On May 12th, 1812, Ensign John Mills, of the 1st battalion Coldstream Guards, came in from beneath the fiery Portuguese sun. He sat down at his portable writing desk in his quarters at Castelo de Vide, a few miles north of Portalegre. After dippinghis quill in ink fashioned from gunpowder mixed with wine, he began to write to his mother in England.

On May 12th, 1812, Ensign John Mills, of the 1st battalion Coldstream Guards, came in from beneath the fiery Portuguese sun. He sat down at his portable writing desk in his quarters at Castelo de Vide, a few miles north of Portalegre. After dippinghis quill in ink fashioned from gunpowder mixed with wine, he began to write to his mother in England.

"I keep a private diary myself merely to mark the day. Some years hence I shall look over it with pleasure." John Mills would be amused to know that some 183 years later, his journals and letters written on the campaigns between 1811 and 1814 have been published. They are being enjoyed with equal pleasure by today's historians, eager to discover more about what life was like in Wellington's Army in the Peninsula.

John Mills

John Mills was twenty years old when he was commissioned as an ensign in the Coldstream Guards on December 21st 1809. It was to be another year before he set sail from England, bound for Lisbon where he disembarked in January 1811. It would be a further three months before he finally caught up with his battalion, at Puebla, on April 18th 1811.

Apart from a couple of his letters that appeared in J.W. Fortescue's Following the Drum, in 1930, which apparently attracted little interest, Mills' letters and diaries have lain unpublished and dormant since he put down his pen in Holland in the winter of 1813-14. He wrote over fifty very extensive letters and kept a diary with entries for every single day between April 1811 and December 1812. Given the extent of the correspondence this comes as a great surprise and one is moved to ask whether there are similar extensive memoirs still to be published, which there probably are.

The importance of John Mills' letters and diaries lies not only with their content, with is very extensive to say the least, but in the fact that unlike the majority of Peninsular War memoirs, Mills' are contemporary and were written in camp whilst on campaign. He needed no key to unlock his memories in the way that so many of Wellington's men did. That key was often Napier's War in the Peninsula which, appearing in 1832, rekindled fading memories for many veterans who were subsequently moved to put pen to paper. As far as Mills was concerned the war was changing from one day to the next. He was not writing with the benefit of hindsight. One day Wellington is all-conquering, the next he is an ass. On another occasion, the British army has all but defeated the French but the next there seems no hope at all and an evacuation appears likely.

Candid Obervations

Mills' letters and diaries list everything from the lengths of marches, to battles and sieges, to the local agriculture, people, the guerrillas, and his thoughts on Wellington and other Allied commanders. John Mills had no qualms about criticising any of the Allied commanders and, indeed, Wellington, Beresford and Graham all come in for their fair share of censure. Beresford, in particular, comes in for some real savaging as a result of his handling of the battle of Albuera.

On June 27th 1811, six weeks afte the battle, Mills wrote, We are all here much surprised at the Vote of Thanks to General Beresford. Good John Bull, how easily art thou duped. General Beresford is the most noted bungler that ever played at the game of soldiers, and at Albuera he out-bungled himself. Lord Wellington, riding over the ground a few days after observed that there was one small oversight; that his right was where his left should have been. I have learned one thing since I have been in this country and that is to know how easily England is duped; how completely ignorant she is of the truth of what is going on here, and how perfectly content she is, so long as there is a long list of killed and wounded.'

On March 25th 1812 the Coldstream Guards formed part of the force covering the siege of Badajoz. Camped near Albuera, Mills wrote, 'On our march to Santa Martha we passed over the field of Albuera. The numerous bones and remnants of jackets still tell the tale and I cannot help wondering that so nefarious a military delinquent should still wear his head, and regretting that it should be in the power of a fool to throw away the lives of 6,000 men. The ground he chose convicts him. He had the choice of two positions 200 yards distant from each other, chose the worst and lost his men in taking up the other after he had perceived his error.'

Wellington Subterfuge

Wellington himself is accused of misleading the British government and public by the tone of his despatches. Shortly after the battle of Fuentes de Onoro, Mills wrote, 'At Fuentes, the French completely turned our right; Lord Wellington in his despatch slightly notices it, and would lead you to think that the troops on the right were withdrawn rather, than as was the case, driven in. And then they give him what he himself never dreamt of claiming, a victory.'

This theme was echoed by Mills on September 3rd 1811. He wrote, 'at the end of a few years, people will open their eyes, and see they have been humbugged and even now, if they would divest themselves of prejudice and think for themselves they would see the error. Lord Wellington is a great general, but beats even the Dean of Ch Ch at humbug.' The Dean of Ch Ch, incidentally, was the Dean of Christ Church, Oxford, a noted orator with a tendency to ramble on. Mills is particularly hard on the way in which Wellington wrote some of his despatches. We know that other officers were irritated by his lack of praise, Hinuber at Bayonne and Colborne at Waterloo, for example.

During the siege of Burgos Mills wrote, 'Wellington seems to have got into a scrape. His means are most perfectly inadequate and he has already lost 1,000 men. To shift the blame upon others he complains they do not work well. In short, durinc the whole of this campaign from the tone of his orders, it would appear that the conduct of the army had been mad. The few words he said after the Battle of Salamanca had more censure than praise. This is not the way to conciliate an army.'

From Burgos to Salamanca

John Mills took part in the retreat from Burgos and when he reached Salamanca wrote, 'Our want of success at Burgos and the subsequent retreat will cause a great deal of dissatisfaction. England, I think it has turned the tide of affairs here and Spain I think is lost. If ever a man ruined himself the Marquis has done it; for the last two months he has acted like a madman. The reputation he has acquired will not bear him out - such is the opinion here.' Fortunately, Wellington was able to reverse the tide of war and emerged victorious.

Aside from the wider aspects of the war, John Mills was forever keeping his family informed as to his daily routine and pastimes. On May 8th 1811 he wrote, 'I never was better in my life. Before we came into the field I was not quite right, but since, I have not even had a cold. I am tanned to the colour of a dark boot top, and my hands from not wearing gloves to two degrees darker than mahogany. We have been well supplied with bread, chocolate and lemonade, which have been three articles of sale here, and at this moment I hear a man crying lemonade, which appears a little out of character for a field of battle.'

He also wrote down details of his own establishment; 'a horse, Docktail, who was

taken from the French at Salamonde - a great favourite. Two mare mules, Bess and Jenny. Both are very quiet. A small he mule; Turpin, a rogue, he carries William. Mare mules carry the baggage and I ride Docktail. My servants consist of William, a private servant, Duckworth, a soldier servant who looks after the animals, and Joseph, a Portuguese boy under him.'

Goodness knows what the baggage train of Wellington's army really looked

like.

New Uniforms

In October 1811 he wrote home, in some alarm, at the news that army uniforms were to change. 'We are all in consternation at the idea of the dress of the army being altered from cocked hats and coats to jackets and caps. Ye heavens, what will become of crooked legs, large heads, and still hinder parts?'

Mills also makes one of the few references to a contemporary account of the war when writing home on May 28th 1812. The book in question was Captain William Stothert's A Narrative of the Principal Events of the Campaigns of 1809, 1810 and 1811, which was

published in 1812.

Of the book, Mills wrote, 'A Captain Stothert, Adjutant to the 3rd Regiment of Guards, has published a narrative of the campaign in this country. I am told it is a miserable performance, resembling a log book, containing the precise hour in the morning that the Guards marched, and

the exact period of their arriving at the end of the march.' The reader will be able to better judge for him or herself when Ken Trotman Ltd republished it next year.

There are dozens of interesting pieces throughout the correspondence including

references to the Heroine of Zaragossa, prisoners-of-war, the movements of the

respective armies, the guerrillas, sham fights and mining schools. He also has some

interesting pieces on Britain's allies, in particular the reluctant Portuguese conscripts

who were hauled to the front in irons.

This is not forgetting the battles and sieges, of course, which include Fuentes de

Onoro, Salamanca, Ciudad Rodrigo, Badajoz and numerous minor actions. The best and

most extensive account, however, is saved for Burgos and is without doubt one of, if not the

finest descriptions of that particularly miserable episode to be published. Having

missed out on the stormings of both Ciudad Rodrigo and Badajoz, the 1 st Division of the

army, of which the Guards Brigade formed part, pleaded with Wellington to be allowed to

attack Burgos. Unfortunately, it turned out to be the biggest setback Wellington suffered in

the Peninsula. John Mills' account of the conditions in the trenches and of the unsuccessful attempts to storm the castle are tremendously vivid and succeed completely in conveying the desperate and tragic nature of the assaults.

Mills returned from Portugal in February 1813 and subsequently saw service in Holland during Graham's attempt on Bergen-op-Zoom. Unfortunately, he developed pneumonia and was sent home on sick leave, resigning from the army in August 1814.

Had he not been forced to resign he would have fought at Waterloo, where his battalion defended the chateau of Hougoumont. His post-military career is equally interesting. He was a great friend of Beau Brummel, was a Regency dandy in London, helped reform White's Club, raced yachts and horses and became an MP before returning to his country home to run his estate. The military tradition runs through the family. One of John Mills' great-grandsons, Major General Giles Hallam Mills, formerly of the King's Royal Rifle Corps, was Resident Governor of the Tower

of London between 1979-84. A remarkable man with great descriptive powers, John Mills' correspondence represents a great new insight into life as a soldier in Wellington's army in the Peninsula.

For King and Country: The Letters and Diaries of John Mills, Coldstream Guards, 1811-1814. Other Book Reviews

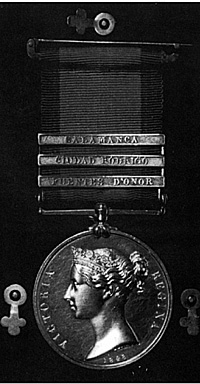

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. At right, Mills' Military General Service Medal, with clasps for Fuentes de Onoro, Ciudad Rodrigo, and Salamanca.

However, such comments are extremely interesting as barometers of the day. Again, it illustrates the importance of contemporary memoirs, written by men who had no inkling of what lay round the corner. As Oman wrote in his Wellington's Army, 'an officer writing of Corunna or Talavera with the memory of Vittoria and Waterloo upon him, necessarily took up a different view of the war from the man who set down his early campaign without any idea of what was to follow.' Mills, of course, was writing without the benefit of hindsight. Even with the memories of Ciudad Rodrigo, Badajoz, Salamanca and the entry into Madrid still fresh in his mind he was convinced that, after the retreat from Burgos, Spain was lost.

At right, Mills' Military General Service Medal, with clasps for Fuentes de Onoro, Ciudad Rodrigo, and Salamanca.

However, such comments are extremely interesting as barometers of the day. Again, it illustrates the importance of contemporary memoirs, written by men who had no inkling of what lay round the corner. As Oman wrote in his Wellington's Army, 'an officer writing of Corunna or Talavera with the memory of Vittoria and Waterloo upon him, necessarily took up a different view of the war from the man who set down his early campaign without any idea of what was to follow.' Mills, of course, was writing without the benefit of hindsight. Even with the memories of Ciudad Rodrigo, Badajoz, Salamanca and the entry into Madrid still fresh in his mind he was convinced that, after the retreat from Burgos, Spain was lost.

Edited by Ian Fletcher.

Published by Spellmount Ltd,

ISBN 1-873376-22-7.

297pp & 18 b/w plates.

Price 20 pounds

St. Faust in the North 1803-1804

Napoleonic and Waterloo: The Emperor's Campaign

Napoleonic Uniforms

Oman's Magnus Opus: A History of the Peninsula War

Back to Age of Napoleon No. 20 Table of Contents

© Copyright 1996 by Partizan Press.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com