The General Situation

The General Situation

The Count von Maxel, commanding the forces of the Elector of Bavaria, was advancing to the Guisfeld (an open field southwest of the village of Kleine Guisdorf) with the objective of offering battle to the Saxons. To affect his deployment he had to cross the River Guis.

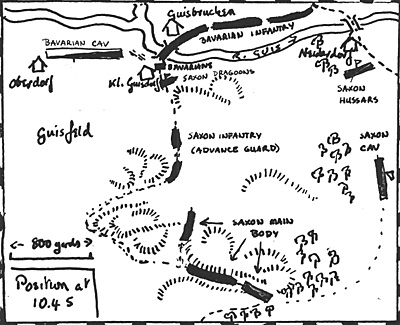

MAP 1 : The early crisis depicting the moment when the Saxon dragoons charged the Bavarian artillery train as it crossed the Guisbruck. Note the position of the Bavarian cavalry.

The Saxons, commanded by the Duke of Saxe-Lamiter, were obliged to debouch from a narrow defile through the foothills of the Giant Mountains and the forests which covered them.

Both armies were about 14,000 men strong. The Saxons had a decided superiority with respect to cavalry and a numerical superiority in artillery pieces; however, a significant proportion of their troops were of indifferent quality. The Bavarian host was exceedingly well-disciplined and included some grenadiers of elite status. Although they had fewer cannon, the Bavarians possessed a brigade of heavy artillery. The Bavarian forces would be advancing from north to south and the Saxons would be advancing from the south.

| FORCES AVAILABLE | ||

|---|---|---|

| CAVALRY | BAVARIAN | SAXON |

| Cuirassier | 12 sqds | 15 sqds |

| Dragoons | 15 sqds | 21 sqds |

| Hussars | 3 sqds | 12 sqds |

| INFANTRY | BAVARIAN | SAXON |

| Grenadiers | 2 btns | - |

| Line | 15 btns | 10 btns |

| Territorial | - | 4 btns* |

| ARTILLERY | BAVARIAN | SAXON |

| Heavy | 1 brigade | - |

| Light | 1 brigade | 3 brigades |

| * poor quality troops | ||

Total Forces Available:

Bavarians: 30 squadrons, 17 battalions and 40 guns total troops 13,900 with 5 generals

Saxons: 51 squadrons, 14 battalions and 60 guns total troops 15,000 men with 5 generals

The approach of both armies to the field of conflict was along a single road. The order of arrival of the troops was therefore predetermined. Von Maxel adopted a simple organization: cavalry followed by artillery followed by infantry. Saxe-Lamiter, by contrast, followed a more complicated deployment:

Advance Guard-9 squadrons dragoons, 7 battalions infantry and 1 battery of artillery.

Main Body-15 squadrons cuirassiers, 3 battalions line infantry, 4 battalions territorial infantry and 2 batteries of artillery.

Rear Guard-9 squadrons dragoons.

Initial Intentions

The River Guis is fordable only with difficulty. There are two bridges: one at Guisdorf in the center of the field, and another one at Neiderdorf on the left of the Bavarian advance. Despite the latter bridge being closest to the Bavarian point of debouchment, Von Maxel decided to ignore this wing completely. The whole of his army marched to the central bridge with a view to deploying in the open ground of the Guisfeld to the west of this bridge. The Bavarian cavalry was to occupy the Guisfeld to the right of Kleiner Guisdorf, but because they anticipated superior enemy cavalry, they were to adopt a defensive attitude until the strong infantry force came up to deploy in front of them. Once this had been achieved the whole army was to begin a triumphal advance across the Guisfeld.

The Bavarian plan left their line of communication leading away from their left wing. It was a bad strategy, especially if the Saxons also happened to deploy on the open Guisfeld.

Saxe-Lamiter perceived the situation differently. His Advance Guard cavalry was sent, pell-mell, along the high road to Kleiner Guisdorf with a view to seizing as much ground as possible and disrupting the deployment of the Bavarians. The hussars were sent towards Neiderdorf, similarly, to disrupt any enemy deployment there. The infantry of the Advance Guard followed their cavalry with a view to supporting it and covering the deployment of the main body in the foothills of the Giant Mountains. While the heavy cavalry followed in the footsteps of the hussars, the infantry of the main body, followed by the rearguard, defiled through the foothills to deploy on the high ground in the center. Thus it was that the two commanders had totally different plans to bring about a regular engagement. What followed, however, was not without interest.

The Early Crisis

The Saxons arrived on the Guisfeld first; the dragoons of the Advance Guard trotted smartly down the winding road and the infantry marched in sprightly fashion behind them. They had only the briefest advantage in time, for fifteen minutes later, the head of the Bavarian column appeared. (9:45 A.M.)

An observer seeing these two events might have assumed that these two columns were destined to meet somewhere south of Klein Guisdorf. However, an overnight rain had dampened the roads so that there were no dust clouds to reveal the advance and for a long time neither side appeared to be aware of the presence of the other. The rendezvous was not kept.

Instead of continuing along the high road, the Bavarian column turned west behind the village of Kleine Guisdorf. This was to carry out its instructions to occupy the Guisfeld.

The Saxons were not so hesitant. Did ever a more glorious sight great the commander of an advance guard as he approached Klein Guisdorf? The Bavarian cavalry column had already filed away behind the unoccuppied village. There, in the process of following it, but on account of their slower rate of march, some half mile behind, came the head of the artillery column in the act of crossing the Guisbrucken bridge. Without hesitating to deploy the Saxon commander hurled his three leading squadrons at that hapless band of Bavarians while the remainder of his cavalry deployed orderly in support.(10:30 A.M.)

The Bavarians were marching in a single column. Their cavalry were too far ahead to protect their river-crossing. Behind the river the splendid battalions were likewise impotent. What could a handfull of gunners effect against such an onslaught?

But these gunners were heroes. Disorganized as they were, the Saxon dragoons could only fight as individuals and the artillerymen took full advantage of the cramped bridgehead. Even heroes should have been ridden down in such circumstances, but perhaps the dragoons, sensing that they were but 300 men attacking 14,000, had little stomach for the fight. Thus it was that this arrow, which had seemed to pierce the heart of the Bavarian column, was blunted.

Now the valiant Bavarian gunners strove to clear the bridge and link up with their cavalry. Behind them the grenadiers, the finest troops on the field, filed across the bridge and, rather late, provided the flank guard which might protect the deployment of the army.

Colonel Von Hessedam, the Saxon cavalry commander, gathered his six remaining squadrons of dragoons, which he had deployed under cover of the first attack,and ordered the trumpets to sound the charge. Where a handful of gunners had repulsed one attack, what might .now be expected of elite grenadiers? The Bavarians had recovered from the shock of the initial cavalry attack and they awaited the second Saxon cavalry attack with confidence.

Through the foothills the Saxon columns toiled as, hearing the signal of battle they sought to succour their Advanced Guard, who may yet have, in eagerness, have overstepped the mask of prudence. Unopposed, the Saxon cuirassiers and hussars made their way to Neiderdorf, while away to the west, the Bavarian cavalry deployed in the open Guisfeld and awaited orders. The crisis was at hand.

Boldly the Saxon dragoons built up their momentum. Hastily deployed, the Bavarian grenadiers nervously fingered their muskets. Without orders, a hesitant fire began. Somewhere the cry went up that the grenadiers were about to be outflanked! Many of those men who so recently had crossed the bridge now decided that it would be safer on the other side. Incredibly, the grenadiers threw down their muskets and fled. The Saxon dragoons rode up to the bridge triumphant and unopposed.

The rout of the grenadiers threw the entire Bavarian line into disorder. The first brigade infantry were demoralized by the defeat of the crack troops. They panicked and fled back up the road from where they came. The Bavarian artillery, thinking that the danger had passed, now found their rear threatened. They abandoned their guns and ran to their cavalry for protection from the Saxons.

On the Saxon side, elation over success did not give way to undisciplined action. Even considering the degree of disorder that was evident across the bridge, it would have been foolhardy for 600 men to charge 10,000. While the Bavarians struggled to regain their order, the Saxon columns toiled across the hills. The battle was not yet over.

Developments

There was still the possibility of a bold counter stroke by the Bavarian cavalry against the struggling Saxon infantry columns, but the Bavarian horsemen had no orders and the Count von Maxel could not have known of the opportunity that was present. It was some time before the Saxons could get orders to their troops to take advantage of the position.

The Saxon Advance Guard infantry moved forward to occuppy Kleine Guisdorf and support their cavalry. Half went on to confront the Bavarians on the other side of the river while the remaining battalions faced west behind Kleine Guisdorf. The main body of Saxons followed up behind. The second phase of the battle began (11:00 A.M.).

While the Saxon hussars and advance. guard held the Bavarian infantry in awe, the main body supported by the heavy cavalry swung due west to confront the Bavarian horse in the Guisfeld.

Once order had been restored, there was little that the Bavarian infantry could do than line the river bank and fire idly at the Saxons on the far bank. Had they attempted to cross, it was almost certain that the Saxon horse would have charged them as they struggled out of the stream. A few battalions attempted to cross the river further upstream to succour the Bavarian horse, who now decided to take matters into their own hands.

As the Saxon line advanced, the Bavarian horse charged it obliquely. A withering fire greeted this attempt. Twice did the Bavarian horse attempt to break the first Saxon infantry line, but nothing could stop its steady advance. Had they succeeded, there was a second line behind, and manning the third line were the Saxon cuirassiers. The Saxon dragoons of the rear guard had taken post on the left wing of their infantry, whose opposite fink was firmly anchored on Kleine Guisdorf.

Outnumbered and outflanked, there was no way that the Bavarian horse could bring on combat with any advantage. Half of the Bavarian squadrons were shattered from the two previous attacks on the Saxons, and the remainder were forced to yield ground as the Saxon infantry line advanced in their direction. Discretion proved to be wiser course and so the Bavarian cavalry retired across the Guisbruck before the Saxon cavalry could be brought forward to adminster the final coup de grace. (1:00 P.M.).

Despite the decisiveness of the battle, casualties were slight on both sides. On the Bavarian side, Prince Klemens, Duke Charles and 1700 rank and file were hors de combat. The 20 guns of the heavy artillery were abandoned. The Saxons lost approximately 300 men.

Comments On The Game

The terrain and armies were chosen by player "N" and the choice of side and army by player "L". During the early stages of the battle, the dice seemed to favor the Bavarians, who really would not have been expected to repel the first onslaught. This good fortune was soon offset by the failure of the grenadiers. Later, the Bavarian cavalry suffered from poor die rolling, but the situation in which they found themselves in towards the latter half of the battle would have required extraordinary fortitude to triumph.

With respect to strategy cards, the Saxons drew first. This gave them a good edge and allowed them to gain the favorable ground first. During the later stages of the battle, the Bavarians drew strategy cards immediately after the Saxons. This might have allowed them to respond more effectively in an open conflict, but in this action, the opportunity for such initiative passed once the Bavarian line of battle was broken.

Four hours of "real time" were played in about two hours. The ground scale used was one inch equal to one hundred yards and the figure scale was one casting equal to one hundred men. Strategy was determined by drawing a card before each move. Four of the sixteen strategy cards allowed the player to change orders, otherwise, brigades were required to maintain orders given to them previously. The tactical rules were designed by Neil Cogswell.

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal Vol. VII No. 1 Table of Contents

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1993 by James Mitchell

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com