Battle of Jena

An Opinion

by Patrick E. Wilson, UK

| |

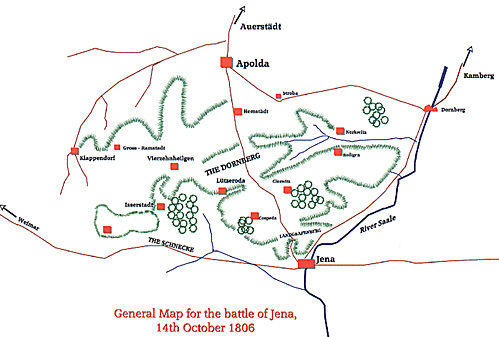

To Tauentzien’s right lay the greater part

of the Prusso-Saxon Army; namely the

Saxon’s of Zeschwitz’s 2nd division,

Grawert’s excellent 1st division and some

Grenadiers under von Prittwitz. Later that day

a detachment under Major-General von

Holtzendorff would move to the village of

Dornburg to cover the far-left flank of the Army.

The stage was thus set for the historic

battle of Jena and the future of Europe hung in

balance once again as two armies of formidable

reputation confronted each other for the first

time since 1795, when Prussia had withdrawn

from the first coalition deployed against a revolutionary

France.

The two armies which confronted

each other were very different and

represented their own epochs, one the heir of

Rossbach and Leuthen and seen as a rigid one

of fierce discipline but little recent experience.

The other, the victor of Ulm and Austerlitz and

known for its revolutionary methods of raging

war. Thus, the field of Jena as it would become

known, would see the clash of the old and the

new, as the heirs of Frederick the Great fought

it out with the forces of the new master of war,

Napoleon. Indeed Napoleon had been anxious

to avoid war with Prussia and had warned his

Marshals of its renown, telling Marshal Soult to

be wary of its Cavalry in particular.

War cam in a dispute over Hanover, when

Napoleon tried to return it back to Britain in

return for peace after he had given it to Prussia

only a year before for keeping out of the 1805

war. Prussia was not impressed to say the least

and abruptly declared war in the autumn of 1806.

Prussia possessed a large well trained

army, nearly a quarter of a million men and its

leaders, the Duke of Brunswick, Prince von

Hohenlohe-Ingelfingen, von Mollendorf von

Ruchel etc., all had fine reputations and a

wealth of experience. The only problem

seemed to be a general lack of decision when

it came to deciding upon a plan of campaign,

of which they had several.

This indecision led to the wasting of days and weeks, when a quick and decisive strike at

Napoleon’s forces in southern Germany may have caught them dispersed, a victory could

perhaps have bought armed support from Austria and undone Napoleon's successful 1805 campaign.

And yet, by the 13th October, despite a couple of unfortunate mishaps at Schliez and

Saalfield, the Prussian army would find itself in a very favourable position. Indeed, it has

been argued that the very indecision of the Prussian senior command had worked to their

advantage and they or rather Prince von Hohenlohe-Ingelfingen, would find himself with

an opportunity to inflict a severe defeat on one of Napoleon’s Marshals.

This was precisely what Hohenlohe was about to do when his chief of staff

Massenbach returned from Burnwick’s Headquarters on the 13th October 1806.

Massenbach brought with him instructions to remain on the defensive

whilst Brunswick with the main Prussian Army retreated for the Eble.

Thus, Hohenlohe’s orders were to cover the Saale River line and prevent

the enemy from interfering during Brunswick’s march to the Eble. He was there-fore

perfectly justified in his plan to attack and throw back into the Saale the French forces

currently occupying the Landgrafenburg and for this he argued vehemently, asserting

that it would be the right course to pursue.

But Massenbach, emphasised what he understood to be the purely defensive nature of

the orders they had received from Brunswick, the Prussian Commander-in-Chief,

which, argued Massenbach, precluded any form of tactical offensive. This of course,

was plainly not the case, for one cannot imagine a commander of Brunswick’s experience

issuing such rigid orders, strategic defence by no means excludes a tactical

offensive.

Hohenlohe though, sadly as it turned out for Prussia, gave in to

Massenbach’s arguments and thus missed out on a great opportunity, probably the best Prussia would have.

Across the valley however,

Lannes, the French commander on the

spot, did all he could to get his troops ready

to defend his position should the Prussians

attack and Napoleon, on receipt of Lannes’

report rushed all the troops he could to his

assistance. By 4pm Napoleon was there

himself and during this he had all of Lannes

5th Corps and his footguards under Marshal

Lefebure, placed upon Landgrafenburg. He

was also instrumental in getting Lannes

artillery in position.

What a contrast with Prussian activity

across the valley, Hohenlohe merely having

his men return to camp after his dispute with

Massenbach and the abandonment of his tactical

offensive. And yet, Hohenlohe still held

the advantage, for if he attacked first thing in

the morning he could still have had the pleasure

of tumbling both Lannes Corps and the

much vaulted “Grognards” into the Saale before

the arrival of their supports.

All Hohenlohe did was to lead Holtzendorff with his

detachment, as mentioned above, to Dornberg

to counter a perceived threat to his position

from that direction, a threat that at the time

had little foundation and only served to

weaken his main forces before Jena.

The 14th October 1806 dawned with a

heavy fog, which benefited General Tauentzien

as he positioned his limited forces of about

8,000 men in a dozen battalions, two cavalry

regiments and a couple of batteries in a defensive

line between the villages of Lutzeroda

and Closwitz. The heavy fog however disadvantaged

Lannes. Unable to see anything from

his front, he had to grope his way forward and

consequently collided with Tauentzien’s Prus-so-

Saxon division early on.

The subsequent fight rapidly developed into a soldiers battle,

with both sides taking heavy casualties and

their supporting artillery firing blindly into the

fog, killing both friend and foe. Gradually

though, Lannes divisions, under Suchet and

Gazan pushed Tauentzien’s division back towards

the Dornburg heights. Suchet successfully stormed Closwitz whilst Gazan took

Lutzeroda but upon reaching the heights of

Dornburg, they were vigorously counter-attacked

by Tauentzien’s hard fighting division

and Lannes was forced to commit his supports

to steady his front line.

But strangely enough Tauentzien did not press his advantage, instead

he halted, turned about and marched off

toward Klien-Romstradt.

What Happened?

For some time now Hohenlohe had been

listening to the roar of cannon from

Tauentzien’s battle with Lannes, as well as

receiving message after message describing

the severity of Lannes attack. He was also a

little annoyed to notice that General Grawert,

commander of his 1st division, was slowly

moving elements of his command towards the

sound of Tauentzien’s fight.

Finally comprehending the situation Ho-henlohe

reacted, ordering Tauentzien to retire

and reform near Klien-Romstradt. He then

sent Grawert’s cavalry

to cover this manoeuvre

and his infantry to occupy

and hold the Dornburg,

whilst directing Zeschwitz’s Saxon’s to

Isserstadt and the Schnecke pass to cover Grawert’s right.

Finally, Hohenlohe despatched an aide riding

flat out for Weimer with a request that General von Ruchel, who was

assembling his Corps there prior to following Brunswick on his way

to the Eble, to come to his immediate assistance with his 15,000 men.

Meanwhile the French had not been idle, Lannes troops recovered

from Tauentzien’s counter-attack and

made an assault on the key village of Vierzehnheilgen

which controlled the Dornburg

heights. The 40th Ligne under General of

Brigade Rielle actually entered the village

before the appearance of Grawert’s division

forced them to retire.

Further to the right Marshal

Soult made an appearance with his first

division (St.Hilaire). But his advance coincided

with another by General Holtzendorff,

who hearing the roar of Tauentzien’s battle

had decided to rejoin Hohenlohe’s main body.

Collinson with Soult’s advance was inevitable

and it occurred near the village of Rodigen,

northeast of Jena.

Holtzendorff attacking St. Hilaire’s division as it reached the ridge above

the village with his infantry but then realising

he was out-numbered he resolved to retire on

the nearby village of Nerkwitz. Utilising his

cavalry, Holtzendorff conducted a fine withdrawal

until Soult’s cavalry appeared on the

scene and attacked with such fury that not only

was Holtzendorff’s cavalry driven off but his

infantry was severely damaged too.

The French taking 400 prisoners, 2 colours and an

artillery battery that got stuck in a ravine in the

confusion and forcing Holtzendorff to retire

on Apolda and Stroba. Neither St. Hilaire nor

Soult’s cavalry followed this success up, for

Soult drew them off to the aid of Lannes, then

heavily engaged against Grawert’s division on the Dornberg.

To Lannes’ left another force was making

its appearance, this was Marshal Augereau’s

7th Corps and they attacked through the Isserstadt

wood, only to find themselves for the rest

of the battle involved in a grim struggle for the

village of Isserstadt with Zeschwitz’s Saxons.

However, a gap had developed between

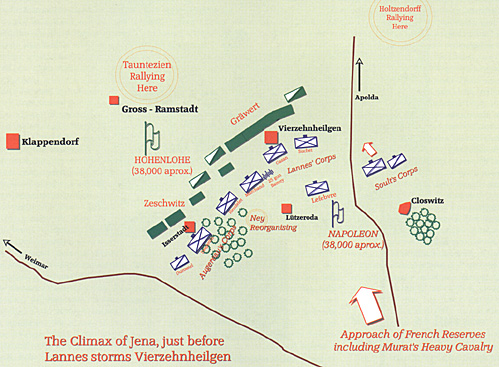

Augereau’s right and Lannes left, Napoleon

quickly covered this with a 25 gun battery but

it did not stop an impatient Marshal Ney, who

had been waiting for an opportunity to get into

action, from plunging into the gap at about the

same time that General Reille retired from

Vierzehnheilgen.

With his Corps cavalry and several elite battalions, about 4,000 men, Ney

charged with his natural impetuosity and

quickly over running a Prussian battery

pushed Grawert’s cavalry back and may have

entered Vierzehnheilgen too. But before him

stood over 20,000 Prussian and Saxon troops

with many guns that soon began inflicting loss

on his own meagre forces and the Prusso-Saxon

cavalry about 45 squadrons strong prepared

to punish him severely for his recklessness.

Luckily, Napoleon came to his aid;

sending his aide Bertrand to his assistance

with two of Lannes cavalry regiments as well

as having Augereau and Lannes move troops

to fill the gap between their Corps. Under the

cover of these measures Ney’s battered troops

were able to retire and regroup.

The state of the battle was now as follows:

On the French left Augereau held the Isserstadt

wood and Colonel Habert at the head of the

105th Ligne had just stormed the village of

Isserstadt. Between the Isserstadt wood and

Lannes left stood General Marchand’s division

of Ney’s Corps, which had replaced Ney’s

advance guard that had now retired. Lannes

Corps held the centre of the French position

with Lefebure’s guardsmen to the rear in support.

Lannes Corps was also battered and tired

from almost five hours of continuous combat

and was now taking casualties from the Prussian

artillery and Jager fire from in and around

the village of Vierzehnheilgen. On the French

right, Soult was arriving fresh from his victory

over Holtzendorff. In reserve, apart from

Lefebure’s guardsmen, the other divisions of

Ney’s and Soult’s Corps were approaching and

Marshal Murat, the Grand Duke of Berg, was

assembling his reserve cavalry.

Grawert’s division was also drawn up in a

classic Prussian formation; two battalion echelons,

fused on the right with the left leading and

looking as if they were on parade. It was a

splendid and awesome sight. To Grawert’s rear

left stood the rallied cavalry of Holtzendorff’s

command all that general had been able to send

to Hohenlohe’s assistance.

Finally in reserve there was Tauentzien’s division, currently reforming at Klien-Romstradt

and von Ruchel’s divisions marching up to Hohenlohe’s assistance and

expected soon.

From a Prussian view point everything was progressing well, the

initial French assault had been held, Grawert was poised and ready to

attack and everyone was now confident of a Prusso-Saxon victory.

It was about 11am and the climax of the battle had been reached,

Vierzehnheilgen was now in flames and Napoleon called on Lannes for

one more effort. The intrepid Lannes then led his divisions into a hail

of artillery shells and Jager bullets and surged into Vierzehnheilgen,

fighting raged in the streets as the French ejected its Jager defenders.

Hohenlohe sent Grawert’s men forward and Lannes victorious, though

exhausted divisions ran straight into them.

Contact was mutually unpleasant; Grawert’s massed volleys driving the French back to shelter

of Vierzehnheilgen’s ruined streets and environs, where they made the most of the cover it afforded.

Whilst the Prussians of Grawert’s division continued to fire regulation volleys

that had relatively little effect upon the French behind

Vierzehnheilgen’s walls and hedges.

The French inflicted severe casualties on Grawert’s men as they

stood before them on the Dornberg. Grawert would have been better advised

to storm Vierzehnheilgen, indeed several officers urged Hohenlohe to do so but he had decided

to call a halt and wait for Ruchel’s arrival.

This was a fatal mistake for he missed his best opportunity

of the day. He had stormed Vierzehnheilgen, and there is little doubt that Grawert’s division

could have done so, Lannes hard used and decimated divisions

may well have given way with dire consequences for the French centre,

considering the proximity of the Prusso-Saxon cavalry.

Instead, Grawert’s fine formations stood for two hours under heavy fore from

the French in and around the Smouldering ruins of Vierzehnheilgen, taking horrendous casualties

for no useful purpose and becoming increasingly dispirited. Though it

was not all one sided, for the French too took heavy casualties, especially from the numerous Prussian batteries,

having a number of guns dismounted and artillery caissons blown up.

At least once Lannes tried to break the Prussian line by attacking with his right but found himself thrown by a Saxon cavalry

charge that sent him tumbling back and almost broke his own line.

Hohenlohe was again urged to exploit this opportunity, this time by

Colonel Massenbach, who argued for a supreme effort with all the

available cavalry to buy time for Ruchel’s arrival and that to wait

passively may prove fatal. For once Massenbach was right. However,

Hohenlohe had just received some unpleasant news, Augereau’s cavalry

had driven off Zeschwitz’s Saxon cavalry and inflicted severe casualties upon his infantry.

At the same time Augereau’s infantry,

supported by Marchand’s division, had advanced and broken

Hohenlohe’s line and effectively cut off Zeschwitz’s Saxon’s from the

main body of Hohenlohe’s Army. This item of bad news had undoubtedly

convinced of the need to retreat rather than attack; a movement that

began well enough and would have succeeded had Napoleon not decided

to attack again at that precise moment.

It was now about 1pm and Napoleon was confident that he had

now enough reserves and that the Prussians and Saxons were worn

down enough to guarantee a successful general attack. Ordering Soult

to turn Hohenlohe’s left, Augereau to take care of Zeschwitz’s Saxons

and Lannes supported by Ney’s 1st division, to once more storm the

Prusso-Saxon centre. Murat’s reserve cavalry was to exploit any breakthrough.

And yet, elements of Hohenlohe’s forces still showed some fight, Tauentzien’s rallied division

intervening to save part of Grawert’s division from the sabre’s

of Murat’s cavalrymen. Whilst Zeschwitz’s Saxons turned upon

Augereau’s divisions and pushed them back into the Isserstadt woods.

Nevertheless Murat’s cavalry gathered in 2,500 prisoners, 16 guns and

8 colours and Hohenlohe’s once proud Prusso-Saxon Army was well and truly beaten.

It was at this unfortunate moment that Ruchel’s divisions made

their appearance upon the field of battle. Near Kapellendorf Ruchel

encountered Massenbach and was told of Hohenlohe’s lost battle.

Asking what he could do, Ruchel is told to advance through Kapellendorf to

Hohenlohe’s assistance. It was fatal advice. It would have better if he had taken up a defensive position to

cover the retreat of Hohenlohe’s forces, with perhaps Kapellendorf as his centre. Instead, Ruchel followed

Massenbach’s advice and advanced to Hohenlohe’s assistance. Meeting Hohenlohe, Ruchel gave him command

of his troops and together they formed the men into battle formation and marched off to meet the enemy.

It was unquestionably Hohenlohe’s final error of the day,

perhaps the worst. For he should have used these troops in a defensive

manner to gain time in which to rally his own troops, instead he sent

them off to attack the victorious French. Ruchel, undoubtedly a very

brave soldier, did not flinch and gathering in all available cavalry from

Hohenlohe’s forces he advanced. Encountering the French near Gross-Romstradt,

Ruchel’s cavalry made short work of Lannes and Soult’s

light cavalry and brought the French advance to an abrupt halt.

However, encountering the infantry of St. Hilaire’s division and Vedel’s

brigade, Ruchel halted his own infantry and began the regulation volley

fire that Grawert had used earlier in the day. The result very much the

same, the French artillery and skirmish fire decimated his formations,

though not without some loss themselves, and thoroughly disrupted

Ruchel’s alignments.

Like Grawert before him, Ruchel would have been better pressing home his attack with the bayonet rather than relying on massed volley

fire. St. Hilaire and Vedel seeing that Ruchel’s infantry were wavering, attacked themselves with the bayonet and despite all

Ruchel’s efforts, he received a serious wound near the heart but refused to leave his post, his gallant and somewhat fool-hardy

attack collapsed before the bayonets of St. Hilaire and Vedel, and the sabre’s of Murat’s cavalrymen.

Ruchel’s men contributed another 4,000 men to Murat’s haul of prisoners as they too fell from the field of Jena.

Meanwhile the Saxon’s fighting Augereau’s men still held

their ground and were still in the Kotschau

area at the time of Ruchel’s defeat. When

French Dragoons and Cuirassiers attacked

from the rear and compelled them to lay down

their arms, and thus three complete brigades

of perhaps 6,000 men surrendered to Murat,

who had led the French Dragoons in person. It

was a sad end to a fine military display by the

Saxon Army. Only their Cavalry escaped to

fight another day.

This final act also brought the battle of

Jena to an end. French losses were about 6,500

men, the greater part being in Lannes Corps,

and Prusso-Saxon losses were about 10,00

men killed and wounded, with another 15,000

men taken prisoner. It had been a monumental

disaster; another Kolin but it had promised

great success too.

Opportunities

The 13th and 14th October 1806 saw the Prusso-Saxon Army of Prince Hohenlohe-Ingelfingen

presented with two distinct opportunities

of inflicting a severe check to the French

Grande Armée.

The first of these occurring on the 13th when Marshal Lannes crossed the

Saale relatively unsupported with his Corps.

Hohenlohe should have annihilated him but

Massenbach, his chief of staff, dissuaded him,

emphasising the defensive orders he had just

received from the Commander-in-Chief, the

Duke of Brunswick.

This was folly of the highest order. For had Hohenlohe acted as his

instinct told him, he would have been obeying

his orders in the widest sense, which was to

protect the march of Brunswick’s main army,

and by defeating Lannes and driving him into

the Saale, then Hohenlohe would have been

doing just that, as well as giving the French

something to think about at the same time.

The second opportunity occurred on the

14th, between 10 and 11am, when Marshal

Lannes Corps collided with Grawert’s division

in and around Vierzehnheilgen. By this

time Lannes divisions were tired and had

taken many casualties during their fight with

Tauentzien’s division that morning, whist

Grawert’s men were relatively fresh, keen and

thirsting to avenge Prince Louis’ death at

Saalfeld, four days earlier.

And yet, Hohenlohe held Grawert’s men back and instead of

storming Vierzehnheilgen at bayonet point

relied on massed volleys to dislodge Lannes,

had he forgotten how Prussian infantry had

stormed Leuthen despite the fierce resistance

of its defenders. Surely victory beckoned, especially

as Grawert’s infantry had more than

45 squadrons of cavalry to support them.

Lannes must have given way to the impact of

such a force. Yet, Hohenlohe halted and despite

the entreaties of his staff, would not give

the order to attack and consequently lost the

initiative to the French. His excuse afterwards

was that he was awaiting Ruchel’s arrival. But

that officer only received his request at 9am

and could hardly be expected to arrive before

mid-afternoon considering the fact that he had

to assemble his men and march up from Weimer.

It was therefore essential to attack the

French with what was available before they

too brought up supports and Hohenlohe knew

these were on the way but chose to remain in

the open, exposed to enemy fire and wait

Ruchel’s arrival. A fatal, as it turned out, mistake.

Finally there is Hohenlohe’s use of

Ruchel’s force at the battle’s end. This is

almost incomprehensible. Committing your

last reserve to the offensive when everything

depended upon finding a bastion behind

which you could rally your defeated troops

was surely folly. Ruchel could have formed

this bastion around Kappellendorf and the

subsequent events of the campaign may

have been different.

The battle of Jena reminds me of

Napoleon’s remark on luck: “What is luck?

The ability to exploit accidents.”

And that: “A man has his day in

war as in other things.”

It is manifestly clear to me that Hohenlohe did

not possess the ability to exploit accidents

and certainly seemed to have had his day

and perhaps rivals Junot at Valuntino for

letting opportunities slip. Though the real

reason may be that Hohenlohe, like other

Prussian leaders, had been at peace since 1795

and consequently lacked recent experience of

warfare.

Chandler, David G., The Campaigns of Napoleon, (New York: Macmillan, 1966. Reprint London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1987).

|

on the 13th October 1806 Marshal

Jean Lannes began to occupy the

Heights of Landgrafenburg above

the Thuringian town of Jena, opposite him

between the villages of Luterode and Closwitz,

stood the Prussian General von Tauentzien

with the 3rd division of Prince von

Hohenlohe-Ingelfingen’s Prusso-Saxon Army.

on the 13th October 1806 Marshal

Jean Lannes began to occupy the

Heights of Landgrafenburg above

the Thuringian town of Jena, opposite him

between the villages of Luterode and Closwitz,

stood the Prussian General von Tauentzien

with the 3rd division of Prince von

Hohenlohe-Ingelfingen’s Prusso-Saxon Army.

From a well conceived withdrawal, river line by river line to

link up with their Russian allies by Colonel

von Scharnhorst to a “military promenade” as

proposed by Colonel Massenbach.

From a well conceived withdrawal, river line by river line to

link up with their Russian allies by Colonel

von Scharnhorst to a “military promenade” as

proposed by Colonel Massenbach.

On the Prusso-Saxon side of the field, opposite Augereau

stood Zeschwitz with three Saxon brigades,

supported by the Saxon cavalry to his left.

Opposite Marchand stood the Grenadiers of

Dyherrn’s brigade and the cavalry who had

opposed Ney’s attack. Next came Grawert’s

fine infantry division, who stood on the Dornberg

heights behind the village of Vierzehnheilgen

where they had just arrived. Indeed, it was

Grawert’s artillery and Jagers who were now

inflicting casualties on Lannes divisions.

On the Prusso-Saxon side of the field, opposite Augereau

stood Zeschwitz with three Saxon brigades,

supported by the Saxon cavalry to his left.

Opposite Marchand stood the Grenadiers of

Dyherrn’s brigade and the cavalry who had

opposed Ney’s attack. Next came Grawert’s

fine infantry division, who stood on the Dornberg

heights behind the village of Vierzehnheilgen

where they had just arrived. Indeed, it was

Grawert’s artillery and Jagers who were now

inflicting casualties on Lannes divisions.

A furious barrage announced the French attack and the Prussians

and Saxons fought back hard and for the first hour at least, though

steadily going back, they kept up a steady front in the face of repeated

French attack. But eventually men began to give way, throw down their

arms, abandon guns and surrender. It was then that Murat’s cavalrymen

struck, thundering forward they did what Hohenlohe had failed to do

earlier in the day and turned disorder into rout.

A furious barrage announced the French attack and the Prussians

and Saxons fought back hard and for the first hour at least, though

steadily going back, they kept up a steady front in the face of repeated

French attack. But eventually men began to give way, throw down their

arms, abandon guns and surrender. It was then that Murat’s cavalrymen

struck, thundering forward they did what Hohenlohe had failed to do

earlier in the day and turned disorder into rout.