A joke, said to be of First World War vintage, but undoubtedly much older, poses the question;

- "What's a soldier for, Dad?"

"To hang things on, son."

The modern British soldier is blessed with a single complete set of straps, belts, packs and pouches, all carefully designed by 'experts' to enable him to carry all the food, water, ammunition, clothing, tools and personal effects he might just possibly require to fight the next Thirty Years War. [Personally, I used to discard the lot, stuff what I could in my pockets, and carry the expendable items in an old sandbag, but that's neither here nor there]. Descriptions of 18th century and Napoleonic foot soldiers lay great stress on the weight of equipment which they were expected to carry, with a clear implication that in those bad old days the poor dears were severely overloaded. A modern British infantryman is unlikely to be much impressed.

The 18th century British soldier received three quite separate collections of equipment:

First came his accoutrements. These comprised a broad buff leather belt and a cartridge box slung over one shoulder, and a second belt worn either around the waist or across the other shoulder, which carried his bayonet and in the early part of the period a sword as well. These accoutrements were procured regimentally according to officially approved patterns, issued to the soldier and recovered from him at the end of his service.

Then came the knapsack. This was a necessary' and again contracted for regimentally, but this time it was paid for by the soldier himself, on enlistment, through a hefty stoppage from his bounty, and thereafter allowed to be his personal property.

Thirdly came 'camp equipage'. This, as the term implies was actually supplied by the Board of Ordnance, or sometimes directly by a contractor working to the Board's order, only when a battalion was ordered on actual service. Camp equipage covered a multitude of sins, but as far as the individual soldier was concerned, he received a canteen - generally a tin one throughout the period in question - and a large linen haversack supposedly for carrying his rations.

Few of these items survive and by the very nature of the procurement process, few specifications, except for the accoutrements, survive either. Consequently we are very largely thrown on the mercy of contemporary artists. This is satisfactory enough when it comes to looking at accoutrements and camp equipage; being slung at the soldier's side these are generally well enough illustrated. Knapsacks, unfortunately, are a different matter altogether.

It is a truth universally acknowledged that an artist commonly finds his subject's face to be infinitely more interesting than his backside. Consequently, very few contemporary illustrations show knapsacks in any detail and as a result some very dubious reconstructions - often erroneously based upon continental examples - have been offered to an eager public in general and to re-enactors in particular.

During the 18th Century three quite distinct styles of knapsack can be observed in the British service, besides what looks as if it might be a transitional one:

- 1. The duffle-bag

2. The square goatskin bag

3. The folded canvas envelope

The first of these was indeed no more than a tubular sack, slung diagonally across the soldier's back by means of a narrow leather strap and secured at its mouth by a drawstring. Some modern illustrations and reconstructions (probably influenced by German and other continental examples] depict it as a satchel, but the true nature of the 'sausage bag' is very clearly shown in at least three illustrations; a water colour by Sandby of 1746, one of Morier's grenadier paintings of c1748, and a painting by Edward Penny showing the Marquis of Granby giving a sixpence (or perhaps even a shilling) to a sick soldier. Both Morier's and Penny's paintings show that the bag was made of hairy cowhide, but otherwise the form of the knapsack appears not to have changed in any great way since the Great Civil War of the 1640s.

At round about pretty much the same time that Penny was showing Granby to be such a damn fine fellow, a radical alteration was taking place in the form of the knapsack.

The earliest illustration of the new style appears to be a Sandby sketch from the 1760s showing some kind of a knapsack worn square on the soldier's back with narrow straps looped round both shoulders in the manner now regarded as normal and indeed natural for all packs and rucksacks. It would be interesting to know to which regiment the soldier belonged, for this mode of carrying the knapsack is generally thought to have been brought back to Europe by both the British and French, who'd picked up the idea from the North American Indians. Unfortunately, by its nature Sandby's sketch is more impressionistic than precise, but it seems nevertheless to depict something not at all unlike a a Board of Ordnance haversack worn on the back rather than on the hip.At any rate the the flapped top secured by a couple of buttons can be seen quite clearly although it is equally obvious from the sketch that it is made of cowhide rather than linen and can therefore be accounted a proper knapsack and perhaps a precursor of the square goatskin one.

Curiously, during the subsequent American War, a number of rebel units perforce used linen haversacks worn square on the back in lieu of more substantial knapsacks, so it is possible that the style depicted by Sandby is actually a transitional one which evolved quite independently of colonial experience.

At any rate, whatever its inspiration, this style was in turn replaced very soon afterwards by the magnificent goatskin knapsack, a popular if not universal choice with many regiments up until the introduction of the standardised Trotter knapsack at the beginning of the 1800s.

The earliest reference to goatskin knapsacks may be in Bennet Cuthbertson's 'A System for the Compleat Interior Management and Economy of a Battalion of Infantry' - Dublin 1768:

"Square knapsacks are most convenient, for packing up the soldier's necessaries, and should be made with a division to hold the shoes, black-ball and brushes, separate from the linen; a certain size must be determined on for the whole, and it will be a pleasing effect upon a march, if care has been taken, to get them of all white goatskins, with leather slings well whitened to hang over each shoulder; which method makes the carriage of the knapsack much easier, than across the breast, and by no means so heating."

Since he elsewhere recommends the use of smooth white buff for the accoutrements it may confidently be supposed that the reference here to "leather slings well whitened" means that Cuthbertson intended that they should be made of ordinary tanned leather -, probably because it was much less prone to stretching than buff. This is an important consideration when any strain is to be placed on leather, although buff does in fact appear to have been widely used, and was certainly used for the Trotter knapsack.

The best surviving depiction of a goatskin knapsack which I am aware of appears in Beechey's portrait of Captain John Clayton Cowell, I/Royals, c1795. The gallant Captain, who at that time had just returned from San Domingo, is attended by his faithful dog while his soldier servant lurks in the background with what appears to be the wretched animal's bean bag under his arm. Quite providentially and most unusually we are treated to a rear view of this anonymous individual - and his knapsack.

The rather elongated appearance of the knapsack is accounted for by the fact that his blanket can just be seen rolled under the flap, rather than strapped on to the outside. The eagle-eyed amongst you will doubtless have seen this practiced by the 60th Foot in the recent version of "The Last of the Mohicans".

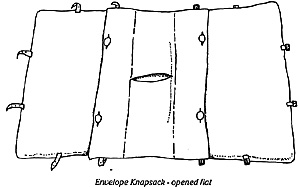

In parallel with the goatskin knapsack another style appeared, made from canvas and waterproofed with paint. Not only was it cheaper than the goatskin version but it seems to have been regarded as neater and more useful - and probably didn't smell so badly when it got wet. Like the goatskin, the Envelope Knapsack was worn square on the back, but there the resemblance ended. Happily a number of examples of this type have survived for one reason or another, and it is therefore possible to describe it in some detail.

Bennet Cuthbertson would certainly have approved of this style for as the sketch shows it comprised no fewer than three quite separate pockets; two large ones which folded against each other and a central one, accessed from a slit, for blackballs and other dirty items - it is just possible to squeeze a pair of shoes inside it.

The blanket, when carried, was folded between the two pockets, within the knapsack itself. Both this style and the goatskin knapsack are much superior to the 19th century Trotter knapsack in this regard. The blanket is strapped to the top of the latter in marching order, which is fine for balance, but severely restricts the soldier's ability to look about him - no problem on parade of course but a distinct disadvantage on actual service and in particular in skirmishing, which is probably why a number of illustrations from the period after 1815 show the blanket folded within the knapsack straps themselves against the rear face of the knapsack.

In the surviving examples the outer part of the Envelope knapsack - not seen in the sketch - was made from stout canvas, waterproofed with paint, while the inner pockets were made from a lighter weave of coarse linen. The dimensions of the knapsack when fastened up were 17" x 19" (which works out slightly larger than its replacement, the Trotter knapsack which is 12" x 17").

The colour of this knapsack varied according to the whim of the Colonel, although yellow ochre seems to have been the commonest one. In the centre of the outside face was a roundel, gener* red in colour, bearing the regiment's number and or designation, and sometimes a badge as well.

Once again there are a number of variations and some units had either the roundel or even the whole of the knapsack painted in the regimental facing colour. The short lived 97th Highlanders for example had the arabic number 97 painted in black on ochre, surrounded by a green ring (the facing colour) bearing the legend Inverness-shire Regt in white capitals. Its sister fencible battalion on the other hand, also with green facings, had green painted knapsacks with the designation IF (for 1st Fencibles) and the company number painted on a black disk. Other variants can be seen in the National Army Museum and in some of Dayes' watercolours.

The choice of goatskin or canvas knapsacks was left to the individual regimental colonels, although the Horseguards gave a decided nudge towards the canvas variety by allowing only 5s 6d for each. Goatskin knapsacks purchased by Cox & Co. for the Gordon Highlanders in 1796 cost 7s.

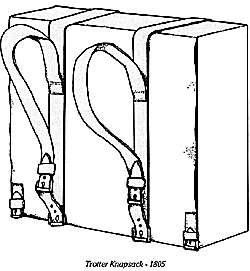

In 1805 a new universal pattern designed by a military contractor named Trotter was accepted for service, although it took some time to phase in and the old style may still have been used by some militia units as late as 1815.

The Trotter has had a pretty bad press, but as it remained in use (albeit with minor modifications) for the next sixty-six years, modern criticism has probably been misdirected. It was in fact quite a revolutionary design with some useful features.

The most obvious departure from previous designs was of course the insertion of a wooden frame which at once gave it some rigidity and allowed a smart appearance on the parade ground. (The Guards are confidently rumoured to have still been stiffening their knapsacks with bits of plywood within living memory - but then they always have been a funny lot).

Just how uncomfortable this wooden frame actually made the knapsack is debatable. Armchair experts might usefully reflect on how much more uncomfortable a modern radio transmitter or a packboard laden with mortar rounds can be.

In point of fact the real problem which afflicted the soldier was not the design of his knapsack but the amount of kit which he was expected to carry in it. On the barrack square of course, if full marching order was called for, the rigid frame allowed our hero to parade with an empty knapsack and according to some memorialists this was not unknown on campaign. More commonly perhaps, contemporary illustrations suggest that once on active service, removal of the boards very quickly came under the heading of a time-honoured practice.

The Trotter knapsack also differed from previous designs in that it was designed rather like a suitcase or valise with a canvas 'lid' at the rear. Once again modern reconstructions depicting the flap or lid as being the outer face are erroneous.

Perhaps the most revolutionary feature of the design, however, was the arrangement of the carrying straps, In both the canvas envelope and goatskin styles both ends of each shoulder strap are firmly anchored - sewn -to the inside face of the knapsack and cannot be adjusted. Once again modern reconstructions featuring a toggle fastening at the bottom end, as in the French service, aare unsupported by contemporary evidence. Instead adjustment is effected by means of a slightly narrower breast-strap.

The Trotter differed from previous practice in that the straps were not an integral part of the knapsack. Indeed it can best be considered as a separate valise enclosed within a carrying harness. As can be seen by the accompanying sketch the valise was encircled by two buff leather straps, fastened with buckles at the bottom. The actual carrying straps, also made from buff leather, were attached not to the valise but to the straps encircling it.

It was thus possible to contrive a light marching order by leaving the valise in store and rolling the blanket and other essential items in the knapsack straps.

For the sake of clarity the breast strap and blanket straps have been omitted from the sketch. The latter were attached to the top of the knapsack straps. Latterly flattened brass rings were employed for the purpose, but it is unclear whether this was also the case with early versions.

The Trotter's comparatively advanced carrying harness also permitted the attachment of additional items such as messting, and firewood - which brings us back to the undoubted fact that a soldier's chief purpose is to hang things on.

Note on sources

This article has, with the exception of the quote from Bennet Cuthbertson, been prepared solely by reference to the illustrations referred to, and to surviving examples of knapsacks. Some use has also been made of reconstructions in assessing the relative merits of the different styles.

Back to Napoleonic Notes and Queries #11 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1992 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com