Further Intelligence Reports

14 and 15 June 1815

by John Hussey, UK

| |

I offer them here because of their intrinsic value.

The first document is a letter from Major-General

van Reede, Netherlands military commissioner

at Wellington’s headquarters in

Brussels, [2]

addressed to Baron van Capellen,

the Netherlands Secretary of State for the

Belgic provinces, also based in Brussels.

It is three pages long, written in French in an elegant

and very legible hand. Enclosed with it is

a second document one-and-a-half pages long,

in legible French, unheaded and unsigned but

stated by van Reede as written by the Director

of Police in the Department of Jemappes.

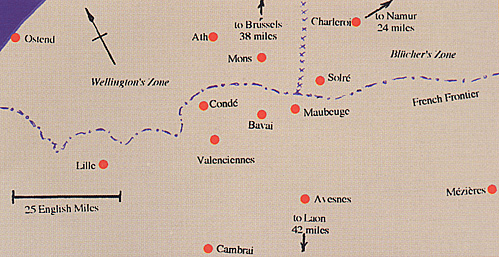

Jemappes itself is about 2 miles west of

the Netherlands fortified town of Mons and

thus some 12 miles west of Binche where

Wellington’s Anglo-Allied outposts touched

those of Blücher’s Prussians; in other words

the information is principally from that part of

France opposite Wellington’s sector, with the

French frontier town of Maubeuge some 12

miles due south and Valenciennes 17 miles to

the WSW of Jemappes.

Van Reede’s letter is only partially accented (and I have left this

unchanged) and very lightly punctuated,

mainly with commas: in certain places I have

replaced commas with semi-colons where the

sense of the phrases seemed to require it. The

translation into English is mine.

1. Major-General van Reede to Baron van Capellen

I have the honour to send Your Excellency

a report of the director of police of the Department

of Jemappes which agrees perfectly with

the reports received yesterday from General

Ziethen; it was not certain from those that Bonaparte

had arrived: however everything gave

rise to the belief that he was between Maubeuge

and Bavai [about 8 miles west of Maubeuge] or

in one of those localities. The troops from Valenciennes

[19 miles west of Maubeuge] have

moved to their right [eastwards] and joined

with those which had come [inserted above the

line: to Mézières - i.e. 50 miles SE of

Maubeuge] to the right of Maubeuge, which

was placed on their left, in order to concentrate

around that place; an artillery park of 40 pieces

of cannon had, it was said, come from Valenciennes.

From these movements one assumes the

possibility of an attack on Mons, and if the

news continues to indicate this it is probable

that the Duke’s army will assemble in the position

of Ath [12 miles NW of Mons].

However, up to the present there is no movement on our

side so far as I know[;] at least here there is no

order given for the departure of troops, so that

we appear [paraît-on] still nowise convinced

that Bonaparte can have serious schemes of

attack, in part because of the disadvantages of

his position even in the case of a success at one

point, in part because he would be seeking out

the army [i.e. his opponents’ army] in its full

strength, whereas in letting it enter France it

will diminish [in numbers] by the need to leave

in rear all which the masking [l’observation] of

[French] fortresses will indispensably require.

I was first informed yesterday, Monsieur le

Baron, that Prince Louis de Salm- Salm had

been arrested but without as yet receiving any

detail about what had been found chez lui; as

soon as I know anything I shall inform you of it. [3]

Yesterday during the day the Duke of

Cumberland [fifth son of King George III, and

currently the King’s deputy at Hanover] arrived

here and after passing several hours with

the Duke has continued his journey to England.

In the previous night [Dans la nuit

d’auparavant] there arrived an aide-de-camp

of Prince Schwartzenberg [supreme commander

of the Allied forces, currently in central

Germany], Count Paer, as well as the

Russian Lieutenant-General Baron de Toll. [4]

My despatch having reached this point I

had occasion to see the Duke of Wellington

who spoke to me in precisely these terms: I do

not believe that we shall be attacked[;] we are

too strong. I [van Reede] have learned moreover

that the dispositions are such that at need

in 6 to 8 hours his army can be concentrated

[and that] he intends to remain here in person

and generally wait until the French movements

are more evident before himself moving.

[Ma depeche en étant là j’ai eu occasion de

voir le Duc de Wellington qui m’a dit en autant

de termes: je ne crois pas qu’on nous attaquera

nous sommes trop fort. J’ai appris encore que

les dispositions étaient telles que dans 6 à 8

heures son armée peut au besoin être reuni il

compte rester ici de sa personne et attendre en

général que les mouvements des Français soyent

plus prononcés avant de se mouvoir.]

I have the honour to be, Monsieur le

Baron, 2. Report enclosed with the above letter

Mons, 14 June 1815

Information which I consider certain

states that the French arrived in force yesterday

at Merle-le-Château [Mérbes-le-Château,

8 miles ENE of Maubeuge], that there are

estimated to be at least 25,000 men between

this point on the Sambre and Solre-le-Château

towards Maubeuge.

The officers say that they are very numerous

and that they await Bonaparte’s arrival at

any moment for the start of hostilities. Napoleon

left Paris in the night of 11/12 June according

to the Gazette de France. They seem full of

ardour and the desire to penetrate into Belgium.

News from frontier points towards Valenciennes

say that the French advanced posts have

been withdrawn, even that there are few

[troops] at Valenciennes although 21 thousand

men were reviewed there three days ago.

All the French frontier communes are

overwhelmed with requisitions of all kinds.

The armed forces act like bailiff’s men and

furthermore have made numerous arrests of

the most important people to ensure the delivery

of the required contributions and produce.

Police supervision has become so very suspicious

that everyone is frightened and in general

the inhabitants of the communes pray for

the moment when they will be delivered from

all such agonies and excessive requisitions,

for it is said there are communes from which

more is demanded than they possess.

We should first of all remember that Napoleon

left Paris at 4 a.m. on 12 June and was

at Laon that night, reaching Avesnes on the 13th. His army moved east of Maubeuge and

crossed the border into Belgium not long after

dawn on Thursday, June 15, 1815, striking

against the Prussian army in front of Charleroi,

not at Wellington’s at Mons. The Allied

high command’s Intelligence had been slow

to detect this plan.

The fullest reports of Allied Intelligence

in the weeks leading up to the invasion are

found in Wellington Supplementary Despatches

vol x (1863), p.424 onwards, and may

be summarised as follows.

On 6 June reports said Napoleon was leaving Paris that day for

Douai (wrong), that artillery was gathering at

Laon and that Napoleon’s plan was to make a

feint against the Prussians and a real attack on

Wellington.

On the 7th reports (wrong) came of the Emperor going to Valenciennes

(opposite Wellington’s western sector), and

the next day that the Old Guard would go to

Maubeuge, the Young Guard and many line

regiments to Valenciennes (wrong).

On the 9th the Prussian Major-General von Müffling

reported that the main concentration area was

Valenciennes-Cambrai, but that the Young

Guard would go to suppress the royalist revolt

in La Vendée (wrong). That same day Gneisnau

believed that the French would withdraw

from the Belgian frontier southwards to a

Somme-Aisne position.

On 10 June Wellington had received a

report (wrong) that Napoleon had reached

Maubeuge (only 12 miles due south of Mons

in the Duke’s sector) and had gone west to

Lille (under 40 miles from the Duke’s supply

port of Ostend), while his outpost commander,

Dörnberg, thought (wrongly) that Napoleon

was already at Laon with 80,000 men.

On the 11th Dörnberg heard that Napoleon had

apparently been in Valenciennes for five days

and was now in Avesnes (both reports incorrect),

while the Duke now thought that the

Emperor had still been in Paris up to the 7th

(correct); however, Wellington remained concerned

over the defences of Mons, the Condé

canal and Tournai.

On 12 June Gneisnau at Namur declared

that any danger was ‘fast disappearing’, but

reports came in that day of a massive concentration

forming between Maubeuge and Mézières

-- a span of nearly 50 miles, however --

with the Emperor expected at Avesnes, i.e.

due south of Maubeuge (on the western

flank), while other information suggested that

the French would attack on the anniversary of

Marengo [14 June].

In sum, much (but not all) of the information suggested that if the French

really should attack and were not merely

bluffing, then the sector west of Mons and

Maubeuge was most at risk.

But the information sent to Brussels and

Namur on the 14th was both more precise and

more accurate and it indicated a considerable

French movement eastwards, with Maubeuge

perhaps being at the left flank (and not the

centre or right) of Napoleon’s host.

This did not affect Wellington’s views. Gneisnau only

began to think of concentrating his ‘widely

scattered’ forces at noon that day; towards

dusk he thought ‘in case of necessity’ a further

concentration might prove wise; around 10

p.m. he believed fighting might be imminent. [5]

To the evidence in WSD I would add three

further items highlighting Allied thinking: two

of 13 June and the other of the 14th.

The meeting of Blücher’s staff officer Colonel von Pfuel

with Wellington and Major-General von Müffling,

the Prussian commissioner in Brussels,

took place on the 13th and was concerned not

with defensive measures but with plans for the

Allied invasion routes into France: this meeting

is covered in detail by my article The Shadow

of Ligny. [6]

The second, a message from the

Prince of Orange concerning administrative

questions on 13 June, and the third, Orange’s

report of frontier activities on the 14th, both

appeared in the Journal of the Society for Army

Historical Research in 1999. [7]

We know that on the morning of 15 June

Müffling was still relying on the previous

day’s reports from the Prussian forward commander

Lieutenant-General von Ziethen, and

now we find van Reede similarly aware of

Ziethen’s 14 June reports, besides that of the

Jemappes police chief. [8]

The information from the police chief

about the sufferings of French civilians at the

hands of their own troops strongly suggests

that had Napoleon achieved the ‘liberation’ of

Belgium his new subjects would have faced

difficult times.

Save for van Reede’s letter it has not been

noticed, I believe, that Wellington was obliged

to give up several hours on Wednesday the

14th to discussions with HRH the Duke of

Cumberland. There had been a certain amount

of disagreement concerning pay and subsidies

for Hanoverian troops and this possibly could

have been among the topics raised, but even if

it was not it is plain that Wellington’s attention

was being distracted by many different inter-Allied

or royal protocol matters at this time.

It is interesting that General van Reede

should have concluded in Brussels on the

15th, from information just received, that if

French movements meant anything they could

indicate a possible attack on Mons in the

Anglo-Allied sector.

We know from the account

of Dörnberg that he himself on 14 June

had convinced General Clinton, commanding

at Ath, of the imminence of a French attack,

though Clinton added that Wellington did not

believe it. This disbelief is now independently

re-confirmed by van Reede. [9]

The Allies had variously estimated

Napoleon’s field army in the North as up to

120,000 men; [10] against this Blücher’s Prussians

numbered 130,000 and Wellington’s

heterogeneous Anglo-Allied force a further

90,000, excluding garrison troops.

This over-all inferiority of the French informs van

Reede’s estimate of the difficulties of

Napoleon’s ‘position even in the case of a

success at one point’. However, his words

show him preoccupied with the Anglo-Allied

sector Mons-Ath and hence his next phrase

about the danger for Napoleon in ‘seeking out

the army in its full strength’ implies, I think,

that the opposing army ‘in its full strength’

would outnumber the 120,000 French -- in

other words that the Anglo-Allied 90,000

would be joined with the Prussians to form a

united and preponderating force. [11]

It was only after writing most of his despatch

on 15 June that van Reede saw Wellington.

This is perhaps the most interesting part of

the letter for van Reede then learned that Wellington

still did not expect the Allies to be

attacked because of their overall strength, and

that the Duke estimated the concentration time

needed for his army at six to eight hours.

Wellington’s statement of his determination to

make no premature move, preferring to wait for

the French to disclose their hand unmistakably,

implies that he judged the risk of making a false

move greater than the disadvantage of consequent

loss of time.

In summary, General van Reede’s letter

gives a good deal of fresh and very interesting

information on the events of the 14th, the

prospects for the coming days as seen by a

senior Dutch officer, and the opinions of Wellington

on the eve of the campaign.

|

Thanks to the generosity of two good

friends in Belgium, Mr Philippe de

Callatay and Dr Jacques Logie, I

have seen two hitherto unpublished documents

bearing upon the opening of the Waterloo

campaign and unearthed by Dr Logie in

the Nationaal Archief at The Hague. [1]

Thanks to the generosity of two good

friends in Belgium, Mr Philippe de

Callatay and Dr Jacques Logie, I

have seen two hitherto unpublished documents

bearing upon the opening of the Waterloo

campaign and unearthed by Dr Logie in

the Nationaal Archief at The Hague. [1]