Rosslau 1813

Sweden's Forgotten Battle

by Uwe Wild, Germany

| |

Reading through German-language books on the history of the Wars of Liberation, it is soon clear that there is particular criticism of the leadership of the Army of the North under Carl Johann. He was attempting to keep his army out of any major clashes and the reasons for this are often debated and I am certainly not going to discuss them in detail Despite all Carl Johann’s caution, Swedish troops were often in action during the 1813 campaign.

Starting at the Battle of Grossbeeren, then Dennewitz and Leipzig, not forgetting the action at Bornhöved, some clashes and a few sieges. Nevertheless, only individual Swedish units, usually artillery or Hussars, were engaged in these actions. However, it was different at Roßlau, where more than a complete Swedish brigade was deployed in fighting the French. After the battle of Dennewitz, the three French Army Corps under Marshal Ney [2] (4th, 7th and 12th Corps) withdrew to the left bank of the Elbe to reorganise. Ney reported to Napoleon, that he was

taking up a position between the Elbe and Mulde rivers, and there await re-inforcements, as with his current force, he was unable to take on the far stronger Army of the North.

On 10th September, he received the order from the Emperor to concentrate around Torgau and as a result, he withdrew closer to the Elbe. Ney was worried that the Allies had already crossed the Elbe as rumours were already circulating of a Prussian crossing at Coswig. In fact, only some raiding parties, mainly Cossacks, had actually crossed the Elbe, although they were now threatening French lines of communication.

The Marshal now had the full situation described to him by Napoleon and at the same time, received the order to hold his force ready, as the Emperor was planning an offensive against the Army of the North. Ney repeated his request for reinforcements, but aside from some random marches, nothing was else was done. During this time, Ney’s force was reorganised. The 12th Corps was disbanded, the troops distributed amongst the two other Corps. The Bavarian units were marched off towards Dresden to reinforce the main army.

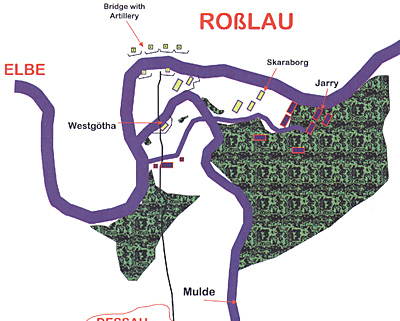

On the 19th, 500 Men [3] followed up behind them to take over guarding the Wittenberg bridgehead. Under this protection, the construction of a bridge and bridgehead defences at Roßlau began on the 17th. Responsibility for obtaining the boats required for this was given to the Swedish officer, Ingenieur-General Franc Sparre. A unit of Pontooniers detached by the Swedish Navy built the boat bridge from requisitioned boats and barges. As far as the bridgehead defences were concerned, the Swedes were able to utilise the old fortifications from the Thirty Years War. They were certainly dilapidated and much of the building material required was appropriated from local inhabitants, but the troops were still able to construct a substantial fortification there, which

was well suited for defence.

On 21st September, Ney received the following order from Napoleon: “You are to garrison Dessau immediately with a large force in order to maintain a good watch over the riverside. The most effective means of preventing an enemy crossing of the Elbe at Dessau is by concentrating the army at Wittenberg.” Above all, the Wittenberg fortress was an important point in the French line. On 22nd September, the Cossack Brigade under Prendel and Staal [4] crossed the Elbe at Roßlau and then advanced along both banks of the Mulde, where 1. Bug Regiment encountered the French cavalry under Dombrowski and Defrance. [5]

At the same time, an enlarged bridgehead was being constructed on both sides of the Mulde, part of the fortifications were on the road from Roßlau to Dessau where it ran along the Mulde riverbank and a second part lay further east between the Mulde and Elbe. [7]

Carl Johann’s orders were (as ever) to fall back on this bridgehead if the force came under attack. During the night of 22nd/23rd September, Ney received another order from Napoleon to launch attacks against the bridgehead to delay the crossing by the Army of the North and thereby, their advance on Leipzig. However, in doing so, he was not to become cut off from Wittenberg. It was intended that the 3rd Corps would move up to reinforce Ney. On the 24th, there was an engagement at Wartenburg, which put Ney into a state of agitation and prompted him to send his troops on unnecessary marches.

The result was that 4th Corps remained in position at Wartenburg, waiting to repel a crossing of the Elbe, when it happened, (it actually took place a week later). 7th Corps under General Reynier

[8] as moved back to Dessau again. On the 26th, Reynier marched off in three columns for Dessau. The lead units of the centre column, (13th Division under Guilleminot and Fournier’s cavalry

[9] ), ran into Staals’ Cossack brigade Staal, which after being reinforced with three battalions and 200 Chasseurs a Cheval, and fierce fighting, the French drove back on a Swedish unit.

[10]

After a brief clash with the Swedes in thickly wooded terrain, the French withdrew. The Cossacks lost 30-40 men, the Swedes 5 dead and about 40 wounded. A four-man Swedish Hussar patrol was sent forward by Colonel Ritterstolpe, to establish how strong the French force was. The Hussars were however spotted by the French outposts and with the exception of its officer, captured or shot.

Consequently, from the 25th September, Swedish troops were in the front line for the first time, where there was always a possibility of them being engaged in heavy fighting. It is easy to imagine Carl Johann’s annoyance. His worries were also raised, when on the 26th. Three shots were fired by the Swedish signal battery, followed by the Alarm being sounded on Swedish Jäger horns. They were signalling that a large French force was marching into the nearby Oranienbaum. Jäger companies were immediately despatched in support of the observation posts.

On the bank of the Mulde along the road to Dessau was a battalion from the Life Guard Grenadiers on outpost duty, who came under attack from a French unit. Just at that moment, the Jäger arrived in support and the French broke off the exchange. The Grenadiers had lost one dead. It couldn’t be called an action, as it only involved a small French reconnaissance force exchanging a few shots with the French. Nevertheless, the Swedes were hailed by the inhabitants of Jonitz (then a small village of 500 people, but now a suburb of Dessau) as their saviors. It didn’t matter much as the next day, the Swedes withdrew and left the village to be retaken by the advancing French.

When a French patrol began to advance cautiously towards Dessau on 27th September, the Swedes evacuated the south bank of the Elbe. Before the enemy appeared, Schulzenheim’s brigade withdrew behind the Elbe, so that even a few Grenadiers began to make mocking comments. Around 1400, the outposts also evacuated the town. It was still another hour before the French arrived on the Mulde, without having sent many troops ahead into Dessau. Two Voltigeur companies later occupied several houses in Dessau close to the bridge. As darkness fell, a troop of Cossacks slipped into Dessau and remained there overnight. When Carl Johann later learned that Cossacks had spent the night in Dessau, he was surprised. He had assumed that the French were not intending to hold on to Dessau and were more likely to be making a right turn to head for Wartenburg, to attack Bülow’s Korps. For this reason, he issued the order, “Once it is certain that Dessau is really clear of the enemy, then Colonel Björnstjerna will take a detachment back in there”.

During the morning of 28th September, the two voltigeur companies in Dessau engaged in an exchange of fire with the Cossacks and quickly gained the upper hand, pushing the Russians back. Then the Swedes pushed forward up a battalion from the Elfsborg Regiment, together with 50 Mörner Hussars and the Cossacks and advanced into Dessau. The voltigeurs were driven back and the action turned

into a stationary firefight, until half an hour later, a battalion from Gruyer brigade advanced and by outflanking the Swedes, drove them out of the town. The French immediately set about fortifying the town for defence. The Swedes lost 5 men dead and 24 wounded in the street fighting.

The other battalions from Gruyer’s brigade marched in at midday to reinforce the garrison. By this time, the Swedes were ready to launch a further attack on the town. Colonel Björnstjerna moved up with the battalions of infantry [12] , a squadron of Mörner Hussars and two guns from the Wendes Artillery Regiment. The guns fired on the town from a distance of 1 km, while the Jäger attacked and drove the French from various small gardens and an old brickworks outside the town. Then they tried to enter the town through the north gate, attempting to break it open with crowbars and axe. However, seeing the failure of the efforts to break in, Colonel Björnstjerna gave the order for a withdrawal on the bridgehead. The Swedes had already pulled back 50m from the walls, when the gates were opened by the French, who then directed canister fire from three guns on the retreating Swedes.

At that, Colonel Björnstjerna ordered a renewed attack on the gate, which prompted the advancing French to withdraw and their attack was stopped. The Elfsborg Regimental history describes

the action more dramatically:

It was now 1500. The Swedes had lost two officers [13] and 72 men, mainly from the Elfsborg and Queen’s (Drottningens Lifregimente) Regiments. Colonel Björnstjerna had three horses shot out from

under him.

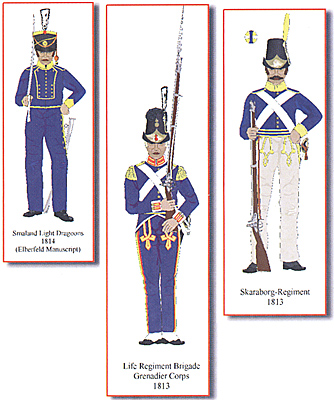

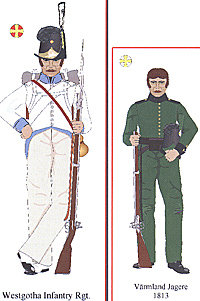

An hour later, several of Gruyer’s battalions and some cavalry moved forward in an aggressive reconnaissance towards the Mulde. There they engaged a battalion of the Swedish Westgöta battalion on outpost duty under Colonel Adlercreutz. The Swedes held their positions on the southern arm of the Mulde, then launched a counterattack over the bridge and drove the French back into the town. Later that evening, a patrol of four Smaland Dragoons was sent forward on reconnaissance - three were wounded in an exchange of fire with French infantry. After making his own reconnaissance ride to observe the situation around the bridgehead that evening, Ney realised that it was too strongly fortified in front, so he decided on a flank assault on the left side of the Swedish position for the 29th.

In the meantime, the Swedes had completed their works on the bridgehead – the earthwork on the road to Dessau on the north arm of the Mulde and a roughly 700m long fortification facing east between the Mulde and the Elbe [14], which closed off the protruding ground between the two rivers, now secured the position against French attack. As the north bank of the Elbe was higher, the Swedish

guns positioned there could dominate the whole peninsula. The bridgehead garrison was comprised of the 4. Brigade [15], together with the Westgöta Regiment from 3. Brigade.

To the east, about 2 1/2 km ahead of the defences, 142 men from the Elfsborg Regiment were positioned, together with the combined Jäger companies (about 270 men), plus 52 Light Dragoons from the Smaland Regiment. On the road to Dessau to the south, a battalion from the Westgöta Regiment held the outposts. The rest of the Swedish Korps was positioned on the north bank of the Elbe at Roßlau. Behind the ditches on the north bank were two Russian batteries together with the twenty guns of the Reserve Battery of the Wendes Artillery Regiment. Batteries from the Svea Artillery Regiment were moved up to both sides of the newly constructed boat bridge, downstream of the ditches.

Around 5.30 a.m., the Swedish outposts which had been sent forward for reconnaissance, encountered the advancing French, who were moving towards the bridgehead with three battalions. Following a lengthy opening bombardment by artillery, around 7.30 a.m., Gruyer’s brigade, supported by 2e Hussars, engaged the Swedish outposts east if the bridgehead. These units put up lengthy resistance until they were pushed back behind the fortifications. In the meantime, the Swedish artillery on the bridgehead and even the bridge over the Elbe had opened up, but the gunners then came under fire from French skirmishers. The French units, which had until this point mostly taken cover amongst the trees, now came out into the open ground and moved against the bridgehead. Contrary to the Crown Prince’s orders, to keep out of any significant fighting, General Sandels ordered an attack. A battalion from the Skaraborg [16] regiment together with the Jäger detachment advanced from the bridgehead and formed a line in front of it.

A ferocious exchange of fire broke out, during which the French fell back on a piece of woodland about 1.5 km east of the bridgehead. It was a frightening experience for the Swedish soldiers standing without cover in open ground, to see their comrades fall around them. The exchange of musketry was so ferocious that some Swedes could not grip their muskets, because of the metal parts becoming heated,

and the ammunition ran out. A second battalion of the Skaraborg Regiment was ordered to support them and it extended the first battalion’s line. Supported by the third Skaraborg battalion, the two Swedish battalions now advanced to avoid being unnecessarily exposed to enemy fire and drove the French far back into the wood. There the two sides engaged in hand-to-hand combats with bayonets.

One man from the Skaraborg Regiment tells a story that on he morning of the action, he was still busy with cutting new wooden soles for his shoes. As the ‘Alarm’ was beaten by the drummers, he pushed his half-finished soles up his shirt – they would subsequently save his life: During the fighting in the woodland, a voltigeur fell on him and tried to shove his bayonet into the Swede’s chest, but it became stuck in the wooden pieces. He fell back and was immediately tugged forward again as the Frenchman tried to remove his bayonet. The Swede now grabbed the musket barrel and the two of them

struggled over the weapon in the wood until the voltigeur was cut down by one of the Swede’s comrades. Now however, French resistance stiffened; they formed a line and went over to the counterattack, driving the Swedes from the wood.

At the same time, French artillery moved along the southern bank of the Mulde to a position facing the Swedish infantry and fired across the river, straight into the flank of these retreating units. In the meantime, Sandels had moved up a battalion from the Elfsborg Regiment. However, the Swedes were taking heavy casualties from the artillery fire

[17] and had to pull back to the fortifications under cover from their own artillery. The firing continued for several more hours and only faded away around 1300.

The lengthy resistance of the weak Swedish force, which had mainly fought in open flat ground against French troops partly protected by the woods along the edge of the Mulde can only be explained by the support they received from their own artillery posi-tioned on the north bank of the river. The Swedish losses ran to 15 officers

[18] and 277 men; French losses cannot have been more than about half that number.

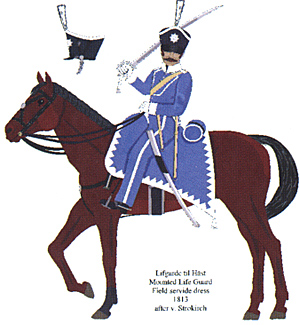

[19] The grave of Lt. Celsing of the Swedish Life Guard Cavalry in the Zerbst cemetery is worthy of note. This officer died of his wounds on 8th October 1813. Various officers and men from the Life Guards escorted the General Staff and were also employed as messengers. Presumably, he was wounded at Roßlau.

In the face of events, Ney shied away from an attack on the fortified bridgehead and put it under a standard siege. To defend against Swedish artillery fire, small earthworks and trenches were constructed. He had planned to work forward slowly towards the bridgehead (which is how events turned out), and later, construct a boat bridge over the Mulde beyond the range of Swedish guns, so that if an attack were launched, his troops could reach the north bank as quickly as possible. The whole operation was however only to be a blockade, as Ney wanted to concentrate on the various raiding units currently operating in his rear. However, the Allied crossing of the Elbe at Wartenburg on 3rd October rendered his strategy redundant and the French had to withdraw.

So ended a chapter from the Wars of Liberation, which has remained largely ignored.

Due to the unpopularity of the Swedish Crown Prince, the role of the Swedes in the Wars of Liberation engagements and battles had often been swept under the carpet in German books. Nevertheless, the policy of the Crown prince should not be equated with the willingness of his men to fight. In the battle of Roßlau, the determination of Swedish soldiers was clearly shown to be no less than that of their Prussian and Russian allies. In this battle, they could demonstrate it once more.

I should like to thank the following people for their help with my research: Alfred Umhey in Lampertheim for looking through and expanding upon the text; Klemens Koschig and Wolfgang Sefzik from Roßlau for providing the books mentioned below. I should also like particularly to thank Björn Bergerus from Stockholm for his untiring work in looking through the Swedish sources.

Quistorp – Die Geschichte der Nordarmee

According to Swedish works, the French lost 1,500 Mann, but this seems to be pure propaganda. The French were under cover for most of the time, and so cannot have lost anywhere near as many men as he exposed Swedes. In their regimental histories, the Swedes give a more detailed list of losses: Elfsborg Regiment: 4 men dead, 2 officers, 2 NCOs, 48 men wounded; Skaraborg Regiment: 1 officer, 1 NCO, 41 men dead,

9 officers, 9 NCOs and 220 men wounded; Västgöta Regiment: 1 officer wounded, numbers of men unknown.

|

Much has already been written about the great battles of the Wars of Liberation (1813-14). It is soon apparent that the Swedish troops took only a small part, or even did not participate at all, in these actions. This was mostly due to Crown Prince Charles John/Carl Johann (formerly Marshal Bernadotte) [1] wanting to preserve his forces for the campaign he planed against Norway, whose annexation had been his objective from the start, but for the time being, this had to be delayed.

Much has already been written about the great battles of the Wars of Liberation (1813-14). It is soon apparent that the Swedish troops took only a small part, or even did not participate at all, in these actions. This was mostly due to Crown Prince Charles John/Carl Johann (formerly Marshal Bernadotte) [1] wanting to preserve his forces for the campaign he planed against Norway, whose annexation had been his objective from the start, but for the time being, this had to be delayed.

During this lull in the campaign, the Allies advanced closer to the Elbe, bridges being thrown over the river at Elster, Roßlau and Aken. As early as 16th September, 100 Swedes crossed the Elbe and marched towards Dessau, where they found Cossacks had beaten them to it. On the same day, a force of about 1,000 Swedes from various units including 200 Värmland Jäger were advancing to reconnoitre the enemy positions. In small outpost units, these troops had been underway for a week and at the end of this period, came under fire during a nighttime advance on Wittenberg an had to pull back. During the resulting fighting withdrawal, in which the Värmland Jäger formed the rearguard, they lost 3 dead and 40 wounded. Following this clash, they fell back on Roßlau.

During this lull in the campaign, the Allies advanced closer to the Elbe, bridges being thrown over the river at Elster, Roßlau and Aken. As early as 16th September, 100 Swedes crossed the Elbe and marched towards Dessau, where they found Cossacks had beaten them to it. On the same day, a force of about 1,000 Swedes from various units including 200 Värmland Jäger were advancing to reconnoitre the enemy positions. In small outpost units, these troops had been underway for a week and at the end of this period, came under fire during a nighttime advance on Wittenberg an had to pull back. During the resulting fighting withdrawal, in which the Värmland Jäger formed the rearguard, they lost 3 dead and 40 wounded. Following this clash, they fell back on Roßlau.

The Cossacks suffered quite badly in the resulting engagement, but their opponents then withdrew. Behind the Cossacks, Schulzenheim’s brigade [6] marched into Dessau as the army advance-guard, together with a troop of Mörner Hussars and a battery.

The Cossacks suffered quite badly in the resulting engagement, but their opponents then withdrew. Behind the Cossacks, Schulzenheim’s brigade [6] marched into Dessau as the army advance-guard, together with a troop of Mörner Hussars and a battery.

On the other side, Ney had received information about the Swedes’ retreat, so as in the action at Wartenburg, he intended to drive his opponents back on their bridgehead. As he knew the Crown Prince, he was calculating on an immediate retreat by the Swedes. The first brigade (under Gruyer [11] ) from the 13th Division was thus sent the order to join the light cavalry in driving the Swedes back.

On the other side, Ney had received information about the Swedes’ retreat, so as in the action at Wartenburg, he intended to drive his opponents back on their bridgehead. As he knew the Crown Prince, he was calculating on an immediate retreat by the Swedes. The first brigade (under Gruyer [11] ) from the 13th Division was thus sent the order to join the light cavalry in driving the Swedes back.