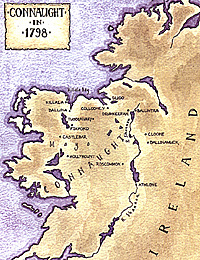

Connaught 1798 Large Map (slow: 179K) There is a definitive distinction between invasion and conquest for, although Britain was not conquered by an overseas (i.e. outside the British Isles) power again, the instances of invasion, both threat and actual, were numerous. The periods when invasion from overseas threatened were sporadic and of differing extremes. They ranged from cross channel raiding and the burning of coastal towns during the Hundred Years War to that of the threat of invasion and possible conquest during the Napoleonic Wars and again during the Second World War. Although the greatest risk was posed by France (until Germany took its place during the twentieth century), by no means was France the only aggressor.

For instance, during the sixteenth century, invasion threatened on two separate occasions. During the 1530s and 40s, at the behest of the Pope, the Catholic monarchs, Francis I of France and Charles V of Spain, combined against Henry VIII over his divorce from Catherine of Aragon and his assumption of supremacy over the church. One result of this was Henry VIII's national defence policy.

[1]

The next crisis was that between Elizabeth I and Phillip II of Spain which culminated in the Spanish Armada of 1588. Eighty years later the Dutch posed a threat which culminated in the naval attack on the River Medway in 1667. In 1797, the Dutch, this time allies of France, threatened again, made the more serious as elements of the Royal Navy were in a state of mutiny. The invasion fleet was subsequently defeated by Admiral Duncan at the Battle of Camperdown. [2]

Spain posed a danger during the first part of the eighteenth century when war was declared by Britain in 17 18. Early in 1719, two separate invasionneets sailed from Spain and although the main force was dispersed by a storm, the secondary force landed in Scotland. The supporting Jacobite rising as crushed and the Spanish force was defeated at Glenshiel in the Highlands.

As an indirect result of the Hanoverian succession and a desire to alter the balance of power in he Baltic, both Sweden and Russia were receptive to Jacobitism and negotiations to provide military assistance including invasion, were entered into. Ultimately however, both were to prove futile.

Invasion was not always by a foreign aggresor as-there were a number of occasions when a landing was led by a claimant to the throne of England (or Britain). Examples of this are Henry Tudor in 1485, James, Duke of Monmouth in 1685 nd William of Orange in 1688.

However, by far the greatest threat was posed by France. The Jacobites looked upon Franc as its chief supporter (although France was no always receptive to these overtures). It has Ion been debated for what purpose France supported Jacobitism. Did France really wish to see a restora tion of the Stuarts or was the toppling of th Hanoverian regime the key factor ? Alternatively was Jacobitism merely thought to be a side show, way to divert British attention away from continental conflict and so ease the pressure on French armies ? Regardless of the reasoning, between 1692 and the outbreak of the French Revolution, there were no less than ten [3] separate invasion plans, sailings or actual landings. The reasons for the lack of sucess of these designs are numerous although the role of the Royal Navy during this period was decisive and was to remain so.

Coastal defence was vital to the security of Britain but the various schemes applied after the defence policy of Henry VIII were largely ad hoc and usually reactive (for example, the improvement in the Medway and Thames defences following the Dutch attack in 1667). [4] Defences were constructed primarily to protect Britain's ports, guarding the estuaries of major rivers and protecting the south eastern coastline of England, the area of coast closest to France.

This, and the dominance of the Royal Navy, meant that the would be invader would have to look to more remote landing areas and would have to make lengthy detours to avoid the Navy. So when Britain was again at war with France during what became known as the Napoleonic Wars, the French were forced to look towards Ireland to find suitable landing areas. Although Ireland had a remote enough coastline for invasion purposes, the primary interest for France was that Ireland was considered ripe for rebellion.

18th Century Ireland

Eighteenth century Ireland was more of a colony than a part of Britain. The century saw the incomes of the (frequently absentee) Protestant landlord class treble whilst the conditions of the indigenous Catholic peasantry worsened. The Irish economy was disadvantaged for English gain (for example, since 1698 Irish wool and cloth could not be exported to anywhere save England) and the Catholic majority was legally disabled. The colonial image was further enhanced by the fact that Ireland was the largest concentration of the peace time British Army. [5]

Tone, founder of the French Revolution inspired United Irishmen, had been expelled from Ireland in 1795 and was the energy behind subsequent French attempts upon Ireland. As an adjutant general in the French Army his enthusiasm led to the 1796 invasion attempt. On 16 December that year, 35 ships, with 12,000 troops on board, sailed from Brest and, slipping past the British blockade, they arrived off Bantry Bay (South West Ireland) on 21 December. A change in the weather conditions prevented a landing and the worsening conditions forced the abandonment of the invasion. As Tone put it " England had not had such an escape since the Armada." [7]

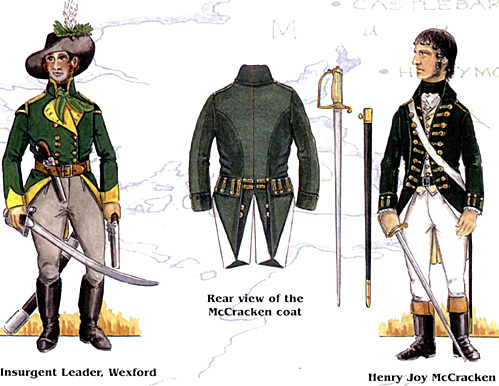

Despite this setback, the United Irishmen continued to plan for rebellion, gathering arms and intimidating landlords and magistrates. Meanwhile, the French were forming an army in northern France with the intention of invading England. Early in 1798, however, the government, benefiting from treachery as well as efficient intelligence, struck a sudden blow, imposing martial law and arresting the patriot leaders. This resulted in a premature outbreak of the rebellion in May. Despite early successes, the insurgents were ill equipped, ill disciplined and generally leaderless and regardless of their valour, the best they could hope for was to hold out against heavy odds until foreign help arrived. Throughout the early summer rebellion broke out in Counties Dublin, Kildare and Wexford, and lastly in Down and Antrim.

Tone, meanwhile, was in Paris seeking French aid, urging that the Armee d' Angleterre be used for an invasion of Ireland.

[8] However, Napoleon was intent on conquering Egypt, considering invasion of England to be "the most daring and difficult task ever undertaken" [9] and French intervention in Ireland was not a priority.

As long ago as April, Tone had discovered that Napoleon had departed for Egypt and had taken the Armee d' Angleterre with him. [10] News of the rebellion altered the situation and in July General Jean Humbert was ordered to La Rochelle to take command of an expedition of more than a thousand men. General Hardy was ordered to Brest to command a further 3,000, and General Kilmaine was ordered to follow Humbert and Hardy, who were to sail simultaneously, with 8,000 troops.

Humbert finally sailed on 6 August in three frigates which, in addition to the troops, carried three thousand muskets, 50,000 Francs and one thousand French uniforms with which to equip the first Irishmen who volunteered.

[11] The small fleet sailed a circuitous course in order to avoid the Royal Navy and finally landed at Killala, County Mayo (north west Ireland) on 23 August.

Mayo was amongst the most destitute of the Irish counties and support for the French was strong. Although well equipped, Humbert's one hundred cavalry and his artillery had no horses [12] and one of his first objectives was to rectify this. This was achieved and by 25 August the French, together with their Irish allies, had scattered the yeomanry who blocked their way, first at Killala and then at Ballina.

News of the invasion spread quickly. The British Viceroy, Marquis Cornwallis, who had in the region of 56,000 [13] British regulars, yeomanry and militia to call upon, gathered his forces and began a slow advance to meet the invasion. He sent General Lake (who had earned a notorious reputation for the brutal methods he employed in putting down the rebellion in Wexford) to Castlebar to take command of the garrison which now stood in Humbert's way.

Humbert, after garrisoning Killala and Ballina, undertook an overnight march on Castlebar, moving cross-country to keep the element of surprise on his side and on the morning of 27 August, he attacked. After garrisoning Foxford, Lake had 1,610 troops

[14] drawn up to face 800 French and approximately 600 Irish. [15] The opening moves of the battle went the way of the British, their artillery causing much carnage within the Franco-Irish ranks. Then, a French charge broke through the British ranks who, in turn, broke and fled in all directions, some not stopping, save to plunder some of the local inhabitants, until they reached Athlone, some 60 miles distant.

The Races of Castlebar, as the defeat and flight of the British became known, was a great morale boost to the Franco-Irish Army. The British abandoned their garrisons in the area which meant that Humbert was now the master of most of Mayo.

Cornwallis, meanwhile, was making slow and methodical progress north-westwards and would not be in a position to threaten Humbert for a number of days yet. Would Humbert move out to meet him or continue his campaign of rapid movement and slip past Cornwallis? Humbert instead decided to remain in Castlebar and consolidate his position.

Volunteers

Volunteers continued to join the Franco-Irish army, indeed Humber wrote "I hope within three days to have a corps of two to three thousand of the inhabitants. As soon as the corps of United Irishmen which I am organising shall be clothed, I shall march against the enemy in the direction or Roscommon." [16]

These volunteers were equipped with French weapons, and when these were exhausted, volunteers were issued with pikes, the classic weapon of the insurgents. They were organised into battalions and regiments under the (sometimes nominal) command of those members of the local Catholic gentry who had joined the rebellion.

Connacht was declared a Republic and John Moore, a member of a prominent local family, was named President and a committee was formed to help him govern.

It is surprising when the actions of the British are considered, that the Irish did not retaliate in kind (as insurgents elsewhere had done) and it is to the credit of the insurgents that the Protestant residents of Mayo-were able to remain largely unmolested.

All the time that the Franco-Irish remained in Castlebar, Cornwallis drew nearer, tightening the net. Humbert was awaiting the arrival of Hardy's force and had requested further reinforcements. However, unknown to Humbert, on 26 August the Directory had ordered Hardy to postpone his enterprise until the equinoctial gales broke the British blockade.

The United Irish agents in France had briefed Humbert that once he landed, the population would

rise up and join the French to rid Ireland of the British. The Directory had even instructed Humbert to do everything to encourage the "hatred of the English name." [17] Those who did join him, with a few notable exceptions, were from peasant stock, hardly the material from which to form chains of command or provisional government.

The drilling of the volunteers presented its own problems. Recruits jammed muskets as cartridges were mis-loaded and once they managed to load their weapons, many wasted both powder and shot by firing upon local ravens who were prized for their quills.

[18]

Even less familiar to the recruits were French rations. To a population brought up on a diet of sour milk and potatoes, meat was an extremely rare luxury. However, the recruits were quick to develop a taste for it, eating more, proportionately in four days than the Armee d' Italie (which many of Humbert's men were veterans of) would consume in a month. [19]

An inhabitant of Castlebar noted: "The musquets were pronounced, by those who were judges of them, to be well fabricated, though their bore was too small to admit English bullets. The uncombed ragged peasant, who had never before known the luxury of shoes and stock ings, now washed, powdered, and full dressed, was metamorphosed into another being." [20]

The longer that Humbert waited in Castlebar the closer Cornwallis moved. But this was not Humbert's only problem. If English reports are reliable, then the French were growing restless, showing signs of strain and even of mutiny. [21] Relationships between the French and Irish were also straining, for the French had expected to see the whole country rising in support. The Irish, on the other hand, had expected greater numbers of French to land than actually did. As General Jean Sarrazin, one of Humbert's Officers, described during the march on Castlebar

"Along the way we met crowds of people of the countryside. Their joy changed into sadness when they saw the fewness of our numbers. Tears were seen flowing from their eyes, showing a real affection - we could have thought that they were assisting at our funerall." [22]

The British government reacted swiftly when news of the disaster at Castlebar reached them. Although Prime Minster Pitt was awaiting news of Nelson's confrontation with Napoleon off Egypt, he was still able to dispatch reinforcements to Ireland within hours of receiving the news. Meanwhile, Cornwallis was moving ever closer and on 4 September he reached Hollymount, just 13 miles from Castlebar. The next day he would move on Castlebar itself.

Cornwallis was, however, thwarted in this attempt to catch the Franco-Irish in the town. Realising that he was unlikely to gain the required reinforcements whilst he was in Castlebar and not wishing to be trapped in the town, Humbert

marched northwards towards Sligo whilst Cornwallis approached Castlebar from the south.

Humbert brushed aside a small force sent from Sligo to block his path at Tubbercurry and was there joined by a body of insurgents from Ballina. Just before noon on 5 September Humbert reached Collooney, just ten miles south of Sligo. There he was attacked by the Sligo garrison under Colonel Vereker.

Through their artillery, the British gained the initial advantage, and musketry, too, was taking a toll on the Franco-Irish. Then one of those instances of individual courage which appear to fill the pages of the annals of warfare occurred. Bartholomew Teeling, an Irish officer serving with the French, rode out of the Franco-Irish ranks and galloped towards the British artillery. Singling out the gun which was causing particular damage, he calmly pistolled the gunner dead and then returned to his own ranks. [23] (Teeling was later executed by the British for his part in the uprising). The silencing of the gun was a turning point of the engagement as the Franco-Irish were now able to continue their advance upon the British. Fearing that he was about to be surrounded, Vereker ordered the retreat, but instead of retiring in good order, his forces panicked and fled.

At this point, Cornwallis altered his plans. Despite the advice of his officers to continue the pursuit of Humbert towards the north (although it was also suggested that Humbert may attempt to double back and re-enter Mayo), Cornwallis felt that

Humbert would, sooner or later, strike southwards and so he divided his army accordingly. The first corps, under General Lake, was to trail Humbert whilst the second, under Cornwallis himself, would keep itself between the Franco-Irish and Dublin.

[1] Saunders, A. Fortress Britain - Artillery Fortification in the British Isles and Ireland (Liphook, Beaufort Publishing Limited, 1989) p 36.

It is a commonly held perception that the last invasion of Britain took place in 1066. This invasion represented the beginning of the Norman Conquest of England. Ireland, Scotland and Wales were not subjugated until much later, and not always by military means. In fact, some would argue if they were ever fully conquered.

It is a commonly held perception that the last invasion of Britain took place in 1066. This invasion represented the beginning of the Norman Conquest of England. Ireland, Scotland and Wales were not subjugated until much later, and not always by military means. In fact, some would argue if they were ever fully conquered.

Under these circumstances, it was no surprise that Theobald Wolfe Tone, a Dublin barrister stated "Ireland (was) an oppressed, insulted, and plundered nation. As we well knew what it was to be enslaved, we sympathised most sincerely with the French people; we had not, like England, a prejudice rooted in our very nature against France. As the Revolution advanced, and as events expanded themselves, the public spirit of Ireland rose with a rapid acceleration." [6]

Under these circumstances, it was no surprise that Theobald Wolfe Tone, a Dublin barrister stated "Ireland (was) an oppressed, insulted, and plundered nation. As we well knew what it was to be enslaved, we sympathised most sincerely with the French people; we had not, like England, a prejudice rooted in our very nature against France. As the Revolution advanced, and as events expanded themselves, the public spirit of Ireland rose with a rapid acceleration." [6]

By July the rebellion had largely been crushed, save for Wexford where the insurgents were still holding out. However, not all of Ireland had risen. Many areas were awaiting the news of a French landing before rising, whilst in other areas, such as Down and Antrim, the embers of rebellion could yet be rekindled.

By July the rebellion had largely been crushed, save for Wexford where the insurgents were still holding out. However, not all of Ireland had risen. Many areas were awaiting the news of a French landing before rising, whilst in other areas, such as Down and Antrim, the embers of rebellion could yet be rekindled.

References

[2] Reilly, R. William Pitt the Younger (New York, G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1979) pp 336-7.

[3] Szechi, D. The Jacobites - Britain and Europe, 1688-1788 (Manchester, Manchester University Press, 1994) pp xii-xxv.

[4] Saunders, Op Cit. pp 94-5.

[5] Porter, R. English Society in the Eighteenth Century p 49 taken from Boyce, D.G. & O'Day, A. (Editors) The Making o

Modern Irish History (London, Routledge, 1996) p 15.

[6] Tone, T. Wolfe The Autobiography of Theobald Wolfe Tone edited by O'Brien, R. B. taken from Finn, J. & Lynch, M. Ireland and England, 1798 - 1922 (London, Hodder and Stoughton, 1995) p 11.

[7] Tone, T. Wolfe Journal for December 21 st 22nd taken from Pakenham, T. The Year of Liberty (London, Granada Publishing Ltd., 1912) p 23.

[8] Greaves, C. D. Theobald Wolfe Tone and the Irish Nation (Dublin, Connolly Publications Ltd., 1989) p55.

[9] Glover, M. Warfare in the Age of Bonaparte (London, Cassell Ltd., 1980) p61.

[10] Greaves, Op Cit. p 55.

[11] Hayes, R. The Last Invasion of Ireland (Dublin, Gill and Macmillan Ltd., 1979) p 10.

[12] Hayes, Op Cit. p 24.

[13] Pakenham, T. The Year of Liberty (London, Granada Publishing Ltd., 1972) p 52.

[14] McAnally, Sir H. 'The French invasion of Connacht, 1798: some problems in numbers', Bulletin of the Irish Committee of Historical Sciences (37) (1945) p 2.

[15] Sarrazin, General J 'Notes sur l'Expedition d'Irlande', appeared as Hayes, R. 'An Officer's Account of the French Campaign in Ireland in 1798', Irish Sword (2) (1955) p114.

[16] Humbert, General J. taken from Hayes, R. The Last Invasion of Ireland (Dublin, Gill and Macmillan Ltd., 1979) pp 57-8.

[17] Stock, J. Narrative of What Passed at Killala during the French Invasion of 1798 (1800) pp 1-2 taken from Pakenham, T. The Year of Liberty (London, Granada Publishing Ltd., 1972) p 348.

[18] Ibid., pp 31-2 taken from Pakenham, T. The Year of Liberty (London, Granada Publishing Ltd., 1972) pp 360-1.

[19] Pakenham, Op Cit. p 350.

[20] roiley, T. (Editor) Eyewitness to 1798 (Cork, Mercier Press,

1996) pp 78-9.

[21] Hayes, Op Cit. p 70.

[22]Sarrazin, Op Cit. p 114.

[23]Hayes, Op Cit. p 93.

Back to Age of Napoleon 27 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1998 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com