The Russians followed the common European practice during the Seven Years War of assigning light artillery directly to infantry regiments (which in Russian service consisted of two field battalions). Each regiment received two 3-pound cannon. Infantry regiments also had 6-pound mortars, but sources vary as to how many. Some indicate that they began the war with four which were soon reduced to two, and some say eight which was soon reduced to tour. In any event, the complement of artillerymen for a Russian infantry regiment was: 1 commander, 5 canoneers, 10 fusiliers, and 15 gun handlers. A total of 31 men.

The reason for the reduction in the number of mortars after the war began is the fact that the unit's regimental artillery was dispersed up and down the front. This meant that the commander who wore an infantry uniform but was assigned from the artillery service could not personally supervise the major portion of the guns. Mention is made that after 1758, the infantry regiments received small-caliber unicorns, and also that some infantry regiments had Shuvulov howitzers instead of mortars.

Personally, I would question whether the 6-pound mortars regularly occuppied the infantry in the field. Johann Tielcke, a Saxon artillery officer in Russian service, from whose observances much of the information in this article is drawn, mentions only 3-pound cannon as regimental artillery during the campaign of 1758.

When General Fermor invaded East Prussia in 1758, he brought along with him a considerable artillery contingent consisting of 242 field guns plus numerous regimental guns. Eventually, trailing an immense supply train behind it, the Russian army moved through East Pomerania and approached the banks of the Oder River.

There, in camp, on August 14, 1758, the Russian army was attacked by the Prussians in the exceedingly bloody battle of Zorndorf. The regular infantry and cavalry of Fermor's army would have numbered some 89,000 men had the units been up to strength, but this was not the case. A more realistic number would have been 60,000 regulars and about 16,000 Cossacks and Kalmuks, but many of these were sent home by Fermor for indiscipline.

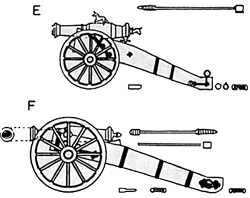

Russian 12-pounder unicorn howitzer (figure E) and 12-pounder Shuvalov howitzer. Courtesy of Christopher Duffy, from The Army of Maria Theresa.

Russian 12-pounder unicorn howitzer (figure E) and 12-pounder Shuvalov howitzer. Courtesy of Christopher Duffy, from The Army of Maria Theresa.

Not counting the regimental light artillery, the artillery train of Fermor's army consisted of the following:

-

12-pound cannon 20

8-pound cannon 26

6-pound cannon 10

Mortars 6

Shuvalov Howitzers 50

Common Howitzers 20

96-pound Unicorns 2

48-pound Unicorns 12

24-pound Unicorns 30

12-pound Unicorns 20

3 & 6 pound Unicorns 28

3-pound Unicorns and dragoons 18

Total 242

It should be noted that the list on the previous page included the field artillery of the Corps of Observation. a separate infantry establishment, some 20 musketeer battalions and 32 grenadier companies which accompanied Fermor. Also, not all of the artillery would be concentrated at one time, some of it being detailed to detached forces.

Artillery carriages were painted red during the Seven Years War and gun barrels were made of brass. After 1792, the carriages were painted green.

Russian Artillery

What should be obvious from the list of Russian field artillery for the 1758 campaign is that the Russian artillery was absolutely unique among the artilleries of Europe in that fully 75% of it was howitzer, rather than cannon, in type. The common howitzers were short-barreled pieces similar to those found in other European armies. I have been unable to determine their exact calibers, but Tielcke stated that the Russians favored the larger calibers.

The unicorns had sub-diameter chambers at the end of the bore for accepting the powder charge (in the case of unicorns, the chamber was conical in shape.). And the principal projectile of the unicorn was the explosive shell. Thus, by definition, unicorns were howitzers.

However, they had a very special feature not found in common howitzers. They were long-barrelled. For those whose artillery terminology is rusty, "caliber" is defined as the diameter of the bore of the gun or howitzer. The barrel lengths of common howitzers varied, but generally they fell within 2x the caliber of the howitzer in British service, or l.Sx the caliber in French service. The barrel legnths of unicorns were, however, 10x their calibers.

The following barrel lengths are approximately correct for the various calibers of unicorns (I say approximately because I have had to use equivalent measurements out of Muller, but the variation would be slight):

-

3-pound unicorn, 2'6"

6-pound unicorn, 3'0'

12-pound unicorn, 3'9"

24-pound unicorn, 4'9"

48-pound unicorn, 6'0"

96-pound unicorn, 8'4".

In theory, the unicorn combined the best offensive qualities of gun and howitzer. Increasing the barrel length of the weapon increased its point-blank range. The point-blank range refers to how far the projectile could be thrown on a flat trajectory (below man-height) to its first bounce. This is important to cannon firing solid shot as the lethal effect of the shot is mainly derived from the fact that it will theoretically kill anything in its path for the extent of its point-blank range. By increasing the point-blank range of the unicorn, its shell could act just like a solid shot until it caused additional damage by exploding.

Theory vs. Practice

Unfortunately for the unicorn, what sounds like terrific theory sometimes works far less well in actual practice. There was a problem with unicorns, and it derived mainly from the sub-diameter chamber for seating the powder charge. It is not difficult to seat the charge in the chamber of a common howitzer with its short barrel.

However, seating the powder charge properly in the chamber becomes more and more difficult and time consuming as the length of the barrel increases. As the residue of previous discharges builds up, the problem gets worse and worse. Thus the unicorns tended to be slow-loading weapons and much of their utility was negated by a poor rate of fire. The larger calibers were also extremely ponderous in weight and maneuvered only with difficulty.

It is probably a good place to clear up some of the confusion which surrounded the calibers of Russian artillery. Statements about very powerful Russian artillery of 1, 1.5 and 2 pound caliber are often encountered. At first glance, this sounds preposterous. During this period, complaints among artillerymen that 3 and 4 pound battalion guns were too light to be really effective were not uncommon. The confusion about Russian artillery pertains to the special nature of the unicorns.

Shot Weights

Guns or cannon are named after the weight of iron round shot that they throw. Thus, a 3-pound gun can throw an iron shot weighing 3 pounds. Its bore is large enough to accomodate an iron that size plus a little extra for windage. Howitzers, however, were not named for the weight of iron shot that they could throw, but instead were named for the weight of stone roundshot they could throw. Of course, howitzers didn't actually throw stone shot. This was an archaic hold-over from old-fashioned mortar measurement, the howitzer being an adaptation of the mortar, differing mainly in its type of carriage and position of its trunnions. The English very sensibly named their howitzers after their calibers.

Thus the English 5.5" howitzers which accompanied the two British "Light Brigades" at Minden.

The French Valliere system made no provision for howitzers. However, the French recognized their utility and employed them on an ad hoc basis, also calling them after the measurement of their caliber. Reference is made to French.use of 6" and 8" howitzers during the period in question. The Germans and the Russians persisted in calling howitzers after the weight of stone shots. Thus, for example, the 7-pound howitzers in Prussian and Austrian service could theoretically throw a stone roundshot weighing seven pounds.

B<>Problem with Unicorns

The problem with unicorns was, simply, what system of measurement to use. True enough, the unicorn was a howitzer. But like a gun, it had a long barrel. What happened was that both systems were used, and this created a great deal of confusion, at least for the modern student of the period. In the list of the Russian artillery train for 1758 (given in this article and drawn from Tielcke) the iron shot system is used, and the unicorns are rated in the same fashion as cannon.

Stone is far less dense than iron. A stone roundshot weighing on pound had a diameter of about three inches; a one pound iron roundshot had a diameter of only two inches. The Saxon artillery which had both a cannon and a howitzer rated as 8-pounders effectively illustrates the difference in bore diameters (calibers) when the stone and iron system was used. The Saxon 8-pounder cannon had a caliber of about four inches. The caliber of the Saxon 8- pounder howitzer was, however, about 6.4 inches. As stated, a howitzer throwing a 1 pound stone shot would be throwing a projectile of about 3-inches in diameter.

An iron roundshot of about a 3-inch diameter would weigh about 3 pounds. Thus the same unicorn, according to whether the stone shot or iron shot measurement was used would be, respectively, a 1-pounder or a 3-pounder.

Tielcke states that when it was desired to fire unicorns at extreme ranges, the tubes were placed on special carriages that resembled ship carriages without the trucks. They were not very accurate when employed in this fashion, however.

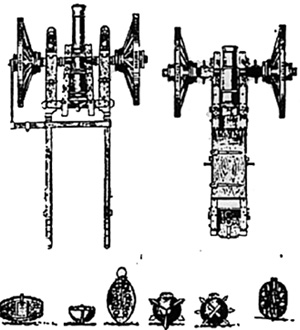

Another interesting type of unicorn was the little 3-pounder especially

employed with the dragoons and horse grenadiers. Placed on an axle-

tree of this piece on either side of the unicorn tube was a little

coehorn mortar of 6-pound caliber (iron measure, not stone).

Another interesting type of unicorn was the little 3-pounder especially

employed with the dragoons and horse grenadiers. Placed on an axle-

tree of this piece on either side of the unicorn tube was a little

coehorn mortar of 6-pound caliber (iron measure, not stone).

At right, light field gun (left) with coehorn mortar set on the brackets of the carraige, and, conventional half-pud howitzer (right).

A word should probably be said about so-called Russian horse artillery, however. Russian cavalry was very poorly trained. In fact, it was not until the Russians entered Germany were they able to procure decent mounts for their cavalry, as the homeland did not produce suitable mounts.

Thus, these little unicorns were to support poor cavalry and

probably had an adverse effect on what little mobility in formed

bodies the cavalry did have. This artillery is not to be equated with

the horsed artillery or artillerie volante of Frederick which was a new

innovation in mobile artillery able to be quickly deployed at critical

points on the battlefield.

Shuvalov Technology

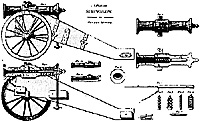

Large Shuvalov Howitzer illustration (slow: 70K)

The Shuvalov was named after Piotr Shuvalov, the Russian

MasterGeneral of ordnance. It was very much his baby, and he

wasn't at all interested in hearing criticism of it. The Shuvalov was

unique in that it had an oval rather than round bore configuration (see

illustration in this article). On the horizontal plain, it had a diameter of

a 3-pounder (about 3 inches). On the vertical plain, it had the

diameter of a 2-pounder (about 7 inches).

The Shuvalov was designed mainly as a cannister-firing

weapon. The theory behind the oval bore is apparent. By

compressing the vertical diameter, less of the cannister pattern will be

expended over the head of the target or into the ground before it.

Similarly, by expanding the horizontal diameter, the cannister will be

able to hit targets over a greater lateral spread. Rating the Shuvalov

in terms of caliber is quite a trick. As far as I have been able to

determine there was only one caliber of Shuvalov. Tielcke calls it a 3-

pounder after its vertical diameter. I suppose one could just as easily

call it a 2-pounder after its horizontal diameter.

Christopher Duffy mentions, in his Army of Marie

Theresa, that a battery of Shuvalov howitzers was presented to

the Austrians in 1759. Duffy calls it a 12-pounder, using a source which to date I

have been unable to obtain. I would speculate, however, that it is

certainly the same gun, as Tielcke refers to the 3-pounder he

describes as the same piece sent to the Austrians. Probably, calling it

a 12-pounder was a compromise between the 3 and 24-pounder

calibers of the single Shuvalov. Given the oval bore, as I stated

earlier. artillery terminology is quite fractured, and there is no one

suitable way to rate this howitzer.

Large illustration (slow: 70K)

They concluded that the effective range of the pieces was too short and that the carriages were unduly heavy for reasons explained in this article. He also notes that Fennor and

Tielcke had reached the same conclusion by the end of 1759.]

The Tielcke drawing of the Shuvalov howitzer shows a

thoroughly modern-for-the-period elevating screw which worked

directly on the barrel. Interestingly, Duffy's illustration shows the

Shuvalov with what appears to be a simple elevating wedge. I do

have a speculation to explain this seemingly contradictory

information. Sometime later, when the English finally introduced the

modern elevating screw which acted directly on the barrel (after first

trying out a less satisfactory screw which ran through the cascabel

button) they didn't include the new screw on larger caliber guns

because the tubes were simply too heavy for the screw to work

effectively.

For reasons which will be explained, the Shuvalov was an

extremely heavy piece. I would guess that the modern elevating

screw formed part of its original equippage, but in practical usage,

the gun-tube was found too heavy for it, and it was dispensed with in

favor of the simple wedge.

As previously stated, the Shuvalov was considered by the

Russians to be a secret weapon of devastating potential. The "Secret

Howitzer Corps" was a separate formation in the artillery

establishment. Officers of the regular artillery were not allowed to

even approach the Shuvalovs, much less inspect them. Whenever the

howitzers were not in actual use, caps were kept locked over their

muzzles to disguise their oval interior construction. Another step

taken to disguise the bore and this had unfortunate results in terms of

reducing the effectiveness of the Shuvalov.

Obviously, if the bore is oval in shape, to make the gun as light as possible, the exterior shape of the barrel should be oval as well. It was not. The exterior was round like any other gun or howitzer.

Thus, it gave no hint of the oval bore, but at the cost of adding a

tremendous amount of superfluous metal to the weight of the tube.

The Shuvalov barrel was about 4' 2" long with the outside barrel

dimension of a 24-pounder, but with much more metal than a 24-

pounder of the same barrel length. It was an extremely heavy piece,

ponderous and difficult in the extreme to maneuver. In addition, it

suffered from the problem of having, as a howitzer, a sub-diameter

chamber combined with a long barrel. Thus, it was slow-loading as

well as being very awkward to move. At Zorndorf, the Shuvalovs

managed to get off only one round of fire before they were over-run

by Prussian cavalry. Of the 50 pieces in Fermor's army, 17 were lost

at that battle alone.

The limber for the Shuvalov carried 40 cartridges and 40 loads.

As mentioned previously, the preferred ammunition was cannister.

There were two types of cannister. The first carried 168 2-ounce

lead balls and was rated effective up to 300 paces. A heavier case-

shot was also employed. A single load carried 48 7-ounce lead balls,

and it was rated effective up to 600 paces. The Shuvalov could also

fire grape-shot which consisted of seven 3-pounder iron roundshot

with a claimed effectiveness of 1,200 paces. An explosive shell could

also be fired, but because the oval configuration of the barrel

necessitated that it be flask-shaped, rather than round, it was neither

long-ranged nor very accurate. Finally, an incendiary shall or carcess,

also flask-shaped, could be fired.

Anyone who looks into the question of Russian artil1ery in the

Seven Years War soon discovers a wide variation in estimates as to

its effectiveness among various sources.

We read, for example, that the Austrians "begged" for some of

the new Russian artillery. As Duffy demonstrates, this was hardly

the case. The Austrians were hardly impressed, but they did not

want to offend their allies and agreed to give the ordnance a test.

The French were also offered some Shuvalovs and unicorns, but

turned them down. The Russians, at least the head of the artillery

department, were very impressed with the quality of the artillery. It

seems, unrealistically so.

I think what has happened is that some writers have taken the Russian propaganda about the quality of their guns uncritically. [Editor: generally so do wargamers who own Russian SYW armies.] They have taken statements from the Austrians, which were politically motivated compliments, rather than true opinions.

The Russian artillery was apparently not nearly as good as it

has sometimes been represented. In fact, it appears that it was

rather ineffectual compared to that of the Austrians or Prussians.

The particular problems with the unicorns and Shuvalovs which

made up the bulk of the Russian artillery have been touched upon in

this article. And there are contemporary observances by officers

who had occaision to observe it as to the unwieldiness of Russian artillery.

There was another factor which mitigated against artillery effectiveness in the Russian army. The gunners themselves were apparently exceptionally brave. We read accounts of gunners staying by their guns long enough to be over-run not only by Prussian cavalry, but even by Prussian infantry. However, the Russians apparently never learned how to mass their artillery and deliver a concentrated fire on vulnerable pants of the enemy line. Rather, Russian artillery was dispersed up and down the front which dispersed it lethal effect.

[Editor: Frederick employed a grand battery of 55 guns at Burkersdorf on July 21, 1762; but for the most part, this tactic was not commonly used during the Seven Years War. So

we should not be too critical of the Russians in this regards.]

Finally, there is the question of howitzers. As General Hughes

asks rhetorically in his provocative book Fire-Power, why,

if howitzers were as effective as cannon were they not found in far

larger proportion to cannon in European armies, aside from the

Russians? In effectiveness, howitzers are much more vulnerable to

irregularities of terrain than are cannon. The latter can make good

use of dccochet effect given expedenced gunners. The dccochet

effect ofcannister is severely limited, and howitzers being lower-

velocity weapons are shorter-ranged to begin with than cannon.

We can appreciate that the great reliance on howitzers in

Russian service, as did they Russian custom of deploying infantry in

massive squares, was the heritage of interminable wars against the

Turks on essentially level steppe terrain. The main offensive Turkish

arm was masses of irregular horse on which cannister could be used

to good effect. The pyrotechnic effect of shell bursts was also

undoubtedly of great psychological value.

Much has been written about the vulnerability of the Russian square to European armies equipped with artillery. At Zorndorf a single Prussian ball rendered 42 men in a

Russian grenadier battalion hors de combat. And this, I

think, was the essential fault of the Russian artillery during the Seven

Years War. The Russians were forced to fight with types of guns

and types of tactics (dispersal of fire) against a type of enemy that

neither the artillery nor its tactics had been designed for.

The main source used for this article is An Account of

Some of the Most Remarkable Events of the War Between the

Prussians, Austrians and Russians, from 1756 to 1763, by

Johan Tielcke. Translated from the second German edition. London

1787. Two volumes. In addition, I have used W. Zweguintzov's

L'Armee Russe , Paris 1967. This is an excellent distillation of

the massive 30 volume work on the weapons and uniforms of the

Russian army by A.V. Viskovatov, published in St. Petersburg, 1844

1856. The Slavonic Division of the New York Public Library has a

complete set. However, it being in Russian, it is not linguistically

accessible to me. Any member with a working knowledge of Russian

and access to this work could undoubtedly turn up much useful

information to share with the members of the Seven Years War

Association

[Editor: are there any members willing to work on this

project? If so, write me a letter and we can discuss. The SYWA is

willing to compensate you for some of your expenses.]

In addition, I have also used Volume II of Lilane and Fred

Funcken's L'Uniforme et Les Armes des Soldats de la Guerre

en Dentelle. They seem, however, to rely completely on

Zweguintzov. Also used was Russian infantry Uniforms of the

SYW by Pengel & Hurt. They use Zweguintzov as well as

Die Heere der Krieggfuhrenden Staaten 1756-1763

series by Friedrich Schirrner and articles from "Des Spontoon"

magazine by Gunther Ellfeldt. Christopher Duffy's The Army of

Maria Theresa [Editor: and Russia's Military Way to the

West.] and Thomas Carlyle's History of Frederick the

Great have provided useful background information (the latter

introducing me to Tielcke and suggsting what a worthwhile source he

would prove to be).

Finally, three books have proved very helpful on the general subject of artillery, and as they are available in recent reprints, are recommended as excellent additions to the library of any student of 18th Century warfare. They are: A Treatise of Artillery 1780 by John Muller, 3rd Edition of the work first published in 1757 (Museum Restoration Service, Bloomfield, Ontario, Canada 1977); A Treatise of Artillery, by Guillaume LeBlond, 1746 English translation of a standard French work (Museum Restoration Service 1970); and A Universal Military Dictionary by Capt. George Smith, 1779 (Museum Restoration Service, 1969). The latter is especially useful in gaining an understanding of contemporary usage of 18th

Century technical terms.

[Editor: I would add Hughes' Firepower book which was reprinted about a year ago and is a must-have book for any military historian or wargamer. In addition, the two

Osprey books on the Russian Army of the Seven Years War and Duffy's book Russia's Military Way to the West had not been published at the time Steve wrote this artick, which by the

way, appeared in the very first issue of the Seven Years War Society Newsletter , as our organization and publkation were first known. This was circa 1981. Steve was our first

editor, followed by Bill Protz, and then me.]

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. If the Russian unicorns with their mixture of cannon and howitzer attributes strained contemporary artillery terminology in terms of rating their calibers, then another type of Russian artillery fractured the artillery terminology altogether. This was the Shuvalov,

the so-called "secret" howitzer. It was very much the Russian national secret weapon and acquired an awesome reputation for destructiveness, which as practical battlefield experience was to demonstrate, it was by no means capable of living up to.

If the Russian unicorns with their mixture of cannon and howitzer attributes strained contemporary artillery terminology in terms of rating their calibers, then another type of Russian artillery fractured the artillery terminology altogether. This was the Shuvalov,

the so-called "secret" howitzer. It was very much the Russian national secret weapon and acquired an awesome reputation for destructiveness, which as practical battlefield experience was to demonstrate, it was by no means capable of living up to.

[Editor: Duffy mentions that the Austrians tested a battery of 4 secret howitzers and 2 half-pud unicorns, a pud being the equivalent to 40 pounds, thus the unicorns were 20-pounders.

[Editor: Duffy mentions that the Austrians tested a battery of 4 secret howitzers and 2 half-pud unicorns, a pud being the equivalent to 40 pounds, thus the unicorns were 20-pounders.

Notes on Sources

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal Vol. X No. 2 Table of Contents

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1998 by James E. Purky

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com