Another French Myth

“Artillery Innovator” Gribeauval

by Dave Hollins, UK

| |

Jean Baptiste Gribeauval – an able siege technician, but not deserving of his reputation. It does not, for example, actually take more than an hour’s research in the British Library in London to disprove this as far as Austria is concerned. Why do many authors not do this kind of work? To some extent, because it is outside their area of direct interest (France or UK usually) and they lack the linguistic skills – but the need to “read around the subject” was drummed into all of us at school! Other factors have also come into play. Since the Prussian Moltke developed modern army organisation in the late 19th century and the two World Wars happened in the 20th century, it has been fashionable for many authors, especially in the USA, UK and France to focus on French sources alone. As a result, where something is new to the French army, it is immediately taken to be an ingredient of Napoleonic success (over those Germanic peoples!) and thus new to the world. But was it? After all, skirmishing certainly wasn’t. Consider another tale – that of Jean-Baptiste Vaquette de Gribeauval (1715-89). Pick up most books on artillery and you will find that he is credited as the father of Napoleonic artillery and the engineer, who made key advances and modifications to the pieces themselves, turning them from the heavy pieces, which had lumbered around the mid-18th century battlefields, into efficient, mobile pieces, although there is a grudging acceptance that he was “influenced” by existing French, Austrian and Prussian designs. First, a word of warning: French guns were shipped to North America to aid the colonists in their 1776-81 rebellion against British rule. On the creation of the United States, its army formally adopted these guns and around 1800, both Toussard and a translator of de Scheel produced books in English as manuals for the US artillery (see below for de Scheel; Tousard, Louis de (1749-1817). American Artillerist's Companion; Or, Elements Of Artillery, Treating Of All Kinds Of Firearms In Detail, And Of The Formation, Object And Service Of The Flying Or Horse Artillery, Preceded By An Introductory Dissertation On Cannon. George Nafziger notes “A substantial portion of this work is taken from French manuals of the period”). Such being the way of tradition, it is North American authors in particular, who have pushed the tale of Gribeauval’s radical designs. However, in the course of researching Osprey New Vanguard 72 on the Austrian artillery of the Napoleonic period, it became quite clear that many of these so-called innovations were in fact in existence on the Austrian Lichtenstein system introduced in 1753.

Debates on the Internet and looking through recent works, such as Nafziger: Imperial Bayonets and Chatrand’s two Osprey New Vanguards on French artillery, failed to pin down the exact dates when Gribeauval had “invented” these new features. It was never disputed that Gribeauval had gone to Austria in 1758, but this was five years after Lichtenstein’s system had been introduced and the two nations had only become allies in 1756, after being on opposing sides in the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-48). So, when did Gribeauval devise these “innovations” and how did they get to Austria five years before Gribeauval arrived? What should we make of the man himself – was he actually the fabled engineer and gun designer? It took about two hours research on the Net and in Christopher Duffy’s book: Instrument of War (2000) to discover what follows. I began with a Germanic source now on the Net – Wurzbach: Biographisches Lexikon des Kaiserthums Osterreich (1856-91), a huge encyclopaedia, which in typically Germanic style (and in marked contrast to the above) includes foreign sources. The entry for Gribeauval is at www.literature.at/webinterface/library/ALO-BOOK_V01?objid=11809&page=334&zoom=3&ocr and for its main source, uses Gaucher de Passac: Precis sur Msr de Gribeauval (Paris 1816). There is other information drawn from the Net – one rather amusing US site claims that putting the rammer on one end of a pole and the sponge on the other was a sign of US innovation, so there is someone else who might consult the original drawings for the 1753 system (also shown in NV72 Plate D)! A French MinerJean Baptiste Vicomte de Griebauval was born in Amiens on 15th September 1715 and joined the Royal Army artillery as a volunteer in Paris in 1732. Within three years, he was commissioned into the La Fere Regiment as an artillery officer, devoting himself to the miners section. In 1748, Gribeauval had become involved in experimental work with the existing de Valliere siege guns (which had standard tubes, but a variety of carriages), apparently in relation to the design of a new siege gun carriage. However, no changes were actually implemented. Four years later, in 1752, he had advanced to captain in the Miners and commisaire d’artillerie at Heudon. His reputation as a skilled engineer was such that Minister of War Comte d’Argenson selected him to study the Prussian artillery, which was then enjoying the highest reputation in Europe. Gribeauval wrote a comprehensive re-port about the defences and their artillery on the Prussian borders and in its frontier fortresses. In the meantime, the Austrian artillery had undergone a comprehensive overhaul after the War of the Austrian Succession. The Director of Artillery, Prince Wenzel Lichtenstein, had overseen a complete new system designed by Andreas Feuerstein and a team listed in Duffy: Instrument p.271. The system itself standardised the carriages and lightened both them and the barrels to create a mobile field system, augmented by heavier siege and fortress guns. It was thus not the equipment side of the artillery, but a desire to improve the technical personnel, which prompted the Austrian Empress Maria Theresa to request the French King to transfer some able artillery and mining officers. At this time, Austrian Miners were a section of its artillery branch , but here is where the confusion seems to have begun. Today, we think of engineers as being involved in the design and maintenance of large pieces of equipment – a meaning, which has been grafted on to Gribeauval. However, in given his mining service, it is better to quote Chris Duffy, (Instrument p. 291) “The fundamental business of military engineers in the eighteen century was to build and attack fortresses”. In 1758, as a Lieutenant-Colonel in the Miner Corps, Jean Baptiste Gribeauval accompanied Comte de Broglie, the French general, to Vienna. Initially, he was appointed an Austrian Generalfeldwachtmeister (Major General) and instructed the Austrian artillerymen and their mining section in siege tactics – including the positioning of guns, mining and trenches. In this post, Gribeauval demonstrated his exceptional knowledge, commanding the Austrian artillery in the siege of Neisse in 1758 and improving the fortifications of Dresden in 1759. However, his main role in Austria is apparent from his next assignment: On 20th January 1760, Gribeauval and Prince Charles of Lorraine were tasked with reviewing the whole Austrian engineering service. His response two weeks later on 2nd February focused on the personnel, but also described the failures of Austrian sieges. Based on French organisation, he recommended in his formal proposals of 16th February that the Austrians establish a corps of sappers, (an idea he had considered in the previous year), as a separate unit to provide the manpower to dig guns in and prepare fortifications. Ordered to set up this unit, Gribeauval was soon leading his sappers with great success during late July 1760 in the siege of Glatz. In March 1762, Gribeauval wrote his famous report, which sought to compare French and Austrian artillery, to Paris – described by Duffy as “the beginning of the decisive pre-Napoleonic artillery reform in France”. He had only been directly involved with the heavier Austrian siege guns, but reviewed the whole Lichtenstein system, whose principles underlying the design applied as much to the field as siege guns. Soon after, he was appointed to serve under FML Guasco, the fortress commander of Schweidnitz (captured from the Prussians in Oct 1761), and on 6th August, they were under siege themselves by the returning Prussians. There, aided by Hauptmann (captain) Pabliczek, he directed the mining operations against their enemy counterparts. Frederick particularly mentioned Gribeauval and noted that the Prussians were unable to counter his deployment of explosive mines. Frederick complained that the “engineer Gribeauval is always preparing new tricks against us”. During this siege, Gribeauval also oversaw the testing of the Wall carriages for the defence guns, which he and the Austrian designers had been working on. The fortress fell on 9th October 1762, but only because a shell fell in the main magazine and ignited it. After initialling refusing to acknowledge Gribeauval, Frederick invited him to dine at his table regularly in a bid to draw him into Prussian service. When peace was made in 1763, Gribeauval initially went back to Vienna, where he was appointed a Feldmarschalleutnant by Empress Maria Theresa, but this did not prevent him from returning to France, where he was appointed a Lieutenant General in 1764. During the following year, 1764, new gun barrels were tested at Strasbourg amd demonstarated (as Lichtenstein had already done) that these shorter barrels were the equal of the former longer barrels (in France’s case, of the de Valliere guns). On 13th August 1765, Gribeauval issued his first decree – here there might be more confusion as the words ordinance (decree) and ordnance (artillery equipment) are easily confused. There then followed an extended dispute between the followers of the old de Valliere system (les rouges – the reds) and the supporters of the new designs (les bleus – the blues). Gribeauval was only in a position to consolidate his sweeping changes to French ordnance, when he was appointed Inspecteur Général de l'Artillerie in 1776 with the backing of the War Minister of the 1770s, Claude Louis de Saint-Germain. It was the decree of 3rd November 1776, which formally introduced his entire new artillery system, which also provided the guns shipped to the rebel colonists in North America. Gribeauval later fell into disgrace because of court intrigues, but shortly before his death in Paris on 9th May 1789, he was appointed Inspector General of the Grand Arsenal by Louis XVI. The Moral of the TaleSo, a few points come out of this. First Griebauval was actually an engineer only in sense of being a specialist miner within the French artillery. Secondly, he taught and directed siege tactics, not as is often claimed the whole Austrian artillery. Thirdly, his “collaboration” with the Austrians extends only to siege tactics and the testing of a new design of Wall Carriage. Contrary to popular myth, although he seems to have been involved in initial experiments with siege guns, there is no “new siege gun carriage design” of 1748 – when Gribeauval was a junior officer in the Miners. In order to consider Gribeauval and his part in artillery development, it is essential to go back to the primary material. Gribeauval’s part was set out comprehensively in “Tables de constructions des principaux attirails de l’artillerie, proposes et epouvees depuis 1764 jusqu’en 1789 par Msr de Gribeauval, executees et recueilles par Msr de Mauson, marechal dechamps, et par plusiers autres officiers du corps royal d’artillerie du France” (Paris 1792), a truly monumental work of 3 volumes with 125 plates. Its title alone reveals that the changes have happened “depuis 1764” (since 1764). Although Gribeauval was in overall charge from 1776, his position seems to be similar to that of Austrian artillery director, Prince Wenzel Lichtenstein. There is nothing wrong with using the head man’s name to describe the system, but it is not the same as saying Gribeauval was involved in designing the system as a great modernising engineer (In Austria this work was conducted mostly by Feuerstein and his team). The dates are also backed up by the often-quoted: Scheel, Heinrich Otto (1745-1808). A Treatise Of Artillery; Containing A New System, Or The Alterations Made In The French Artillery, Since 1765 / Translated from the French of M. de Scheel. Philadelphia, 1800, (also partially reprinted as De Scheel’s Treatise on artillery. Edited by Donald E. Graves 1984). Again, these alterations date from 1765, the original book being: Scheel, de. Memoires D'artillerie Contenant Les Changements Faits Dans l'Artillerie Francaise En 1765. Paris (1777). And what of the artillery systems themselves? That will be require a further article, but for time being, consider the many claims made for Gribeauval’s innovations - double movement/firing position for the heavier tubes, fixed/bound rounds tying the round and the powder charge together, the bricole (the short strap and rope used by crews to drag the guns), the systematic approach to the designs and their standardisation, the shorter barrels, the reduced windage (gap between the ball and the barrel bore), the lighter carriages created by paring the wood down and strapping the cheeks (or carriage walls), and the whole siege gun design - then look at NV72. Certainly, his 1776 decree introduced the prolonge (dragrope) and the metal axle, but when we consider that the supposedly new elevating mechanism already existed on the French 4pdr, it is not hard to see that Gribeauval is getting rather more credit than he deserves. Next time you come across any author claiming Gribeauval innovated much, check to see if the author has set out the siege technician’s real life story. Is there any reference to what can be simply obtained from the Net, the Lichtenstein system or consultation of the “primary material”- the “Tables de constructions”, Gribeauval’s 1762 report and the 1765/1776 decrees. If not – and especially where there has been a reliance on Toussard and de Scheel, plus recent North American authors like Chatrand, Graves and Adler – the moral of the tale is that you might well be reading yet more repetition of third-hand claims. AcknowledgementsI should like to acknowledge the very useful list of key French works placed on the Napoleon Series Forum (www.napoleonseries.org) by George Nafziger and Steven Smith: French Military Manuals and Instructions Concerning the Napoleonic Period, some of which are noted here. Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire # 79 Back to First Empire List of Issues Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List © Copyright 2004 by First Empire. This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com |

Many myths surround the Napoleonic

period and most have

evolved from the repeated copying

of secondary sources without checking

primary material. This has resulted in such

claims as none of the European armies using

skirmishing until a “reaction” to Napoleon’s

brilliance in about 1807 – the proponents of

such claims are not exactly sure of the date as

it relies on their not actually having read the

relevant German and Russian sources.

Many myths surround the Napoleonic

period and most have

evolved from the repeated copying

of secondary sources without checking

primary material. This has resulted in such

claims as none of the European armies using

skirmishing until a “reaction” to Napoleon’s

brilliance in about 1807 – the proponents of

such claims are not exactly sure of the date as

it relies on their not actually having read the

relevant German and Russian sources.

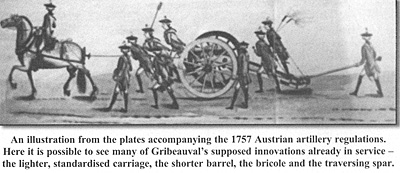

An illustration from the plates accompanying the 1757 Austrian artillery regulations.

Here it is possible to see many of Gribeauval’s supposed innovations already in service –

the lighter, standardised carriage, the shorter barrel, the bricole and the traversing spar.

An illustration from the plates accompanying the 1757 Austrian artillery regulations.

Here it is possible to see many of Gribeauval’s supposed innovations already in service –

the lighter, standardised carriage, the shorter barrel, the bricole and the traversing spar.