Part 1: The Portuguese Army in the Peninsula War

Despite his success Wellington was unable to stop the French at Bussaco and he withdrew to the safety of the Lines of Torres Vedras. So formidable were the forts and redoubts of the Lines, Massena refused to attack them with the force under his command. He sent an appeal to Napoleon for reinforcements and Massena settled down before the Lines to wait. The Lines were manned by the Ordenanza and the militia! leaving the field army free to manoeuvre on any threatened point. The divisions of the militia and Ordenanza of the northern provinces were allowed to remain in detached bodies the whole being commanded by the Portuguese General Bacellar, with the individual divisions operating semi-independently under the BrigadierGenerals Silveira and Millar. and Colonels Trant and Wilson. In the country districts outside the Lines these Portuguese irregular restricted the movements of the French army by attacking foraging parties and blocking all lines of communication. During this period Robert Long, a British cavalry general arrived in the Peninsula and saw the Portuguese for the first time. "The appearance of the Portuguese Troops has really astonished me." He wrote. "It is in every respect equal to our own, and in some instances finer and their conduct 6 hitherto before the Enemy has commanded the most decided approbation."

Despite his success Wellington was unable to stop the French at Bussaco and he withdrew to the safety of the Lines of Torres Vedras. So formidable were the forts and redoubts of the Lines, Massena refused to attack them with the force under his command. He sent an appeal to Napoleon for reinforcements and Massena settled down before the Lines to wait. The Lines were manned by the Ordenanza and the militia! leaving the field army free to manoeuvre on any threatened point. The divisions of the militia and Ordenanza of the northern provinces were allowed to remain in detached bodies the whole being commanded by the Portuguese General Bacellar, with the individual divisions operating semi-independently under the BrigadierGenerals Silveira and Millar. and Colonels Trant and Wilson. In the country districts outside the Lines these Portuguese irregular restricted the movements of the French army by attacking foraging parties and blocking all lines of communication. During this period Robert Long, a British cavalry general arrived in the Peninsula and saw the Portuguese for the first time. "The appearance of the Portuguese Troops has really astonished me." He wrote. "It is in every respect equal to our own, and in some instances finer and their conduct 6 hitherto before the Enemy has commanded the most decided approbation."

Massena failed to receive the reinforcements he required and he retreated back towards Spain. Wellington followed up the retreating French army which remained around the frontier near Almeida, sending part of his force under Beresford to the south to re-take the stategically important fortress of Badajoz which had just fallen to the French army of Marshal Soult. Some ten miles before Badajoz was the fortified town of Campo Mayor which had been captured by a small force under General Latour-Maubourg. At the approach of Beresford's 18,000 Anglo-Portuguese, LatourMaubourg ordered the evacuation of the town. In the advance of Beresford's corps was a brigade of light cavalry consisting of the l3th Light Dragoons and five squadrons from the 1st and 7th Portuguese regiments commanded by General Long.

Long decided to attack the French before they escaped. He ordered the l3th Light Dragoons to charge the French rearguard. They crashed into the French 26th Dragoons driving them back upon the second French line of the 2nd and 10th Hussars. The two squadrons of the 7th Portuguese charged in support of the Light dragoons and the French broke and fled with the allied cavalry racing behind them. Long found himself facing the rest of Latour-Maubourg's force with just the three squadrons of the 1st Portuguese. Long ordered the Portuguese cavalry to advance but. as at Vimeiro, upon coming under fire from a battalion of French infantry the Portuguese turned and fled. The French escaped without further molestation.

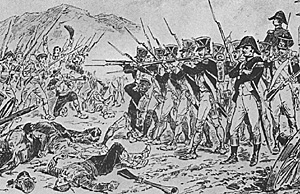

Beresford laid siege to Badajoz but Soult was not prepared to abandon the fortress without a fight and he marched to relieve the city with an army of over 23.000 men. The opposing forces met at Albuera. The battle was a confused affair with Beresford losing control of events. As the crisis of the battle approached, General Cole, with the 4th Division, advanced upon the French flank. Cole ordered his regiments into line with one unit in column on either wing. Upon seeing this long line of bayonets Soult launched his cavalry at the right of the 4th Division where Harvey's Portuguese brigade (Ilth and 3rd Line and the 1st battalion Lusitanian Legion) was posted. Four regiments of dragoons bore down upon Harvey's Brigade but the Portuguese stood absolutely steady and delivered a series of volleys which completely broke the charge of the dragoons. Cole was able to press home his attack without further fear of the French cavalry. With the battle almost won Beresford brought up three Portuguese brigades in line - those of Collins, Foneseca and Harvey - and the French attack was finally driven off.

In the north of the country Massena, like Soult, had tried to relieve a fortress, that of Almeida. He too had met defeat at the Battle of Fuentes d'Onoro. The Portuguese troops had not been heavily engaged and had lost only 25 men. But the Portuguese ranks were severely depleted caused by the inadequate way in which the Portuguese government supplied and fed its troops and the slowness with which convalescents and re- cruits; were sent from the hospitals and depots to the front. As a consequence some of the infantry regiments could only field 500 or 600 men and the entire force of twenty-five battalions totalled no more than 11,000 even though they had numbered 13.000 the previous winter. The only cavalry regiment with the northern army now had only 312 men in the saddle whereas previously it had numbered almost 500. The men were still present but the horses had been lost due to poor horse-care by the men and a lack of supervision by the officers.28

Britain had agreed to pay for 20,000 Portuguese troops yet the responsibility of feeding them still Jay with the Portuguese authorities. The Portuguese Commissariat was divided into two departments, one being responsible for the supply of provisions, the other with the transport. The former, the junta da direccao geral dos provinsentos das mnuicoes de boca para o exerito had Intendants in every province and storekeepers, or Feitors; in every town. The method of supply was that the Portuguese government contracted with the junta for the different kinds of provisions and forage at a fixed price and the Feitors were then directed to purchase on the spot what was required at the cheapest possible price. The impecunious farmers could not afford to sell their products at such low prices and consequently they offered as little as they could to the army, hiding the rest. What food the army did manage to acquire whether by purchase or simply by seizing what it could find, was paid for in government bills which were regarded as worthless.

As a result the troops were half-starved and sickness and desertion were common: "the Portuguese army could not be in the distress under which it suffers from want of provisions," wrote Wellington, "if only a part of the food it receives from the country were paid for."29 This would be a recurrent complaint in Wellington's dispatches throughout the war.

The Portuguese artillery, in contrast to the other arms, was still relatively strong. There were four artillery regiments, those of Lisbon, Estremoz, Algarve and Porto. Each consisted of seven companies of gunners, one of bombadiers one of sappers and one of miners with a theoretical combined strength of 1,000 men per regiment. The Artillery was principally employed in the numerous fortresses throughout the kingdom and the men were taken as required to form the crews for the field batteries. Apart from the two artillery brigades with Beresford there were five batteries with Wellington in the north. Two of these were nominally from the 2nd Regiment brigaded together under Major Arentschildt and were attached to the 3rd Division. Another battery also from the 2nd Regiment, was with Pack's Portuguese Brigade. One battery from the 1st Regiment was attached to the 5th Division and one other from the 1st Regiment was with the 6th Division. The artillery played an important part in the sieges of Ciudad Rodrigo and Badajoz.

Altogether 400 officers and men of the Portuguese artillery manned the breaching guns at Ciudad Rodrigo. Johnny Kincaid, a British Rifles officer watched one of the Portuguese batteries in action at Badajoz. "The Portuguese artillery under British officers was uncommonly good. I used to be much amused in looking at a twelvegun breaching battery of theirs. They knew the position of all the enemy's guns which could bear upon them and they had one man posted to watch them to give notice of what was coming, whether a shot or shell, who accordingly kept calling out "Bomba, balla, balla, bomba!" and they ducked their heads until the missile passed but sometimes he would see a general discharge from all arms, when he threw himself down, screaming out, "Todostodos!" meaning everything". 30

In the assault's upon Ciudad Rodrigo and Badajoz the Portuguese were assigned secondary roles. At Ciudad Rodrigo Pack's Brigade was ordered to make a diversionary raid upon the outwork in front of the Santiago Gate on the south-eastern side of the town and O'Toole's battalion of the 2nd Cacadores was to attack the bridge over the River Agueda. Similarly, at Badajoz Power's Brigade was to make a diversionary attack upon the bridgehead on the south bank of the Guiadiana.

Marshall William Carr Viscount Beresford

Marshall William Carr Viscount Beresford

After his capture of these two key fortresses Wellington advanced into Spain and clashed at Salamanca with Marshal Marmont who had superceded Massena in command of "l'Armee de Portugal". After a period of moves and countermoves Wellington ordered Pakenham's 3rd Division to charge the head of the French column. Pakenham advanced with D'Urban's cavalry covering his right flank. D'Urban himself galloped ahead of the division and he saw a French battalion marching across the British front. He decided to attack without delay, and he wheeled his leading regiment - the 1st Portuguese - into line and ordered them to charge the battalion before it could form square. Although only numbering a little more than 200 sabres the 1st charged straight into the tightly packed French column, supported by the 11th Portuguese and two squadrons of the l4th British Light Dragoons. The battalion was completely smashed, with the Portuguese taking many of the survivors prisoner.

The allied attack against the centre of the main French line was undertaken by the 4th and 5th Divisions. Leading Cole's 4th Division into action was Stubb's Portuguese Brigade of the 11th and 23rd Line with the 7th Cacadores in front. Stubbs attacked the French regiment ahead of him driving it back upon its parent body clearing the way for Coles assault upon Clausel's Division. Brigadier-General Pack, who had been given a discretionary role by Wellington, chose to mount the greater Arapile and attack the French division on the heights to stop it descending upon the flank of the advancing 4th Division. He deployed the 4th Cacadores as a skirmish line with the four Grenadier companies from his Line regiments in support, and behind in two columns the 1st Line on the right and the 16th on the left. The Cacadores led the way up the centre of the Arapile, pushing back a thin screen of voltigeurs. The Cacadores climbed almost to the crest of the ridge only to find their path obstructed by a high bank. The men stung their rifles over their shoulders and began scaling the obstacle. It was at this moment that the French 120th Regiment, which had been waiting on top of the ridge released a crashing volley and charged the helpless Cacadores. The French broke through the riflemen and the Grenadiers and smashed into the rest of the brigade which was halfway up the slope. The brigade lost 38 men in ten minutes.31

Further Disasters

Further disasters to the Portuguese were soon to follow. The French brigade on the Greater Arapile, having beaten off Pack, moved against the 4th Division. Only a battalion of the 7th Cacadores, which Cole had detached as a covering force, stood in the way of the French force and the 4th Division's exposed flank. The Cacadores stood their ground as the three French regiments converged upon them 32 but they were overwhelmed by superior numbers of the enemy. Clausel, having taken over command from the wounded Marmont, decided to follow up the reverses suffered by Pack and Cole and he sent his Dragoons against Stubb's Brigade, inflicting heavy losses upon the Portuguese until the 11th Line formed square and beat off the French cavalry. Wellington now brought up his reserves to counter Clausel's attack. The advance of Clausel's own division was halted by Beresford who took Spry's Brigade (3rd and 15th Line th Cacadores) and fell upon the French flank, Clausel's Division had to stop its march and wheel round and face Spry, allowing the 5th and 6th Divisions to complete Clausel's defeat.

The French began to withdraw with Ferey's Division covering the retreat. The 6th Division was given the task of engaging the French rear-guard which was drawn up in line with a wood in its rear. In the front line of the 6th Division was Rezende's Brigade consisting of the 8th and 12th Line and the 9th Cacadores. The five battalions deployed and advanced upon the French line: "we saw the enemy marching against us in two lines," wrote a French officer in Ferey's corps, "the first of which was composed of Portuguese. Our position was critical, but we waited for the shock: the two lines moved up towards us; their order was so regular that in the Portuguese regiment in front of us we could see the company intervals, and the officers behind keeping the men in accurate line, by blows with the flat of their swords or their canes. We fired first the moment that they got within range: and the volleys which we delivered from our two first ranks were so heavy and so continuous that, though they tried to give us. back for fire, the whole melted away."33

Rezende's Brigade lost 487 men in the fifteen minutes that it had been engaged, more than any other Portuguese brigade.34

The French defeat at Salamanca caused them to abandon Madrid and Wellington made a triumphal entry into the Spanish capital. On the approach to Madrid, D'Urban's Brigade formed the van of the AngloPortuguese cavalry. 'Urban pushed back the French outpost line composed of the l3th and l8th Dragoons reaching the town of Ma,ialahonda on the morning of 11th August 1812. D'Urban ordered his men to cook their midday meal and to wait until later in the day before continuing their advance. Just before 16.00 hours, six regiments of French cavalry, some 2000 men, appeared before Majalahonda. Outnumbered almost three to one D'Urban should have fallen back upon the rest of the allied cavalry, But the performance of his brigade at Salamanca encouraged him to attempt to fight the French dragoons and lancers. Whilst messengers were sent to bring up the rest of the Anglo-Portuguese advance guard, D'Urban deployed the 1st and 12th regiments into line, threw one squadron of the 11th out in skirmish order, and placed the other squadron of the 11th in reserve. The opposing lines of cavalry drew sabres and charged but when they were only a few yards from the French the Portuguese stopped turned and galloped away leaving D'Urban and the colonel's of the 1st and 12th regiments in the very midst of the enemy. The two colonels were severely wounded and captured, D'Urban managing to cut his way free and escape.

A troop of K.G.L. Dragoons and a detachment of horse artillery which had come up in support were left stranded by the flight of the Portuguese and were completely overrun. The Germans were cut to pieces and three guns were taken. Wellington was not impressed, "the occurrences of the 22nd of July (the Battle of Salamanca) had induced me to hope that the Portuguese dragoons would have conducted themselves better, or I should not have placed them at the outposts of the army. I shall not place them again in situations in which by their misconduct they can influence the safety of other troops."35

Following the Battle of Vitoria the French retreated to the Pyrenees. The Portuguese, Wellington asserted, were fighting better than ever but their numbers were sadly diminished. Some battalions were down to less than 300 bayonets, many others no more than 350. The losses suffered throughout the recent campaigns had not been replaced. Now that the fighting had moved so far away from the frontiers of Portugal the Regency was showing a marked lack of enthusiasm for the war. The recruiting laws had been allowed to lapse and those men that had been assembled at the depots were no longer being sent to the front,

In September 1813 Wellington sent Beresford back to Lisbon to expedite affairs. A number of factors contributed to the Regency's reluctance to continue supporting the war effort. The first was that as the fighting moved further north so Wellington changed his base of operations from Lisbon to Bilbao and Santander and this had drastically reduced the Regency's revenues. The second reason was that the Portuguese, as always, were worried about the Spaniards. The Portuguese had only two Line regiments, the few companies of Invalid artillery, and the militia within its borders whereas the Spaniards had large armies still under arms and no longer involved in the fighting. Unrealistic though this may seem, it must be remembered that the Spaniards had invaded Portugal twice since the end of the 18th Century and their fears were not entirely unfounded. It was also stated that Wellington had failed to give due credit to the Portuguese troops in his recent dispatches, favouring instead the less significant contribution made by the Spanish regiments attached to the allied army.

National Army

To remedy this the Portuguese Secretary at War suggested that the Portuguese regiments should be brought together under a Portuguese general to form a national army. Wellington would have nothing to do with such a proposition "separated from ourselves they could not keep the field in a respectable state, even if the Portuguese were to incur ten times the expense they now incur ... Not only can they acquire no honour in, but they cannot come out of, the contest, without dishonour."36 Throughout the Pyrenean campaign the Portuguese continued to aquit themselves admirably and Wellington took care to recognise their efforts in his dispatches.

With Napoleon's abdication and the armistice in 1814 the AngloPortuguese army was broken up. For five years they had fought sideby-side and the parting was not without tears. So successful had been the partnership Wellington applied for a Portuguese contingent to join him for the Waterloo campaign but before the arrangements had been made Napoleon had been defeated.

Because so many of the Portuguese brigades were integrated with the British brigades it is difficult to analyse their true capabilities. George Bell, an officer in the 34th Foot, wrote that: "The Portuguese army was always well and gallantly led, fought well, and ranked next to the English troops in all ways."37 In his notes on the Battle of Vitoria, however. he qualified this praise by stating: "in fact the red-coats were always expected to do the real fighting business."38 Leith Hay another British officer whilst noting the "very unsoldierlike conduct" of the Portuguese cavalry, remarked "I do it without the slightest intention of casting any reflection that can generally to the troop of that service. I have previously stated my humble tribute of respect for their undeviating good conduct on every occasion wherein I had opportunities of witnessing their demeaner in contact with the enemy."39 And from the ranks of the enemy the Baron de Marbot described the Portuguese as "the equal of British troops."40

Possibly a more realistic view of the capabilities of the Portuguese is revealed in John Golbourne's description of the Light Division's attack upon the Mouiz works on the Leser Rhune at the Battle of the Nivelle in November 1813. The assault was to be opened by the 95th Rifles with the 52nd delivering the main attack. The 1st and 3rd Cacadores were in support. Snodgrass the commanding officer of the 3rd Cacadores, however asked for his battalion to be allowed to lead the attack because if the Portuguese were beaten back the British troops would still continue the assault, but if the British attacked first and failed the Portuguese would abandon the attempt.41

NOTES

25. Lecor's Division, Militia Regiments of Santarem, Idanha, Castello, Branco,

Covilhao, and Feira, and the 12th Line Regiment = 3,829

Militia Regiments of Lisbon Thomar and Torres Vedras 1,907

Embodied Ordenanza = 761

Militia Regiments of Lisbon('E) Lisbon(W)

Setubal. and Alcacer do Sul = 2,231

Militia Regiment of Viseu = 691

Militia artillery = 2,886

Total = 11092

26. R Long, Peninsular Cavalry General, pp.68-9.

27. The Portuguese troops at Albuera:

- INFANTRY

Harvey's Brigade

- 11th Line 1,154

23rd Line 1,201

Lusitanian Legion 572

Collin's Brigade

- 5th Line 985

5th Cacadores 400

Campbell's Brigade

- 4th Line 1,271

10th Line 1,119

Fonseca's Brigade

2nd Line 1.225

14th Line 1,204

CAVALRY

- 1st Regiment 327

7th Regiment 314

5th Regiment 104

8th Regiment 104

ARTILLERY

- Arriaga and Braun's Brigades 221

28.Wellington's Dispatches vol.2, p.511-12, 516-7.

29. Oman vol.2. p. 177.

30. J.Kincaid Adventures in the Rifle Brigade p.84.

31. Oman. vol 5, p.457.

32. Oman. vol.5, p.457. says the French 11 8th Line Regiment claim to have captured a Portuguese flag which he believed was that of the 7th Cacadores. However, the 7th Cacadores were not issued with colours until after the Battle of Vitoria.

33. Lemonnier-Delafosse Campagnes de 1810 a 1815 pp.161-2 quoted in Oman vol.5, pp.464-5.

34. Portuguese troops at Salamanca:

| CAVALRY | Officers | Men | Casualties |

|---|---|---|---|

| D'Urban's Brigade | |||

| 1st and 11th Regmts. | 32 | 450 | 37 |

| INFANTRY | Officers | Men | Casualties |

| Power's Brigade | |||

| 9th and 21st Line 12th Cacadores | 90 | 2107 | 76 |

| Stubbs Brigade | |||

| 11th and 3rd Line 7th Cacadores | 137 | 2417 | 476 |

| Spry's Brigade | |||

| 3rd and 15th Line 8th Cacadores | 156 | 2149 | 123 |

| Rezende's Brigade | |||

| 8th and 1st Line 9th Cacadores | 134 | 2497 | 487 |

| Collins'Brigade | |||

| 7th and 19th Line 2nd Cacadores | 132 | 2036 | 17 |

| Pack's Brigade | |||

| 1st and 11th Line, 4th Cacadores | 85 | 2520 | 37 |

| Bradford's Brigade | |||

| 13th and 14th Line. 5th Cacadores | 112 | 1782 | 17 |

| Light Division | |||

| 1st and 3rd Cacadores | 30 | 1037 | 17 |

| ARTILLERY | Officers | Men | Casualties |

| Arriaga's brigade | 4 | 110 | 1 |

35. Wellington's Dispatches. vol.9, p.354.

36. ibid. vol.11, p. 185.

37. G Bell Soldiers Glory p. 101.

38. ibid p.71.

39 A. Leith Hay? A Narrative of the Peninsular War, vol.2 p.189

40 Memoirs du General Baron de Marbot vol. I p.485.

41 . Life and Letters of Lord Seaton p. 192.

Back to Napoleonic Notes and Queries #13 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1993 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com