The war against Revolutionary and Napoleonic France was as

much an economic battle as it was an armed struggle, and it led to a

remarkable rise in both Britain's population and its economic

output. An enormous number of men were placed under arms.

Towards the end of the war there about 130,000 in the Navy and

about 350,000 in the army, not counting the militia, volunteers,

yeomanry and East India Company forces.

The war against Revolutionary and Napoleonic France was as

much an economic battle as it was an armed struggle, and it led to a

remarkable rise in both Britain's population and its economic

output. An enormous number of men were placed under arms.

Towards the end of the war there about 130,000 in the Navy and

about 350,000 in the army, not counting the militia, volunteers,

yeomanry and East India Company forces.

In 1804 Lord Hawkesbury declared in Parliament that the

armed forces, including militia but not volunteers, represented

rather more than one in ten of the population of military age in

Great Britain and Ireland.

[1]

These men had to be fed and provided with arms, clothing and

equipment, or the means for paying for these things abroad had to

be found, for the British armies on the continent footed their bills

instead of living on the country. The working population had also

to find the means to pay Britain's allies abroad. Pitt's subsidies to

the allies were met by the export of goods, and it was estimated

that one worker could maintain two fighting men in the field. [2]

In 1793 the United Kingdom had a population of fourteen

to fifteen millions. The National Debt stood at £ 240 million,

and the annual expenses of government were between £ 18

and £ 19 million. Of this figure the Army and Navy

accounted for approximately one third of total expenditure. As the

normal revenue amounted to about £ 20 million, the

Government budgeted for a small surplus. The war changed all of

this. By 1815 the population had risen to some 20 millions and the

National Debt had reached £ 900 million with consequent

debt charges of 02 millions per annum. The Government's

expenditure was around £ 100 millions a year of which a

massive £ 56 millions went to the armed forces.

[3]

To support the increase in expenditure new ways of raising

revenue had to be found, and this led, in 1799, to William Pitt

introducing income tax into Britain for the first time. There were, of

course, many other forms of taxation but they were indirect taxes,

on goods and trade, which allowed each person, in theory, the right

to decide on what tax he paid. The new tax took away this long-

held right and was, unsurprisingly, extremely unpopular.

In 1816, with Napoleon safely marooned on St. Helena, the

tax was abolished and Parliament even voted for all Income Tax

records to be destroyed. Despite its unpopularity it was the first

British tax that was reasonably proportioned to means, and many

saw it as a fair way to raise money. A leader writer in the Times in

1803 supported the view that "the tax must, we think, be

accounted just and equitable as it leaves those persons who are

affected by it in precisely the same relative situation one towards

another, after its operation as they were previously to its

imposition." [4]

The rate of tax varied throughout the war. In 1801 the rate

was two shillings (10p) in the pound. Following the Peace of

Amiens in 1802 the tax was repealed, only to be re-introduced after

the renewal of hostilities. In 1803 the rate was one shilling in the

pound on incomes of £ 150 or above per annum, ranging

downwards to threepence (1.25p) in the pound on annual income

of between £ 60 to £ 150. Those with earnings below

£ 60 were exempt. This meant that the earnings of all

labourers and workmen, apart from a few prosperous artisans, were

exempt from the War Income Tax. the figure was finally settled in

1806 at two shillings, at which figure it remained until its abolition

in 1816.

[5]

The War Income Tax was made up of five "Schedules"

which, in reality, were five separate and distinct forms of taxation.

Schedule A was a tax on the rent of land and real property.

Schedule B was a tax on the produce of the land. Schedule C taxed

the interest received by the holders of Government funds, and

Schedule D was a tax on the profits from trade and commerce,

manufactures, professional earnings and salaries. Schedule E was a

levy on certain "offices, pensions and stipends."

[6]

Thus everyone with a sufficiently large income was caught

in the net. Schedule A taxed the landowners for quarries, mines and

ironworks, manorial dues, fines and general profits. Schedule B

taxed farmers, including owners who farmed for themselves, "in

respect of their profits from such an occupation."

[7]

Schedule C taxed the incomes from annuities, dividends and

shares payable to the Exchequer. Schedule D taxed the

businessmen, merchants and industrialists and it included a

"sweeping" clause taxing all forms of income not covered by the

other schedules. Finally, Schedule E taxed the incomes of state

employees.

It was perhaps inevitable that many would try to avoid the

tax. As the minimum tax level was £ 60 per annum a large

number of people declared their incomes to be between £ 50

and £ 60. Consequently in 1806 the tax-free allowance was

reduced to £ 50. The Tax Office Guide Book of 1806

explained that "the regulation in former Acts by which exemption

was granted on the whole of every person's income under £ 60

a year, which was intended to have a strict and limited operation,

has been introductive of the greatest frauds upon the public. It is

notorious that persons living in easy circumstances may, even in

apparent affluence, have returned their income below £ 60.

Hence it is that the legislature found the necessity of confining the

exemption to £ 50, that their former returns may be made use

of."

[8]

The result of the change was to bring a whole class of new

Income Tax contributors within the net.

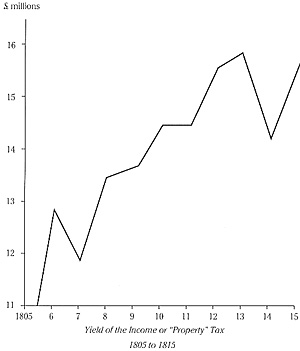

After this change, the lowest annual yield was £

11,905,858 in 1807, and the highest was £ 15,795,691.

Between April 1806 and 1816 the tax realised nearly

£ 142 millions and there is no doubt that Britain could not

have maintained the war at the level that it did had it not been for

this tax. Yet Income Tax was not the major source of revenue

during the war. [9]

It was the old Customs and Excise duties

which still accounted for around half of the Government's total

income. this was because the war had boosted the British economy

to unprecedented levels of activity - the Industrial Revolution was

gaining pace and Britain was established as the Workshop of the

World.

In 1805 the declared value of our exports was £

36,000,000. Of this amount Europe took £ 13,600,000, the

USA took £ 11,000,000, the rest of North and South America

£ 7,700,000, Asia £ 2,900,000 and Africa £

750,000.

In 1806 the Berlin Decrees were promulgated banning British

goods to Europe but trade continued to increase, and in 1810 total

exports were £ 45,000,000. Even so, the Government had to

resort to borrowing as taxation of all kinds amounted to only thirty-

five per cent of the additional expenditure created by the war, and

it has been calculated that Barings, the merchant bankers, with

other financial houses remitted £ 57,000,000 between 1792

and 1816 to Britain's Continental Allies. [10]

Despite the rejoicing in 1816 upon its abolition, Income tax

was to be return in 1842, but at a much lower level than during

the Napoleonic Wars. It was not until Britain was faced with

another major war, in 1914, that ministers dared to impose such

a burden upon the tax paying public.

Notes

[1] J. Lowe, The Present State of

England in regard to Agriculture, trade and Finance, 1823, p. 46

[2] Ibid., p. 48

[3] S. Buxton, Finance and

Politics, 1783-1885, Vol. 1, 1888, pp. 7-8

[4] The London Times, 20 July

1803.

[5] A. Hope Jones, Income Tax

in the Napoleonic Wars, 1939, p. 74. The rate was originally set, in 1799, at two shillings for incomes above M0 with abate ments from &200 to S60; Hope-Jones p. 15.

[6] Chatham Papers (PRO), Vol.

279 (Dec. 1797), (Sept. 1798).

[7] Ibid.

[8] Extract from the Report from

the Commissioners of Inland Revenue (1870) p. 121

[9] Taken from Hope-Jones, p.

77. Upon its re-introduction in 1802 the tax was called the Property Tax but this fooled no-one and

it continued to be referred to as Income Tax.

[10] R. Hidy, House of Baring,

1949, p. 28. See also W Court, A Concise Economic History of Britain, 1969, pp. 139-150.

Back to Napoleonic Notes and Queries # 16 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1995 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com