The year 1740 appears to be one of those milestone moments in history when a series of unrelated events all lined up in a sort of political "harmonic convergence" and abruptly changed the status quo. The events of 1740 would elevate Prussia to the first tier of European powers, which in and of itself, would have a profound impact on Central European politics for many generations to come.

The year 1740 appears to be one of those milestone moments in history when a series of unrelated events all lined up in a sort of political "harmonic convergence" and abruptly changed the status quo. The events of 1740 would elevate Prussia to the first tier of European powers, which in and of itself, would have a profound impact on Central European politics for many generations to come.

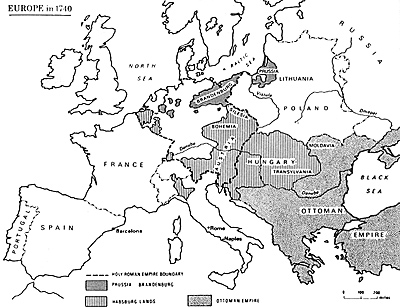

Things were out of kilter to begin with; the traditional land powers, France and Austria were still weakened by the decades of war that ended with the Peace of Utrecht in 1713. Spain and Holland were traditional maritime powers that were now in decline and Sweden had been eclipsed by Russia as the power in the north and eastern part of the Baltic region. In contrast, England was rich and powerful with a strong maritime trade and colonies scattered across the globe.

The European periphery included Italy, which was a fractured mosaic of petty kingdoms, city-states, duchies, and republics; the Balkans, which were contested by Austria, Russia, and Turkey; and Poland, once a great kingdom, but now torn apart by a feuding noblility. Then there was the odd collection of German states known as the Holy Roman Empire, which was made famous by Voltaire's remark that it was neither holy, nor Roman, nor an empire.

The Empire was nominally ruled by an emperor, traditionally a Hapsburg, and selected by seven kurfursten or electoral princes. Three were spiritual rulers - the Archbishops of Mainz, Cologne and Trier; and four were secular -- the Duke of Saxony, the Count Palatine of the Rhine, the Margrave of Brandenburg and the King of Bohemia. The electors and most other princes of the Empire were autonomous entities, though they swore fealty to the emperor.

Thus the ruler of all the Hapburg domains could simultaneously be a duke in Austria, Moravia and Silesia; a king in Bohemia and Hungary; and Holy Roman Emperor. The later title carried more tradition than power. By the 18th Century, the Empire had evolved into a loose confederation of independent states. The most powerful of these were Hanover, Brandenburg-Prussia, Saxony, Bavaria, Wurttemburg and the collection of Hapsburg lands.

The death of three important monarchs in 1740, combined with the weakness of France and Spain and the English indifference to continental affairs, created a power vacuum in Central Europe and opened the way for Prussia to step onto the main stage.

These events occurred:

May 28, 1740

Frederick William I of Prussia died and was succeeded by his son Frederick II. His father left him a legacy of solid finances, a treasury surplus of 10 million thalers and a standing army of 83,000 of the finest troops in Europe.

October 20, 1740

Charles VI, Holy Roman Emperor and ruler of Austria, gobbled down a plate of fresh mushrooms and died that evening from indigestion. He was succeeded by his 23 year old daughter, Maria Theresa, and he left her a legacy of poor finances, a weak army of 108,000 men and a scrap of paper called the Pragmatic Sanction, which ostensibly guaranteed her right to rule the Hapsburg domain. The astute Prince Eugene of Savoy though noted that an efficient army and a full treasury were the only effective guarantees in the world.

November 9, 1740

The Empress Anne of Russia died and was succeeded by her two month old nephew Ivan IV. An assortment of plots and counterplots by successive regents culminated in a palace coup in 1741 in favor of Elizabeth, daughter of Peter the Great. Russian turmoil guaranteed the safety of Prussia's eastern flank should Frederick go to war with Austria.

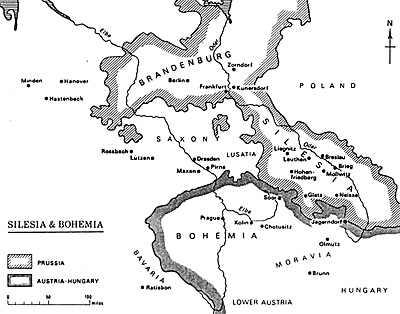

It seems that only Frederick II had the means and the willingness to fill the power vacuum in Central Europe. Upon hearing the news of the Emperor's death, Frederick resolved to take the rich province of Silesia from the Hapsburgs. Silesia would add another 1.5 million people to the state, along with 14,000 square miles of land contiguous to Brandenburg-Prussia as well as a thriving textile manufacturing industry. Frederick was astute enough to realize that no other European power could stop him, and besides, he correctly counted on the greediness of other states to join him in a feeding frenzy on Hapsburg territory.

Charles Albert, the Elector of Bavaria, presented himself as a male heir through his distant descent from a daughter of Ferdinand I (Austrian Hapsburgs) circa 1556. Phillip V of Spain made an equally spurious claim going back to an alleged treaty between Charles V of Spain (Spanish Hapsburgs) and his brother Ferdinand I of Austria in the mid 1500's. Augustus III of Saxony entered a claim based on his marriage to the eldest daughter of Joseph I, the brother of Charles VI.

Frederick now presented his claim to a portion of Silesia and offered to take the field on Austria's behalf to settle the Austrian succession question within the Empire if only Austria would cede Lower Silesia to Prussia. Even as he awaited the inevitable Austrian rejection of his proposal, Frederick was preparing for war, and on December 13, 1740 he dispatched an army of 20,000 infantry and 8,000 cavalry towards Silesia. On December 16, the Prussians advanced across the frontier and into Silesia. An additional force of 12,000 men departed Berlin two days later under the command of the hereditary Prince of Anhalt-Dessau (the "Young Dessauer").

Frederick now presented his claim to a portion of Silesia and offered to take the field on Austria's behalf to settle the Austrian succession question within the Empire if only Austria would cede Lower Silesia to Prussia. Even as he awaited the inevitable Austrian rejection of his proposal, Frederick was preparing for war, and on December 13, 1740 he dispatched an army of 20,000 infantry and 8,000 cavalry towards Silesia. On December 16, the Prussians advanced across the frontier and into Silesia. An additional force of 12,000 men departed Berlin two days later under the command of the hereditary Prince of Anhalt-Dessau (the "Young Dessauer").

The Austrian forces in Silesia amounted to no more than 3,000 foot and 600 horse, and most of these, save for the garrisons at Glogau, Neisse, and Brieg, were driven out of the province by the end of January 1741.

The success of Frederick's conquest would ultimately depend on two things: first, the ability to hold it against an Austrian counter-attack and secondly, the reaction of the other European powers, France in particular. If both France and England were prepared to honor their respective committments to the Pragmatic Sanction, then Frederick would have to give up Silesia. However, the war party in France, led by Marshal Belle-Isle, won the ear of king Louis XV and within six months of the Prussian invasion of Silesia, a French army was crossing the Rhine and marching towards Vienna, ostensibly as paid auxiliaries of the Bavarian elector. There was no declaration of war.

Frederick would ultimately defeat an Austrian army of 18,000 men at Mollwitz on April 10, 1740 and by the end of May, an alliance of France, Prussia, Bavaria, Spain and Saxony would be lined up against Austria. A partition of the Hapsburg lands seemed a foregone conclusion during the early months of 1741.

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal Vol. VI No. 1 Table of Contents

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1992 by James J. Mitchell

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com