The Battle of Raszyn

April 19, 1809

Introduction

by A. Ricciardielo, Poland

| |

At right: Battery under fire at Raszyn, by W. Kossak. N.B. The first 4-gun batery was privately raised by Count Potocki. The drivers shown here have green Kurtkas as opposed to the regulation slate gray.

It came about as part of the Austrian offensive against Napoleon in 1809 as a secondary theatre in Poland, where it was hoped that an incursion there would encourage any unenthusiastic allies of the French to leave their pacts. D'Este was allocated the 32,000 men and 94 guns of VII Corps on 5 March to accomplish the task.

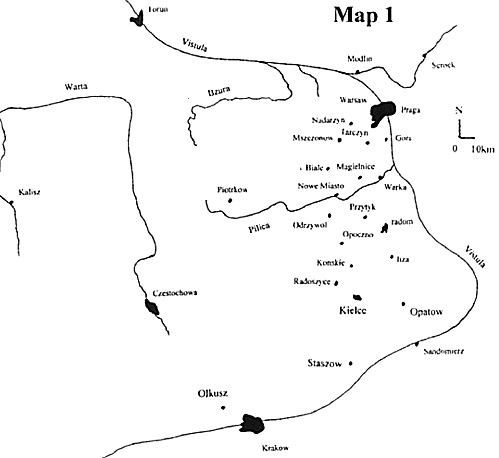

Initially the whole corps was to concentrate on Krakow (map 1) and take a defensive stance in Galicia in case of a Polish attack. Troop concentrations were achieved as quickly as possible with men being transported in wagons to the area. Krakow turned out to be inadequate as a sole base of supply, and importantly the Austrians were seriously worried about a possible popular uprising in that ancient capital of Poland. This was in the face of rumours of an approaching liberating Polish army. As a consequence, Ferdinand moved his bases to Sandomierz and Zamosc, and also repaired the walls, leaving strong garrisons there.

Ferdinand decided to move his men from Krakow through Malogoscz, Opoczno and cross the Pilica (the border with the Duchy and Austria) around Nowe Miasto. He wanted to attack Warsaw as quickly as possible and this was the most direct route. On the other hand intelligence reported that Zajonczek's division had moved to near Kalisz and Rawa, thus it was thought that the Poles might defend the line of the river Warta. If this was to be the case, then d'Este would take a more westerly route towards Olkusz and Czestochowa. General Mohr would then take Warsaw with a smaller force.

Charles replying to D'Este's letter secretly said that the Austrian operations would begin on 10th April, and told him to start earlier, on the 8th or 9th. He emphasised the need for quick successes, for reasons of army morale, and that any reverses would be disastrous to the whole coalition; meaning appeals to the German states, and a hoped for alliance with the Russians, too. Charles advised the corps to march into the heart of the Duchy from Krakow to Czestochowa to Piotrkow because, " the operation has a stronger influence on public opinion, the corps takes food on enemy soil, covers our border, the enemy is more confused.... " etc.

These suggestions were however ignored. On 27/28 March Speths brigade made for Kielce, and Vakassowich to Staszow. On 2 April d'Este ordered all divisional commanders to concentrate around Odrzwol, previously organised as a staging camp. The 2 brigades of Marshal Mondet went along the line, Malogoszcz, Radoszyce, Konskie, Opoczno. Wiedenfeld's cavalry divn. from Staszow through Kunow, Iliza, Radom, Przytyk. Davidowitch's brigade, Sandomierz to Opatow, then as Wiedenfeld. Branovach's brigade was allocated Czestachowa to take, concentrating in Olkusz on 10th April. Charles's advice was ignored, as it wasn't really practical. The letter sent out on 30th March setting out the 8th or 9th as an attack date was unrealistic. It was some 180kms to the Duchy from Krakow and the roads were not too good either. In addition, lingering at

staff H.Q. was very much the attitude of waiting to see what the Russians would do. In the event the concentration at Odrzymol, wasn't completed until 13 anyway.

Two squadrons of Mohr's covered and reconnoitred for the brigade which left Odrzywol at 8 a.m. 14 April, the day d'Este arrived. D'Este sent a proclamation of war addressed to Poniatowski stressing that he didn't consider the Duchy as an enemy, but his mission was to defeat Napoleon. He urged the Poles to join him as they were being no more than manipulated by Napoleon.

If there was anything of merit at all considered by the Poles in this letter, it was all ruined by his ending, which referred to a return of power to all monarchs. This of course meant a return of foreign rule in a dismembered Poland. This letter delivered by 2nd Leutenant Joseph Taczany and received by 2nd Leutenant Jan Krasnicki of the 1st Chasseurs a Cheval also informed of the forthcoming invasion within 12 hours. At 5am, 15th April, VII Corps crossed the river Pilica.

If the Austrian H.Q. did not behave with quite a sense of urgency as advised, the Poles weren't exactly on the ball either. Despite accumulating intelligence reports that the Austrians were conducting offensive operations, these were largely treated with disdain.

Poniatowski even sent a report to Davout saying that the Austrians wanted to tighten up in Galicia with no other real intentions. In effect a little bit of local sabre rattling.

This attitude had its roots in orders sent to Poniatowski on 4 March from Napoleon ordering a concentration around Warsaw and stop the enemy there should they invade at all in the future, and that in any case there wouldn't be any moves without a Russian alliance. The Polish inaction clearly shows a willingness to believe all Napoleon said as gospel. The resulting lethargy and lack of clarity came from a deep belief in Napoleon's words, over and above the evidence of the ground reports. Poniatowski limited himself to minor organisational changes and

recruitment. The latter largely was failing due to a lack of money. He did however provision the strong points, but the one thing he did not do was to complete their fortification, not even in Warsaw. Possibly this had something to do with money too. Were the Poles to have done this they could have crossed the Vistula at will and operate on either bank as they wished, obliging the Austrians to blockade these points and be split.

However, on the 11th April the first concrete orders came to concentrate all forces on Warsaw. These were later cancelled the same day. Instead General Bieganski was ordered to Raszyn with two battalions 3rd regiment, 2 x 6pdrs and 2 x howitzers. The 6th Lancers also in his command covered the front at Nadarzyn.

On the 12th Roznicki was ordered to deploy the 1st and 3rd cavalry along the line Tarczyn, Mszczonow, Gora. In addition a couple of battalions, were sent to Warsaw (8th from Modlin and 6th Serock). Also on the way to Warsaw was 12th infantry joining the 1st and 2nd infantry, the 2nd Uhlans and elements of artillery already there.

The last part of these initial moves was to send Col. Mallet head of the engineers on 13th April to the Nowe Miasto area to report on the roads the Austrians could use. He did reach his destination, but not in time to finish his job; he was told that war had already started.

The tardiness of these Polish moves, the realisation of Raszyn as suitable for defence and relatively late occupation of it, indeed the overall appreciation of events just did not sink in till late at the Polish high command. The strong belief in Napoleon's views led them to be taken aback by events and unprepared in the time frame they would have liked. The Austrian forces meanwhile had been broken into three and crossed the Pilica making for Rawa. The first group under Brenowecksky (3,352 foot, 1,042 horse) blocked the fortress of Czestochowa and was to move to Warsaw once established with any troops deemed superfluous to his goal. The main body under d'Este (25,365 foot, 3,671 horse) moved straight

to Warsaw for a decisive battle. To the left of this main group Major Hoditz marched with 8 hussar squadrons and 1,042 foot.

By this time d'Este had learned that the Bzura wouldn't be defended and that virtually the whole Polish army was about Raszyn. He therefore didn't have quite so far to go. This helped because the supposedly quick march was slowed because of poor roads made worse by very wet conditions, stringing out the columns.

Poniatowski sank into a state of gloom and was acutely aware of the responsibilities shouldered upon him. He started to blame Napoleon for the invasion and realised only too well that public opinion would make him the scapegoat for any defeat. He even felt that saving the life of Prince Schwarzenberg, when fighting the Turks went against him, as he (Schwarzenberg) was now a sworn enemy of Poland. However, with the passing of a little time and the support of a French resident in Warsaw, Serra, Poniatowski overcame his despondency and galvanised himself; he even started to look forward to the contest. He realised that the army was enthusiastic, and he himself was very well thought of. He rejected advice to fall back onto Warsaw, in case the army might become demoralised and very boldly considered taking the initiative. Obviously not certain of Austrian intentions The Poles did however believe that they would seek a decisive battle and take Warsaw. They also thought that the route taken would be Biala, Tarczyn.

On 15 April Poniatowski arrived at Raszyn and sent his plans to Bernadotte. He would defend Warsaw with all available forces, and also

garrison Serock, Modlin and Praga. On from this, with mostly cavalry he would seek to raid for provisions in Austrian Galicia and provoke a popular uprising, hopefully encouraging the enemy to leave the Duchy. With a definite plan in place, Roznicki moved forward from Tarczyn

and passed Mohr's force by 12kms west on the other side of a wood. The bulk of the Austrians crawled forward on the appalling roads.

Further information was sought on the Austrian whereabouts by sending out more cavalry towards Mszczonow and along the banks of the Vistula. On 17 April the first skirmishes took place. One near Coniew resulted in the death of Taczany, the bearer of the declaration of war. In the face of greater numbers the Polish cavalry sensibly withdrew. This encouraged some criticism of Roznicki especially from the lower ranks whose morale was very high, and they were itching to prove their mettle. A contemporary writes on a skirmish, "Not only were some flankers wounded during the skirmish with the Hungarians, but some Hungarians were wounded as well. It caused great joy amongst our soldiers."

Complaints about Roznicki included; too slow, too cautious, and can't report to H.Q. on Austrian whereabouts. In all fairness this last point was very difficult to do because the terrain was very wooded. intact, although Roznicki can he criticised for several things, these comments in this situation are unjustifiable.

It was eventually established that the Austrian columns were marching from Biala to Tarczyn. With the line of Austrian march verified, all outlying units were drawn in and around Raszyn, leaving Roznicki to observe the invaders. Mohr was ordered at this time to take Mszczonow and watch the road to Blonie in case of a Polish attack from the Bzura.

Poniatowski's position was very good. It blocked the road to Warsaw and the Austrians had to go through a belt of ponds and marshes 600 to 2000 metres wide. Furthermore, they would have to cross a river, (Mrowa) albeit small, but with very muddy banks. To make matters more difficult, that year's thaw had set in late keeping the water level high. Given this terrain, the Austrian army was effectively obliged to cross at

three points:- Jaworowa, Raszyn, and Michalowicz. Thus, of the 6km stretch, the Poles really only had to defend these three places to block the way to the capital.

The pivot of the defender's position was the High Post Road from Tarczyn to Raszyn, passing by the Wygoda Inn and the manor house at

Falenty then along a wide dyke to Raszyn itself. The other main road went through Janki to the west, which in turn converged on Raszyn. To the cast of the Raszyn High road was the village of Falenty Male with the early baroque manor, and to the south west of this, Falenty Duze. Between these places was an Alder wood.

|

What is now a rather untidy suburb of Warsaw, Raszyn (pronounced rashin) saw a gritty fight between the forces of Prince Joseph Poniatowski, and Archduke Ferdinand d'Este on April 19 1809.

What is now a rather untidy suburb of Warsaw, Raszyn (pronounced rashin) saw a gritty fight between the forces of Prince Joseph Poniatowski, and Archduke Ferdinand d'Este on April 19 1809.

Whilst all of this was going on, Ferdinand on 23 March wrote to Archduke Charles informing him of his plans. D'Este wanted to attack along the left bank of the Vistula River, as an attack along the right bank would ultimately bring him up against the strong points of Serock, Praga and Modlin.

Whilst all of this was going on, Ferdinand on 23 March wrote to Archduke Charles informing him of his plans. D'Este wanted to attack along the left bank of the Vistula River, as an attack along the right bank would ultimately bring him up against the strong points of Serock, Praga and Modlin.

Once this concentration was complete, Mohr with 4,485 infantry and 1,042 horse was told to go to Nowe Miasto on the Pilica, avoid any serious fighting and collect a few prisoners to learn of Polish troop whereabouts. At this juncture d'Este thought that the line of the river Bzura might be defended. He knew the Poles had left Warsaw but had no real idea where to. As a result of these doubts Mohr was ordered to march towards Warsaw through Biala rather than Magielnice and Tarczyn. This would bring him more to the west than south of Warsaw.

Once this concentration was complete, Mohr with 4,485 infantry and 1,042 horse was told to go to Nowe Miasto on the Pilica, avoid any serious fighting and collect a few prisoners to learn of Polish troop whereabouts. At this juncture d'Este thought that the line of the river Bzura might be defended. He knew the Poles had left Warsaw but had no real idea where to. As a result of these doubts Mohr was ordered to march towards Warsaw through Biala rather than Magielnice and Tarczyn. This would bring him more to the west than south of Warsaw.

Immediately to hand, Poniatowski (at right) had only 14,000 men; the 12th hadn't arrived as their orders hadn't been written out promptly. Much worse though was a measure of panic that had broken out in the city and no placatory morale boosting proclamations had been made to alleviate this situation. The Polish authorities were used to receiving orders from Dresden and Paris, and not issuing them themselves. They were ill equipped to face up to the stress and demands of the situation; an invasion. They were caught with their pants down, and were in the least,

flustered.

Immediately to hand, Poniatowski (at right) had only 14,000 men; the 12th hadn't arrived as their orders hadn't been written out promptly. Much worse though was a measure of panic that had broken out in the city and no placatory morale boosting proclamations had been made to alleviate this situation. The Polish authorities were used to receiving orders from Dresden and Paris, and not issuing them themselves. They were ill equipped to face up to the stress and demands of the situation; an invasion. They were caught with their pants down, and were in the least,

flustered.