[Editor's Note: By the spring of 1762, a war-weary France was looking for a way out of its seemingly unending and increasingly expensive war with Great Britain. In the New World, French Canada had already fallen to the British by 1760. In India, French fortunes had likewise taken a nosedive. As the French began negotiations for a peace, they seized on a last desperate measure that they hoped might bring a bargaining chip to the negotiating table. This was the seizure of the lucrative fisheries at St. John's, Nova Scotia. Nigel White has provided us with a brief narrative of this little-known but interesting military operation.]

[Editor's Note: By the spring of 1762, a war-weary France was looking for a way out of its seemingly unending and increasingly expensive war with Great Britain. In the New World, French Canada had already fallen to the British by 1760. In India, French fortunes had likewise taken a nosedive. As the French began negotiations for a peace, they seized on a last desperate measure that they hoped might bring a bargaining chip to the negotiating table. This was the seizure of the lucrative fisheries at St. John's, Nova Scotia. Nigel White has provided us with a brief narrative of this little-known but interesting military operation.]

With the British declaration of war against Spain, many of the regiments, which had been serving in North America, were now sent to the new focus point of the war, the West Indies. This however, left many of the garrisons left behind open to any force that could be assembled against them.

The French minister, the Duc de Choiseul, determined on an expedition to capture the weakly held but valuable fishing station of St. Johns in Newfoundland.

1

The Chevalier de Ternay d'Arsac would command the French naval force, with Joseph-Louis Comte d'Haussonville, the troops. 2

On the 8th of May 1762, De Ternay's small force weighed and made sail from Brest, and during a spell of bad weather ran through [British Admiral] Hawke's blockading cruisers. They were seen on the 11th by Captain Joshua Rowley, in HMS Serpent (74), escorting a convoy, who tried to bring on an action, only to see the French outsail him.

On the 20th of June de Ternay came in sight of Newfoundland. The French squadron was spotted on the 21st, and Captain Douglas in HMS Syren (24) at once set off to inform Lord Colville commanding at Halifax on the 24th of June, arriving there on the 2nd of July.

De Ternay's force came to an anchor in the Bay of Bulls on the 24th of June, and d'Haussonville with the troops headed immediately to St. Johns, reaching the outskirts on the 27th after a 25-mile march. Fort William put up a feeble defense, d'Haussonville gaining the shelter of a hill around 300 yards distant. The garrison was summoned to surrender and the French took possession. De Ternay entered the harbor with his squadron and the French proceeded to "destroy the fisheries and plunder the colony." 3

The first news of the attack reached Sir Jeffrey Amherst, commander-in-chief of the British forces in North America, on the 15th of July. With few complete battalions to draw from, he set about using garrison troops, recovered men from Martinique, and provincials. His younger brother, Lieutenant Colonel William Amherst, was given command of these forces 4, and was to act in conjunction with Lord Colville.

Early the next morning the two remaining light companies led the landing followed by the 1st and 2nd battalions. They were fired upon, but the French gave way to the left companies.

5

Amherst's troops then proceeded to march through a "very thick wood, the path very narrow and several swamps in the way" which afterward opened up, and the British came to Kitty Vitty pond. To gain command of the Kitty Vitty pass, which would enable the landing of future provisions and artillery, Amherst sent the Light infantry over to force the French from a hill, covered by the 1st and 77th Light companies and the grenadiers of the 1st Foot.

A body of French was moving to support the attached post on the hill. Amherst sent Major Sutherland over with the remaining companies of the 1st Battalion. The French outposts retreated back and before dark Amherst decided to halt further operations and take post in the Kitty Vitty area, with the troops lying on their arms. This initial skirmish cost the French ten prisoners with no casualties on the British side except for Captain Mackenzie of the 77th, wounded.

On the 14th Amherst inspected the British position and Lieutenant Colonel Tullikin with Captain Ferguson brought some light artillery and stores around from Torbay. The French took the opportunity to place two small cannon on Signal Hill and started to play on the British encampments. Amherst determined that this threat must be removed as it commanded the whole ground from Kitty Vitty to St. Johns.

At daybreak on the 15th Captain Macdonell's Light Infantry and the provincial Light Troops marched to surprise this new threat. To gain the summit of the hill the two companies had to shove one another up. The French managed to fire several times. Macdonell was ordered to return fire against the three companies of French grenadiers and two of piquets. Captain Macdonell was wounded and Lieutenant Schuyler (60th) killed. Of the men, three or four were killed and eighteen wounded. With what appears to have been the most obstinate of fighting of the entire affair the French had Lieutenant Colonel Belcombe (their second commanding officer) and a captain of grenadiers wounded, with "several" others killed and wounded, and thirteen prisoners taken.

The following day Amherst advanced further to Gibbet Hill and further camp necessaries were landed via Torbay. De Ternay was keen to be gone, and initially 300 men were to be left at Fort William, however a further reinforcement of grenadiers was landed. In the morning a chance fog obscured the harbor and de Tornay wasted no time in slipping virtually under Lieutenant Colonel Tullikin's nose. Tullikin had heard the French busy about their vessels, but could not see any sign of the enemy. Colville called it a "shamefull [sic] flight."

D'Haussonville was now left to his fate, and it didn't look promising, as the 17th, after an "immense deal of work," the British opened up a bomb battery which began to play on the French position that night, with a second battery being made out. The morning of the 18th saw d'Haussonville and Amherst entered into correspondence, the French commander expressing his desire to defend the fort "to the last extremity." He didn't reckon on the reply of Amherst, who didn't "thirst after the blood of the garrison" but warned him of the consequences. With this, the French garrison surrendered. They were "a very fine body of men" wrote Corbett, and Amherst considered them "brave fellows," and d'Haussonville "one of the least troublesome French-men" he'd met. The prisoners were embarked on the morning of the 23rd, 770 men in total. Three companies of the 45th Foot under Captain Stephen Gually and Lieutenant Eyre, 1 NCO and 15 men of the Royal Artillery were left behind by Amherst in garrison.

British losses in this "campaign" were 1 officer, 11 men killed, and 3 officers, 2 NCO's, and 33 men wounded, totaling 50 men.

1 The garrison at Fort William, St. Johns, then consisted of 3 officers and 74 men of the 40th, with a few artillery men under Captain David Rogers. Captain Walter Ross held overall command. "The Loss and Recapture of St. Johns, Newfoundland in 1762" by Major E. W. H. Fyers, Journal of the Society Army Historical Research Vol. XI, 1932.

Ordnance: 4 24 pounders, 6 12 pounders – heavy, 2 12 pounders, 4 6 pounders – light, 4 brass howitzers; Mortars: 2 10 inch, 1 8 inch, 6 Royals, 6 Cohorns

Amherst, Lt. Col. W., Journal, edited by J. C. Webster, in Regt. Annual Sherwood Foresters, 1929.

[Editor's Note: detachments from the following French infantry regiments were in the task force sent to capture St. Johns: La Marine, Penthièvre, Beauvoisis, and Montrevel, according to René Chartrand, Canadian Military Heritage, Vol. II, Montréal, Québec, 1995. Mary Beacock Fryer, Battlefields of Canada, Toronto, 1986, on page 103 also mentions 161 Irish mercenaries who were to form ". . . the core of a battalion to be recruited from among Irish fishermen living in Newfoundland."]

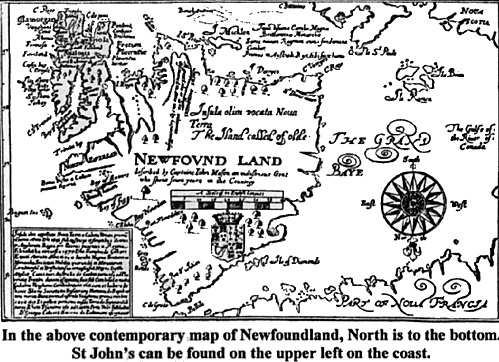

Map

Lieutenant Colonel Amherst arrived at Halifax on the 26th of August, finding that Lord Colville had set off on the 10th. Collecting part of his force, he sailed to Louisbourg, arriving on the 5th of September. By the 7th, Amherst's entire force set off after Lord Colville. On the 11th of September the land and naval commanders at last caught up with each other off Petty Harbor. Amherst found that his original intention of getting into the harbor of St. Johns was impracticable due to French batteries sweeping the entrance. Torbay, further northward, was decided upon for the landing of the troops. The night of the 12th saw preparations for the landing; Colville providing the necessary vessels that were all rendezvoused at HMS. Syren. But the wind blowing hard drove the provincial light infantry out to sea.

Lieutenant Colonel Amherst arrived at Halifax on the 26th of August, finding that Lord Colville had set off on the 10th. Collecting part of his force, he sailed to Louisbourg, arriving on the 5th of September. By the 7th, Amherst's entire force set off after Lord Colville. On the 11th of September the land and naval commanders at last caught up with each other off Petty Harbor. Amherst found that his original intention of getting into the harbor of St. Johns was impracticable due to French batteries sweeping the entrance. Torbay, further northward, was decided upon for the landing of the troops. The night of the 12th saw preparations for the landing; Colville providing the necessary vessels that were all rendezvoused at HMS. Syren. But the wind blowing hard drove the provincial light infantry out to sea.

Notes

2 The squadron consisted of Le Robuste (74), L'Eveille (64), La Licorne (26), La Garonne (26), and La Biche (26). The following statements by Captain Thomas Graves, RN, and Governor of Newfoundland, and Lieutenant Colonel William Amherst (taken from deserters) give the makeup of the land forces. Graves: "They embarked 700 or 800 troops at Brest, being piquets and grenadiers from the different regiments." Amherst: ". . . grenadiers of five regiments, at about 45 men per company, the rest of the Marine . . . making in the whole about 800 men." [Editor's Note: where a number in parentheses follows the name of a ship, the number denotes the number of guns that the ship carried.]

3 J. S. Corbett, England in the Seven Years War, Vol. II, pg. 324. Around 500 craft of all sizes were claimed to be destroyed and damage of a million sterling inflicted before they were interrupted.

4 Table of the British Forces under Lieutenant Colonel William Amherst, Lieutenant Colonel J. Tollikens 45th Foot as second.

From Designation Comments Offs. & Men Officer Commanding New York "Light Infantry" {Recovered men from regiments In West Indies

1st Co.

2nd Co.

3rd. Co. Massachusetts Rgt.103

88

-Cap. J. Maxwell

Cap. C. MacDonnel

Cap. W. BarronHalifax "1st Btn." 3 co's. – 1st Btn 40th Royals

[1 Lt. Co, 1 Gren., & 1 Regular]

2 co's 77th Foot

[1 Lt. Co., 1 Reg.]237

.

158

.

Major P. Sutherland, 77th FootLouisbourg "2nd Btn." 5 co's. 45th Foot 395 Captain S. Gually, 45th Foot Louisbourg "3rd Btn." 5 Co's Hoars Mass. Provincials

1 Co. was detached (see above)520 Lt. Col. J. Winslow Halifax & New York Royal Artillery - 58 Capt. A. Ferguson

5 Lieutenant Colonel Amherst's instructions regarding the light infantry are worth quoting. "Upon the march, the light infantry will cover the front and flanks of the Line, seizing every commanding ground till the line has passed, whenever they may chance to fall in with the enemy they will stand their ground, and never retire to the battalions, which shall always march up and support them."

SOURCES

Corbett, J. S., England in the Seven Years War, Vol. II.

Derby Mercury, Oct. 1762, Dispatches, Amherst and Colville.

Fyers, Maj. E. W. H., The Loss and Capture of St. Johns, JSAHR, 1932.

Gentleman's Magazine, 1762, a French account on p. 363.

Mante, T., History of the Late War in North America, 1772.

Wylly, Col. H. C., History of the Sherwood Foresters (45th Foot), Vol. I.

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal Vol. XI No. 2 Table of Contents

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1999 by James J. Mitchell

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com