Q.23.3: Position of Flags in Austrian Infantry Formations:

A. From 1748 to 1808, Austrian Line battalions carried two flags. From 1808, this was reduced to just one, a Leibfahne for the 1st and an Ordinarfahne for the others. I presume from the references to 'flag' and Bowden & Tarbox that the question relates to 1809, so the relevant regulation is the 1807 Exercierreglement, (although the previous 1769 regulations were not much different). At this time, the standard was carried by a FQhrer, who was a senior NCO, who was officially part of the regimental staff.

Part 1, Chapter 2, Section 3 of the 1807 Regulation covers: Position and Movement of the FUhrer with the Flag: When the troops are standing with arms shouldered, the position of the FOhrer, both in and ahead of the front line either at the halt and on the marc~ is as follows: When the weather is good and the winds light, the flag is left to fly; but in strong wind however, either the lowest corner of the flag is held to the pole by the left hand or the flag is rolled halfway on to the pole. On the march or during drill, the cover can be placed over it, but when marching out on parade, the flag must be fully extended without regard to the weather.(The Ehrenbande ribbons were only attached on parades). (At the halt) The flag is located in the centre of the front rank, between two Unterleutnants in the first two battalions and two Oberleutnants in the third. (see diagram 1 Plate 1 of the '74 Plates Attached to the 1807 Exercier Regulations').

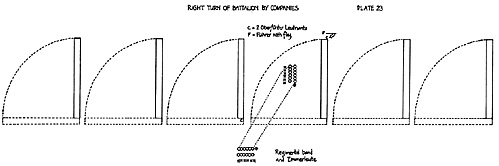

In a march to the front, the flag is located six paces ahead of the front. When the line breaks up into subunits to the front or rear, the flag always moves in line with the turning flank of the nearest subunit to its left or right, and when marching in column and deploying into line, it always remains there. (see diagram 2: Plate 23 of the '74 Plates Attached to the 1807 Exercier Regulations). When the guards form up in the field or in the garrison, the flag is located three paces in front of the gap between the first and second file of the right wing. At the cautionary order for marching off, the FUhrer moves to a position in front of the first subunit and marches at this distance in front of the front line during the advance and withdrawal. On the march, the flag can be carried in a comfortable position.

Chapter 3 Section 1: Firing at the Halt provides that when the drums beat to start the firing procedure, the flag moves back to the third rank. Part 1, Chapter 7, Section 2 confirms the flag's position when marching to the front, six paces out ahead of the centre of the front of the battalion.

This could be a risky business, as related in Branko: Geschichte des kk Infanterieregimentes IR44 (1875): Advancing south of Essling village on 21st May 1809, "Hauptmann Giletta with the 1st Battalion had just beaten off an enemy attack, when in the course of advancing into deep corn, it suddenly ran into enemy troops concealed by the darkness.

The infantry, formed in Mass, received a volley from these troops at close range, as a result of which the colour party were felled. Leutnants Lehmann and Gallina were wounded and the FQhrer killed. Disorder spread throughout the Mass at that moment, so that the loss of the flag was only noticed when Hauptmann Giletta reformed the battalion again in its old position. Fortunately, it had already been recovered by elements from the 2nd Battalion sent in support and was returned when Giletta was setting about preparing to recover the flag."

The flag did not have any guiding function, although it served as a reference point both for the senior commanders and troops in the battalion. The battalion adjutant would designate the point the flag party was to head for, before the troops moved off. Thereafter, on the march "the Battalion Adjutants (marched) behind the middle of their battalion along the intended line of march, so as to keep the flag and target point constantly in view". One battalion would be leading the march and so the adjutants and colour parties of other units would follow the flag of the 'Directions- Bataillon' to maintain the proper alignment.

The process of advance and fire laid out in Part 1, Chapter 8, Section 1 was drilled by an advance of 100 paces at the double. It was acknowledged that this distance would depend on circumstances. Once the line halted, the flag party would move to the rear and return to lead the next advance at the usual six paces. Once the advance ended, the flag would return to its position in the front rank, as at the halt.

Part 2 of the 1807 Regulations covers columns and Masses (closed columns). Its introduction states that columns were used for manoeuvring large units of troops, especially when terrain prevented a march deployed on a battalion front. These columns were usually formed up to march off on company or smaller frontages, but there is nothing specific about where the flag was located. It would appear that on a march, the flag would be six paces out ahead at the front, but once on the battlefield, the regulations presume an initial deployment into line, when the flag would move to its central position.

Generally, its location would depend on how the battalion changed formation. For example, if forming column from line as per diagram 2, it would finish up halfway back on the left side of the third company, but if the line changed to a double company column on the centre, the flag would remain in the centre betweeen the 3rd and 4th companies, moving six paces ahead as the column moved off. Because of the compact nature of a column, it was usually sufficient to maintain alignment through the battalion officers (adjutants moving to mark the new line to be taken on a turn), as would be the case for columns smaller than a battalion without a flag.

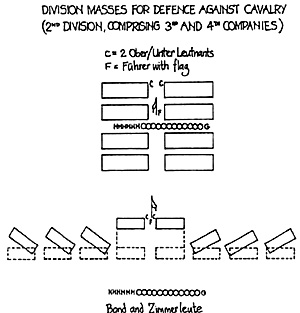

When forming into square, Part 3, Chapter 4, s.1 specifies that once the square is formed up, the officer commanding orders 'Halt'and the flag, but not its accompanying officers moves into the centre. Similarly in that section, when division Masses are formed,from line, the central companies (3rd and 4th) would retain the flag and as it formed up (see diagram 3: Plate 64 of '74 Plates Attached to the 1807 Exercier Regulations'), the flag would move to the inner flank of the second right hand-Zug, (ie: just in front of the centre of the Mass). The presumption in the regulations is always that masses are formed from line, but division masses often and battalion masses always formed up as closed up columns. This is covered in Part 2, Chapter 2, which makes no reference to movement of the flag from its position in the column. Thus it would stay in that position when the Mass was moving, see for example Plate 20, Fig. 2 (reproduced in Rothenberg: Napoleon's Great Adversary). However, when halted, it appears to have been intended that it moved to the centre to clear the first four ranks for firing drill on any face, but the realities of the battlefield suggest it may have remained in the front rank of the front or side, (the inner Zugs being turned out and the rear ones turned about when halted in Mass).

As in other armies, the flag's primary function was to serve as a rallying point for the battalion and it had no directing function, (Part 3, Chapter 3, s.2). There are of course many incidents of flags being seized in order to rally wavering troops or lead a charge, the former most famously by Archduke Charles at Aspern, albeit that episode has been greatly romanticised.

The Grenzer and Landwehr regulations were the same as for the Line, except that the more elaborate evolutions were left out and there was more emphasis on light tactics/sharpshooting for the Grenzers. From the time of their formation in 1808, the regular Jdger battalions did not carry flags.

The only good books on the army and its drill in English are: Rothenburg 'Napoleon's Great Adversary'(rep. 1995) and Nafziger 'Imperial Bayonets' (11996), which is particularly good for the many original diagrams drawn from the relevant regulations. Unfortunately, there is a slight error in Nafziger's speed calculations for the Geschwindschritt, as he calculated the 105 paces per minute as equating to 218 feet per minute instead of 263' feet per minute, so all the speed calculations at thatpace should be reduced by 16.5%.

Apart from these two, and Jack Gill, material coming from the USA about the Imperial Army should be treated with great caution, as the authors have read little or nothing of the key texts and regulations. I would differ with Dr. Esdaile in AoN23 'The Sharp End Revisited', as Nosworthy repeats too much material drawn from French sources. It is also vital to understand what the troops were trained and therefore capable of doing before discussing what happened in battle. Bowden and Tarbox made some use of bits from Vol. 1 of Kreig 1809, but too much of their material seems to be misunderstandings of Rothenberg the origin of the reference to a kind of ordre mixte is unknown!

Their claim that the Division mass was rarely used is nonsense as, following heavy casualties from artillery against Battalion Masses at Aspern, on 5th June, Charles decreed that various measures could be taken to reduce the effect of artillery, one used at Wagram being Division Masses.

As if the above item was not enough information, Dave Hollins has let us have some questions he has received as the author of Osprey MAA299 'Austrian Auxiliary Troops 1792-1816'. These expand on the information he has already given, but for which there was no room in the Osprey:

Mr. F. Vleeschouwer of Schilde, Belgium, asked:

A) Are the uniforms of the Primatial volunteer and Neutra Komitat Insurrection Hussars of 1809 as described at the bottom of p.38 (the 1809 Insurrection uniform of dark blue)? What colour(s) was/were their shakos?

ANSWER:

Although I tried to have each section stand alone as an individual reference, that wasn't entirely possible and so, I have tried to highlight the threads that appear to run through the period.

The Insurrection is poorly documented and they were at the end of a long line of priorities. However, as the officers were all affluent nobles (the Insurrection mirrored the backward feudal society of Hungary), they would have had good quality uniforms and equipment. The regulations provided for the 1809 Hussar uniform at the bottom of p.38 with officers and NCOs using the same distinctions as Line Hussars.

Not to be confused with the regular 12th Palatinal Hussars, (whose Inhaber was Archduke Joseph, Palatine or Viceroy of Hungary), the volunteer Primatial Hussars were raised by Archbishop Primate of Hungary Archduke Charles Ambrosius, who was also Bishop of Gran. As per the 1797/1800 table on p.37, both that area and Neutra were 'Above the Danube'and so wore black shakos. Having been raised from volunteers, the Primatial would have had smart new uniforms, although volunteers drawn from the Gran area Insurrection already had a dark blue uniform.

However, it is quite possible that many of the Neutra Insurrection troopers would have not yet been kitted out with the new uniforms and would have still been wearing the old lighter blue uniform, although the officers would have provided their own new uniforms as per regulations.

B) The text says that the uniforms of the Moravian (like the Bohemian) Landwehr of 1809) imitated the Lower Austrian Landwehr, who are shown on Plate G3 with long grey coats. In other publications, including Osprey MenAt- Arms 176 (Austrian Infantry), it always says a brown Oberrock (long greatcoat). Which colour(s) did the Moravian battalions at Wagram wear?

ANSWER:

The Landwehr is often confused by authors concerning both its structure and uniforms. The whole establishment was officially designated 'Landwehr' as the force to guard their home districts. The Volunteers (Freiwillige) differed because they volunteered to fight alongside the field army. However, they were often referred to as Landwehr and all their ranks were prefixed with Landwehr. As an example, the original picture shown on p.37 of the Aspern & Wagram Campaign booklet, has a caption referring to the Vienna Volunteers being led by a "Landwehrleutnant". As that picture shows, many of their uniforms were similar to the local Landwehr force (in this case, Lower Austrian).

The Inner and Lower Austrian Landwehrs are well- documented, but the 1809 Bohemian and Moravian uniforms are poorly covered. As above, the Bohemian and Moravian Freiwillige (Archduke Charles Legion/Moravian Volunteers), who wore brown jackets can be confused with Landwehr units. However, in his 'Geschichte der kuk Wehrmacht' (1894), published by the Kriegsarchiv (War Archives) in Vienna, Wrede states in Vol. 5, p.144, that the Bohemian and Moravian Landwehrs had grey coats and blue facings. While not always accurate, as part of the Vienna military establishment, he must be considered more reliable than Ottenfeld or French sources, (notably Trainie & Carmigniani), whom modern writers rely on without question.

Within Bohemia and Moravia-Silesia (now the Czech Republic) in 1809, the situation is further complicated by the 1800 Archduke Charles Legion, which was a forerunner of the 1809 formations and so gets confused with them. In his MAA1 76: Austrian Infantry at Plate G4, Haythornthwaite shows what is said to be a Bohemian Landwehrman, (based on a b/w drawing in Ottenfeld). It is in fact an 1800 Legion soldier, although aside from the headgear that 1800 uniform is similar to the 1809 Freiwillige Legion.

Alongside Ottenfeld's original illustration, there is also a black and white drawing of a supposed 1809 Moravian Landwehrman in a regular J.5ger uniform. In the Osprey Plate caption, Haythornthwaite also refers to a Prague Student Battalion in 1809, which only existed in 1800. However, 1800 uniforms (and flags) were being reused in 1809, mostly by Freiwillige units. The Landwehr were desperately short of funding and so would have worn whatever material, including old 1800 Legion uniforms that was available.

There were three sources of brown material in the area. First there was the mottled lighter brown (officially greybrown) Oberrocks of the regular army that were stored in the depots in the area. A second source was the darker artillery brown material used by the Freiwillige, whilst third was the average peasant's clothing. Contemporary pictures of Bohemian mountain peasants of 1811 show a winter coat in brown, while Austrian peasants are shown in grey clothing. As mentioned above, the Lower Austrian Landwehr coats were designed in the looser (winter coat) style. The Prague uniform was more likely to be as regulated because they were close to major depots - the more distant Bohemian formations, who would have worn simple peasant clothing. Unfortunately, the corresponding Moravian peasants are shown in white and blue clothing, albeit decorated with red.

Geissler's contemporary picture (p.39 of MAA299) shows 1809 Bohemian Landwehr wearing Oberrocks and a variety of headgear. As in Austria and Bohemia, many units used their local Line regiment's facing colour in place of the official light blue. (Many of the Landwehr officers and NCOs would have been drawn from the regulars.) The sign of a Freiwilliger was a pointed red cuff, but some Line infantry regiments from Moravia-Silesia used various shades of red on their round cuffs. These included IR1 Kaiser (dark red), IR8 (scarlet), IR40 (carmine red until 1810) and IR57 (pale red), which the local Landwehr may have copied. This practice was adopted for the 1813 battalions, which were directly attached to each regiment.

In 1809, the Moravian-Silesian Line regiments were organised as follows: IR1 and IR7 based in Prerau; IR8 in Iglau; IR12 in Upper Olmutz; IR15 in Lower Olmutz; IR20 & IR57 in Troppau (Silesia); IR22 in Znaim; IR29 & IR10 in Brunn; IR40 in Hradschin; IR56 in Teschen.

There was the '1st Battalion syndrome', which refers to the tendency for the first battalion to have any new equipment that was available whilst the other battalions had to make do with older equipment. Without reliable or consistent information, I would be reluctant to start being definite about Landwehr uniforms. However, certainly about half the officers and NCOs should be in Line uniforms as seconded or recalled troops, while the officers drawn from local worthies probably had the officer cut uniforms, purchasing them themselves. The men should be roughly the same for each company, although varying somewhat across each battalion, (especially in the provision of gaiters).

The troops from the major bases around Olmutz and Brunn are more likely to have been in the grey-brown Line Oberrock with some in artillery brown. Given Moravia's close proximity to Lower Austria, it is likely that the grey coats got as far as Znaim, Br6nn and Hradschin, while the others would have relied on local Line supplies. Unfortunately, there wasn't the space to add all this into the Osprey, hence the use of the word 'imitate', rather than 'copied'. The Moravian Landwehr probably mostly had brass buttons and the Bohemians white metal.

Based on Trainie and Carmigniani, Haythornthwaite gives the uniform of the Prague City Landwehr as a long brown coat faced green, with white trousers and a black shako which had a yellow-black pom-pom and brass plate. A contemporary illustration of the Prague Landwehr in the Army Museum shows grey coats, which is also more likely as the brown material was used by artillery and Freiwillige formations, although these Landwehr are wearing shakos. It needs more research, but I suspect the brown/green uniform may be that of the Lobkowitz Jager battalion, raised in Prague by the Lobkowitz family, which joined the field army at Wagram along with a composite Prague Landwehr battalion. This is supported by green facings, which were often used by Jager formations. Thus far it can only definitely be said that the Lobkowitz Jager cartridge boxes (p.33 of MAA299) carried a brass plate with the family arms and that their drum (now in the Prague Military History Museum) has the arms painted on it.

Another unit which illustrates the muddled writing on this subject is Bowden & Tarbox's reference to "IR34 Cavriani" at Wagram. IR34 was a Hungarian regiment, whose Inhaber (and title) was Davidovich. Cavriani was the commander of 5th Lower Vienna Woods Landwehr Battalion (Lower Austria) - some Frenchman presumably remembered the red facings, but failed to distinguish Line from Landwehr, although that would appear to confirm that this battalion did use the proper Lower Austrian facing colour.

Kurassier:

- 1st Kaiser Franz I Bohemia

2nd Erzherzog Ferdinand d'EsteUpper/Lower Austria

3rd Herzog Albert von Saxe-TeschenNorthern Moravia and Silesia

4th Kronprinz FerdinandUpper/Lower Austria

5th Sommariva Styria/Carinthia

6th Gottesheim/(23 May 1809)

Prinz Moritz von LichtensteinMoravia/Silesia

7th Prinz Karl von LothringenMoravia/Silesia

8th Hohenzollern-Hechingen Bohemia

Dragoons:

- 1st Erzherzog Johann Styria/Carinthia

2nd Hohenlohe Upper/Lower Austria

3rd Wurttemburg (vakat)/6 April Knesevich Moravia/Silesia

4th Levenehr Moravia

5th Savoyen Upper/Lower Austria

6th Riesch Bohemia

Chavauleger:

- 1st Kaiser Franz I Moravia

2nd Hohenzollern Moravia/Silesia

3rd O'Reilly Bohemia

4th Vincent 'Lower Austria,

5th Klenau Bohemia

6th Rosenburg Bohemia

Uhlans

- 1st Mervelt East Galicia

2nd Schwartzenberg West Galicia

3rd Erzherzog Karl East Galicia

Hussars

(All recruited in Hungary except where Siebenburgen is listed)

- 1st Kaiser Franz I Alt-Ofen (Old Buda)

2nd Erzherzog Josef Siebenburgen

3rd Erzherzog Ferdinand d'Este Ofen (Buda)

4th Hessen-Homburg Funfkirchen

5th Ott Odenburg (Sopron)

6th Blankenstein Grosswardein

7th Lichtenstein Funfkirchen

8th Keinmeyer Pressburg

9th Frimont Veszprim

10th Stipicz Kaschau and Eperies

11th Szeckler Haromsecker, Czisker, Aransoyer, Fogaraser, Hunyader (Siebenbergen)

12th Palatinal Jazygier, Kumanier, and Hayduck

Mr. E. Jeanneau from Paris asked about:

A) The recruiting districts for Line infantry and cavalry 'in

1809; and B) The organisation of the Sedentartruppen in Hungary

and Siebenburgen (ie: their Insurrections):

ANSWER:The infantry will be covered in an Osprey Warrior

booklet on the Austrian Infantryand Grenadiers of the Wars, due

out inlate 1998. The cavalry arrangement is not shown for 1809

in the existing MAA 181, but was as follows:

The Hungarian, Siebenburgen and Croat-Slavonian

Insurrections (discussed on pp.36-40 of MAA 299) formed the

SedentArtruppen of the eastern parts of the Empire, but their

organisation like their equipment was very limited. These troops were

formed up and used according to the course of the war, being home

area defence units, those areas under immediate threat sending their

troops to reinforce the field army. Thus they were usually in ad hoc

brigades and mixed with regular troops, elements of the Croat-

Slavonian Insurrection fighting at Graz (25/26 June 1809) and

Hungarian Insurrection at Raab (14 June 1809). As well as fighting in

those battles, Landwehr infantry from the western Habsburg lands

were mixed with line units at Wagram.

The Insurrections were organised as single provinces in Civil

Croatia/ Slavonia and Siebenburgen, but in Hungary, the Insurrection

was divided into the four districts of Above/Below the Danube and

Above/Below the Thiess, each being officially headed up by a

Feldmarschalleutnant, all of whom were subordinate to the Archduke

Palatine Joseph. However, this was more related to raising and

organising the Insurrection than its deployment in the field.

Back to Age of Napoleon 26 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1998 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com