The Decree of

18 February 1808

A Tactical Reorganisation

or An Expansion

of the French Army

By G. F. Nafziger

| |

Napoleon issued hundreds of decrees during the eleven years of his rule, but few were more important than the decree he issued on 18 February 1808. Superficially this decree is a simple reorganisation of the infantry battalion and regiment. In fact its significance and impact was far beyond that.

The Imperial Decree of 18 February 1808 is tangible evidence that Napoleon intended to embark upon a major military campaign of conquest. It was also the process by he rebuilt his infantry by three years of campaigning and it was a tactically innovative reorganisation.

Although this decree was seemingly minor adjustment in an administrative and tactical military formation, the infantry regiment, in fact it had an incredibly significant impact beyond what the casual observer might suspect. Indeed, this decree was an administrative masterpiece reflecting the agile mind of the creator of the Code Napoleon.

Prior to 1808 the organisation of the French infantry was set by the Consular Decree of 24 September 1803 which reduced the number of line and light (legere) regiments to 90 and 26 respectively. Several very under strength regiments were disbanded by this decree and their troops were incorporated into the remaining regiments. Despite this move towards standardisation, regiments had two, three, or sometimes four battalions. The internal structure of a regiment was also revised, but there still remained some variation because of the inconsistent number of battalions per regiment. [1]

This organisation gave a two battalion regiment a total strength of 2,162 men when on a war footing, but in peacetime many of the men stood down and the regiment would have only 1,375 men. For a three battalion regiment the wartime strength was 3,234 men and for a four battalion regiment it was 4,306 men.

The Decree of 19 September 1804 directed that a voltigeur company be raised in every French line battalion. In each light or line battalion this company replaced the 2e compagnie. [2]

The numbers of companies of the battalion was standardised through the light and line infantry, but the numbers of men in the different companies were still organised differently based on the companies' functions. [3]

Shortly after the Treaty of Tilsit, which was signed on 9 July 1807, Napoleon began to consider reorganising his infantry. Some minor formations assumed the six company formation before the issuance of the Decree of 18 February 1808 probably as a experiment to assure the functionality of what the decree would mandate.

When issued, the Decree of 18 February resulted in a massive reorganisation of the French infantry and reduced most battalions from a nine company organisation to a six company organisation. The use of converged grenadier battalions was disappearing and, for tactical reasons, the battalion needed to have an even number of companies.

This decree reorganised the infantry regiments with a uniform five battalions each. The fifth battalions were the depot battalion while the first four were "bataillons de guerre" (war or field battalions). Each of the field battalions of a line regiment had six companies: one of grenadiers (elite infantry), one of voltigeurs (light infantry) and four of fusiliers. A legere regiment had one company of carabiniers, one of voltigeurs and four of chasseurs. The depot battalions always consisted of four fusilier (or chasseur) companies. [4]

This organisation gave each regiment a total of 3,970 men, including 180 officers and 3,862 non-commissioned officers and men. [5]

There were some problems with this reorganisational process. In many regiments it was not possible to organise the 4th Battalion because the four fusilier companies required to form it were with provisional regiments then serving in Spain and the two elite companies were serving with Oudinot's division. In addition, the 32e Regiment legere was provisionally maintained with a nine company organisation.

In addition, the regiments under Junot in Portugal were actively involved in a campaign and retained the old nine company organisation until they could be pulled back and reorganised.

There were three regiments serving in the colonies, the 26e, 66e and the 82e Regiments de Ligne. Because of their assignment and different organisation the process of their reorganisation was quite different, but aimed at the same goal. [6]

This reorganisation was to be completed on 1 July and was to result in the following organisation:

The First Result

In order to assess the impact of these reorganisations we must look at the impact it had on the entire infantry organisation of the French army. At the end of 1800 the French infantry, exclusive of foreign troops, had consisted of:

This force had a theoretical total strength of 10,128 company officers, 47,264 company NCOs and 330,004 men. It should be recognised that the actual strength of these units was far below that. On 2 May 1808, with the invasion of Spain well underway and after the reorganisation, the French infantry establishment stood as follows:

In gross terms this is a total of 122 regiments with 4 field battalions, or a total of 488 field battalions. This comes to a total of 8,784 company officers, 40,992 company NCOs and 360,144 men. Adding in the field companies of the 32e Regiment legere we have a total of 8,865 company officers, 41,370 company NCOs and 362,448 men. In addition, there were 122 depot battalions which had a total of 1,464 company officers, 6,832 company NCOs and 60,024 men. This brought the theoretical total of French line infantry to 10,329 company officers, 48,202 company NCOs and 422,472 men.

This decree was the most sweeping reorganisation of the infantry regimental organisation during the Imperial period. It formally established and uniformly structured the depots which were critical in the continuing organisation and support of the entire French infantry organisation.

It also reduced the size of the battalions to a more manageable size, that is, providing a smaller organisation for the battalion and regimental commanders to control, thereby improving their ability to control their men. However, this was offset to some indeterminate degree by

the dilution of the number of company officers to enlisted. This reorganisation also had many other implications most of which were tactical in nature.

The first and most significant implications of this decree are found in the distribution of the cadre and the number of soldiers per cadre member. [7]

The decree had the effect of reducing the ratio of cadre to men has a negative impact on morale, discipline and tactical control. Why did Napoleon do it?

The true impact of Napoleon's 1808 reorganisation is revealed here. The principal change is in the ratio of soldier to officers and the ratio of men to NCOs. It should be remembered that Napoleon's armies just went through three years of heavy campaigning (1805, 1806 and 1807). The losses in all personnel during those three years must have been heavy. However, losses in officers and NCO are far harder to replace than losses in soldiers. The only way this disparity in numbers could be quickly eliminated was by reducing the quality of the officers. This was definitely done and had negative effects.

A survey of Martinien's accounts of officer losses during the period 1805-1807 shows 530 wounded and 239 dead officers in the first 25 line regiments. Expanding this to cover all 140 line and legere regiments during this period provides us with an estimate of 2,968 wounded and

1,339 dead regimental officers of all grades. However, the ability of the wounded to return to combat was limited by the fundamental surgical practice of the day - amputation. It would not be too unrealistic to assume that at least 50% of the wounded would never return to combat. This would allow 50% to return to duty eventually.

The assumption that 50% of the wounded would never return to their regiments brings the total number of officers estimated lost to the French army to approximately 3,000 men. It should also be considered that the losses amongst the non-commissioned officers should have been proportional.

The pipeline of new officers, for financial reasons, must be established to balance the normal loss of officers from the normal level of attrition due to disease, old age, retirement, desertion, and some combat losses. As Martinien's study is solely an accounting of casualties in battle, it does not include those officers who died of relatively "natural causes," or were lost to the service because of "natural causes." This strongly implies that Napoleon's officer replacement system in 1808 was desperately behind in its effort keep the infantry cadres up to strength.

There were 10,128 company officer billets in the army in the period 1805-1807. The elimination of these probable casualties from this force represents a loss of 22%. This would have left him with 7,899 officers. The reorganisation required 8,865 officers, 966 officers more than he should have had, based casualty estimates. This would suggest that Napoleon was going to have to take every step possible to find enough officers to complete the reorganisation of his army. He was already nearly a thousand short.

Many of the historians who discuss the 1809 campaign speak of the French army being heavily filled out with new draftees. The figures generated so far show that there were 32,444 new draftees in the army lead by 966 new officers. If one assumes that there were casualties amongst the soldiers equal to those among the officers, 22%, there would have been 76,000 casualties. We can then draw the conclusion that there were potentially 105,000 new draftees in the French infantry in 1809. This would certainly reduce the overall quality of the army.

Dilemma

Napoleon faced a dilemma. In 1808 he was at war with England and in Spain, while Austria was a growing threat that would bloom in 1809. With the hindsight of historical perspective one can reasonably argue that Napoleon had grandiose ideas and may well have been dreaming of truly emulating Charlemagne. To do this would have meant recombining all of western Europe under his control in a continual war of conquest. The wars with England, Spain and Austria, as well as the recreation of an ancient empire required a strong army and an army can only be strong if it has sufficient cadres.

The dilemma is this. Where does Napoleon find the necessary cadre to expand the army he needs to prosecute these wars? Theoretically, it took two years and a formal school at Fontainbleau to train a corporal. This was not always observed, as one can readily find when exploring the French preparations for the 1812 campaign. It should also be noted when Napoleon learned of the efforts of various Marshals to short cut the requirements for promotion to corporal and other NCO grades he most emphatically stopped the practice.

Further time in grade was required to train fourriers, sergeants, and sergeant-majors. Many, though not all of the officers were drawn from the ranks of senior NCO's after further years of service. Various academies provided junior officers for the army as well.

The Imperial Guard also was utilised as a source of NCO's and officers. Soldiers in the Guard ranked one rank higher than their equivalents in the line. That is, a private in the Guard ranked as a corporal in the line. This was justified by the requirement to be a veteran of a specified number of campaigns and to have a specified number of years service. The Guard was intensively used as a source of NCO's in the spring of 1813 when Napoleon rebuilt his army, but in 1808 the Imperial Guard was too small to provide many cadres.

Despite the various sources available to Napoleon, the system was not equipped to produce large numbers of officers and NCO's in a hurry. Plainly it was easier to draft and train soldiers than it was to train NCO's and officers. The only solution was to reduce the ratio of cadre to soldiers. With this in mind, as one reviews the impact of Napoleon's reorganisation of 18 February 1808 it becomes obvious that Napoleon made this reorganisation for the purpose of bringing his army back up to strength and to provide a basis for its expansion. This is further

supported by the formal establishment of a depot battalion for every regiment which would and did train replacements for the field battalions. It is very difficult to quickly expand or replace losses without a formal, organised system of generating trained replacements.

This is simple solution, but it should have been plagued with problems. The army was expanding and there were insufficient cadres to control the mass of new man in the manner in which they had previously been controlled. Despite this there were no major problems. As stated earlier, the "draftees" fought very well against the Austrians in 1809.

Why did they do so well?

To begin with the army had a very large percentage of very able veterans who had campaigned from 1805 through 1808. Secondly, a formalised depot system had brought order to the chaos of training. Finally, the older and now disbanded system, was based on the needs of the Revolutionary Army. The new Imperial Army had a decidedly different nature and its needs were different.

There was a significant structural impact resulting from the Decree of 18 February 1808. Napoleon succeeded in rebuilding and expanding the number of tactical elements in his army, which allowed him to project power over more territory. It allowed him to overcome the cadre losses in three years of campaigning. It allowed him to standardise the infantry organisation and as any logistician knows, standardisation is one of the keys to success. It also provided Napoleon with a formal depot system that would produce a regular stream of trained soldiers

for his armies.

The impact of changing the size of the infantry company was also felt on the battlefield. To determine the effect of this requires a time and motion study, as well as a little geometry.

The system of analysis involved will be demonstrated solely for one manoeuvre using the pre-1808 battalion and a summarisation of the results for the principal manoeuvres for both the pre- and post-1808 battalions will be provided rather than prolonged analysis of all these manoeuvres.

The first point that must be addressed in this analysis of the impact on tactics is marching distance. The distances involved are directly determined by the formation the infantry has assumed. [8]

The French battalion established in 1791 was organised with one grenadier and eight fusilier companies. However, the grenadier companies were often stripped off and formed into converged grenadier battalions. These grenadier battalions were not considered and the battalion with

eight fusilier companies was used for all calculations for French infantry between 1800 and 1808. Similarly, for the post-1808 battalion a similar analysis was made, but as all battalion companies were generally present with the battalion on the battlefield the battalion manoeuvres

were analysed using the full six company organisation. [9]

The calculations used to determine manoeuvring times were made with the assumption that a facing manoeuvre, an "about face" or a "left/right" face takes only a couple of seconds and was not worth taking into consideration when performing calculations. In the case of Figure

I, a situation. The 1st Fusilier Peloton must move farther than any other peloton. They execute a 45 degree turn which requires them to travel 55 feet. Being at full distance 1st peloton travels 10 peloton intervals. The time is then determined by the peloton performing two wheels, at 55 feet each, and advancing 10 peloton intervals. The total distance is 810 feet. If they advance at 260 feet per minute it will take them 3.1 minutes to cover that distance.

Similar analysis and calculations of the principal evolutions performed by the French infantry leads to the results that are listed in Table I.

The major point to note is that the change in the internal organisation of the battalion that occurred on 18 February 1808 was not just an administrative reorganisation, but a change that produced some very decided improvements in the French military system. With the sole

exception of the conversion of a line to "colonne d'attaque," every manoeuvre was speeded up significantly. It is worth noting that the loss in speed in executing this one manoeuvre amounts to 0.2 minutes, or 12 seconds, which is not significant. The time saved by a single battalion manoeuvring is not, as a unique few seconds, necessarily significant, but over the course of a battle the improvement in the manoeuvrability of all of the units amounts to a significant time

savings and must have significantly contributed to the reputation of the tremendous manoeuvrability of the French as well as to their ability to so regularly defeat their enemies.

This decree was the act of an administrator and a soldier. It is probably the least acknowledged of his administrative marvels. He is known for establishing the Code Napol‚on, for establishing a civil service where promotions are based on merit and test scores, as well as many other administrative actions that stand as the models for many of today's institutions.

His administrative skills and judgment in issuing the Decree of 18 February 1808 certainly ranks amongst these, though it is not emulated today as are many of the others. It allowed him not only to rebuild and expand his army so he could pursue his campaigns from 1809 through 1812, but it allowed him improve the tactical flexibility of his army.

[1] After these changes, the regimental staff consisted of: 1 Colonel, 1 Major, 1 Chefs de bataillon per battalion, 8 Adjudants-majors, 1 Quartier-maitre tr‚sorier (Quartermaster Treasurer), 1 Chirurgien-major (Surgeon major), 1-3 Chirurgien aides-major (Surgeon aide-major) [one less than the number of battalions Chirurgien aides-major was assigned to each regiment], 1 Chirurgien sous-aides (Surgeon Under Aides), per battalion, 1 Vaguemestre (Baggage master), 1 Drum major, 1 Drum corporal, 1 Chef de musique, 7 Musicians, 1 Master tailor, 1 Master cobbler, 1 Master gaitermaker, and 1 Master armourer.

The organisation of the companies within the regiment was as follows:

1 Capitaine, 1 Lieutenant, 1 Sous-lieutenant, 1 Sergeant-major, 4

Sergeants, 1 Fourrier, 8 Corporals, 64 Grenadiers (grenadier company

only), 104 Fusiliers (fusilier company only), 2 Drummers. The grenadier

company had 83 and the fusilier company had 123.

The companies were uniformly organised with 140 men. They were distributed as follows: 1 Capitaine, 1 Lieutenant, 1 Sous-lieutenant, 1 Sergeant-major, 4 Sergeants, 1 Caporal-fourrier, 8 Corporals, 121 Soldiers, 2 Drummers, 140 Total.

If the regiment undergoing conversion had four battalions the organisation of the first four new battalions was effected. The new fifth battalion was organised with the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, and 4th Fusilier Companies of the 4th Battalion and the 5th, 6th, and 7th Fusilier Companies were

sent to other reorganising regiments, but the voltigeur and grenadier companies were retained with the parent regiment in excess of normal organisational strengths.

For the purposes of this study an interval of 22 inches was used. The 22 inch interval gives fusilier peloton at full strength had a length of about 70 feet. This is what was known as the "distance entiere" or the peloton's full interval.

The second factor is the infantry's velocity. Velocity consists of two factors, the length of the individual pace or step of the soldier and the number of paces per minute. The length of the French pace was strictly regulated as was the various cadences.

According to the Reglement and the Manual d'Infanterie (an official 1813 compilation of all changes made to the Reglement, but not an official replacement for the Reglement) the most commonly used pace was the "pas de deux pieds," or 26 inches. This pace was used for all calculations of French manoeuvres.

The Manual d'Infanterie and the Reglement de 1791 both clearly state that all manoeuvres were executed at the "pas de charge," 120 paces per minute. Using this cadence and the 26 inch pace the march rate or speed of manoeuvre was 260 feet per minute. The manoeuvres used to develop the conclusions of this review are based on the 260 feet per minute speed of advance.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

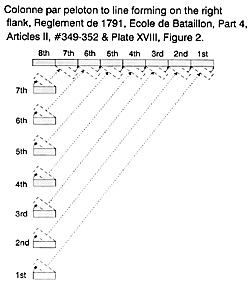

The first manoeuvre is the deployment from a "colonne par peloton" to a line forming to one flank. This is illustrated in Figure I (at right) and is the slowest method of deploying. This method of deployment was done by each peloton wheeling 45 degrees and advancing in line directly towards their final destination. Once there they performed another 45 degree turn and fell into line.

The first manoeuvre is the deployment from a "colonne par peloton" to a line forming to one flank. This is illustrated in Figure I (at right) and is the slowest method of deploying. This method of deployment was done by each peloton wheeling 45 degrees and advancing in line directly towards their final destination. Once there they performed another 45 degree turn and fell into line.

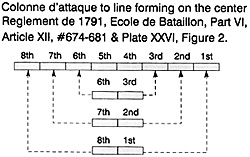

Figure II (at left) illustrates the fastest method of deploying, that of forming a line from the "colonne d'attaque." In all the following examples are at a full peloton interval, though the illustrations may not always clearly indicate it.

Figure II (at left) illustrates the fastest method of deploying, that of forming a line from the "colonne d'attaque." In all the following examples are at a full peloton interval, though the illustrations may not always clearly indicate it.