (1981)

E. Hathaway, ed.,A Dorset Rifleman, The Recollections of Benjamin Harris, Shingelpicker, (1996)

P.J. Haythornthwaite, The Napoleonic Source Book, Arms and Armour Press, (199 1)

P.J Haythornthwaite, Austrian Armies of the Napoleonic Wars 2; Cavalry, Osprey Men-At-Arms Series 181, (1986)

P.J. Haythornthwaite, Napoleon's Line Infantry, Osprey Men-AtArms Series, 141, (1983)

N. Leonard, Wellington's Army Recreated in Colour Photographs, windrow and Greene, (1995)

B.H. Liddell Hart ed,. The Letters of private Wheeler 1809-1828, The Windrush Press, (1993)

Brigadier F.C.G. Page, Following the Drum, Women in Wellington's Wars, Andre Deutsch, (1986)

A. Stiles, France, Napoleon and Europe, Hodder and Staughton, (1988)

M. Windrow, Military Dress of the Peninsula War, 1808-1814, Windrow and Greene, (1974)

Footnotes

[2] J.R. Elting, Swords around a throne, p.607

[3] F.C.G. Page, Following the Drum, F. 17

[4] F.C.G. Page, Following the drum, p. 19

[5] F.C.G. Page, Ibid., pl.

[6] J.R. Elting, Swords Around a Throne, p.607

[7] F.C.G. Page. Op. Cit., p.31

[8] F.C.G. Page, Op. Cit., P.27

[9] F.C.G.Page, Ibid., p.36, The convent was devastated by the British troops, and taken up by braying mules, muleteers and drunken soldiers.

[10] E. Hathaway,ed, A Dorset Rifleman, p. 110

[11] E. Hathaway, Ibid., P. 107

[12] E. Hathway, Ibid., p. 118

[13] F.C.G. Page, Op.Cit., P. 102

[14] B.H. Liddell Hart, edThe Letters of private Wheeler 1809-1828, p. 100.

[15] F.C.G. Page, Op. Cit., p. 107

[16] F.C.G. Page, lbid.,P.57

[17] P.J. Haythornthwaite, ed. The Napoleonic source book, p.295, F.C.G. Page, Op. Cit., p.59

[18] P.J. Haythornthwaite, Napoleons Line Infantry, (Osprey Men-atArms 141), p.33

[19] F.C.G. Page, Op. Cit., p.53

[20] F.C.G. Page, Ibid., p.56

[21] J.R. Elting, Op. Cit., p.612

[22] J.R. Elting, Ibid., p.615

[23] J.R. Elting, Op. Cit. P.610/ p.605

[24] F.C.G. Page, Op. Cit., p.49/50

[25] B.H. Liddell Hart, ed, The Letters of private Wheeler, p. 141

[26] E. Hathaway, ed, op. Cit., p.47

[27] F.C.G. Page, Op. Cit., p.54

[28] F.C.G. Page, Ibid., p.80

[29] E. Hathaway,ed, Op. Cit., p.75

[30] F.C.G. Page, Op. Cit., p.88

[31] B. H. Liddell Hart, ed, Op. Cit., p. 101

[32] J.R. Elting, Op. Cit., p.611

[33] F.C.G. Page, Op. Cit., p.50

[34] J.R. Elting, Op. Cit., p.611

[35] See F.C.G. Page, Op. Cit., pp. 60 and 85

[36] A. Stiles, Franc Napoleon and Europe, p.89

[37] P.J. Haythornthwaite, Austrian Armies of the Napoleonic Wars 2; Cavalry, p.47

Back to Age of Napoleon 27 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1998 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com