The Night Attack

The Battle of Talavera

27-28 July 1809

By Terry Crowdy, UK

Illustrations Terri Jullians

| |

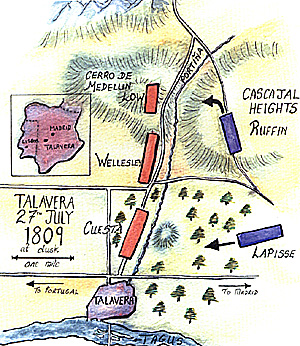

This article is not an account of that battle in its entirety, but looks exclusively at one famous incident that happened the evening before the main attack. The story is told in the most part by two combatants: Lieutenant Girod [9è Régiment d’Infanterie Légere] from the French side, and Sergeant Nichol [1st Battalion Detachments] from the British. Between them they give a clear picture of the events that night and also offer a glimpse of the confusion of Napoleonic combat in the dark . . . On the afternoon of the 27th July 1809, the two armies first came into conflict as Marshal Victor brought forwards the lead elements of the French. Around 4 p.m. on the afternoon of the 27th, the 9è Léger reached the banks of the Alberche River. The 16è léger had already crossed over to the far bank and had come to grips with the British advanced guard. Hidden by a forested and broken terrain, the soldiers of the 9è could not see the engagement, but they could certainly hear it. Lieutenant Girod recalled: ‘It was the first time that the noise of an English fusillade had come to our ears.... indeed never had we heard a rolling fire as well fed as that.’ The 9è Léger and the rest of the Division Ruffin [24è and 96è de ligne] moved forwards in support of their comrades, fording the Alberche with, as Girod put it, ‘the water up to our armpits.’ Behind the British advanced-guard, work was underway preparing a defensive position to the north of Talavera. Among some olive trees Sergeant Nichol of the 1st Battalion of Detachments was with a working party constructing a battery on rising ground. From his position he had a clearer view of the clash between the two advanced guards: ‘[The] French arrived at the side of the Alberche, and opened fire on our advanced guard, fording the river at the same moment. We kept them in check; but from where I was I could see that our people were suffering much, and retiring to take up their position in the line. The working parties were ordered to stand to their arms, as the shot from the French was coming thick among us. We were then ordered to join our regiments as quickly as possible, and we joined our battalion on the side of the hill to the left of the line.’ While the French probed the Allied right, the Division Ruffin took up a position on the Cascajal heights. At the same time, Marshal Victor rode up to take a look at the positions that Sergeant Nichol had helped prepare. Having been at Talavera not long before, Victor was well acquainted with the local terrain. He knew that the key to the coming battle would be the Cerro de Medellin, a hill on the left of Wellesley’s line. Victor foresaw the difficulty his troops would have storming this hill in broad daylight and so formulated a daring but hazardous plan to seize it under the cover of night. Ruffin’s Division, containing Victor’s most trusted men, was charged with the capture of the Medellin. While Lapisse’s Division mounted a noisy demonstration against the Allied centre, Ruffin’s Division would descend from the Cascajal heights into the Portiña Ravine. From there the 9è Léger would assail the front slope of the hill while the 24è swung round the right and the 96è the left of it. If the plan worked and the hill was taken, Victor believed that the morrow’s battle would already be half won. Diversionary Attack As the evening drew to a close, Lapisse mounted his diversionary attack. Nichol, on the left of the line at the foot of the Medellin recalled: ‘The firing on the right ceased after dark, when the French made a charge of infantry without success. From the place where we stood we could see every movement on the plain.’ Nichol was clearly looking the wrong way and like everyone else, had failed to notice Ruffin’s march into the ravine on the left. With its third battalion marching a little way behind in reserve, the 9è Léger prepared to advance: [Girod] ‘It was almost night, when Colonel Meunier received the order to prepare the attack of this hill; he made us load our arms and formed our two battalions in columns marching level with each other. It was near 10 o’clock in the evening and the darkness was complete; when we began to climb the hillside, its slope, gentle enough at first, soon very became abrupt.’

On the reverse slope of the Medellin, the aptly named General Hill was issuing orders to the Colonel of the 48th when he heard firing coming from the top of the Medellin. Considering the incident to be nothing more than [Oman V.II p.518] ‘.. the old Buffs, as usual, making some blunder’ Hill, and Brigade-Major Fordyce went off to investigate. The 9è Léger had meanwhile reached the crest of the Medellin but only in great disorder. Some officers tried to rally their men [Lieutenant Girod could only find 18 of his company], while Chef de Bataillon Réjeau sent voltigeurs to reconnoitre ahead and link up with the rest of the Division which was presumed to be coming up in support. As General Hill rode forwards, musket balls began flying past him with increasing frequency. Somewhat annoyed, he called out to the nearby troops, whom he assumed were British and told them to cease their firing. He was somewhat surprised therefore when one of these fellows grabbed him by the arm and bade him to surrender. Hill spurred his horse forwards and broke free from the voltigeur’s grip. The Frenchman levelled his musket and fired after Hill, wounding his horse. Others opened fire blindly in the dark, killing Fordyce but somehow missing Hill as he galloped off to safety. Sergeant Nichol meanwhile had been waiting for the biscuit ration to be distributed. Supper was cancelled however as a cry went up: [Nichol] “The hill! the hill!” General Stewart called out for the detachments to make for the top of the hill, for he was certain that no regiment could be there so soon as we. Off we ran in the dark, and very dark it was.’ On top of the Medellin, Réjeau was getting impatient for the arrival of the rest of the Division: [Girod] ‘The first thought of our battalion commander had been to try to reconnoitre the position; but, our attack not having been supported by other troops, he did not delay to be convinced of the impossibility of remaining there; indeed, thick masses of enemy infantry advanced in the shadows and looked to envelop us; already, came to us some English scouts who, fearing to be deceived in the darkness, approached us by pronouncing, with an interrogative tone, the word: ‘English...?’ Several of the 9è’s soldiers responded to these challenges somewhat mischievously: [Nichol] ‘[The] French had got on top of the hill before us, and some of them ran through the battalion, calling out, “Españioles, Españioles,” and others calling “Allemands.” Our officers cried out ‘Don’t fire on the Spaniards.” I and many others jumped to the side to let them pass down the hill, where they were either killed or taken prisoners in our rear. I saw those on top of the hill by the flashes of their pieces; then we knew who they were; but I and many more of our company were actually in the rear of the French for a few moments, and did not know it until they seized some of our men by the collar and were dragging them away prisoners. This opened our eyes, and bayonets and the butts of our firelocks were used with great dexterity - a dreadful mêlée.’ As Nichol’s comrades were snatched out of their ranks and dragged off up the Medellin, their appearance awoke the curiosity of Girod and his companions: ‘We had found and made captive approximately 200 Scots in Kilts (these were first that we had ever seen) and we had also seized two cannon.’ At the Foot of the Medellin, General Hill had put himself at the head of the 29th and was leading them up to help the detachments who had fallen into a terrible muddle. Réjeau meanwhile, still with no news of the rest of the Division, had seen enough: [Girod] ‘.... Finally, we heard the command ‘Demi-tour’ pronounced by our chef de bataillon and, abandoning a part of our prisoners, but retaining the two cannon that we had taken, we re-descended the slope of the hill in some disorder; I remained in the rear with the most of the officers, my comrades, we all made efforts to slow the race of our men by shouts of: ‘Halte! Halte!’ As the first two battalions fell back, the third battalion made a belated appearance coming round the side of the Medellin, marching diagonally across the British left. General Hill directed the 29th to deliver a volley in the third battalion’s flank forcing it back towards the Portina ravine. Nichol: ‘The enemy tried it a second time, coming round the side of the hill; but as we now knew who they were, to our cost a well-directed running fire, with a charge, sent them into the valley below, their drums beating a retreat.... The firing ceased at eleven o’clock; all was silent on the plain before long.’ The fate of the rest of Ruffin’s Division in this night attack is not unsurprisingly a little muddled. As the Division entered the Portiña Ravine and split up, it seems that the three battalions of the 24è, became lost in the darkness and wandered up the valley between the hill and the northern mountains without coming into action at all. The 96è meanwhile, entered a part of the Portiña ravine, which was very precipitous, and were heavily delayed climbing up the other side. They became partially engaged with the 5th and 2nd battalions of the King’s German Legion, which ended when the fighting on the hill above them ceased. Aftermath [Girod] ‘The enemy did not follow us, and all our men stopped when almost halfway down. There, we reformed, and some willing men ascended high enough even to seek out and bring back our wounded; a good number of these last were thus returned us; the rest fell into the hands of the English.’ Of these soldiers, 65 were taken prisoner by the British, including it seems the Colonel. Meunier had been hit three times in the volley fired by the K.G.L. at the commencement of the action and had either been lost in the confusion or seemingly too badly wounded to be moved. (Meunier’s capture was not officially reported by either side, but instead is reported by Leslie of the 29th: [cited by Oman V.II p.518] Being recovered, along with the other prisoners, when Talavera was evacuated, his name did not get down among the list of missing, which was only drawn up on the 10th August.)

The silence did not last for long however: [Nicol] ‘About one in the morning we could hear and see the French moving their artillery on the other side of the hollow about two hundred yards from us. Some firing commenced; it ran from the left to the right for we could see every flash in the plain below us.’ This sudden volley traumatised Girod greatly: ‘Just as we were we lulled, a stronger fusillade woke us in a start. I was soon on my feet, but one must judge the terrible moment that I passed: I felt seized by the trembling of my limbs, my knees knocked between themselves - my teeth chattered, I could not articulate a sound and I saw, around me, my men apparently in the same situation as me and as taken in panic, causing them to flee, abandoning their havresacs and their guns! It was the freshness of the night that, in the circumstances that I have told, had seized us and put us in this unspeakable emotional state. Finally, after a few moments, forcing myself to snap out of it, I managed to make myself heard and rallied my men; I ran to visit my positions to learn the cause of this awful alert, I found my sentries in their place and perfectly tranquil; they had also heard a lively fusillade and some had even seen flashes in the distance, but without being able to explain it. It was, apparently, two enemy corps that, operating in the darkness, had taken each other for adversaries and had fired on one another. Everything having returned to silence, I regained the main body of my troop and spent, the rest of the night very peacefully in the middle of it.’ This abrupt spate of firing was explained in the 1st corps Journal [cited by Loy p.324] as: ‘the enemy, rendered mistrustful by the attempt of Ruffin’s Division and believing without doubt that a new attack was coming, suddenly opened fire along all the line, then all returned to silence.’ This would be the last action of the night: [Nicol] ‘Order was restored, and a deathlike silence reigned among us.’ Lieutenant Girod goes on to report an occurrence that was by no means unique between English and French soldiers in the Peninsular War: ‘A small brook flowed a few paces in front of my sentries; the need for water attracted there, from one place or the other, Englishmen and Frenchmen, who calling a truce to their hostilities, came during the whole night to drink there and to draw there in good terms.’ As the sun rose, both sides could for the first time make out the ground they had fought over the night before. Examining the field Nicol remembered: ‘Round the top of the hill many a red coat lay dead; about thirty yards on the other side the red and the blue lay mixed, and a few yards farther, and down the valley below, they were all blue.’ The casualties sustained by the 9è Léger were put at about 300 men, including the 65 prisoners already mentioned. Oman states that the British suffered slightly heavier losses: The K.G.L. losing 188 men, 87 of whom were made prisoner, while Stewart’s brigade admitted the loss of 125 killed and wounded. Marshal Victor’s gamble had failed and his attempt to seize the initiative for the day of battle had failed. Was he at fault for ordering an operation fraught with so many difficulties, manoeuvring a Division uphill, over broken ground in pitch darkness? Oman thought so and instead put praise on the soldiers of the 9è léger for getting as far as they did: ‘Thus ended, in well-deserved failure, Victor’s night attack... To attack in the dark across rugged and difficult ground was to court disaster. The wonder is not that two-thirds of the division went astray, but that the other third almost succeeded in the hazardous enterprise to which it was committed. Great credit is due to the 9th Léger for all that it did, and no blame whatever rests upon the regiment for its ultimate failure. The Marshall must take all the responsibility.’ However, Victor knew that the soldiers of Ruffin’s Division, in particular the 9è léger, were capable of ‘pulling the rabbit out of the hat’ when called upon. The bloody events of the 28th July proved that Victor was right in suspecting that his men would be slaughtered in broad daylight climbing that hill. If he had delayed Ruffin’s attack until the morning it would probably have been better co-ordinated but so would have been the defence. Sources[Thanks to Ron Greatorex for the British accounts]

Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #56 Back to First Empire List of Issues Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List © Copyright 2001 by First Empire. This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com |

The Battle of Talavera [27-28 July 1809] was rated as one of the bloodiest of the Peninsular battles. General Wellesley had drawn his combined British and Spanish force [55,000 men and 60 guns] in a two mile line west of the Alberche River, stretching from Talavera northwards to the Cerro de Medellin hill, which anchored his left flank. Coming from the east were Joseph Bonaparte (King of Spain) and Marshal Jourdan with two Corps [46,150 men and 80 guns]. The battle saw the failure of the French to dislodge Wellesley’s army [suffering over 7000 casualties in the process] in a series of bloody frontal attacks against prepared defences behind the Portiña Ravine. That evening, the French retreated from the field but, as Soult was marching down from the north with another French army, Wellesley was also forced to retreat, to avoid being cut off from Portugal.

The Battle of Talavera [27-28 July 1809] was rated as one of the bloodiest of the Peninsular battles. General Wellesley had drawn his combined British and Spanish force [55,000 men and 60 guns] in a two mile line west of the Alberche River, stretching from Talavera northwards to the Cerro de Medellin hill, which anchored his left flank. Coming from the east were Joseph Bonaparte (King of Spain) and Marshal Jourdan with two Corps [46,150 men and 80 guns]. The battle saw the failure of the French to dislodge Wellesley’s army [suffering over 7000 casualties in the process] in a series of bloody frontal attacks against prepared defences behind the Portiña Ravine. That evening, the French retreated from the field but, as Soult was marching down from the north with another French army, Wellesley was also forced to retreat, to avoid being cut off from Portugal.

Further up the Medellin, Low’s brigade of the KGL were drawn up in a line. Although initially surprised by the 9è, they managed to loose off one telling volley before they were swept aside by the light infantrymen’s bayonets: [Girod] ‘We had already reached two-thirds up the height without meeting any enemy, when we suddenly received a terrible discharge of musketry, that in an instant caused us to suffer a heavy loss: nearly 300 men and 13 officers, among which our Colonel, my Chef de Bataillon, our two Adjudant-Majors and our two Carabinier Capitaines, in a nutshell, the principle commanders of our two columns were put hors de combat: a lone Chef de Bataillon remained to us, who commanded the second, which I was a part of; naturally, he replaced the wounded Colonel, and was himself replaced by my Captain, who was found to be the most senior in rank; Correspondingly, I took the command of my company. The loss that we felt, far from stopping our vigour, seemed to excite it again more; and, to shouts of: ‘Vive L’Empereur!’ we finished the climb up the hill.’

Further up the Medellin, Low’s brigade of the KGL were drawn up in a line. Although initially surprised by the 9è, they managed to loose off one telling volley before they were swept aside by the light infantrymen’s bayonets: [Girod] ‘We had already reached two-thirds up the height without meeting any enemy, when we suddenly received a terrible discharge of musketry, that in an instant caused us to suffer a heavy loss: nearly 300 men and 13 officers, among which our Colonel, my Chef de Bataillon, our two Adjudant-Majors and our two Carabinier Capitaines, in a nutshell, the principle commanders of our two columns were put hors de combat: a lone Chef de Bataillon remained to us, who commanded the second, which I was a part of; naturally, he replaced the wounded Colonel, and was himself replaced by my Captain, who was found to be the most senior in rank; Correspondingly, I took the command of my company. The loss that we felt, far from stopping our vigour, seemed to excite it again more; and, to shouts of: ‘Vive L’Empereur!’ we finished the climb up the hill.’

On both sides, sentries were sent out and an uneasy peace reigned: [Nicol] ‘Vedettes were placed a few yards in front, and we sat down in the ranks and watched every movement of the enemy.’ [Girod] ‘The night was very dark; I was placed with my company, which remained fifty men strong, in an advanced position on the left flank of the regiment, to scout the position on that side. After having established, in front of my position, a line of sentries twenty-five paces from each other, I permitted my men to sit on their havresacs, with their muskets between their legs. Greatly fatigued by the march, during a day of overwhelming heat; after the bath that we had taken in the river Alberche, while fording it fully dressed; we had kept our soaked clothes on our bodies; our baggage remained in the rear, I had not, for my account, even a coat to protect me from the freshness of the night. It was also impossible to make soup, first (and this reason can dispense all others) because we had neither supplies nor means to obtain ourselves any, and, in second place, because the near vicinity of the enemy did not allow us to light a fire; finally, the assault that we had delivered had left us dripping with sweat..... It was in such circumstances that we soon abandoned ourselves to the sleep which overwhelmed us.’

On both sides, sentries were sent out and an uneasy peace reigned: [Nicol] ‘Vedettes were placed a few yards in front, and we sat down in the ranks and watched every movement of the enemy.’ [Girod] ‘The night was very dark; I was placed with my company, which remained fifty men strong, in an advanced position on the left flank of the regiment, to scout the position on that side. After having established, in front of my position, a line of sentries twenty-five paces from each other, I permitted my men to sit on their havresacs, with their muskets between their legs. Greatly fatigued by the march, during a day of overwhelming heat; after the bath that we had taken in the river Alberche, while fording it fully dressed; we had kept our soaked clothes on our bodies; our baggage remained in the rear, I had not, for my account, even a coat to protect me from the freshness of the night. It was also impossible to make soup, first (and this reason can dispense all others) because we had neither supplies nor means to obtain ourselves any, and, in second place, because the near vicinity of the enemy did not allow us to light a fire; finally, the assault that we had delivered had left us dripping with sweat..... It was in such circumstances that we soon abandoned ourselves to the sleep which overwhelmed us.’