My Pilgrimage to St. Helena

Modern Day Visit

by Ben Weider, CM, Ph.D, Canada

| |

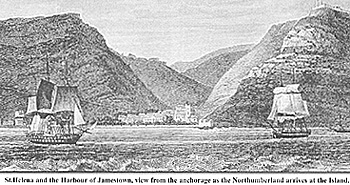

St. Helena and the Harbour of Jamestown, view from the anchorage as the Northumberland arrives at the Island.

I was frustrated about my inability to reserve passage to St. Helena, and by chance I met with the Vice President of a shipping line that travels between Southampton, in England, to Cape Town, in South Africa. Through him I was able to reserve four places onboard the freighter “The GoodHope Castle”.

I was seeking five places which would include my wife, my three sons and myself. It was to be a family pilgrimage. However, I was unable to reserve 5 places, because only 4 were available, therefore, my wife had to stay in Cape Town waiting for us to return after this historical trip to St. Helena.

I felt I needed to immerse myself in the atmosphere of the place where the Emperor lived his last days. I was following the example of the English officer, who holding his young son by the hand on the 6th of May 1821, in the death room of Longwood House said: “Look my son, this was the greatest man in the world”.

Finally, we flew to Cape Town and boarded the S.S. GoodHope Castle and we were on our way to St. Helena. This trip took four days. During the first two days, the seas were quite rough, and even the cows and horses that were onboard were seasick. The next two days were quite warm and sunny. Several hours before docking, I received a message from the radio room informing me that someone wanted to talk to me. For a moment, I thought my office was contacting me about a particular problem, but imagine my surprise when my friend and colleague, Mr. Gilbert Martineau, the Consul General of France on the island and a world-renowned Napoleonic historian, greeted me and informed me that I would be in St. Helena in a few hours and that he was waiting for me.

I then went up to the deck and together with my three sons, we looked out towards the horizon because we wanted to see the island as early as possible. Around midnight, I suddenly noticed a red light which was situated on the highest mountain peak of St. Helena, it was flush with the horizon. As I was staring at it, slowly but surely, I noticed the red light raising higher and higher above the horizon, and then I noticed a mass of land forming below it.

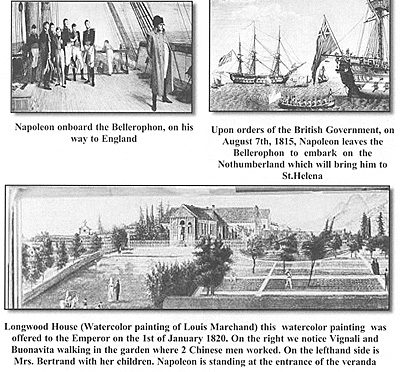

Napoleon onboard the Bellerophon, on his way to England Upon orders of the British Government, on August 7th, 1815, Napoleon leaves the Bellerophon to embark on the Nothumberland which will bring him to St. Helena.

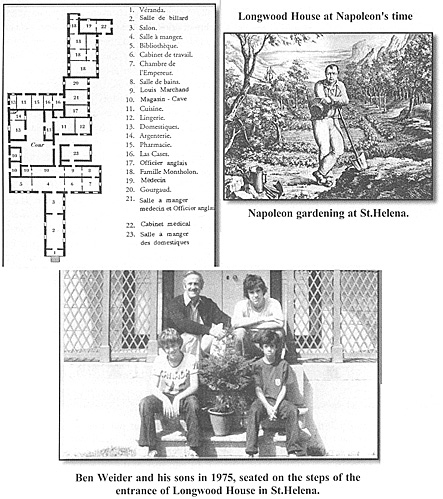

Longwood House (Watercolor painting of Louis Marchand) this watercolor painting was offered to the Emperor on the 1st of January 1820. On the right we notice Vignali and Buonavita walking in the garden where 2 Chinese men worked. On the lefthand side is Mrs. Bertrand with her children. Napoleon is standing at the entrance of the veranda.

While I was deep in these thoughts, a launch pulled up to the freighter, and I noticed it was my friend, Gilbert Martineau. He came on board, we shook hands, and he warmly welcomed me and my sons to St. Helena. After disembarking, we noticed there were about 150 people waiting. They were just curious to see who was arriving. The arrival of the boat, represented a major event in their lives.

The main street in Jamestown is called Napoleon Street and at the very beginning of the street there used to be a building called “Porteous House”, where the Emperor spent his first night on St. Helena. He hated the place because it had large windows and people were able to look right into his room. This house no longer exists.

Mr. Martineau drove us in his car to a home that he rented for us. We followed the road from Jamestown to Longwood House, which was approximately 6 miles. As we drove away from Jamestown, up into the mountains, it was interesting to see all the lights of Jamestown. The town is basically several streets and nothing else.

The home Mr. Martineau rented for us was situated near Longwood House where Napoleon lived out his exile. This home was very close to the home where the Countess and General Bertrand lived in after they left “Huts Gate” so they could be closer to Napoleon and could respond quickly whenever they were needed.

The next morning we met with Mr. Martineau and we went to visit Longwood House. Walking across the park to reach the residence evoked in us all great emotions. We entered through the rear apartments near by to where Mr. Martineau lived with his elderly mother.

Longwood House at Napoleon's time

Ben Weider and his sons in 1975, seated on the steps of the entrance of Longwood House in St. Helena.

Napoleon gardening at St. Helena.

As soon as we entered, we noticed the room that Baron Gourgaud lived in and nearby was the room where the Countess and Count de Montholon lived.

Right off this room, is where Dr. Barry O’Meara, and later Dr. Antomarchi ,stayed while attending to the Emperor. I have letters, in my collection that Dr. O’Meara wrote in this room. After looking through these apartments, Mr. Martineau took us outside and we went around to the front and he said, “Now, I will show you the different rooms that the Emperor used.” Our emotions were so intense that it was difficult to describe.

As we approached Longwood House from the front, I noticed that nothing had changed. The appearance of the house was exactly as it was in Napoleon’s day. Actually, I had read most of the autobiographies of the companions that shared the exile with Napoleon so I knew very well what happened in each room. Entering the main door, you come into the billiard room. This is where General Bertrand or the Count de Montholon received visitors, before presenting them to Napoleon. Here he dictated “The Campaign of Egypt” and numerous other works and maps spread out on the billard table. On the right are windows with shutters. A circular hole, which was about two inches in diameter, was cut in the shutters. These shutters were closed when Napoleon was in this room and he used to look out of this opening to see if British guards were around the home. If they were, he did not leave. In the same room is the original wooden circular map of the world. On the 6th of May 1821 the post-mortem was also carried out in this room by his personal surgeon, Dr. F. Antomarchi, and in the presence of several British doctors and various government representatives. Then, we went into the drawing room,

known as “Le Salon” where Napoleon, standing by the fireplace, his hat in his hand, would receive his official guests, often Count Las Cases acted as the interpreter. It was also in this room where Napoleon and the companions of the exile met before going into the dining room.

After dinner, they would again meet here to talk about events, play checkers and have an after-dinner drink. On the right, are two large sets of windows and it was between these windows where the Emperor died on the 5th of May 1821. A plaque was placed on the floor showing where his bed was.

Knowing the history of this house, I was able to visualize the many events that happened here. It was Consul General Martineau who worked diligently to restore everything in Longwood House and made sure its original character was maintained.

The room directly to the left was the ”dining room” where he often dictated. Here, after the autopsy, his body was laid out awaiting the funeral. In this room, the Abbé Vignali conducted his prayer while the companions looked on with great sadness. His Army bed was moved back into this room. Here the doctors, under the leadership of Antomarchi, made the famous death mask, and Napoleon’s body was placed into 4 coffins, one inside the other. At the extreme right of this room was Napoleon’s bathroom. It still contains the original copper bathtub where Napoleon took long baths in hot water. At times, even when the weather was nice and warm, Napoleon suffered from severe chills and therefore taking long baths would give him some relief. He would stay in his bath for hours. He often read while in the bath and sometimes dictated to one of the companions. Chills are one of the side effects of arsenical intoxication.

This original bathtub was taken to France and then returned to St. Helena in 1840, when some of the companions, headed by the Prince de Joinville, returned this bathtub back to its original place.

At the opposite side of the house, the very small room where Napoleon dictated his last Will is situated. This original Will is now in the French archives, but was kept in England at the Court of Canterbury until March 1853 when it was returned to France.

Visiting the dining room also evoked memories and deep emotions. I can visualize Napoleon sitting at this original dining table where he ate regularly with the Count and Countess de Montholon, Baron Gourgaud and Las Cases as well as Marshall Bertrand. Two valets, Ali and Noverraz served them. After the departure of Las Cases, Baron Gourgaud and the Countess de Montholon, and Napoleon often ate in his room or in the garden.

We then visited the gardens that were built around Longwood by Napoleon himself, as well as some of his companions in exile. It was in 1819 that Dr. Barry O’Meara urged and encouraged Napoleon to work in the newly proposed garden because he felt that Napoleon needed to exercise. The trenches of the garden still exist today, as well as the water basin. Napoleon told Count de La Cases “one day,

perhaps a hundred years from now, people will visit this area and admire our garden.”

He was off by some years, because over 150 years later, my sons and I visited the gardens as Napoleon predicted, and we did admire the work done there.

Visiting Longwood House and its various rooms left us emotionally exhausted. We returned to our home to discuss the day’s experience.

Two days later, we went through another emotional experience when we visited the Valley of the Tomb, better known as “Geranium Valley”. Napoleon died on the 5th of May 1821, the funeral services were conducted by the Abbé Vignali and held on the 9th of May. The English soldiers of the 20th Regiment, all 3,000 of them, lined the route as Napoleon’s funeral procession passed by.

At the Briars, Napoleon and the malayan slave Toby (October 1815). The Emperor became friendly with the elderly man and proposed to buy him back in order to give him back his freedom and to alow him to return home. This offer was refused by the Governor.

“The Ladder” of 699 steps is one of the features of St. Helena. It is immediately noticeable as one approaches Jamestown from the sea.

Longwood house has been restored and is now in the same condition as it was during Napoleon's day.

Nineteen years after Napoleon's death and entombment at St. Helena, his casket was opened to identify Napoleon before returning the body to France as the Emperor desired. Former exile companions were present, aged by nearly two decades, were astonished to see that the emperor's unembalmed body was almost perfectly preserved. Arsenic has checked the processes of decay in the triply enclosed and sealed coffin.

Ben Weider planting a tree at Napoleon's tomb. At left is the late Gilbert Martineau, Consul of France at St. Helena. Today, this tree is healthy and 10 meters high.

Twenty-four soldiers carried the coffin down the narrow path that led to Geranium Valley where his burial place was already pre-pared. Napoleon selected this place himself, as he found it peaceful. There was a brook whose water Napoleon enjoyed and every day, water from this brook was brought to Longwood House for his use.

A metal fence surrounded the burial area and a large cement slab covered most of the burial area. The companions wanted to inscribe “Napoleon” on the slab of cement but Sir Hudson Lowe, the British Governor, refused. He insisted that they inscribe “Bonaparte” instead.

Since they couldn’t agree, the slab of cement was left without a name for 19 years.

Mr. Gilbert Martineau gave my sons and me the pleasure and honor of planting a tree near the tomb. Today, it must be a huge tree. It was near this place that the Prince de Joinville, the son of Louis Philippe, with some of the companions of the exile, opened the tomb in order to identify the Emperor before the returning of the body to France.

Imagine their surprise when the tomb was opened to identify Napoleon, he was in a perfect state of preservation, Napoleon laid there as if he were asleep. They did not know, at the time, that the arsenic he was fed over the years caused the preservation of his body. Whereas, arsenic could kill, it could also preserve tissue. In 1854, at the time of the great friendship between Napoleon III and Queen Victoria, the land around Longwood House, and the tomb area was purchased by France for 7,100 English pounds and is now considered a Consulate so the area is protected politically.

The only time that Napoleon was happy on the island was during his stay at the Briars. This was the teahouse that belonged to the Balcombe family, and where Napoleon lived during the first two months he was on the island while Longwood House was being repaired and put into reasonable condition for Napoleon to use. Every effort was made to remove the hordes of huge rats that infested the grounds.

William Balcombe, a local businessman, offered to have Napoleon and his companions stay in the main house and suggested that he, his wife and his two daughters would move into the teahouse. Napoleon insisted that he did not want to displace them and thanked them for their generosity in allowing him to use the Briars. The teahouse today is exactly as it was during the time that Napoleon lived there. Dame Mabel Brooks, a direct descendant of the Balcombe family, donated the house and land around it to the French Government in 1959.

During his stay at the Briars, Napoleon became friendly with Balcombe’s youngest daughter. Young Betsy, aged fourteen, was a real tomboy who spoke some French. She constantly teased Napoleon and they soon became good friends. Through this friendship, her name became associated with Napoleon and she became a world-famous celebrity when she returned home to England. Years later, Napoleon III gave her a property of several dozens of acres in Algeria.

When Longwood House was ready to be occupied, Napoleon was getting ready to leave the Briars. Betsy cried uncontrollably and Napoleon tried to console her. He took out his personal hanky and wiped her eyes and told her to keep this hanky as a souvenir of their friendship. He then had Santini cut a lock of his hair and give it to her. This lock of hair was tested at the Harwell Nuclear Research Laboratory, and the result showed extremely high levels of arsenic.

William Balcombe always felt that Napoleon was poisoned and this story was handed down in his family to the present generation. Napoleon, during this period at the Brairs, was

feeling in good health and spirits.

I also received an invitation from the Governor of the island, Sir Tom Oates, to have dinner at Plantation House. This is the same house where Sir Hudson Lowe, the Governor of the island during Napoleon’s exile lived. I was able to visit the various rooms and office where Sir Hudson Lowe wrote his numerous dispatches about Napoleon to the British government. Driving around the island, I noticed a great contrast in scenery. In some areas it was like a desert, whereas other areas were green. Actually, nothing much is grown on the island, except flax.

While visiting the island, I was amazed to see a cemetery where numerous Zulus were buried. They were exiled to St. Helena after the war between the Zulus and England. The Zulu Chief is also buried there.

The population of St. Helena is now approximately 5,000 people and is made up of the descendants of slaves that were brought in from Madagascar and Malaysia. They are extremely friendly and warm.

Itwas on the 15th of October 1815 that Napoleon arrived on the Northumberland at St. Helena and it was on the 15th of December 1840 that his body was exhumed and returned to France.

|

In 1975, it was a very frustrating experience to obtain reservations to visit St. Helena. There is no airport, so I could not fly in, there are no passenger ships visiting St. Helena, so I could not reserve a place on such a ship, and helicopters cannot fly that far. The closest land to St. Helena is Angola, on the African coast. It is about 1,500 miles away.

In 1975, it was a very frustrating experience to obtain reservations to visit St. Helena. There is no airport, so I could not fly in, there are no passenger ships visiting St. Helena, so I could not reserve a place on such a ship, and helicopters cannot fly that far. The closest land to St. Helena is Angola, on the African coast. It is about 1,500 miles away.

I was very determined to go to St. Helena, because it would put me in the emotional mood to write my book entitled, The Murder of Napoleon.

I was very determined to go to St. Helena, because it would put me in the emotional mood to write my book entitled, The Murder of Napoleon.

We could eventually make out the lights of a small town, I knew immediately it was Jamestown, the only town on the island. Since St. Helena does not have docking facilities, we had to drop anchor off the island. When I first saw the island, a wave of sadness overcame me when I thought of what Napoleon must have felt when he saw the island for the first time and knew that he would spend the rest of his life here. He said to the grand Marshal Bertrand, “Better, we should have stayed in Egypt”.

We could eventually make out the lights of a small town, I knew immediately it was Jamestown, the only town on the island. Since St. Helena does not have docking facilities, we had to drop anchor off the island. When I first saw the island, a wave of sadness overcame me when I thought of what Napoleon must have felt when he saw the island for the first time and knew that he would spend the rest of his life here. He said to the grand Marshal Bertrand, “Better, we should have stayed in Egypt”.

Longwood House

Longwood House The Geranium Valley

The Geranium Valley