A Brief View of Waterloo

The Battlefield Itself,

Ligny, and Quatre Bras

by David Commerford, UK

| |

The Battlefield Itself

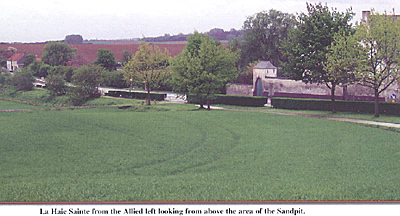

La Haie Sainte from the Allied left looking from above the area of the Sandpit. However, the general impression, for a Napoleonic nut at any rate, were of instant de ja view! This was accompanied by an equally instant impression of how the hell did they all fit in? It’s so small! Now granted my only other Napoleonic battlefield reference is the sprawl of Vitoria but having been in football crowds at the same size as either army present, it’s a wonder to me how the deployments worked. It’s also good reminder that battles of the period had frontlines far closer together than most wargamers imagine and that deep formations were a norm. I have to say that I greeted the news in FE71, that the Minister of Tourism for Wallonia has expansive plans for renovation around the Lion Mound. The premises could certainly do with smarting up. More worrying though is the state of La Haie Sainte where years of traffic on the main road are really starting to take a toll of the buildings fabric, its starting to look pretty tatty. Hougoumont on the other hand appears in fine fettle and I was duly impressed buy the bulk of the main buildings, the musket ball hits on the brick work and the length of the garden walls! Incidentally, my sole souvenir of the visit was the excellent little Paget & Saunders book on the above, from the Battleground series. In which I learnt the three large, dead trees on the Southeast side are in fact all that remains of the original wood, of which, I was unaware at the time. During our trek across the site one I was struck by the soil condition. I think the term is ‘loamy’. Granted that it has had many years of modern ploughing and fertilisers applied to it but assuming the basic structure has not changed too much, the famous mud conditions it produces are all too evident! Our main day on site followed some heavy showers the previous afternoon and in places it was really a goo. Round the edges of the ploughed areas, even where dry, the lightest foot pressure caused a 15 – 20mm imprint, it reminded me more of a beach than farmland.

Incidentally, I gather that there is a view that the postponement of the start of the battle had more to do with the strung out state of the French army and less to do with the condition of the ground. I think I may now have some sympathy for that. Waiting on the ground alone, given the prior amount of rain, would have been a total waste of time. It would have taken days not hours to effect a real change. One of my biggest impressions was not what you can see at Waterloo but rather what you can’t! Actually being on the ground was a perfect reminder of how limited the line of sight is. It raised again my estimation of those in Sibourne’s Letters who admitted that their personal knowledge of events was extremely limited. In fact, to a man on foot, the battlefield on the Allied side is really in two parts. The Brussels road marking a boundary. From the Hougoumont side, even ignoring the effect of that ‘lump’ La Haie Sainte is greatly reduced and Picton’s position invisible. Conversely, if you had been General Pack for example, Hougoumont itself might well have been in another country! Apart from the fact that it was his style anyway, it was easy to see why Wellington was on the move along the ridgeline, all day. It really was the only effective way of seeing what was happening. Bits of remembered reading popped into our heads all over the field. At the marker for Mercer’s battery we were minded of the remarks about his seeing just the tops of the Grenadiers a Cheval’s headgear before they came in view and looking at how the ground dropped away in front of the position, it was easy to envisage it. The story of the French mounted skirmisher who took pot-shots at Mercer with his carbine was also easy to credit, as the chap could easily have taken a ‘hull down’ position parallel to the battery and popped away with only his head and shoulders exposed. On a broader level, especially given the reduced height of the current ridgeline, its easy to see from the tactical area where Ney probably made his fateful decision to unleash the cavalry charges, he was effectively blind. Even further back, from the Imperial command post, those concerned could really have had no idea of what they were doing in relation to the reverse slope. One interesting thought occurred to me. What way was the wind blowing (if at all)? I’m sure that people have worked this out years ago from written evidence, if not direct attribution but I’m afraid I don’t know. It is relevant to Ney’s actions (not to mention the rest of the battle) as if it was blowing to the Allies, or there was little dispersing of the smoke that day, it makes his attack even more questionable. My postulation during the visit was that if there were any wind that day it would likely be blowing towards, or on a diagonal across the Allied line. This is on no more scientific basis than I recalled that RFC pilots in The Great War were always cursing the fact that the prevailing winds in Belgium blew them towards German lines. So German planes with a dead engine were blown home where as they found gliding back a major problem. Perhaps it just seemed that way! Any of you reading this who has the answer somewhere could you write into First Empire and let me know! Another ‘spotting’ concerned the French Grand Battery’s ridge. My immediate thought was “Christ that’s close!” another example of the unreality of wargamers regarding the nature of battle being instantly challenged! I believe that the actual distance to the Allied line varies between 400 – 700 meters. Whatever it is, being in front of it must have been an interesting experience! It is not hard to see just how much the reverse position favoured casualty reduction, or how much being on the front slope would have hurt! I have to say that somehow the battlefield from the French side is not as quite as interesting (maybe I’m biased). Although as I’ve previously hinted it certainly shows up as much, if not more, how difficult it was to control a period battle, even one on as small a frontage as Waterloo. Again it is evident how the battlefield rolls across and away from you and indeed how hard it is to see both ends of the line from the centre. However, on that side you do get to see Plancenoit and quickly you realise how deep in the ‘doo doo’ Napoleon was once an attack here moved from a threat to a reality. The village is well worth the visit and even if the layout is not quite the same as 1815 the church and the graveyard are an imposing position. If you travel the lanes and tracks east of the village, tracing the line of Bulow’s advance, it’s easy to see from across the fields how the Prussians had to use the church tower as a navigation point. Then indeed how difficult it was for Napoleon to accurately determine their movements in the first place. Ligny and Quatre BrasI must confess that these two were a bit of a side-show as far as we were concerned. There’s never enough time! What did impress me though was how different the terrain for both of them was in relation to Waterloo, the rolling effect is still there but at Quatre Bras its on a much larger, gentler, scale. Ligny is more broken and for the amateur a lot harder to trace mentally, dotted as it is with the various villages and modern expansion. Though we did our best and at least came away with impressions of what might have been, all those years ago. One of the more comic moments of the trip came at Ligny while tracing the course of Ligny Brook. Yours truly noticed a small sign in commemoration of a mill that stood there at the time. Instantly remembering the connection between a mill and the battle I thought “Fine we must be in the right area” then I thought “That’s funny, what an odd place to have a Moulin, right in the village.” Than it dawned on me as I reread the sign and saw the word ‘eau’ it was a bloody water mill! I was thinking of the windmill at Brye, where Wellington and Blucher met before the battle! Doh! It would not have been so bad if I were not standing on the little bridge across the brook at the time! One point, before passing swiftly on. It would not be the worse thing in the world if Monsieur Kubla, when contemplating spending his millions of Euros enhancing Waterloo, could divert a few thousand to some more signage, or view points, to both these battles. It seems a pity that we commemorate all those brave men at one of the famous triumvirate but don’t seem to pay much attention to those that fought and died at the other two. The Return LegTrying to keep in the sprit of the thing (all be it backwards) on leaving Waterloo we travelled down the main road to Charleroi (twined with Pittsburgh, USA and looking as about as attractive) with its mining and heavy industry before swinging speedily across to Namur. I had heard good things of Namur and given its associations with the campaign, was keen to make it our stop over. I was not disappointed. I would recommend this charming place to anyone who has a chance to visit. Particularly the castle area, that stands on a rocky eminence, high above the town. The walk to the top of the fortifications is a good old slog but the views across the town and along the river are wonderful, serving as an immediate reminder of the town’s strategic importance over the centuries. The following day we returned to ‘do’ Brussels! Again for anyone who’s never been, a charming place and of course you get to see Wellington’s HQ along with all the other sites. Oh! Those chocolate shops! Finally, in this advert for the Belgium Tourist Board I would like to mention the people of Belgium who were universally friendly and managed to speak three languages to my one and a bit! I now understand even better why some South African friends of mine found to their amazement that they could understand Flemish! Pity I have no Afrikaans it might have been better than my French! Visiting the Waterloo Battlefield Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire # 72 Back to First Empire List of Issues Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List © Copyright 2003 by First Empire. This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com |

Well apart from ‘The Monolith’ and Frichermont Convent being plonked at the left hand end of the British line, the feeling of ‘being there’ for me was pretty high. I did regret not having Adkin’s Waterloo Companion with me, if only for its photographs, with the accompanying text that points out the changes in where woods have come and gone since 1815.

Well apart from ‘The Monolith’ and Frichermont Convent being plonked at the left hand end of the British line, the feeling of ‘being there’ for me was pretty high. I did regret not having Adkin’s Waterloo Companion with me, if only for its photographs, with the accompanying text that points out the changes in where woods have come and gone since 1815.  One can only imagine what it must have been like for troops moving over it on ‘the day’ its easy to believe the stories of French soldiers losing their footwear from the suction of the mud. One thing that does seem to counteract this effect is crops. Losing my footing at one point, while trying to avoid the edge of the growing area, I stumbled into the field itself and found the footing a lot firmer.

However, I’m sure that this advantage would be outweighed by having to move through the height of the crop itself. Needless to say, wishing to keep on the right side of the local farmers I did not test that particular theory!

One can only imagine what it must have been like for troops moving over it on ‘the day’ its easy to believe the stories of French soldiers losing their footwear from the suction of the mud. One thing that does seem to counteract this effect is crops. Losing my footing at one point, while trying to avoid the edge of the growing area, I stumbled into the field itself and found the footing a lot firmer.

However, I’m sure that this advantage would be outweighed by having to move through the height of the crop itself. Needless to say, wishing to keep on the right side of the local farmers I did not test that particular theory!