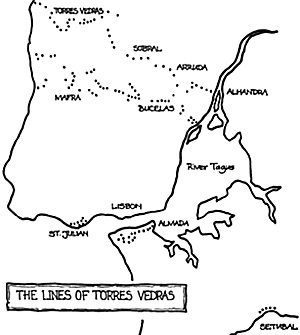

The two great chains of defences north of Lisbon

have received considerable attention from

historians. The third chain of the Lines of Torres

Vedras, around the small bay of St. Julian south of

the capital has, on the other hand, all too frequently

been ignored.

The two great chains of defences north of Lisbon

have received considerable attention from

historians. The third chain of the Lines of Torres

Vedras, around the small bay of St. Julian south of

the capital has, on the other hand, all too frequently

been ignored.

In some respects the third line was the most vital of them all. This was to be the British army's secure embarkation point. If Wellington had been unable to persuade the British cabinet that he could safely withdraw the army in the event of a serious defeat he would not have been granted permission to attempt the defence of Portugal.

Such was the anxiety of the Government for the safety

of the army in the Spring of 1810 that the Secretary of State

for War was obliged to tell Wellington "that a very

considerable degree of alarm exists in this country

respecting the safety of the British army in Portugal".

Wellington's plans for a safe evacuation, therefore, were a

prominent feature of his dispatches during this period. He

informed Lord Liverpool that if he were provided with a

"large fleet of ships of war, and 45 disposable tons of

transports, I shall try , and I think I shall bring them (the

British army) all off". [1]

This did not allay Liverpool's fears, who replied that

"the chances of a succesful defence are considered

here by all persons, military as well as civil, so improbable that I could not recommend any attempt at what may be called desperate resistance".

[2]

He consequently advised Wellington that he would

"be excused for bringing away the army a little too

soon, than, by remaining in Portugal a little too long,

exposing it to those risks from which no military operations can be wholly exempt".

To this, Wellington replied that "all the preparations for

embarking and carrying away the army, and everything

belonging to it, are already made, and my intention is to

embark it, as soon as I find that a military necessity exists

for so doing. I shall delay the embarkation as long as it is in

my power, and shall do everything in my power to avert the

necessity of embarking at all.

If the enemy should invade this country with a force less than that I should think so

superior to ours as to create a necessity of embarking, I shall fight a battle to save the country, for which I have made the preparations; and if the result

should not be successful, of which i have no doubt, I shall

still be able to retire and embark the army .... (However),

if we do go, I feel a little anxiety to go like gentlemen, out

of the hall door (particularly after all the preparations I

have made to enable us to do so), and not out of the back

door". [3]

Wellington had indeed made his plans to "go like

gentlemen". As early as October 1809, Wellington had

reminded Colonel Fletcher, his chief engineer that "the

great object in Portugal is the possession of Lisbon and

the Tagus, and all our measures must be directed to that

object. There is another also connected with that first

object, to which we must attend, viz., the embarkation of

the British troops in the case of a reverse".

[4]

Because of the rocky nature of the coast of

Portugal there are very few spots suitable for such a

major operation, and only four places were given any

serious consideration. Admiral Berkely, who commanded

the Royal Navy squadron stationed in the Tagus,

suggested the little bay of Paco d'Arcos. Wellington

rejected this as it was within artillery range from the

south bank of the Tagus, and it was Wellington's firm

belief that the French would "attack on two distinct lines,

the one south, the other north, of the Tagus."

[5]

The second place to be investigated was Peniche.

This was a small peninsula some forty miles north of

Lisbon. It was already strongly fortified and was virtually

impregnable. In December 1809, Peniche was inspected

by Marshal Beresford's chief of staff: "The isthmus over

which the peninsula is approached is covered with water

at high tide, and from the line of works describing a sort of

arc, very powerful cross-fires may be established on

every part of it. There are nearly 100 good guns upon the

work, the brass ones especially good. This is the most

favourable position that can be conceived for embarking

the British army, should it ever be necessary to do so. The

circumference abounds with creeks and clefts in the

rocks, inside which there is always smooth water, and

easy egress for boats. They are out of reach of fire from

the mainland: indeed, there is sufficient room to encamp a

large force perfectly beyond the enemy".

[6]

Peniche was favoured by the British

Government who saw it as a second Gibraltar which

"might be held by England, even if Portugal otherwise

were in the power of the enemy... If it be the wish of

Lord Wellington he can retire upon Lisbon, give battle in

front of it, and if the day go against him. Retreat upon

Peniche and defend it so long as he pleases".

[7]

Wellington knew that he could hold Peniche

against attack almost indefinately. But if the French attack

was delivered between June and November, when the

Tagus was fordable, the allied army could well be forced

to withdraw eastwards for fear of of exposing its flank. A

retreat to Peniche would then be impossible. In addition,

the main Lines of Torres Vedras were only twenty-two

miles north of Lisbon and Peniche would be well outside

these defences. For this reason, despite its obvious

strengths, Peniche was discounted as the final embarkation point.

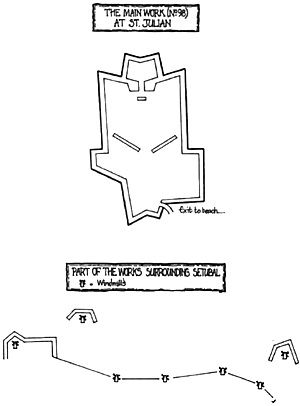

As none of these places was regarded as being

satisfactory, Wellington instructed Colonel Fletcher to

investigate the coast line South of Lisbon. Fletcher

reported that the small bay of St. Julian, was far from

ideal:. "at intervals, such a sea rolls in for days together

that no boat can with safety approach the shore". It could,

however, be made secure enough to allow an

uninterrupted embarkation. Just a few miles below the

capital, the bay was partially sheltered by a rocky

promontory. Upon this was built the Sixteenth century fort of

Sao Juliao de Barra. This fort "from its extravagantly high

scarps and deep ditches", recorded Major John Jones,

Fletcher's second-in-command, "can never be successfully

assaulted against the slightest opposition".

[8]

[1] Gurwood, J. (Ed.) The Dispatches of Field Marshal

the Duke of Wellington, 1835-38, vol. 5, pp.446-9.

Appendix: Works Comprising the Lines of Torres Vedras (Charts: slow: 177K)) Campaign in Portugal: Part II (AoN27) Many of the redoubts of the Lines were originally constructed

entirely from earth, but after the first winter it was found that with any face that

was cut at an angle greater than 45 degrees the soil was washed away by heavy

rain.

Many of the redoubts of the Lines were originally constructed

entirely from earth, but after the first winter it was found that with any face that

was cut at an angle greater than 45 degrees the soil was washed away by heavy

rain.

Earthen traverses were built inside many of the larger redoubts of the Lines to act as secondary defensive positions. In the background can be seen two stone-built powder rooms.

Earthen traverses were built inside many of the larger redoubts of the Lines to act as secondary defensive positions. In the background can be seen two stone-built powder rooms.

The next place to be considered was Setubal. This

town, now an important commercial and fishing port, lies

over twenty miles south-east of Lisbon. Wellington

calculated that Setubal could be held for eight days and

would be a practical point for embarking the army. Being

on the south side of the Tagus, however, meant that

Setubal could be cut off by a French army operating in the

Alemtejo. Although it was therefore unsuitable as the main

embarkation point, Setubal was not completely ignored.

The ground around the bay was fortified and prepared as

a secondary embarkation area.

The next place to be considered was Setubal. This

town, now an important commercial and fishing port, lies

over twenty miles south-east of Lisbon. Wellington

calculated that Setubal could be held for eight days and

would be a practical point for embarking the army. Being

on the south side of the Tagus, however, meant that

Setubal could be cut off by a French army operating in the

Alemtejo. Although it was therefore unsuitable as the main

embarkation point, Setubal was not completely ignored.

The ground around the bay was fortified and prepared as

a secondary embarkation area.

Notes

[2] Supplementary Dispatches and Memoranda of Field

Marshal the Duke of Wellington, 1858-72, vol. 6, p.463.

[3] Dispatches, vol. 6, pp.6-7.

[4] Dispatches, vol. 5, p.235.

[5] Ibid.

[6] B. Durban, The Peninsular Journal of Major-General Sir

Benjamin Durban, 1930, p.74.

[7] Wellington wrote the following to Admiral Berkely from

Lisbon on 26 October 1809: Peniche - I conceive that I

should be able to hold this place during any length of time

that might be necessary for an embarkation; but ... in the

event of the attack being made between the months of June

and November, when the Tagus is fordable, the operations

of the army would be carried on in a part of the country

which would be cut off from Peniche and the retreat to that

place would be impracticable...

[8] J. Jones, Memoranda Relative to the Lines Thrown up to

Cover Lisbon in 1810, 1846, p.5.

Back to Age of Napoleon 26 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1998 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com