The 95th Regiment of Foot was Britain's first composite light infantry unit, raised soleley as a 'rifle' regiment. Although raised at a much later date than many continental rifle units, the 95th soon surpassed all of them in skill and military professionalism. Trained, uniformed and armed in a way that differed from the regular troops of European armies, they can be said to be the first 'thinking' fighting soldiers.

The 95th Regiment of Foot was Britain's first composite light infantry unit, raised soleley as a 'rifle' regiment. Although raised at a much later date than many continental rifle units, the 95th soon surpassed all of them in skill and military professionalism. Trained, uniformed and armed in a way that differed from the regular troops of European armies, they can be said to be the first 'thinking' fighting soldiers.

The 95th Regiment's excellence was basically due to a combination of revolutionary training, new advanced equipment and uniform, brilliant leadership and an impregnable morale - the essential ingredients for an elite force.

The Experimental Corps of Riflemen

What was to become the 95th Regiment began life in 1799 when Colonel William Stewart suggested, in a memorandum to the Duke of York, that an 'experimental corps of riflemen' should be created. The idea was accepted by York who, after witnessing the failure of the rigid tactics of his redcoats in Holland (1793-1795), recognised the need for an antidote to the French Tirailleurs, who went before the main attack harassing the enemy line.

As a consequence of the memorandum, he sent a circular to 14 line regiments asking them to supply 33 NCOs and men each, who were to be sent to Blatchingdon barracks at Horsham. There they would begin training under Stewart and the equally able Colonel Coote Manningham. On arrival, the men were divided into companies, issued with new green uniforms and were trained in light infantry tactics as well as field craft and marksmanship.

In July 1800 the training school was dissolved and most of the experimental corps of riflemen took part in the ill-fated attack on Ferrol. The school however was subsequently re-instated, Manningham obtained permission to begin recruiting and approval was then given for the unit to be made permanent. The corps next saw action in December 1800 when a company commanded by Sidney Beckwith served as marksmen on board Nelson's flagship during the bombardment of Copenhagen. Here the Rifles won their battle honour on 2 April 1801.

The 95th is born.

During 1802, using the remaining nucleus and recruits taken from regiments stationed in Ireland (each supplying 12 good men), the corps moved to Shorncliffe in Kent. Together with the 43rd and 52nd Light Infantry, training commenced under Sir John Moore. Moore was a veteran who had served in America, Corsica, the West Indies, Holland, Ireland and Egypt. He was a talented commander who, had he not been killed at Corunna, would perhaps have surpassed Wellington as one of Britain's greatest generals.

With the end of the Peace of Amiens and the renewal of war with France, the Experimental Corps of Riflemen was brought into the line on 18 January 1803 as the 95th (Rifle) Regiment of Foot. A second battalion was raised in 1805 at Canterbury to deal with an increasing number of recruits, and in 1809 a third was raised and sent directly to Cadiz. Battalions aided many of the British expeditions between 1803 and 1808 (for example, Whitelock's botched campaign to take Buenos Aires in 1806), bu gained most fame during the Peninsula War (1808-14) as part of the elite Light Division under Robert (Black Bob) Craufurd.

On the retreat to Corunna they upheld the honour of the British Army virtually single-handedly, acting as the rear-guard. Although the campaign was ultimately a defeat, their conduct was wholly victorious. Whilst having no real " ancient" regimental history to draw upon, they relied on team spirit and excellence to create a magnificent espirit de corps.

Training

Training

The Rifles' training varied greatly from that of the line regiments, and a whole new and revolutionary system was developed based on trust between officers, NCOs and men, to maintain discipline and standards. This system aimed to make each rifleman a thinking fighting man rather than an automaton able only to follow the commands of an officer. The men were given self respect and professional pride, being made to understand the reasons why they should excel at their various tasks.

The new system of training was influenced by the regulations of Baron de Rottenberg of the 60th Regiment, which aimed to cultivate a feeling of trust and family spirit within each company. Careful instruction was to be relied upon to train men, rather than brutal punishment, and the men of each platon were never to be seperated. Aan individual esprit de corps flourished allowing units to operate successfully when divorced from each other in the field. In this way, comradeship, and even friendship could grow between officers, NCOs and men.

Moore conducted exercises and manoevres under conditions as close as possible to war itself, and special exercises were devised, allowing the men to march and drill as if on campaign, rather than on the parade ground. The Rifles were also trained in a number of special skills, which would prove invaluable to them in the field. The quick march, for example, was developed (140 paces per minute) to allow large distances to be covered in the shortest possible time without excessive fatigue. The Rifles were soon to perfect this quick march to an art which was to aid them throughout the Peninsular when fighting either as vanguard or rearguard as well as in innumerable skirmishes.

Other practical skills were also taught, such as field craft, judgement of range, terrain use, and quick thinking, as well as launder and cobble within squads, and bivouac anywhere.

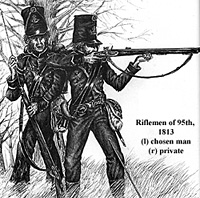

Marksmenship was a major part of the training, making them good skirmishers and helping the men respect their comanding officers by rewarding the best shot in the company. All riflemaen wore the black cockade on their shako; this was the first class of "Awkward Class" cockade. A second class shot would have a white cockade over the black one, while a third class shot (best) would wear a green cockade over the black.

Other prizes were awarded for long service and good conduct, plus sporting and shooting competitions. For example, a "chosen man" in every half-platoon, who, in the absense of the NCO, would take charge of the squad.

By humane practical training, the rifles became fast marching, sharp shooting, 'skirmishing'fighting men. They were not only given greater confidence in their own abilities, but were made part of an elite team in whom they could trust and rely. In brief, as well as fighting in line like regular troops, the riflemen fulfilled various other roles but were principally skirmishers and an antidote to French voltigeurs and Trailleurs.

In battle they would fight in extended order at the head of the main body of troops or on their flank. They skirmished in front of important positions to deal with the enemy light infantry or to harass the enemy ranks, and would scout and reconnoitre whilst on the march. Usually they would form the vanguard or rearguard, (for example, as on the previously mentioned retreat to Corunna in 1808-9) being a highly mobile elite.

In their role as skirmishers the contingent of riflemen would divide into two. One half formed the skirmish line or chain (in extended order) whilst the other half would form a reserve in line with the main force. The riflemen would advance in pairs, one firing whilst his partner spotted for him, reloading his Baker rifle at the same time.

Commands were given by bugle (not drum) and by the officer's whistle. The chain of pairs advanced forward to pick off the enemy officers and other important targets using a mixture of fire and movement. They would then move back to join the ranks as the main attack was delivered.

Service Uniforms, Weapons and Equipment from 1802

The Jacket Rifle officers wore a Hussar-style uniform, with a Dolman and Pelisse. The dolman-style service jacket was dark green, and had twenty-two black braid loops running down its front, as well as two rows of silver buttons on the right side and one on the left. The braid loops tapered from seven and a half to two and a half inches, and were knotted at the end in typical Hussar fashion. The collar was of black velvet, as were the cuffs, which were pointed and had five silver buttons down on the rear seam. There were black silk loops on the collar front, and also on the rear of the jacket, curving down from shoulder to hip.

The Jacket Rifle officers wore a Hussar-style uniform, with a Dolman and Pelisse. The dolman-style service jacket was dark green, and had twenty-two black braid loops running down its front, as well as two rows of silver buttons on the right side and one on the left. The braid loops tapered from seven and a half to two and a half inches, and were knotted at the end in typical Hussar fashion. The collar was of black velvet, as were the cuffs, which were pointed and had five silver buttons down on the rear seam. There were black silk loops on the collar front, and also on the rear of the jacket, curving down from shoulder to hip.

The Pelisse (which appeared in 1804) was similarly dark green, and had black silk loops like those of the dolman, as well as an edging of dark grey or brown fur. A toggle and cord on the garment also allowed it to be fashionably suspended over the shoulder.

Private soldiers and N.C.0s. were dressed in a similar uniform - a jacket of "Rifle Green" which was single breasted, and adorned with three rows of silver metal buttons (thirty-six in all). The jacket had no turnbacks, only a short tail that sloped back in imitation of them. The cuffs, collar and epaulettes were black, edged with white lace.

Trousers

Officers had green breeches and hussar-style boots, but cavalry-style overalls would be worn on campaign.

NCOs and men were of rifle green like the jacket and worn inconjunction with dark gray or black gaiters. On campaign, probably gray trousers and locally-acquired items would be worn.

Headgear

Officers wore a cylindrical shako-like cap which had a moveable peak to give the impression of a "mirliton" style hussar cap. The cockade, cord, and tuft, were all dark green.

Other ranks wore a stove-pipe shako bearing the light infantry hunting horn badge, a cockade, and a green cord that ran from the front of the cap diagonally to the rear. A green worsted tuft was also worn above the cockade. After the introduction ofthe belgic shako in 1812, theheadgear remained unchanged.

Weapons

The 95th were armed with the renowned Baker rifle that was carried by men, NCOs and by some officers on campaign. The Baker was four-feet long, and the addition of a sword bayonet brought it the overall length to five feet ten inches. It weighed nine and a half pounds, being rifled with seven grooves at a quarter turn. It fired a 0.625" bullc..

All furniture was in brass. The rifle had a brass box built into the butt that contained ammunition and tools used for cleaning the rifle's lock and for extracting a misfired bullet. These tools consisted of a 'picker and brush', a small screw driver to take off the side plate, a one-inch iron nail that was used to hold the tension of the mainspring when the cock was dismounted, a small round oil can and a worm screw that fitted on the ramrod to draw a mix-fired bullet. A metal bar to give leverage on the ramrod when screwing down was also provided. A wooden mallet issued to assist the use of the ramrod was unpopular and was quickly discontinued.

N.C.0s. and men also carried a 22 inch sword bayonet, whilst officers carried a curved sword. This latter weapon was described in John Kincaid's memoirs as "our small regulation half moon sabre...better calculated to shave a lady's maid than a Frenchman's head".

Equipment

The rifleman's webbing and equipment were of black leather, and consisted basically of a black crossbelt and waistbelt. To the waistbelt was attached a standard cartridge pouch that contained ready-made powder and ball ammunition for quick firing. A smaller pouch was also attached to the waistbelt. This contained separate balls and patches for precision firing. These were to be used in conjunction with a powder horn mounted on a green cord and held along the length of the crossbelt by leather 'pipes'.

The usual infantry equipment, consisting of a knapsack, canteen, bedroll and back-pack were also carried. The back-pack, made by Trotter's of Soho Square London, was commonly known as "Trotter's Pains" as it was highly uncomfortable due to its wooden frame and tight fitting straps. It was often replaced by the sturdier and more comfortable French packs, taken from a fallen enemy.

The officer's pattern crossbelt incorporated a whistle for rallying the troops. This was ounted on a chain suspended from a metal disc in the shape of a lion's head attached to the centre of the crossbelt. In addition to this, officers also wore a scarlet sash as a badge of office.

Rank Insignia

Sergeants: Wore a scarlet sash, with a black stripe running down the centre, white lace chevrons (three for sergeants and four for sergeant-majors) and carried a cane, which could be suspended from one of the jacket buttons.

Corporals: Wore one white lace chevron (lance-corporals wore two).

Chosen Men: Wore a stripe of white lace around the upper arm.

Acting N.C.0s. Wore a sword badge on the right arm.

Bibliography

G Caldwell & R Cooper Rifle Green at Waterloo, 1990

M. Chapel: British Infamry Equipments, 1808 1908, Osprey 107, 1980

S Fosten: Weilington's Infantry (2), Osprey 119, 1982

PJ Haythornthwaite Uniforms at Waterloo, 1991

PJ Haythornthwaite The Napoleonic Sourcebook, 1991

L James The Iron Duke, 1992

N. Leonard: Wellington's Army in Colour Photographs, 1994

J. Strawson: Beggars in Red, 1991

M. Windrow & G Embleton Military Dress of the Peninsula War, 1991

Back to Age of Napoleon No. 23 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1997 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com