In preparation for the recent tour of the Czech lands, I had wondered what on earth a visit to the battlefield at Austerlitz could have to do with the Seven years War. I confess that Napoleonic warfare has never held much charm for me being outside the compass of the Age of Reason, but a battlefield is a battlefield and it was still "horse and musket". Reading up the battle beforehand in the excellent account by Duffy, I began to feel a nagging sensation that I had been there before.

In preparation for the recent tour of the Czech lands, I had wondered what on earth a visit to the battlefield at Austerlitz could have to do with the Seven years War. I confess that Napoleonic warfare has never held much charm for me being outside the compass of the Age of Reason, but a battlefield is a battlefield and it was still "horse and musket". Reading up the battle beforehand in the excellent account by Duffy, I began to feel a nagging sensation that I had been there before.

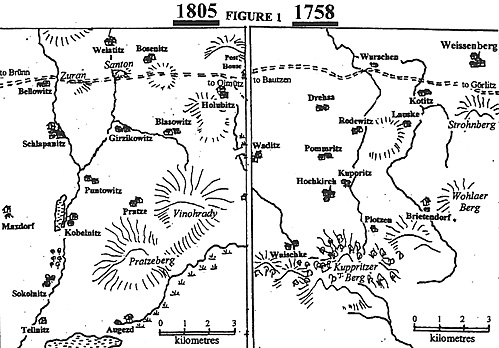

Figure 1 shows, at the same ground scale, the terrain of the 1758 action in comparison with that of 1805. As my points of reference, I choose the villages of Hochkirch (1758) and Kobelnitz (1805).

What particularly bothered me was the extraordinarily bold battle plan of the Allies. What was it that had convinced General Weyrother that his outflanking movement could succeed? What was it about the plan that allowed him to convince the other generals and the Emperor Alexander? And then there is the greatest enigma of all: how did it come about that Napoleon managed so accurately to predict the Allied operations?

In the days before the battle, Napoleon had deliberately given up to the Allies a strong position extending from North of Holubitz to the Pratzen Heights. The natural inclination of the hugely experienced Kutuzov and most other Austrian or Russian generals would have been to sit on those heights and simply wait for the French to retreat. Had they done so, Napoleon would have had little option than to hurl his Grand Army in a frontal assault against an army in position on the heights that he had so rashly vacated or to retire in an undignified manner along his over-extended line of communication. Yet Napoleon deliberately chose the field of battle with a view to enticing the Allies to manoeuvre exactly as they did. Why was the bait so enticing?

As a staff officer and planner, General Weyrother will undoubtedly have had an encyclopaedic knowledge of military history. In particular, he will have studied the battles of the preceding century. One would imagine that at any Austrian Staff College the battles of Eugene, Daun and Loudon must have been exhaustively explored and probably refought on sandtables. Perhaps, as a young officer, he had even been instucted by Lacy himself. Had General Weyrother become obsessed by one battle in particular - perhaps to the extent of writing a learned treatise on it - and was Napoleon, who was no slouch when it came to studying the lessons of history, aware of that obsession?

I believe that Weyrother based his plan on that greatest of Austrian offensive victories of the Seven Years War - Hochkirch 1758. Let us imagine for a moment how he might have argued.

The Terrain

The most significant feature of each field is the height 3 kilometres SE of that reference point - Kuppritzer Berg (1758) and Pratzeberg (1805). The rugged Kuppritzer Berg is wooded and stands 205 metres above the reference point. The Pratzeberg is more open and stands 115 metres above the reference point. In respect of ease of movement, it is clear that the Pratzeberg offers far less obstruction than the Kuppritzer Berg did in 1758. Indeed, in 1758 it had been necessary to prepare roads through the woods to enable the troops to reach their forming up positions. Such preparation is not required in 1805 and therefore we may anticipate that the probability of achieving surprise will be greater in 1805 than in 1758 and that, in the manoeuvre that is proposed, the columns will arrive at their destination with less disorder.

The heights extend North-Eastwards from their peak - across the Wohlaer Berg to the Strohnberg (1758) and over Vinohrady to the heights around Holubitz (1805).

In each field, the ground is intersected by a number of streams running in a North/South direction. In 1758 those streams ran in a generally North direction whereas in 1805 the direction of those waterways is generally South. These streams are not of themselves major obstacles; there representation here indicates the more gentle slopes of the hills and valleys.

Across the North of the field there runs a major highway - Bautzen to Gorlitz (1758) and Brunn to Olmtitz (1805). In 1758 the Prussian communications lay through Bautzen to Dresden; in 1805 the French communications are through Brunn to Vienna.

Relative Forces

In 1758, the Prussians disposed 30,000 men in their camp at Hochkirch; Marshal Daun had 78,000 on the heights. In 1805 we may estimate that the French have about 60,000 men in position between Kobelnitz and Bosenitz whilst the Allies can deploy 100,000 men. The total forces on each side in 1805 are significantly greater than in 1758. Whilst in 1758 Marshal Daun enjoyed an advantage of about 2.5:1; the Allied advantage in 1805 is just less than 2:1.

However, it must be remembered that the army of Marshal Daun had not been engaged in battle since the disasters that closed the year 1757 and that army included a high proportion of untried troops as well as numerous Croats. The Allied army of 1805, by contrast, has the inestimable reinforcement of two Emperors. Thus, although the disparity in numbers is not as great as in 1758, we may confidently presume that the numerical odds favour the Allies in just the same way in 1805 as they did the Austrians in 1758.

It may be argued that additional French forces could reach the field. It is at least probable that the French have taken their present position in order to facilitate the arrival of a further 13,000 men with Bernadotte from Bohemia before they withdraw together to Vienna. Indeed it is possible that advance elements of that Corps have already reached the field. The expectation of the arrival of Bernadotte only emphasises the need to strike rapidly. The possibility of the Corps of Davout - last heard of two days ago in Vienna - reaching the field can be entirely discounted. It would have been as likely that Prince Henry from Dresden would have intervened at Hochkirch in 1758!

Initial Dispositions

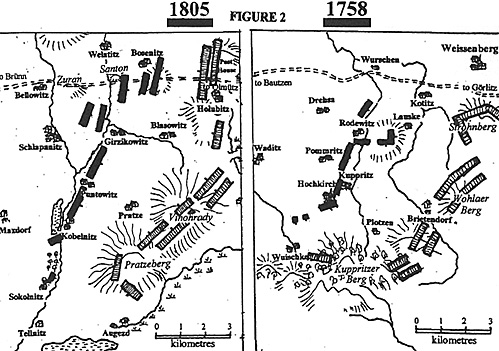

Figure 2 indicates the initial disposition of the forces.

Figure 2 indicates the initial disposition of the forces.

In 1758, the Prussians had sought to occupy the Stronberg in order to cover their march to Gorlitz but had been forestalled by the Austians. As a result, the Prussians were obliged to make their camp in the low ground between Hochkirch and Rodewitz with General Retzow occupying and advanced post in front of the latter village. In 1805 the French have been driven back along the road from Olmutz. Presumably because they had insufficient numbers adequately to occupy the heights between Holubitz and the Pratzeberg - a position facing East of immense natural strength - the French have been obliged to withdraw back to the valley between Kobelnitz and Welatitz with the Corps of Marshal Lannes holding an advanced post (analogous to that of General Retzow in 1758) near Bosenitz.

As in 1758 the Austrians occupied the high ground from the Kuppritzer Berg to the Stronberg, so, in 1805, the Allies hold the heights from the Pratzeberg to Holubitz overlooking the position of the enemy.

The greater numbers of troops deployed in 1805 means that the position occupied is more extensive than in 1758. However, that extension is to the North of the reference point of Kobelnitz - away from the place where the decisive action will occur.

The Plan of Attack

As in 1758, the attack in 1805 will be a left flanking march by a number of independent columns. Whilst the armies of 1758 tended to operate by Wings or Lines of cavalry or infantry, in 1805 we shall employ the modem all-arms divisional structure for the columns.

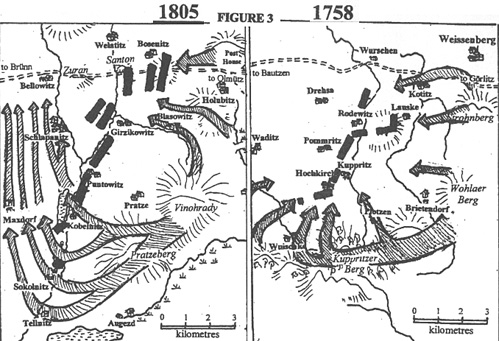

Figure 3 shows the operation of Marshal Daun in 1758 in comparison to the plan of 1805.

Figure 3 shows the operation of Marshal Daun in 1758 in comparison to the plan of 1805.

Consider first the Northern sector of the field. In 1758 Buccow and Arenberg attacked the forward post of Retzow. In an analogous move in 1805, Bagration supported by the Guard and the cavalry of Liechtenstein is to attack Lannes. As in 1758, the attack of Bagration is not intended as full-bloodied assault; instead it is designed to pin the Left Wing of the enemy and to prevent that wing sending reinforcements to their compatriots.

The decisive action is to be on the Southern flank. Here, in 1758, a number of concentric columns descended upon Hochkirch. The focus of our attack in 1805 will be the village of Kobelnitz with other columns crossing through Sokolnitz and Tellnitz before turning North the roll up the French line. Only weak opposition is to be expected at this stage of the battle.

One problem in 1758 was that the attack was made during the hours of darkness - at 5 o'clock in the morning. It was not possible accurately to assess the effects of the first onslaught on Hochkirch so that the success of that initial attack was not fully exploited. That delay, combined with the stubborn defence of the churchyard at Hochkirch, enabled the Prussians partially to rally near Pornmritz before retiring off the field. We shall not repeat that error in 1805. The first attacks will start at about 7 o'clock enabling the columns to have the cover of darkness and any early morning mist to approach their objectives but then having full daylight to exploit their initial success.

After breaking through on this Southern front, the attack columns will pivot Northwards on the reference point of Kobelnitz as Marshal Daun had intended to on the reference point of Hochkirch in 1758.

One other disposition remains to be accounted. In 1758, a small column under Colloredo from the Wohlaer Berg had been designated as a link between the Austrian Main Army in the South and the subsidiary attack of Arenberg and Buccow in the North. That force played no significant part in the action of 1758 and so it has been dispensed with in the plan of 1805 and the troops that would have been assigned to it are more fruitfully employed.

Conclusion

The plan of 1805 utilises and improves upon principles thoroughly tested and proved half a century ago against the finest troops in the world. An Allied victory in 1805 is assured.

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal Vol. XIII No. 2 Table of Contents

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by James J. Mitchell

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com