Battle of Dennewitz

Oudinot’s Revenge

By Patrick E. Wilson, UK

| |

On 2nd September 1813 Marechal Michel Ney received orders to assume commend of the French Armée of Berlin, march with it to Baruth, arriving there by the 6th September. By which time Napoleon hoped to be at Luckau with Marechal Auguste Marmont’s Corps to support him, then Ney was to march on Berlin itself, attacking and capturing it by the 10th September. Ney’s orders were straightforward and should have lead to the full of Berlin that September.

But Ney was scarcely any better then Oudinot at independent commend, the Battle of Bautzen that spring had clearly demonstrated this when Ney’s commend had failed to carry out its task (as it was envisaged by Napoleon) and had got itself sucked into the fighting around the Kreckwitz heights. Nevertheless Ney received command of the Armée of Berlin to the great annoyance of Oudinot, who felt he had been unfairly treated and subsequently was not the least inclined to work willingly with Ney. Indeed it was known that Oudinot personally hated Ney, as they shared many similar characteristics, including an obstinacy and bullheadedness that could easily lend to command difficulties. A better choice would have been to replace Oudinot with Marechal Auguste Marmont whilst at the same time giving Oudinot Marmont’s Corps, thus removing Oudinot from the Armée of Berlin and making use of Oudinot’s fighting qualities in command of a Corps under Napoleon’s immediate eye. Marmont had much experience of independent commend and could be relied upon not to do anything too stupid, indeed he had come very close to defeating the Duke of Wellington in the Peninsula, (a single mistake had lead to his famous defeat at Salamanca).

If Ney’s appointment was questionable and Oudinot’s presence a recipe for disaster then perhaps we ought to take a brief look at the other Corps commanders of the Armée of Berlin before we proceed any further with this essay, as they too would have a part to play at Dennewitz. The first of them, General Comte Henri Bertrand, the commander of 4th Corps d’Armée, was a former Imperial aide-de-camp, a renowned engineer who had bridged the Danube in the 1809 campaign and had been the Governor of Dalmatia from 1810 to 1813. Now he commanded a French Corps d’Armée. He had no experience of such a command; he had failed to intervene effectively at the Battle of Lutzen, got himself surprised at Konigswartha prior to the Battle of Bautzen.

At that battle he was under the supervision of the redoubtable Marechal Jean de Dieu Soult and had done well but at the engagement of Blankenwalde that August he had been easily driven back by the Prussian General Tauentzien. So far then Bertrand had hardly distinguished himself, he was a good engineer as the 1809 campaign had shown, and his governor-ship of Dalmatia had improved on Marmont’s previous efforts. But Bertrand, as we shall see, was not to distinguish himself at Dennewitz. His senior divisional commander, General Comte Charles Morand, one of Marechal Louis Davout’s famous triumvirate, would have been a much better choice. He had lots of experience at divisional level, was an ambitious and capable commander, and it is hard to see him failing as Bertrand did. Indeed, he later replaced Bertrand as commander of 4th Corps and held Mayence with that Corps throughout the 1814 campaign.

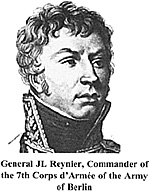

It is strange that Reynier was never given a Marechal’s baton, he undoubtedly deserved one. He commanded his Corps well in 1813, particularly at Dennewitz but others, as we shall see, ruined his efforts.

The third of Ney’s Corps commanders we have already met, Marechal Nicolas Oudinot, the commander of the 12th Corps d’Armée, he had much experience, frequently wounded, famous for commanding the Grenadier division of 1805-07, he had replaced Marechal Jean Lannes in 1809 when that Marechal had been killed and had been very lucky not to be court-martialled for his unauthorised attack on the second day of the Battle of Wagram. In Russia he held an independent command but again his luck had held, General Gouvion Saint-Cyr saving him from defeat at Polotsk and a musket ball in the stomach at the Crossing of the Berezina not proving fatal! His performance in the spring campaign of 1813 was hardly spectacular; his advance on Berlin that autumn was ill advised and led to defeat at Gross Beeren. Like Bertrand, Oudinot had an officer in his Corps that could have commanded better, and would certainly have co-operated with others better. This officer, General Comte Armand Guilleminot, was like Reynier a staff officer with good combat experience. Guilleminot had served under such diverse characters as Jean Baptiste Bessieres, Jean de Dieu Soult, Etienne Jacques MacDonald and Eugene du Beauharnais. His combat experience had been during the Russian retreat, where he had lead the 13th division after General Delzons had been killed at the Battle of Malojaroslavets. In July 1813 he had replaced General Lorencez as commander of Oudinot’s 14th division. His efforts to support Reynier at Dennewitz would be undermined by his superior Oudinot but more of that later.

Having had a brief look at the senior commanders of the Armée of Berlin, let us take this opportunity also to comment upon the various components of that Armée.

General Bertrand’s 4th Corps consisted of General Morand’s 12th French division, this was formed of French Infantry Regiments that had grown ‘soft’ in Italy but under Morand’s leadership they proved solid enough. Bertrand’s next division, the 15th Italian division under General Peyri, later General Fontanelli, is perhaps best remembered for its near destruction by Russian cavalry at Konigswartha. It was formed of Italian conscripts and was much diminished by the time of Dennewitz. However, the German State of Württemberg provided Bertrand’s last division and his cavalry reserve. The 38th division had started the campaign of 1813 with 8 excellent battalions of Württemberg Infantry but the campaign had taken its toll, the division had been heavily engaged at the Battle of Bautzen, and they were reduced to three combined battalions when they were called upon to fight at Dennewitz. It was these troops together with their cavalry that provided Bertrand with perhaps his best troops, who not only did their duty well but like their colleagues had done in Russia were amongst the last troops of the confederation to desert Napoleon. Bertrand’s Corps was a rather multinational affair.

General Reynier’s 7th Corps was somewhat better, his first two divisions, the 24th and 25th divisions, were formed from Saxon troops, as was the cavalry of his Corps. These troops were mostly conscripts, though some were survivors from the Russian campaign but they had taken little part in the spring campaign in Germany. Instead their Generals had attempted to hold them back so that they could be deployed on the Allied side that autumn but events had overtaken their hopes and consequently they found themselves on the French side again. Reynier then led them effectively at the Battles of Gross Beeren and Dennewitz, where they seemed to bear the brunt of the fighting and suffered accordingly. At Leipzig they finally defected and who can blame them! Reynier’s third division, the 32nd division under General Baron Pierre Durutte, an excellent divisional commander, was composed of French penal Infantry Regiments and though desertion was a difficulty with such material Durutte managed to maintain them as an effective part of Reynier’s Corps. Indeed, Durutte commanded the 32nd division with distinction from 1812 to 1814.

Marechal Oudinot’s 12th Corps was formed of two French divisions, 13th and 14th divisions French Infantry Regiments that had served in Italy and a couple of cohort regiments (formerly National Guard but formed into new line Regiments by Napoleon in early 1813). These troops were similar to those commanded by Morand and like those, that when commanded by good divisional commanders they proved steady enough. Oudinot’s third division, the 29th (Bavarian) division, consisted of 8,000 unenthusiastic Bavarians, who had little motivation in this campaign. Indeed their government was involved in behind the scenes talks with the Austrians throughout the autumn campaign of 1813. The Bavarians had fought well enough at Bautzen, missed the Battle of Gross Beeren and arrived too late to be of any use at the Battle of Dennewitz.

Napoleon suspected them of ill will and was proved correct when they declared for the Allies at the time of the Battle of Leipzig. Oudinot’s cavalry also consisted of these unenthusiastic Bavarians.

Finally we have the 3rd Cavalry Corps commanded by Napoleon’s cousin General Arrighi, Duc du Padua; he had the light cavalry division of General Lorge and the Heavy cavalry division of General Defrance. These divisions were formed of single squadrons grouped together to form brigades for combat purposes, General Defrance in particular was to perform well at Battle of Dennewitz with his Heavy cavalry. By all accounts Arrighi de Casanova, to give him his full name, was a very experienced officer who performed well in this campaign. He had served in Egypt and Italy, commanded a Cuirassier division in 1809 (actually he took over General Espagne’s division when that excellent officer had been killed at the Battle of Aspern-Essling). Sadly we do not hear much of him at Dennewitz, which leads one to suspect that he may have already taken up his post of Governor of Leipzig, where he later fought to keep open the road to the Rhine.

His light infantry training and experience undoubtedly contributing to this, though it seems he had no time for Scharnhorst or his ideas. The Battle of Dennewitz was to be the most famous of his victories. His Colleague, General Boleses Friederich von Tauentzien was 52 years old and the victor of Blankenwalde; he fought well in the Jena campaign of 1806 at Schliez and Jena itself. Indeed he was one of few senior commanders from that period to be re-employed in 1813. After the Battle of Dennewitz he was to gain fame for his capture of Wittenberg during the winter of 1813-14.

The two Corps d’Armée commanded by these two officers were the 3rd and 4th Prussian Corps d’Armée. The 3rd Corps d’Armée had the usual mix of Regular, Reserve and Militia regiments, two of its brigades were of East Prussian regiments, and two were of Pomeranian regiments. The Corps cavalry consisted of a Dragoon and a Militia Brigade. The Corps Artillery Reserve had the usual amount of 12pdr cannon but was also reinforced by 2 Russian 12pdr position batteries and a Russian Hussar Regiment. It was these brigades that would win renown at the Battle of Dennewitz.

The 4th Corps d’Armée differed from the 3rd Corps d’Armée in that its brigades were formed of Reserve and Militia Regiments only. Two of its brigades, those of General von Dobschuetz and Colonel von Lindenau, were within supporting distance of the 3rd Corps d’Armée and under von Tauentzien’s immediate commend. The other two brigades were detached; one under General Hirschfeldt was observing General Baron Girard at Magdeburg and had defeated that in August at Hagelberg. The other under General von Webeser was before Torgau. There was no reserve cavalry with these brigades as each had a regiment or two attached as part of the brigade.

Both Corps, though containing an element of experienced soldiers, especially the 3rd Corps d’Armée, were mostly inexperienced recruits and Militia but what they lacked in experience they more then made up for in enthusiasm, as they were fighting for their very homes.

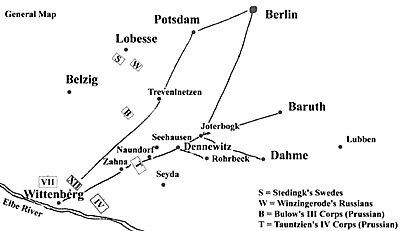

Marechal Ney assumed command of the Armée of Berlin on 3rd September; the Armée was then north of Wittenberg, where they had retired following the defeat at the Battle of Gross Beeren. Ney did not issue his orders until the 5th September. These directed Oudinot’s Corps followed by Bertrand’s to march upon Zahna and Juterbogk. Reynier’s Corps was to march first though, then turn right toward Baruth acting as a flank Guard to Oudinot and Bertrand as well as threatening the right of any enemy at Zahna. Directly opposite Oudinot’s line of march lay General von Tauentzien at Zahna, to that General’s right lay General von Bulow’s Corps and to Bulow’s right lay the Russians and Swedes of the Armée of the North. The Allied tan was simple. Tauentzien was to act as an Advance guard and lure the Armée of Berlin to Dennewitz, where he would give battle knowing that von Bulow would be available to attack the enemy left and that the Russians and Swedes should also arrive to take the enemy in rear totally enveloping the Armée of Berlin. Oudinot duly engaged Tauentzien at Zahna and drove him back upon Dennewitz after a severe fight, though in part Tauentzien drew back because he saw Reynier’s advance to the south of him.

That night Oudinot’s Corps bivouacked in front of Sayda, Reynier now occupied Zahna and Bertrand was to the north of Reynier at Seehausen and Naundorf. The same night found Tauentzien at Dennewitz; von Bulow though marched through the night so that he would be available to support Tauentzien next morning. The Russians and Swedes, under the Crown Prince of Sweden, (formerly Marechal Jean Baptiste Jules Bernadotte) were 15 miles away and within supporting distance.

Ney’s plan for the 6th September was to use Bertrand as a flank guard by marching him to Juterbogk, whilst Oudinot marched from his positions towards Dahme and Luckau, where Ney expected another Corps to join him for the advance on Berlin. This Corps Napoleon had been unable to send because at moment he had to deal with another advance by General von Blucher’s Armée of Silesia. Finally, Reynier had been ordered to march on Rohrbeck via Oehna, where Oudinot was supposed to wait until he passed before proceeding to Dahme. This instruction was to have unexpected consequences, as Reynier did not pass Oudinot because he did not use the road to Oehna but instead chose to use the road that led to Dennewitz. Oudinot would wait four hours for Reynier to pass him!

The battlefield of Dennewitz is basically a sandy plain with woods and low knolls (which made ideal artillery positions) scattered about the place. The major feature of the area is the Agerbach stream, which flows in a deep channel and passes through the key villages of Nieder Göhlsdorf, Dennewitz and Ruhrbeck. The area is typical of that region of Germany and on 6th September 1813, it was not only a hot day but also a strong north-westerly wind drove clouds of sand everywhere.

Bertrand started his march for Juterbogk at 8.00am, at 11.00am he had reached Dennewitz and saw von Tauentzien’s two brigades drawn up for battle on the knolls to the north of that village. Bertrand immediately launched his Corps into battle, though he had no orders to fight a battle that day and it is known that Ney did not desire one that day either. [3]

Bertrand’s leading division under General Fontanelli at once deployed beyond the Agerbach stream and pushed back von Tauentzien’s enthusiastic militiamen gaining the necessary space for the rest of Bertrand’s Corps to deploy. General Morand’s division deployed to Fontanelli’s left and together they advanced and almost overwhelmed von Tauentzien’s by now wavering militiamen but a charge by militia cavalrymen saved the day.

By now von Bulow was putting in an appearance on von Tauentzien’s right wing, resuming his march at 10.30am, von Bulow’s leading brigade was able to attack Morand two hours later. This brigade, von Thuemen’s, was easily repulsed by the intrepid Morand but then Hessen-Homburg's brigade arrived to support von Thuemen and Morand was forced to retire to a new position. This position was just north of the Agerbach stream, Morand still held Bertrand’s left around a knoll with a windmill on it near Nieder Göhlsdorf. Fontanelli’s Italians held still held the centre of this line whilst Franquemont’s Württembergers held the right, which rested on a wood to the northeast of Nieder Göhlsdorf and to the north of Rohrbeck. It was here that von Thuemen and von Tauentzien renewed their attacks, the Württembergers resisted with great vigour and were supported by General Kruckowiekils Polish cavalry brigade who engaged the Prussian Lieb Hussars. But the Württembergers were not strong enough to hold their position and were driven from the woods they defended towards Rohrbeck losing many prisoners to the triumphant Prussians. It was around 2.00pm and Bertrand was now defeated if no help was forthcoming.

Fortunately Reynier chose this moment to put in an appearance, as did Marechal Ney himself, who was not pleased with what he saw. However he ordered General Durutte’s division to support Bertrand as quickly as possible and sent Reynier’s Saxon cavalry over to Rohrbeck to cover Bertrand’s now exposed right and take some of the pressure off the Württembergers. Meanwhile Reynier seeing that the Prussians were approaching from the west of Nieder Göhlsdorf, drew up his Saxon Infantry divisions opposite the village of Göhlsdorf and positioned General Defrance’s Heavy cavalry division on his right to the south of Nieder Göhlsdorf. At 3.00pm Durutte, who had now joined up with Morand on Bertrand’s left, now attacked and took Nieder Göhlsdorf from Colonel von Clausewitz’s 4th East Prussian Infantry Regiment and von Thuemen was again compelled to fall back. At the same time Reynier had ordered his Saxons forward and had encountered Hessen-Homburg's brigade in the village of Göhlsdorf and a vicious fight had ensured, that saw first the Saxon then the Prussian gain the upper hand as each side threw in more troops. General von Bulow soon had to reinforce Hessen-Homburg with von Krafft’s brigade as Reynier gradually committed both of his Saxon divisions to the fight for Göhlsdorf. But it was Reynier who now felt that the odds were starting to go in favour of the Prussians and had sent a note to Oudinot to ask him to hurry his march. Oudinot only began to arrive with his Corps as the Saxons were beginning to tire but reassured of support Reynier attacked again with renewed vigour and drove the Prussians almost out of Göhlsdorf altogether. General von Bulow was forced to commit his final reserve, General von Borstell’s brigade, to the combat.

Elsewhere, von Thuemen and von Tauentzien were maintaining the pressure on Bertrand and Durutte; not only retaking Nieder Göhlsdorf but Dennewitz too and even seeking to turn Bertrand’s right at Ruhrback. Still with Ney’s inspired leadership Bertrand’s troops were holding out - just! Indeed the seriousness of the fighting seems to have convinced Ney that the issue of the battle would be decided in this area of the field. This was not the case. The issue would be decided around Göhlsdorf and it was here that the battle was about to be decided by the decisions of a newcomer to the fray, Marechal Oudinot.

Von Bulow’s position around Göhlsdorf was one of great danger, his troops were tired by long hours of marching and fighting, only von Borstell’s brigade was relatively untouched but he was gradually being drawn into the fighting against Reynier’s gallant Saxons. He could see the arrival of Oudinot’s Corps beyond Reynier’s Saxons, in fact Oudinot had already positioned a strong battery of artillery on Reynier’s left and this was soon inflicting severe damage on his forces. If Oudinot now joined Reynier and attacked him around the Göhlsdorf area, as seemed likely, then he would be overwhelmed before the Russians and Swedes under the Crown Prince of Sweden could put in an appearance.

He was then somewhat astonished to observe that Oudinot was moving off toward Rohrbeck.

Reynier, like his opponent, expected Oudinot to support him in gaining the victory that his Saxons had undoubtedly gained in the fighting around Göhlsdorf. So we can imagine his despair when Oudinot received a note from Ney ordering him to march to the right to support Bertrand. Oudinot like Reynier could see clearly that the battle would be decided at Göhlsdorf but he said that he was duty bound to obey, as Ney was his commander. It seems that Oudinot still resented his supersession by Ney as the Armée of Berlin’s commander and would not listen to Reynier nor General Guilleminot, one of his own divisional commanders, as they pleaded with him to leave at least one division to help Reynier complete his victory. This obstinacy to obey the letter of his orders was in complete contrast to an episode in Oudinot’s earlier career at the Battle of Wagram, when he had attacked on the 2nd day of that great battle whilst having specific orders not to do so.

General von Bulow, no doubt not believing his luck, took immediate advantage of the situation and launched von Borstell’s brigade into Göhlsdorf and through the Saxons fought back furiously, aided by Guilleminot’s 156th Regiment of the ligne which had stopped to assist as the rest of Oudinot’s Corps marched off to aid Bertrand. The Saxons found themselves driven from the village with the loss of many men and would have been annihilated but for a timely charge by General Defrance’s Heavy cavalry division. But in the resulting confusion Reynier’s Saxons carried away Guilleminot’s division as well, despite Reynier’s frantic efforts to rally his men.

Meanwhile before Oudinot’s men could reach Bertrand his Corps had lost control of Rohrbeck and was already falling back when Oudinot’s Corps, though hardly engaged at all, found themselves either swept away in Reynier’s rout or retreating with Bertrand as he left the field of battle. Oudinot’s decision to follow his orders literally had cost the French the Battle, though Ney’s decision to plunge sword in hand into the fighting on Bertrand’s front rather then remaining detached and controlling the battle is also open to censure.

Bertrand retreated about 6.00pm for Dahme, together with Oudinot’s Bavarian division that had not fired a shot in anger. Here Ney himself continued the retreat to Torgau.

Where both Oudinot and Reynier had retreated with their disorganised Corps. The Armée of Berlin was shattered, with losses of at least 22,000 men, including 13,000 captured. Both the Saxons and Württembergers had lost heavily in the fighting; the Württembergers losing over 2,000 men in killed, wounded and captured. Oudinot’s corps was broken up, the 13th and 14th divisions being combined into one, the Bavarians sent off to more mundane duties such as guarding the lines of communications from the incessant Cossack attacks. Reynier’s Saxon divisions were combined into one and he was given the 13th division (now combined with 14th) to help replace his losses. Bertrand’s Corps was shattered; his Württembergers were reduced to brigade strength, as were his Italians. Only Morand’s division retained much of its previous strength and could termed a ‘division’. The Battle of Dennewitz was a disaster for the French Armée of Berlin and although it was reinforced by the arrival of Marmont’s 6th Corps d’Armée, it never really threatened Berlin again. Dennewitz was for the Prussian Army a memorable victory, gained after a very heavy fight and one that they thoroughly deserved to win having lost, according to Petre, 10,500 men between 5th and 10th September. General von Bulow would receive the title Count of Dennewitz at the end of the war for this victory.

Though the Prussians undoubtedly deserved victory, the French commanders made a major contribution to this.

Firstly, Bertrand had practically thrown himself into a battle that his commander-in-chief did not desire; though it is true his troops almost fought themselves out of the cul-de-sac Bertrand had got them into.

Secondly, Ney, when he arrived, almost immediately plunged himself into the fighting line like a lieutenant of the Grenadiers rather then acting like the commander-in-chief he was but then that was Ney, a soldier by example. Sadly he no longer had as his chief-of-staff General Henri Jomini to advise him as he had had in the past, that soldier after an argument with Marechal Alexandre Berthier had gone over to the enemy and was now advising the Tsar.

But perhaps more significantly, we have Oudinot who was more than a little upset by being replaced by a chap he had no time for at all. Oudinot’s actions were really inexcusable, especially when he was opposed by two skilled officers, Reynier and Guilleminot, and in light of his own record in regard to the obeyance of orders. He should have attempted to inform Ney of the true situation or at least left Reynier with the means to secure his hard won victory that was clearly in sight. Instead, Oudinot let his view of the situation be clouded by his own vindictiveness. Napoleon was right when he once said that he should not have made either Marmont or Oudinot a marshal, as he needed to win a war. [4]

In Oudinot’s case this was true, when given independent commands he almost invariably failed if he was not accompanied by someone who was superior to him in military skill. Both 1813 and 1814 demonstrate this, in 1812 he was ably supported by Gouvion Saint-Cyr. Perhaps Oudinot should have been retained at the head of the Grenadiers where he undoubtedly belonged.

[1] Petre, F.L., Napoleon’s last Campaign In Germany 1813 (London: Arms & Armour Press, 1974 Reprint of 1912 edition).,p.269.

Battle of Dennwitz Order of Battle

|

Unfortunately, the previous commander of the Armée of Berlin, Marechal Nicolas Oudinot, was still with the army. He had been replaced because of his defeat at Gross Beeren on 23rd August 1813, when he had advanced on a dispersed front then rainy afternoon and had been driven back by the Prussians. He was greatly censored by Napoleon for this: “It is really difficult to have less heed then the Duke of Reggio”. [1]

Unfortunately, the previous commander of the Armée of Berlin, Marechal Nicolas Oudinot, was still with the army. He had been replaced because of his defeat at Gross Beeren on 23rd August 1813, when he had advanced on a dispersed front then rainy afternoon and had been driven back by the Prussians. He was greatly censored by Napoleon for this: “It is really difficult to have less heed then the Duke of Reggio”. [1]

The second of Ney’s Corps commanders, General Jean Louis Reynier, the commander of the 7th Corps d’Armée, was perhaps the best of them all. He had plenty of experience but excelled at planning and staff work, though he had commanded a Corps well in both Spain and Russia. Apparently he commanded German troops better then French, which probably accounts for his success in commanding the Saxons in Russia and Germany. Napoleon himself said: “Reynier was a man of talent, but better fitted to plan the operations of an army of 20,000 to 30,000 men, then to commend one of 5,000 to 6,000.” [2]

The second of Ney’s Corps commanders, General Jean Louis Reynier, the commander of the 7th Corps d’Armée, was perhaps the best of them all. He had plenty of experience but excelled at planning and staff work, though he had commanded a Corps well in both Spain and Russia. Apparently he commanded German troops better then French, which probably accounts for his success in commanding the Saxons in Russia and Germany. Napoleon himself said: “Reynier was a man of talent, but better fitted to plan the operations of an army of 20,000 to 30,000 men, then to commend one of 5,000 to 6,000.” [2]

Having considered the commanders and make up of the Armée of Berlin, it is now appropriate that we consider their opponents the Prussians under Generals von Bulow and von Tauentzien. As it was to be these two commanders and their troops more then their Russian and Swedish allies, who fought and won the Battle of Dennewitz and to them all the glory should be given. The principle commander was General Friederich Wilhelm von Bulow, then 58 years old and the victor of Gross Beeren. He had served in 1806-07 campaign in Poland commanding light infantry under the gallant General Anton Wilhelm von L’Estocq. He was a product of the military institutions of Frederick the Greet, deriving his view of war from the lessons of Seven Years War but seemed to grasp the nature of Napoleonic warfare.

Having considered the commanders and make up of the Armée of Berlin, it is now appropriate that we consider their opponents the Prussians under Generals von Bulow and von Tauentzien. As it was to be these two commanders and their troops more then their Russian and Swedish allies, who fought and won the Battle of Dennewitz and to them all the glory should be given. The principle commander was General Friederich Wilhelm von Bulow, then 58 years old and the victor of Gross Beeren. He had served in 1806-07 campaign in Poland commanding light infantry under the gallant General Anton Wilhelm von L’Estocq. He was a product of the military institutions of Frederick the Greet, deriving his view of war from the lessons of Seven Years War but seemed to grasp the nature of Napoleonic warfare.