Although the Russian Campaign of 1812 was immense, both in terms of d1stance and in the number of troops involved, the activities of outposts and advance guards have always been the small change of war. The brigade level action at Kobryn was not representative of the campaign, and with a bit of tweaking could make the basis for an evening's wargaming with the armies of one's choice.

After its less than glorious participation in the Austrian War of 1809 (but see With Eagles to Glory by Jack Gill, Greenhill Books 1992 for a useful corrective to many myths), the Saxon Army returned to barracks to undergo a thorough overhaul of officers, men and equipment, and re-training to make it fit enough to be included in a future Grande Armee. The need for rebuilding meant that the army was not called upon to supply units for service in the Iberian Peninsula, although the knowledge that the Saxons were staunch Catholics may also have helped. By early 1812, the Inspectors considered the revitalised army was fit for active service, and it was therefore called up for the invasion of Russia.

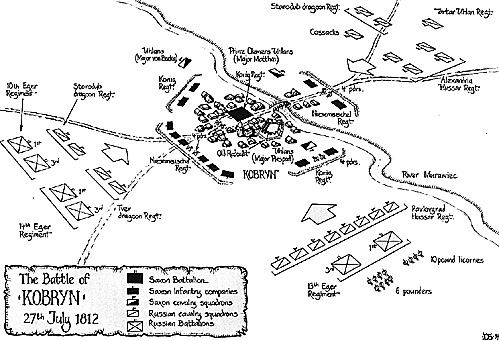

The Saxon Army supplied all of VII Corps d'Armee under General de Division Reynier, as well as a heavy cavalry brigade to IV Heavy Cavalry Corps operating with the main army. VII Corps, cons1sting of two infantry divisions and a light cavalry brigade, with 6 artillery companies as well as regimental pieces, was stationed on Napoleon's strategic right (South) flank along with the Austrian Hilfskorps under Schwarzenberg, with the intention of advancing parallel with the main army but south of the Pripet Marshes, in order to protect the main advance from the still-forming Russian 3rd West Army under Tormassov. The campaign opened on 28 June, and by 15 July VII Corps had reached Kleck. Underestimating the strength of 3rd West Army, Napoleon called the Austrians north to reinforce the main army, replacing them with the Saxons who took a sidestep to the right. Reynier took up a position at Chomsk, throwing out part of Klengel's brigade, together with three squadrons of the Prinz Clemens Uhlans to act as advance guard in the small village of Kobryn some few miles to the south. Unfortunately, Tormassov was in much greater strength than was realised, and was moving north in order to co-operate with the 1st and 2nd West Armies falling back on Smolensk.

The small village of Kobryn lay athwart the Murawiec river, where the Dvina-Pruszany and Brest-Pinsk roads crossed. The main part of the village lay on the southern (Russian) bank, and there were only a few houses on the northern. The two halves of the village were joined by a wooden bridge. Nearly all the buildings were of wooden, light, construction, and the only substantial one was a small clo1stered church, close to which was an old redoubt from the Great Northern War of a century before. Whilst some attempt would likely have been made to occupy this, because it was surrounded by houses any fields of fire were very restricted. The surrounding countryside was flat and open. All in all, the position did not have a great deal to recommend it, and one can only assume that Reynier intended the force to act as a trip wire to give him time to react with the rest of the Corps and seek help from Schwarzenberg if necessary.

The Saxon defence positions were barricaded, and cons1sted of the following:

To the north:

2 companies of the Nieserneuschel regiment, together with two 4 pounders of the regimental artillery company and a squadron of the Prinz Clemens Uhlans under Major Matthai.

To the south west:

2 companies of the Konig regiment, with a squadron of the Uhlans under Major von Becka further out.

To the south:

the remaining 6 companies of the Nieserneuschel regiment, probably with the last two guns of the regimental artillery company.

To the east:

2 companies of the Konig regiment, with 2 4 pounders of the regimental artillery company, and with a third squadron of the Uhlans under Major Piesport.

In the market square:

A battalion of the Konig regiment, with the remaining 2 guns of the regimental artillery company.

Overall, the strength of the defenders was:

The four infantry battalions 2038 officers and men

The two regimental artillery companies 125 officers and men

The three squadrons of Uhlans 270 officers and men

Total 2433 officers and men

Advancing against them were the Russian forces:

From the north:

2 squadrons of the Alexandria Hussar Regiment, supported by a sotnia of Cossacks. Behind them were an additional 2 squadrons of the Alexandria Hussars, 2 squadrons of the Starodub Dragoon Regiment, and I squadron of the Tartar Uhlan Regiment.

From the east:

8 squadrons of the Pavlovgrad Hussar Regiment, the 1st and 3rd battalions of the 13 Eger Regiment and a company of artillery, probably a horse company, cons1sting of eight 6 pounders and four 10 pound licornes.

From the south:

2 squadrons each of the Starodub and Tver Dragoon regiments together with the 1st and 3rd battalions of the 10th and l4th Eger Regiments.

Von Pivka gives the Russian strength as some 12,000 men with 12 guns, which seems high. Based on an average strength, and remembering that whilst these units had not yet fought against the French, they were re-deploying from the Turkish front, I would suggest that the force cons1sted of some 3,500 infantry, 1,900 regular cavalry and 300 cossacks.

Since Tormassov was approaching from the west, it is evident from the above dispositions that he had been able to turn the Saxon position to get a sizable portion of his force behind the town to act as an anvil against which to push Mengel. However, the whole of the perimeter was under attack, so that Mengel could not have the luxury of shifting unattacked forces to critical areas. In addition, Tormassov was able to pass units over the shallow river from the Brest road to communicate With his northern front if necessary.

With artillery superiority, Tormassov was quickly able to move up to the outskirts of the town, forcing the defenders back. Realizing that,the position was rapidly becoming untenable, Mengel ordered Colonel Zechwitz, who had accompanied the Prinz Clemens Uhlans, to concentrate his squadrons and try and cut his way out through the weakest part of the Russian cordon to the north. This action was successful and the Uhlans were able to make contact with Reynier's relieving force later that day.

Back in Kobryn, the Saxons were being forced back into the centre of the town. The Konig reserve battalion took up a position in the redoubt where the Russian cavalry was of no use, and where all the Saxon units were soon concentrated in the hope that they could hold out long enough for Reynier to arrive. This hope was quickly dashed, for the Russian assaults had used up much of the defender's ammunition, and their supply train had been captured by cossacks earlier. As can be seen from the casualties, the Saxons had been able to beat off several attacks, but numbers and fatigue were beginning to tell, and eventually the Russians were able to launch an attack that could not be held, and Mengel was forced to capitulate.

Saxon casualties were between 273 (Nafziger) and 286 (vonn Pivka) killed and wounded, and 2054 men, 8 guns (Nafziger says 4) and 4 flags captured. No doubt some of the captured troops took the chance to join the Russo-German Legion later, but the question of how many men actually got home is open to debate. The Russians lost about 600 men, and I would suggest that the vast proportion of these fell amongst the six Eger battalions, a casualty rate of perhaps 10%.

Wargaming Kobryn

The idea of gaming a lost cause tends not to find many takers, but by building a scenario that depends on the Russians getting their forces on the table to co-ordinate their attacks, failure in which could allow the Saxons either to defeat the prongs in detail, or to escape could make it more of an option. Details of the available forces are shown above. Readers will observe that the Grenadier Battalion von Brause (Regiments Konig and von Nieserneuschel) which formed part of the brigade is missing form the orbat. I can think of no good reason why the unit was detached, and one would be forgiven if one thought that a m1stake had been made in the sources. However, since the unit is mentioned as fighting during the retreat later, one can only assume that the senior commanders preferred to keep such a high value asset concentrated. Players who feel that the game is too one sided however, are at liberty to include it in the refight. The unit numbered 709 officers and men on June 30, and probably numbered some 520 men on 27 July assuming average losses to date. The Grenadier battalions did not have artillery companies.

The Saxons start the game in the town, and the Russian player(s) decide how their forces are going to be deployed and where. They then dice to see on what move they appear on the road entrance. As soon as the first Russian force is deployed, the Saxon defender can split his force up, and deploy where he wishes, provided that it is more than a charge move from any road exit. The remaining Russian forces appear as indicated by their die roll. There is of course no reason why the Saxon cannot try to escape, but I would suggest that the town should be in the centre of the table to give him a long march if he elects to do so. If players build in points values for casualties and escaping troops, the game promises to be a good evening's entertainment.

The scenario also lends itself to revamping by changing time, place and participants, such as a French defence against Freikorps in 1813 etc, but if you decide to transplant it to the Peninsular with the Spanish as attackers, you will probably need to replace most of the cavalry with guerillas, since the Spanish did not have a large mounted arm.

Bibliography

NAFZIGER, George Napoleon's Invasion of Russia, Presidio 1988

NAFZIGER, George with DEVOE, Tom & WESOLOWSKI, Mariusz Poles and Saxons of the Napoleonic Wars, Emperor's Press 1991

NAFZIGER, George The Russian Army, RAFM, 1983 von PIVKA, Otto Armies of 1812, Vol 1, Patrick Stevens Ltd, 1977

von PIVKA, Otto Napoleon's German Allies (3): Saxony 1806-1815, Osprey, 1979

Back to Napoleonic Notes and Queries #13 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1993 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com