Emmanuel de Grouchy was a member of one of the oldest

noble families in France, and this alone made his rise to high rank

after the Revolution worthy of comment. Born in 1766, Grouchy

enrolled at the age of 14, in 1781, in the artillery school in

Strasbourg, but quickly transferred to the cavalry, where he was to

serve for much of his career. By 1786, he had reached the rank of

second lieutenant in the "compagnie ecossaise", the senior unit of

the Garde du Corps - the equivalent rank to a lieutenant-colonel in

a line unit. However it may have been because of growing

sympathy with the reform movement that Grouchy took early

retirement in 1787.

Emmanuel de Grouchy was a member of one of the oldest

noble families in France, and this alone made his rise to high rank

after the Revolution worthy of comment. Born in 1766, Grouchy

enrolled at the age of 14, in 1781, in the artillery school in

Strasbourg, but quickly transferred to the cavalry, where he was to

serve for much of his career. By 1786, he had reached the rank of

second lieutenant in the "compagnie ecossaise", the senior unit of

the Garde du Corps - the equivalent rank to a lieutenant-colonel in

a line unit. However it may have been because of growing

sympathy with the reform movement that Grouchy took early

retirement in 1787.

He quickly returned to the colours after the revolution, and by 1792 he was a general of brigade. Not only did Grouchy manage to gain high rank despite his aristocratic background, perhaps even more remarkably he won the affection of his men, who mutinied at an attempt to dismiss him in 1793. By this time he had served with the Armies of the Centre and the Alps as well as against the rebels in La Vendee, and even the most fervent revolutionaries had to recognise his dedication to the cause.

By 1795, Grouchy was a general of division, and serving in Italy, where he displayed a lifelong tendency to be wounded on every possible occasion, suffering somewhere between nine and thirteen wounds during the French retreat from Novi, and being captured.

During his captivity Grouchy first came into conflict with Bonaparte, protesting at the establishment of the Consulate, but was restored to command after his release serving, this time as an infantry commander again with distinction, under Moreau at Hohenlinden in 1800. His support for Moreau after his disgrace did not endear Grouchy to Bonaparte, and his displeasure may have been shown by Grouchy being limited to the command of a division under Marmont during the Austerlitz campaign.

But Grouchy's greatest days were about to begIn; promoted to command of a division of drasoons, he led a highly effective pursuit of the Prussians after Jena, and did well at Eylau. At the latter battle he was trapped under his horse and broke a leg. He was in action again in 1807, this time at Friedland, where his apparent hesitancy in committing his cavalry against the retreating Russians was held by Napoleon to have deprived him of total victory.

In 1808, Grouchy was serving as Governor of Madrid at the time of the May Rising, which he suppressed. In 1809, he was back with the Grand Armee, serving under Davout at Wagram, and after this was made colonel general of Chasseurs. In the invasion of Russia in 1812, Grouchy led the III Corps of Reserve Cavalry under Eugene. He took part in all the major actions of the campaign, and in July made a brilliant I 00-mile raid, forcing the crossing of the Dnieper River. It is a measure of the Emperor's confidence in Grouchy, despite their political differences that during the ordeal of the retreat, he was given command of Napoleon's guard of officers - the "battalion sacre".

Grouchy had by this time been wounded some twenty three times in the course of his career, and he was unfit for action during most of 1813. However the supreme crisis of 1814 saw him back in action, most notably at the battle of Vauchamps (February l4th).

Whatever Grouchy's doubts about some of Napoleon's actions, he was uneasy under the restored Bourbons, despite being made inspector-general of chasseurs, and immediately rallied to the Emperor on his return from Elba. He suppressed Angouleme's farcical Royalist rising in the south-west in March, and on April l5th was created the last of the Napoleonic Marshals. Grouchy was given command of the reserve cavalry division of the Armee du Nord, and took part in the invasion of Belgium in June.

It is now that the most controversial phase of Grouchy's career begins. His role in the pursuit of the Prussians after Ligny, and the events leading up to the battle of Wavre, when he had been given command of the right wing have frequently been discussed, and will only be outlined briefly here. Neglected, but of considerable interest, is Grouchy's skillful retreat to Paris after the disaster at Waterloo.

Grouchy's share of responsibility for that defeat is still a

source of much controversy. He has been blamed for carrying out a

lethargic and over-cautious pursuit of the Prussians on June 17th

but part of the blame, if blame there be, for this must lie with

Napoleon. Though he did not get his troops under way til nearly

noon, Grouchy had heen pressing the Emperor for orders early in

the day, only to receive the retort: "I will give them to you when I

see fit." In any case, Vandarnme and Gerard's corps, which formed

the bulk of Grouchy's wing had suffered very heavily on the

previous day, and were in no state to cope with another major

action anyway. Furthermore, Grouchy's relations with his corps

commanders were poor, and Vandarnme at least, was arguably

unsuitable for his command.

Grouchy's share of responsibility for that defeat is still a

source of much controversy. He has been blamed for carrying out a

lethargic and over-cautious pursuit of the Prussians on June 17th

but part of the blame, if blame there be, for this must lie with

Napoleon. Though he did not get his troops under way til nearly

noon, Grouchy had heen pressing the Emperor for orders early in

the day, only to receive the retort: "I will give them to you when I

see fit." In any case, Vandarnme and Gerard's corps, which formed

the bulk of Grouchy's wing had suffered very heavily on the

previous day, and were in no state to cope with another major

action anyway. Furthermore, Grouchy's relations with his corps

commanders were poor, and Vandarnme at least, was arguably

unsuitable for his command.

The orders which Grouchy finally received were themselves open to misinterpretation. Napoleon's intention was that Grouchy should shadow the Prussians, and shepherd them eastwards, preventing them from joining up with Wellington, whilst at the same time avoiding becoming involved in a maior action, and stay close enough to the main army to be able to reinforce it if needed. These orders mig~t have inhibited a bold and selfconfident commander, and Grouchy, in his present situation, was neither of these.

Apart from any other considerations, he had had ample experience in 1814 of Blucher's propensity to turn suddenly on pursuers, and hit back savageiy. He had had little enthusiasm for the operation in the first place, suggesting to Napoleon that it was too late to catch the Prussians (which was not Napoleon s intention anyway) and that his troops would be more effective operating with the main army.

Grouchy's doubts and caution spread to his subordinates, whose men were in any case still combat weary. The result was that the pursuit was not pressed closely, and Grouchy's awareness of Prussian moves was incomplete. It seems that early on June 18th Grouchy still believed that the bulk of the Prussians were withdrawing on Liege, thougn by 6a.m., reports from his patrols caused him to report to Napoleon that Blucher was heading for Brussels via Wavre, and that he was 'starting immediately for Wavre'.

In fact, Vandamme's infantry did not begin their march unil two hours later, and at about 10-30 a.m. gained touch with the Prussian rearguard under Thielmann near the viiIage of La Baraque. Half an hour later, Groucny was breakfasting with Gerard at the village of Walklin when the sound of Napoleon's opening cannonade at Waterloo was heard. Gerard urged Grouchy to march with all or part of his force to the sound of the guns, but Grouchy refused. He has been fierceiy condemned for this, but the danger of such after the event reactions is that they credit Grouchy with much more knowledge than he actually possessed, though he may be legitimately blamed for his failure to follow up the Prussians more effectively.

Napoleon had been very reluctant to share his intentions with his subordinates, but Grouchy knew that the main army was intended to engage Wellington, therefore the sounds of gunfire might merely indicate that this pian was being carried out, and did not necessarily indicate that Grouchy was to shift from his own previously alloted role. He may have been influenced by the time factor, and memories of the way in which D'Erlon's corps had wasted the whole of June 16th marching and counter-marching between Quatre Bras and Ligny without intervening in either battle.

A more self-confident general might have taken on his own head the responsibility to deviate from the orders which he had been given, but Grouchy lacked such a belief in his own ability. Napoleon should have been aware of Grouchy's defects when he gave him his command, though lack of any more suitable candidates must have played a part. But to expect him to have acted like a Lannes or Davout, when he plainly lacked the qualities of either, is surely unfair.

The upshot, of course, wasa that Grouchy continued his march on Wavre, and by the time, at 4 p.m., that he received Napoleon s somewhat ambiguous orders of the morning, urging him both to push on towards Wavre whilst drawing closer to the main army, he was becoming entangled in fighting with Theilmann, and the chance of intervening in support of the emperor had already realistically gone.

Fighting went on until 11p.m, and both sides were ready to resume at dawn on the 19th. However by 10 a.m., Theilmann was in retreat; he was heavily outnumbered and the news of Waterloo meant that Grouchy no longer presented a long-term threat.

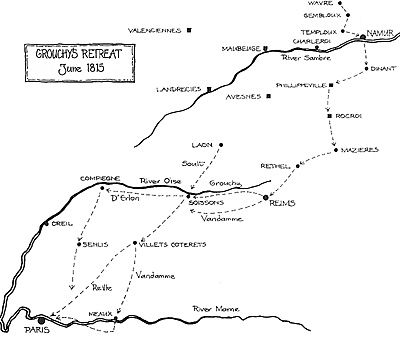

'The French had just begun to advance up the Brussels road when at about 10-30 a.m. news arrived of the disaster suffered by Napoleon. To Grouchy, the fact that he was now on his own and effectively no longer answerable to the Emperor seems to have acted as a release. Henceforward his movements and orders display a decisiveness which had hitherto been conspicuously lacking. His options were unenviable; with only 30,000 men, he could hardly continue his advance into the rear of the victorious Allies. Vandamme indeed proposed a rapid descent on Brussels, to free any prisoners of war who might be there, followed by a retreat to Lille via Enghein and Ath. Grouchy wisely rejected such a dangerous and ultimately futile scheme. Instead he would fall back on Namur, thus avoiding becoming entangled with Napoleon's routed forces.

Grouchy's force was still in considerable danger; there was a brief possibility that the Prussian II corps (Pirch I) might be able to cut off Grouchy's retreat to the Sambre, but fortunately Pirch's men were too exhausted to carry out these orders. Moving fast, Exelman's cavalry reached Namur, covering the 30 miles along muddy lanes in five hours, and secured the bridges over the Sambre for Grouchy's retreat.

By nightfall, Gerard's corps had reached Temploux on the Nivelles-Namur road, and were joined there at 11p.m. by Vandamme. The rearguard, consisting of Pajol's cavalry and Teste's infantry division, demonstrated against Thielemann to keep him occupied until the main force was clear, and itself halted for the night at Gembloux.

Pirch, meanwhile, was at Mellery, about 8 miles behind Grouchy's starting point at Wavre, and, even if he had been unable to cut off his retreat, might have threatened his right flank and delayed the withdrawal, but the Prussian commander was unwilling to move without news of Theilemann, whilst the latter did not learn of Grouchy's retreat until the next day.

As a result, Gerard's Corps, bringing up the French rear, were able to beat off some attacks by Theilemann's cavalry near Temploux, and Grouchy's main force was able to cross the Sambre at Namur and head for Dinant. Teste's division was left in Namur to delay pursuit, and despite the fact that it numbered only about 2,000 men, with eight guns, and lacked adequate defences, skillfully held off the half-hearted probes of Pirch's 20,000 men, and, covered by burning barricades on the main bridge over the Sambre, successully withdrew at nightfall, rejoining Grouchy at Dinant.

From here, on June 21st, the whole force marched on Phillippeville, delaying any pursuit by placing barricades across the roads.

Grouchy's aim now was to join the other remnants of the Armee du Nord which Soult was mustering around Laon, and then fall back on Paris, his retreat covered by the frontier fortresses which still held out. Blucher's plan was to reach Paris before the remains of the French army, and he was aided in this by the weak resistance put up by many of the frontier garrisons. Whereas the Prussians could advance directly on the French capital, Grouchy would have to make a long detour in order to avoid being cut off. Fortunately, Blucher advanced cautiously, but the race would be desperately close. I

Both sides raced for the crossings of the River Oise. On June 25th, Grouchy, at Soissons, took over command of the remnants of the Armee du Nord from Soult, and despatched 4,000 men under d'Erlon to secure the bridge at Compiegne, and block the Prussians from crossing to the southern bank of the Oise. They were narrowly beaten there by a division of Ziethen's corps, and repulsed, though the Prussians were too exhaused to pursue.

Though he had failed to hold the Oise, d'Erlon was now ahead of the Prussians in the race for Paris, and during June 27th, the Prussians were delayed further in skirmishes at Creil and Senlis, where, although the Prussians had the best of the fighting, the French gained further time for their three main retreating columns under Reille, d'Erlon and Vandamme to press on towards Paris.

At dawn on June 28th, the 2nd Division of Zieten's corps was approaching Grouchy's headquarters at Villers Cotterets. They believed the town to be weakly held, but in fact Grouchy had 9,000 men ready to meet their attack. The Prussians were soundly repulsed, and then the French, fearing their retreat was about to be cut off, panicked, and fled down the road to Meaux. However, the check inflicted on the Prussians was sufficient to allow Grouchy to bring his troops safely into Paris on June 29th.

Though in the event Grouchy's arrival did nothing to prolong French resistance, he had at least saved much of the army, and redeemed some of his own reputation in the process. Very much persona non grata with the restored Bourbons, Grouchy took refuge in the United States until 1820, when he was able to return to France. Cast by the Bonapartists in the role of scapegoat for the defeat at Waterloo, Grouchy defended himself with more zeal than dignity, and even the restoration of his baton by Loius Philippe in 1831 did little to rehabilitate his reputation. Grouchy died in 1847.

Though by no means the main culprit for Napoleon's defeat in 1815, Grouchy had certainly proved ill-suited for the role which he had been given. Though the suggestion which has been made that Grouchy was a more able leader than Murat is exaggerated so far as command in battle is concerned, he was certainly a highly competent all-round commander of cavalry, who deserves a higher rating than history usually affords him.

Further Reading

D.G. Chandler (ed),' Napoleon's Marshals", 1987.

D.G. Chandler, 'Waterloo, the Hundred Days', 1980.

W. Hyde Kelly, 'The Battle of Wavre and Grouchy's Retreat", 1905 (reprinted 1993).

Back to Napoleonic Notes and Queries # 15 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1994 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com