The French Skirmisher

Tirailleurs De Route et de Combat

With Diagrams (Very Slow: 372K)

By John Cook, UK

| |

I also pointed out that the Règlement 1791 had little to reveal about how the French skirmished, indeed the only mention of skirmishing appears towards the end of the document where it describes the movements of columns.

“The column being in this order, the Commandant en chef will resume the march in pas de route or pas de cadence, and will detach, if he judges it necessary, some men of the third rank of the divisions, who will be placed on the two flanks, at fifteen or twenty paces from the column, and will fire at will on the hussars or enemy cavalry which approaches within musket range; these skirmishers will follow the march of the column, abreast of their divisions, the cannon will march between them, to approximately eight or ten paces from the column.”. [1]

The Règlement 1791 is describing tirailleurs de route whose mission was to carry out reconnaissance, screen the flanks and heads of columns on the march, seize vital ground and engage the enemy, but it tells us nothing about how they skirmished when the enemy approached “within musket range”. It is, nevertheless, and important passage because it does indicate where skirmishers (Tirailleurs) were probably drawn from prior to the establishment of the voltigeur company.

Ney’s Instructions to the Left Corps tends to confirm this. He describes how when marching in column the third ranks might be detached and march to the left or right rear of divisions from which they are drawn, for employment as Tirailleurs as necessary. His instruction conforms, more or less, with the meagre mention of skirmishers in the Règlement 1791. [2]

The Règlement 1791 and Ney’s Instructions were, of course, written prior to the formation of Voltigeur companies but even during the Imperial period the third rank was evidently still used as a source of skirmishers if necessary. General Brenier, writing in the Spectateur Militaire, described how when it became necessary to provide additional skirmishers to replace the voltigeur company covering the front, that a number of men from the third rank of each fusilier company were detached for this duty. [3]

So, in addition to the specialist company, it is clear that fusiliers were perfectly capable of serving in the light role and, furthermore, the third rank continued to be a source of additional skirmishers.

Also briefly discussed in the original article was Davoût’s instructions, as described in George Nafziger’s Imperial Bayonets, which were assumed to be typical of the Imperial period, and it was observed that French controlled skirmishing appeared to be a similar procedure to that used elsewhere, that is to say a deployed open order skirmish line, close order supports and a close order reserve. I further commented that if there was an official doctrine for disciplined use of skirmishers in the French service, it seemed to have been largely unrecorded.

Since writing that article I have acquired a copy of Davoût’s instructions and it is now possible to examine these in rather more detail; they appear to have been the work of General Morand. [4] In addition, three other documents dating from the Imperial period have also come into my possession and, although these appear to be individual initiatives, like Davoût’s, it is now evident that doctrine for French skirmishing was far from unrecorded, such that it is now possible to determine, I think, how the French skirmished during this period with a fair degree of accuracy.

But before looking at the detail of these documents it is probably worth establishing exactly what this article is concerned with.

The generalities of French skirmish doctrine are discussed at some length in Bressonet’s Etudes Tactiques sur la Campagne de 1806. [5] There was a distinct division of tirailleurs into two categories. The first was tirailleurs de route et de combat, which I shall translate as ‘skirmishers on the march and in battle’ the second was tirailleurs en grande bande, which roughly means ‘skirmishers in a large group’. Tirailleurs de route et de combat always remained subordinate to and functioned on behalf of the battalion from which they were detached; tirailleurs en grande bande did not.

Tirailleurs en grande bande, on the other hand, are described as a “corps principale” and are quite different in function from the tirailleurs de route et de combat. The Tirailleurs en grande bande comprised an entire battalion, or numbers of battalions, broken down into open order and used as an assaulting formation where man-made features or terrain, such as buildings or woods and so on, precluded the used of formed columns or lines. Tirailleurs en grande bande were not used for reconnaissance, screening or preparing an attack - they were a main attacking force. This article is concerned with tirailleurs de route et de combat.

To return to Davoût’s instructions, which were disseminated to generals Friant, Gudin, Dessaix, Compans and Barbanégre at Hamburg on 16 October 1811, they note that the voltigeur companies which were “elite companies” could not always undertake the skirmishing role without “serious inconvenience” and that other companies should be trained to do so and, furthermore, that this should apply to line regiments as well as light. The instruction was disseminated to all brigade commanders and colonels commanding regiments and ordered that fusiliers should be trained together with voltigeurs. It does not elaborate on what the “serious inconvenience” was in the context of voltigeur companies or why their being “elite companies” was an issue.

Be that as it may, the method by which skirmishers functioned when covering a column or line was as follows.

The skirmish company was divided into three sections; right, centre and left, commanded by a captain. This is interesting because the normal division of a company was into two sections. It might, however, be a convenient division if the skirmish company was an ad hoc sub-unit taken from three different companies, perhaps from the third ranks, but I emphasise that I am merely speculating. On the other hand, as we shall see, the typical deployment of a skirmish company was in three elements.

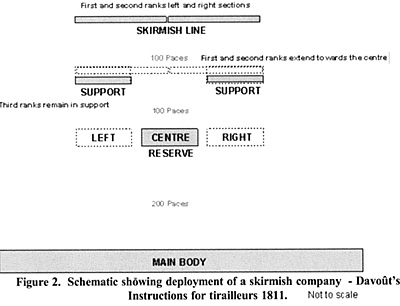

The skirmish company first marched to a point 200 paces from the parent battalion where it was halted on the centre of the position it was to cover. The centre section remained at the 200 pace point in close order as the reserve, with the captain commanding, the sergeant-major, two sergeants, two corporals and two drums or horns. The remaining right and left sections, commanded by a lieutenant and sous-lieutenant respectively, marched forward a further 100 paces on the right and left and halted. The first and second ranks of the right and left sections then faced to their left and right respectively and marched towards the centre until they met with a distance of 15 paces between files.

They then faced towards their front and marched forward at the pas ordinaire (76 paces to minute) a further 100 paces.

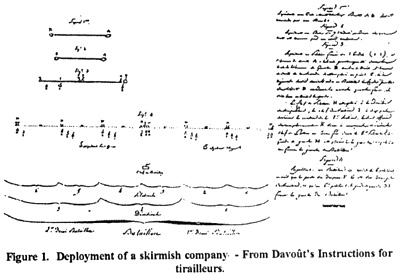

The third rank of the right and left sections remained at the halt in close order to provide a support to the skirmish line. Thus the skirmish company formed the classic three component parts. A close order reserve formed by the centre section, a close order support to the skirmish line formed by the third rank of the right and left section, and the open order skirmish line formed by the first and second ranks of the right and left section. Davoût’s somewhat indistinct original diagram, which accompanied the instruction, is at Figure 1 and my interpretation showing the movements (open dotted symbols) and final dispositions (shaded symbols) is at Figure 2. Please note that my diagrams are to not scale and are purely schematic.

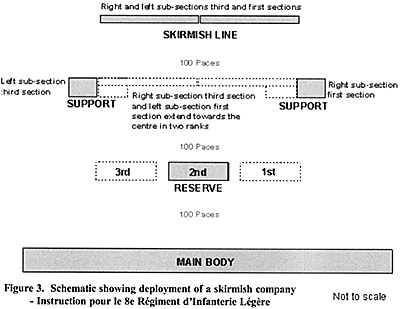

These instructions more or less follow what was done by skirmish of other nationalities, but the distance between the main body and the skirmish line is rather more that in other French instructions, the latter being 400 paces in front of the former. This is because the point at which the skirmish company starts its deployment is 200 paces from the main body, rather than the more common 100 paces, as we shall see shortly. Of particular interest is that the main body in Davoût’s original sketch is shown as a battalion with six companies. It is unclear where the skirmisher platoon was drawn from and the only possible conclusion is that is was from another battalion or possibly formed from the third ranks of companies in the parent battalion. Other points to note are that the skirmishers always work in pairs and only fired one at a time so that one was always loaded. When covering a column the skirmish line formed an arc, part of a circle the centre of which was the centre of the head of the column. When covering a deployed battalion the skirmish line was parallel to the battalion. Finally, training was to be carried out using the pas accéléré (100 paces to the minute) and pas de course (150 paces to minute), the latter being the pace adopted for all changes of direction and front. The Instruction pour le 8e Régiment d’Infanterie Légère - Manoeuvres des Tirailleurs gives similar instructions to form reserve, supports and skirmish line. The skirmish company was divided into three sections like Davoût’s, but called 1st, 2nd and 3rd, each comprising two sub-divisions. To cover a battalion in column the Skirmish Company marched forward as before, but to a point 100 paces from the parent battalion, rather than 200 paces as described in Davoût’s instructions. The 2nd section formed the reserve, with which the officer commanding the company remained, whilst the 1st and 3rd sections executed a 45 degree turn right and left and marched forward 111 (sic) paces at the pas de route (90-100 paces to the minute) and halted facing the front. I cannot explain why 111 paces is specified. The 2nd (left) sub-division of the 1st section filed to the left and the 1st (right) sub-division of the 3rd section filed to the right and formed a two rank skirmish line with six paces between files. This line was then taken forward a further 100 paces at the pas de course by the officer commanding the 1st section. A diagram is at Figure 3.

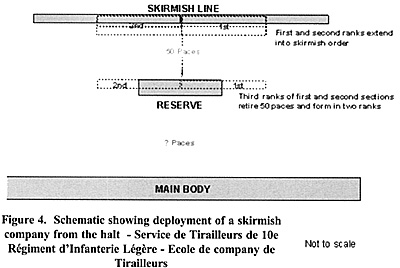

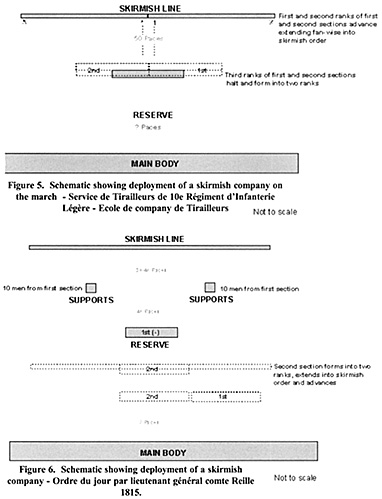

For covering a battalion in line the methodology was the same but the distance between the three elements of the skirmish company was increased to 150 paces rather than 100 (or 111), which pushed the skirmish line out to 450 paces from the parent battalion. Also of interest is Article 9 of 8e Légère’s instruction which describes how skirmishers could be ordered to lay down, on their left side, and fire from the prone position. The instructions in the Service de Tirailleurs de 10e Régiment d’Infanterie Légère - Ecole de company de Tirailleurs gives distances rather less than the two examined so far. It also describes hoe to deploy a skirmish company initiall formed in three ranks and interestingly, in two but although it states that the usual distance between skirmish files was ten paces, it does not say how far the reserves was from the main body. It gives methods for deployment from the halt and on the march. The skirmish company had two sections. When deploying from the halt the first and second ranks of the 1st and 2nd section turned to the right and left respectively. The third rank of the company about-turned and was marched 50 paces to the rear by the company sergeant-major and formed in two close order ranks as a reserve. At the same time the flank files of the two sections marched to their respective flanks in file, the line being halted when the it was sufficiently extended. The distance between the first and second rank was one pace, the distance between files is not given except to say that they were to be indicated when the skirmish line was formed. Corporals were posted and the end of each rank in the skirmish line and the captain commanding the skirmish company remained with the reserve. Deployment was done at the pas de course. A diagram is at Figure 4. Forming the skirmish line on the march was done slightly differently.

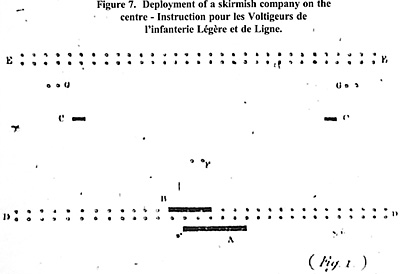

The third rank halted and formed into two ranks. The first and second ranks continued in line for fifty paces at the pas de course, the centre file marching directly forward whilst those to the flank gradually extended the flanks fan-wise as they marched. On arrival at the required point the skirmish line was halted and dressed by the captain commanding. A diagram is at Figure 5. When deploying a skirmish company formed in two ranks the reserve was taken from files on either flank, providing an equal number of men to those in the skirmish line. When deploying from the halt these flank files about-turned and retired 50 paces, when deploying on the march they halted and closed on the centre whilst the skirmish line advanced. The principal difference in the method used by 10e Légère is that the skirmish company only has two elements, a reserve and the deployed skirmish line, and does not appear to include supports. In the Ordre du jour par lieutenant général comte Reille in 1815, the skirmish company also has two sections and is stationed “a few paces” from the parent battalion. One of the sections, for arguments sake the 2nd section but it could be either, was sent forward to an unspecified distance halted and the flank files marched left and right to a distance of 10 to fifteen paces, when the next two files follow them, and so on. When the flank files had reached 20 or 30 paces the flank march by files was halted. At the same time two groups of ten men from were detached from the 1st section and sent forward as supports 30 to 40 paces behind the flanks of the skirmish line. The remainder of the first section formed the reserve and was posted 40 paces to the rear of the supports. An illustration is at Figure 6.

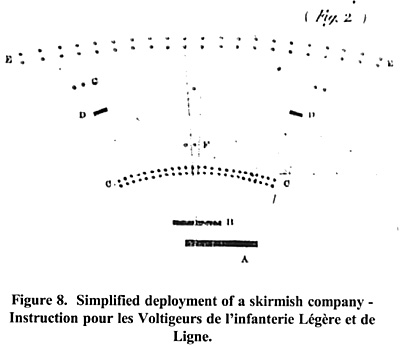

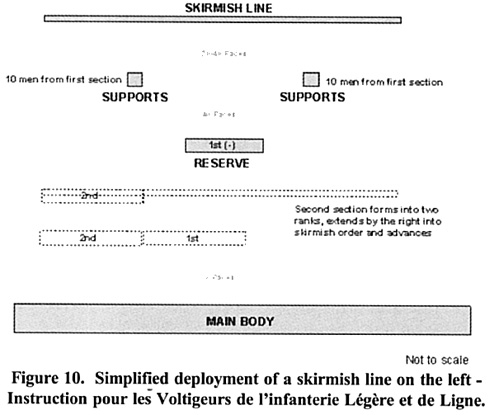

A final document worth examination is post-Napoleonic but it clearly reflects Napoleonic practice. This is the Instruction pour les Voltigeurs de l’infanterie légère et de Ligne which was written by an officer who had served in the Grande Armée and was published in Paris in 1822. It was translated into German in 1823 by a Württemberg Schützen officer, with his additional comments. This gives two different methods for deploying skirmishers. The first is described as forming the skirmish line from the centre. It is similar to that used by Reille. The company detailed to provide skirmishers was detached from the parent battalion and when a few paces away the order was given for one of the two sections to advance and form the skirmish line in two ranks. The order being given to right and left turn, the files on the right and left flanks march in file to the flank to 10 to 15 paces, followed by the remainder. When the two files either side of the centre file were approximately 20 paces apart, the skirmish line was halted, faced towards the front and advanced onto the position where it was required. The other section, in reserve, then sent two groups of ten men each to a position 30 to 40 paces in the rear of the right and left flanks of the skirmish line as supports. The reserve section remained 40 paces behind the two supporting groups. An illustration from the Instruction is at Figure 7.

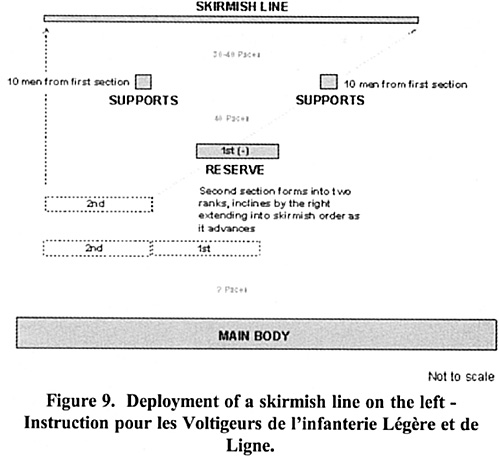

The Instruction also describes a simplified method of deployment and states that the method of deployment on the centre was too time consuming. In the simplified method the company detailed for skirmish duties was detached from the parent battalion as before and formed into two ranks. The section forming the skirmish line was advanced as before but the line was formed by the centre file marching ahead whilst the others marched fan-wise until the position to be occupied was reached and the files were approximately ten to 15 paces apart. This is not unlike the method used by 10 Légère on the march. An illustration is at Figure 8.

SummaryIn summary, most methods describe the familiar arrangement seen for deployment of skirmishers everywhere, that is to say, a deployed skirmish line, close order supports to the skirmish line for rotation through it, or to reinforce it, and to provide an initial rallying point, and a close order reserve on which the skirmish company as a whole might rally or reform prior to rejoining the main body of the battalion. The Service de Tirailleurs de 10e Régiment d’Infanterie Légère, uniquely, seems to omit the supports and only features a reserve. More or less common features in all the documents are as follows.

2. Deployment and movements by the skirmish line are generally at the pas de course, which the Instruction pour le 8e Régiment d’Infanterie Légère gives as 150 paces to the minute. Other cadences encountered during the deployment of the Skirmish Company are the pas de route, 85-90 paces to the minute and the pas accéléré at 100 paces to the minute. 3. The captain commanding the Skirmish Company remains with the reserve. 4. Maintenance of communication between the elements of the deployed skirmish company is stressed, particularly between the skirmish line and the reserve. 5. Emphasis on tight control of the skirmish line through a variety of drumbeats and bugle calls. 6. The captain commanding the Skirmish Company had to follow the movements of its parent battalion and at the same time conform to the enemy threat. 7. In the event of threat from cavalry, the skirmish line formed a clump, or a circle, on the centre and rallied on the supports and, ultimately the reserve which moved forward. 8. Emphasis is placed on the use of terrain and cover. 9. Bayonets were removed when on the skirmish line, but fixed when in support or reserve. 10. One of the two soldiers in each file on the skirmish line should always have a loaded weapon. In summary it is possible to say, I think, that all types of French infantry during the Imperial period were expected to be able to skirmish if required and that a number of methods, but all variations of a single theme, were in use. The methods described in all the documents give a picture of controlled French skirmishing similar to that found in the armies of other countries at the time which is quite unlike the received wisdom of anarchic French skirmishing. Footnotes[1] Règlement Concernant L’Exercice et les Manoeuvres de L’Infanterie Du 1er Août 1791. Paris 1792. Titre V, Evolutions de ligne, cinquiéme Partie, para 568, p 565. ‘Colonne contre la cavalerie.’.

|

Some time ago I wrote an article for First Empire describing the use of the third rank, a principal function of which in many armies was to provide skirmishers. In that article I made the observation that of all the nations involved in the Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars, the French, who have the greatest reputation where skirmishing is concerned, had left us least on the subject in any of their official documents.

Some time ago I wrote an article for First Empire describing the use of the third rank, a principal function of which in many armies was to provide skirmishers. In that article I made the observation that of all the nations involved in the Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars, the French, who have the greatest reputation where skirmishing is concerned, had left us least on the subject in any of their official documents.