Military Reform

The Ottoman military began to fall behind western armies during the late seventeenth century. Europe began to develop better muskets and the Ottomans failed to keep up with the technology. Lighter guns were developed, as well as changes in the compound ratios of salt-peter, charcoal, and sulpher used to make gunpowder. This new ratio made gun powder more stabile. Even improved alloy of the metal for making these weapons increased the desparity. As late as 1793 the Ottomans had only bronze cannons.

The Ottoman ruling class prevented this new technology. They looked at new technology as something that was developed by infidels. The decay that had infected the military also attacked the niilitary industry. Weapons were of poor quality, metal was badly forged and extremely brittle. As previously stated, the gunpowder was of poor quality because it had impurities and was highly erratic. Muskets and artillery pieces had a very high rate of failure.

Most of the Ottoman gunpowder was manufactured at the Imperial Powder Works (Baruthane-i Amire) at Bakirkoy, just north of Istanbul. There were smaller areas of production throughout the Empire at Baghdad, Belgrade, Galipoli, Izmir and Salonika. The managers of these factories purchased their position and they increased their profits by lowering the quality of the gunpowder. The Ottomans were still using the sixteenth-century formula for gunpowder: 6-1-1, saltpeter, charcoal and sulphur ratio. This compares with the eightenth century formula of 75-15-10, which results in a more stable and dependable compound. Animal power was used in the factories, which caused problems since the wheel moving in the mill could not move at a constant rate. The European powder works relied on water to generate the proper wheel motion. The Ottoman ratio had as good a chance of igniting from a change in the climate as it did from actually lighting it.

With the manufacturers adding other impurites to save money, it only added to its instability. The charges were either too small to have the proper effect or were too large and could cause the weapon to explode in use.

Mahmut I, or Mahmud I, became the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire in 1730. Mahmut knew that he needed military reform for the empire to survive. A European advisor, Claude-Alexander Comte de Bonneval, was hired by the Grand Vizier Topal Osman Pasha to oversee the reforms. Bonneval was only accepted after he converted to Islam and took the name Ahmet.

The Grand Vizier assigned Ahmet to revive a former unit, the Bombardier (Humbaraci) Corps. Bonneval was very active. His Bombardier Corps was based on current French and Austrian organization. He also tried to modernize the military arms industry. Unfortunately, Bonneval's career and the Bombardier Corps rested with the current Grand Vizier.

Mahmut went through several Grand Viziers; and eventually one was appointed who disliked Bonneval. The Janissaries also felt threatened by the Bombardier Corps, so it was disbanded by Mahmut. The threat of a Janissary revolt could always sway current policy and so they were always a strong political force within the empire.

One final note, the bayonet was not introduced until the late 1790's. Prior to this, swords and spears were used for melee weapons. Against the Austrians and Russians, the usual tactic was to use the musket at a distance and then drop the weapon and close in for melee. Of course, these units would have no musket for defense after the initial melee.

Flags, Tughs and Standards

Flags were a visual symbol of the Empire. They were also considered an expression of the political and religious ideas. Often, the Ottomans used a special flag called a gonfalon--this was a flag that hung from a cross bar. They also used the banderole or streamer.

Flags were a visual symbol of the Empire. They were also considered an expression of the political and religious ideas. Often, the Ottomans used a special flag called a gonfalon--this was a flag that hung from a cross bar. They also used the banderole or streamer.

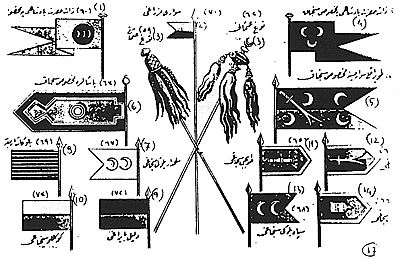

An assortment of Ottoman standards is depicted in the above postcard, from the collection of Brian Vizek. Note the horsehair tughs in the center and the Zulfikar sword on flag numbers 5 and 12. Nos 11 to 14 are Janissary Orta standards.

The majority of Ottoman flags were rectangular or triangular in shape. The rectangular flag was the most dominate style, and both of them had borders. The Ottomans would often increase the number of flags before a battle. A red flag noted the right side of a unit and a yellow flag the left. The cavalry primarily used red and yellow flags.

The Janissary companies had individual flags which had symbols such as a tent, mosque, bow, elephant and Arabic symbols. The Sultan was accompanied by seven flags and the Grand Vizier by five. Furled flags were in green linen. The flag poles were usually red.

There were three common flag styles used between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries: two basic and one intermediate type. The difference between them was in the content of the main field of the flag. The first basic is an inspirational type. It is covered with writings in Arabic and could be monumental in size. The second basic, the Zulfikar type, is dominated by a sword (Zulfikar style which resembles a pair of scissors-two blades) with an inscription and other graphic elements in the main field. The intermediate type of flag is similar to the Zulfikar, but without the sword. There is usually one or two fields, with the fields divided by a set of elements such as stars, crescents, suns, etc.

The middle 1700's were known as the Tulip Period, since tulips were a very popular symbol within the empire. This carried over to their flags as well. The Zulfikar flag would frequently have numerous stars, moons, crescents, etc. formed in the shape of a tulip. The Sultan's flag was usually white, but sometimes red, green, and yellow would be used.

The Tugh was the most popular form of cavalry standard. The tugh was basically several horse tails attached to a wood pole. The tip of the pole was often decorated with an ornamental onion-shaped ball (finial). More elaborate finials might include a star or crescent, etc.

At the beginning of a campaign, two tughs were set up in the Palace courtyard if the Sultan were to lead the army, while one tugh indicated the leadership of the Grand Vizier. In battle, the tugh was not carried at the head of the unit, but usually marked a rallying point for the unit or denoted the position of the leader of the unit. The number of tughs designated the rank. The Sultan carried as many as seven to nine and the Grand Vizier would have five. The number could also vary by region. The eastern Turks carried nine tughs, western Turks carried seven, and the Sadrazarn carried three.

Tactics and Organization

Prior to the eighteenth century, all of the Ottoman military campaigns were fought in foreign lands. The general plan was to take the offensive and march towards one definite target. There, one quick and decisive battle would be fought and won and then the campaign would be over. The subjugation of Hungary following the decisive Battle of Mohacs in 1526 is a classic example of an Ottoman campaign. Defense was not a high priority since the Ottomans felt that they could successfully take the war to their opponent and fight on his land.

The Divan-i (war parliament) would make recommendations for war and also develop the campaign plan; however, the Sultan would have the final say on this decision. Once war was declared, word was sent to the individual Ottoman states or vassals detailing their contribution to the war effort. In addition to troop and supply requirements, they received information on where the troops were supposed to assemble. There were usually two methods of assembling the invasion army. One was for all troops to assemble at a common starting point, such as Istanbul, or the troops might join the army as it marched through their homelands on the way to the chosen target of attack. The campaign season lasted from May to November. Once the winter arrived, the feudal levies wanted to return to their homelands and harvest their crops.

The Ottoman Empire was on the defensive during the wars of the eighteenth century. The glory of the Janissaries and Spahis had long passed. All of the military contingents that fueled the expansion of the empire now had outside interests. They found that a great amount of wealth was to be found in commerce and trade, especially given their tax-exempt status. In the 1700's the wars were fought when Ottoman land was invaded or when religious conflict arose. The wars with Austria, Russia and Persia were all defensive in nature.

In Europe, the Ottomans faced armies that were modernized and capable of campaigning during the winter, whereas the Ottoman army was not markedly different from the one that besieged Vienna in 1683 and its troops tended to evaporate in the winter.

The fact that the Ottomans only lost the Crimean peninsula and minor holdings in the Balkans was attributable more to outside influence (balance of power concerns) rather than Ottoman military prowess. The desires of the rest of Europe, particularly England, France and Prussia, to keep a balance of power in eastern Europe pressured the Austrians and Russians to come to terms and to limit their expansion in this part of the world.

Ottoman Military Units: Overview

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal Vol. VII No. 2 Table of Contents

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1994 by James E. Purky

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com