The following is a short contemporary account of the famous battle of

Mollwitz discussed by Jim Purky in the Seven Years War Association

Journal (volume VI, No. 1, September 1992). A French translation of the

letter is amongst the State Papers in the Public Record Office, London (code

SP 100/17) and to my knowledge has never been published before.

The following is a short contemporary account of the famous battle of

Mollwitz discussed by Jim Purky in the Seven Years War Association

Journal (volume VI, No. 1, September 1992). A French translation of the

letter is amongst the State Papers in the Public Record Office, London (code

SP 100/17) and to my knowledge has never been published before.

It is written by Rupert Scipio von Lentulus (1714 - 1786) to a General von Diemar, an Austrian cavalry general and colonel of Cuirassier Regiment No. 33 (raised 1702, disbanded 1801). While revealing nothing startlingly new about the battle, the letter is nonetheless a good example of the kind of short reports sent by senior officers to their colleagues. Its tone and style are both typical for the time and for the writer, who was an architypal eighteenth century adventurer.

Born in Switzerland, Lentulus entered Austrian service as an ensign in

the dragoons in 1728. Both elegant and factuous, he claimed descent from a

patrician family of ancient Rome (hence the Roman names which ran in the

family) and once described Moses as "a superb general of infantry" for his

passage of the Red Sea. He probably owed his rise to senior rank more to his

skill as a flatterer than as a commander and was described by a

contemporary as a "tall handsome Swiss, very weak, very vain and very

indiscrete, but, which is worst of all, a servile flatterer and capable of

reporting to his master the greatest of falsehoods, if he thinks they will

please him" [1]

In 1740 he had been attached to the staff of General Browne, who had the

unfortunate job of defending Silesia from Frederick the Great's sudden

attack. While Neipperg's army was collecting in the winter of 1740-41,

Lentulus organized the raids across the mountains which effectively

disrupted the Prussian communications. His most daring plan was an

attempt to capture Frederick at Baumgarten on February 27, 1741 which

failed but left the king greatly rattled. Lentulus later gained fame in Vienna

for refusing to join the Prussian army after the fall of Prague in 1744.

This turned to notoriety when, having left Austrian service the next

year, he accepted a second offer in 1746 and became a Prussian major

general, serving until 1763. Between 1763 and 1767 he returned to

Switzerland to reorganize the Bern militia and after a further twelve years in

Prussian service, eventually became commander-in-chief of all Bern forces.

My thanks are to Mlle Elaine Meyer for her translation of the following

letter which remains true to the rambling style of the original.

In order to communicate to Your Excellency the continuation of our

army's movements, I must not omit to inform Your Excellency very humbly

that after our corps had passed from Moravia to Silesia, the enemy left all the

places which he had occupied in Upper Silesia. He assembled his troops so

that by the 10th of this month he had accumulated a corps of about 25,000

men with which he intended to pass Brieg and march to Ohlau. But after our

corps had similarly advanced and during this march we had met at Grotkau a

party of Prussians of about a thousand men, the majority of which were

recruits, including 20 officers, and having made them prisoners of war (our

hussars having captured some on the 8th and 9th, officers as well as

soldiers) [2], we carried on marching

until we reached a small town situated beyond Brieg towards Mollwitz where

on the 10th at midday we sighted the enemy in full march, without being able

to form a firm opinion of his strength [3].

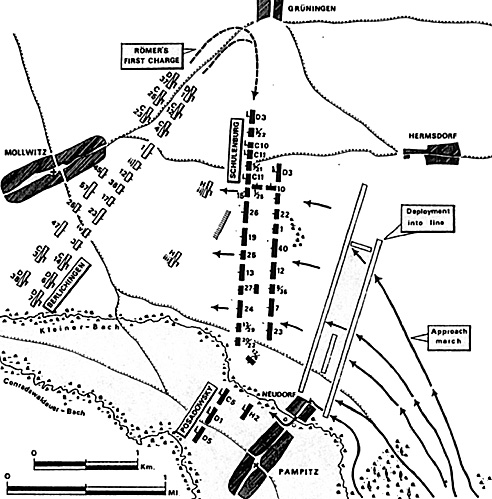

We formed up on each side and in front of the village of Mollwitz, and the

cavalry of our left wing attacked the enemy's right.

This was done with so much success that their aforementioned wing

was thrown totally into confusion and we were expecting the victory to be

ours. So much so that the king must have retired very hastily to Lowen

castle and, in addition, our cavalry had seized all but one of the enemy's

cannon which had been set up in front of their left wing

[4]. But when our cavalry started galloping along the

enemy's front line, with a view to penetrating their left flank and putting that

wing also to flight, they unfortunately discerned that that wing was situated

in an area covered by marshland and therefore could not approach it [5]. Having seen our left wing deprived thus

of its cavalry, the enemy reformed in such a way that not only did it retrieve all

its cannon, bar one, but by their heavy fire they forced our corps gradually

back until we had to withdraw entirely and leave the battlefield to them,

whence they did not pursue us further.

Total victory would have been ours if, to take advantage of the initial

confusion amongst the enemy, our commander-in-chief had been properly

supported and his orders duly executed. Having said that, the enemy cannot

boast to any greater advantage than having taken the battlefield and

captured two cannon that we could not take with us anyway, not having

any good horses to pull them. As regards the enemy's losses, from all the

reports we have, they must have lost more than 8,000 men and added to that

there is their enormous and extrordinary continual desertion. On our side,

we estimate our losses at only 4,000 men and I even believe them to be

below that [6]. The reason is that, first,

we only saw very few dead on the battlefield, and I personally rode over it

twice; and second, every hour sees the return of wounded men and

marauders that were thought to be lost.

Amongst our dead are Generals Romer and Goldi, and amongst the

wounded are Brown, Grunne, Birckenfeld, Kheul, Franckenberg and myself,

although luckily the shot I received entered my right breast obliquely and I

hope, with God's help, to be healed soon enough. For that purpose I intend

to go to Glatz tomorrow, our commander-inchief having also ordered me

there to take the necessary measures in that County, as well as in the

Kingdom of Bohemia. Anyway, all I wish for now is to have the honour of

being under the command of Your Excellency during this campaign,

considering that it will probably last a while longer; this due to the enemy

now gathering troops near Brieg with a view to besieging that place.

Meanwhile our corps will be scattered in the surrounding areas near here in

order to rest and recuperate. As far as the regiment of Your Excellency is

concerned, I've heard that it has already entered Silesia which means that it

will be able to be here soon.

I am etc...

[1] Mitchell, the English

ambassador to Prussia, to Keith, H.M. representative in St. Petersburg, 10

February 1762, in A. Bisset (ed), Memoirs and Papers of Sir Andrew

Mitchell, K.B. , (2 vols., London, 1850), 11258-259.

Austrian War Archives, Oesterreichischer Erbfolgekrieg 1740-

48, (9 volumes., Vienna 1896-1914), 1.

Translation of a letter to H.[is] E.[xcellency] M. le General de

Diemar from M. le Baron de Lentulus, dated Neisse April 13,1741

Footnotes

[2] The force actually consisted

of 800 "Weisskittels", unarmed recruits so called because of their long white

coats, who were on their way to work at the siege of Neisse, along with a

small escort. The Weisskittels were later exchanged following a cartel signed

at Grottkau on July 9, 1741 and used to expand the new Briegisches

Garrisons-Regiment formed from the former Austrian garrison impressed

after the surrender of Brieg (May 4, 1741). (GR no. VI). Jany, 1131, 39-40.

[3] According to the most

plausible estimates, the Prussians actually totalled 16,800 infantry, 4,000

cavalry, 500 hussars and 300+ artillery crew with eight 12-pounders, two 24-

pounders, six 18-pound howitzers and about thirty-four battalion pieces.

The Austrians numbered 10,000 foot, 8,000 heavy cavalry, 500 hussars and

400 artillery crew with eight 3-pounder regimental guns, four 3-pounder field

pieces, four 6-pounders, two 12-pound howitzers and one small petard.

Jany, 1132, and GGS 1392.

[4] These cannon had been

positioned 100 to 150 paces in front of the Prussian infantry. As the

Austrians charged the Prussian teams fled and all the heavy and some of

the battalion pieces were captured. The Austrians turned them round and

fired a salvo at the Prussian foot (the cannon were already loaded). They

then spiked them and managed to drag off two heavy pieces (probably

howitzers as these were the easier to move) and two lighter ones. The

Prussian artillery were subsequently ordered not to advance beyond 50

paces in front of the infantry and to retire to spaces between the battalions

if the enemy attacked.

[5] The Prussian cavalry were

actually on the other side of the marshy Klein Bach stream. The Austrian

cavalry had ridden along the Prussian front in pursuit of the part of the

Prussian right, including Frederick himself who had been swept along with

the fugitives. The rest of the Prussians had fled the field. The pursued

Prussians either crossed the stream and joined their cavalry left (wing), or regrouped behind the Prussian infantry.

[6] Prussian

losses were actually 4,850 (including 191 officers) killed,

wounded and missing. The Austrians lost 4,551

(including 223 officers) killed, wounded, captured and

missing, along with 1,661 cavalry and 58 artillery horses.

Fourteen infantry and three cavalry standards were lost,

as well as six cannon, one howitzer, the petard and a pair

of copper kettledrums.

Other Sources Consulted

C. v. Jany, Geschichte der Konglich Preussischen Armee vom 15.

Jahrhundert bis 1914 , ( 4 volumes, Berlin, 1928-29; reprint Osnabruck,

1967), 11.

Prussian General Staff (GGS), Der Erste Schlesische Krieg 1740-

42, (3 volumes, Berlin, 1890-93), 1.

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal Vol. X No. 4 Table of Contents

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1999 by James E. Purky

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com