Towing The Line

The Evolution Of England's

Naval Officers (1653-1805)

Part 1

by Chris Dorsey, USA

| |

The most distinguishing characteristic of naval combat of the time was the line ahead formation. England first used this tactic in the battle of Gabbard in 1653, during the first Dutch War. The idea was to bring ones ships into a line, each in the other's wake or grain, and engage the enemy with broadsides. The formation was first introduced into fighting instructions issued to a fleet in the same year. This was seen in the Duke of Portland's Commonwealth Orders.

Ins. 7th. In case the admiral should have the wind of the Enemy, and that other ships of the fleet are to windward of the admiral, then upon hoisting up a blue flag at the mizen yard or the mizen topmast, every such ship then is to bear up into his wake, and grain upon severest punishment The words 'severest punishment' placed an importance on strict adherence to the formation and necessity to maintain the line. This interpretation stagnated tactics and proved the downfall of more than one admiral. Julian Corbett made the argument the letter of the instructions called for this strict adherence. Other authors, such as John Creswell believed that although this was implicit, there were allowances for admirals to make tactical decisions, make additional instructions or set the whole set of instructions aside locally.

England had many opportunities to test their instructions during the second and third Dutch Wars. The Admiralty learned valuable lessons during this period. The Dutch Wars were not only marked by aggressive admirals such as Monke and Rupert, but by exceptional organization at the highest levels by Samuel Pepys. He worked tirelessly to ensure the competence of his sea officers. By instituting examinations for lieutenants and ensuring chaplains and surgeons were assigned onboard ships, he laid the foundation for the future success of the Royal Navy.

Naval Leadership

The naval leadership of the time was separated into two schools on the matter of how to engage the enemy. The Duke of York and Penn believed in the necessity of formality during battle and maintaining the line at all costs. The Duke of York, in his instructions, forbade breaking the enemy's line unless his own line could outstretch the foe or if necessary to save a ship from being pressed to a lee shore. Rupert and Monke stressed aggressive, decisive action and concentration of fire upon a smaller part of an enemy fleet. Monke won this conflict when he relieved the Duke of York. His theories were tested during the Four Days battle against the capable Dutch Admiral de Ruyter. The English were heavily outnumbered. One hundred Dutch ships faced fifty- nine English sail of the line. Monke saw a weakness in the Dutch line and attacked. He managed to isolate the Dutch van and caused considerable damage. However, he was outnumbered and vulnerable to being doubled. The losses on both sides were heavy. The States lost 3 Vice-Admirals, 4 ships and 2,000 men while the English lost 8,000 and 17 ships. Monke came out worse than de Ruyter but his fleet had performed well against a much larger force. The French observer De Guiche made this statement in regard to English seamanship: "Nothing equals the beautiful order of the English at sea…" 6

The end result was a swing toward conservative action. This was aided by Penn's recollection of the battle with Pepys (who disliked Monke). The outcome of this meeting was Pepys' remedy for the 'problems' that occurred:

2. We must not desert ships of our own in distress, as we did, for that makes a captain desperate, and he will fling away his ship when there are no hopes left him of succour.

3. That ships when they are a little shattered must not take the liberty of to come in of themselves, but refit themselves the best they can and stay out. The first permanent Fighting Instructions were issued in 1691. These instructions were used at the battle of Toulon and set the stage for the sad story of Admiral Byng. An engagement occurred prior to Byng's case that is worth notice not due to its outcome, but for a comparison of tactical styles. The battle of Malaga took place on August 13, The battle itself was a draw with no ships on either side being lost. The casualties for this action were very high on the allied side. English losses were 2368 killed and wounded while the Dutch lost 360 for a total of 2728 for 51 allied ships engaged. 8 These losses when compared to Nelson's casualties for the battle of the Nile, are interesting. Nelson reports a total of 895 casualties for 14 vessels. 9

This made the casualty rate per vessel almost equal. Nelson virtually destroyed the French fleet, however. The difference between the battles of Rodney, Jervis and Nelson (which will be discussed later), and those in the early 1700's was the lack of flexibility and aggressiveness that allowed for conclusive engagements. The thought of obeying the instructions to the letter prevailed during this time and led to many such indecisive battles. Those who chose to challenge the institution and did not meet with success on the seas paid the price. A perfect example was Admiral Matthews at Toulon.

Court Martial

The major outcome of this battle was the court-martial of the English admiral and the effect it had on a certain member of the jury. The battle itself had the English facing the Spanish and French fleets. Matthews did not keep his formation during the battle. This was not helped by his second in command, Admiral Lestock, (who was insulted by Matthews the previous day). Lestock seemed sluggish and did not keep the rear of the force up with the rest of the fleet. Matthews' signal for a line abreast further distanced the two and eventually they met the enemy fleet in uneven numbers. Matthews, fearing the larger enemy line would double him, left his line to engage the Spanish flagship. The result was once again indecisive but Matthews was cashiered for his inability to maintain formation and "attacking with unequal distribution of force contrary to discipline." 10

Admiral Byng sat on Matthews' court-martial and it had a dramatic effect on naval history. The problem with the fighting instructions was that they were both a necessity and a hindrance for admirals of the time. Creswell explained the dilemma: Rooke's instructions remained, as they had a right to remain, the pattern on which tactics were to be based when practicable, but there was no question of their imposing an unjustified rigidity on an admiral whose appraisal of a situation saw that more flexibility was called for. 11

Mathew's fate was still in Byng's thoughts during the battle of Minorca on May 20th, 1756. Byng's mishandling of the fleet placed his force diagonal instead of parallel to the enemy. He ordered engagement, bringing the van of his line into action much earlier than the rest. The van did not properly form and ran head-on into the French line. The English van was severely pressed, the sixth ship in line being forced back onto the rear. Byng's flag captain recommended that he leave the line to assist his ships in the van. Byng's reply, which highlighted the problem of this period was that, "Mr. Mathews misfortune to be prejudiced by not carrying his force together, which I shall endeavor to avoid." 12 The battle itself was inconclusive, but Byng failed to support Fort Mahon, which fell to the French forces.

The lack of a positive outcome, the fall of Fort Mahon and questions of Byng's handling of the fleet, led to his court-martial. The jury cleared Byng on claims of cowardice but little else went in his favour. A witness at the hearing, Captain Amhurst, summed up the overall opinion when he stated, "I can not pretend to speak positively of the Admirals conduct during the Engagement." 13

There was little doubt of Byng's fate. The court issued the following findings and Opinions:

Should have landed some troops from his frigates to support the British fort. Should have handled the fleet to properly align it for battle. Not made the signal for battle when he did. Was responsible for the division of his fleet. Fired early, wasting shot obscuring view. Should have tried to support Minorca. 14 The courts opinions:

33. Admiral Byng did not do his Utmost to relieve St. Philip's Castle, in the Island of Minorca, then besieged by the forces of the French King.

34. During the engagement between His Majesty's fleet under his command, and the Fleet of the French King, on the 20th of may last; did not do his Utmost to take, seize and destroy, the Ships of the French King, which it was his Duty to have assisted. Guilty of Article 12 of Articles of War. - or shall not do his utmost to take or destroy every Ship which it shall be his Duty to engage; and to assist and relieve all and every of His Majesty's Ships which it shall be his Duty to assist and relieve." The execution of Admiral Byng marked another pendulum swing in the philosophy of English naval authorities. This change was clearly seen in Admiral Hawke's instructions of the same year as Minorca:

The stage was set for a 'revolution' in naval tactics. Hawke's victory at Quiberon Bay and Rodney's success against de Guichen at the Saints led the way for innovators such as Jervis and Nelson to finally give England unquestioned dominance of the seas. Rodney's influence aided officers in breaking through the letter of the law that was the Fighting Instructions, in order to realize its forgotten intent. 17

Despite being foiled in his attempt for close action, Rodney's skill was not lost on de Guichen. He later informed Rodney that had his instructions been followed he would have been his prisoner. 19

The fundamental obstacle of the British was displayed in this battle as in almost every other action with France. English admirals tried continually to draw their enemies to action, but the French were of the mind to stand off and fire at the English rigging to ensure they could make their escape if the going got too rough.

Many naval leaders of the time studied this problem and began to piece together the use of breaking the enemy's line to take the leeward from them and force action. Rodney finally succeeded in 1782 and although the main body of the enemy escaped, individual groups were isolated. This maneuver was incorporated into Hood's instructions and given a corresponding signal, 20 : "Signal 235. When fetching up with the enemy to leeward, and on the contrary tack, to break through their line and endeavor to cut off part of the van or rear". 21

Rodney's greatest success came at the battle of the Saints in 1782. There were questions of whether his success was due to a 'lucky' shift in wind or tactical skill. The occurrence of the wind was not the issue. The ability to rapidly adapt to changing conditions is a key element of leadership and Rodney performed well regardless of the catalyst. Rodney, making full use of the change in wind, split the line in three places. This effectively 'broke the line' at two points. The ships delivered devastating fire into the enemy vessels as they passed through in succession. The remaining French ships did not engage, allowing the capture of the trapped vessels. When the Ville de Paris struck its colors with de Grasse onboard, it was the first time a French commander-in-chief had been captured. 22 Admiral Hood, who served under Rodney, was not satisfied with the victory because most of the enemy escaped. He believed that the enemy was in a state of moral and physical shock and that Rodney should have pressed the French further. 23

Mahan questioned whether other factors played a role in the defeat of the French. He mentions the better rate of fire of the English, better individual leadership and the French forming their line late as possible elements. All of these items still pointed to the key to English success in general. No matter how it happened, the enemy was placed in the 'utmost confusion', and on this fact Mahan conceded: "Every principle upon which a line-of-battle constituted, for mutual support and for clear field of fire for each ship, was thus overthrown for the French and preserved for the English divisions which filed through." 25 Flexibility, professional and well-trained crews, and the desire to bring the battle to the foe were the characteristics that allowed for more decisive engagements.

|

The professionalism, flexibility and ingenuity of England's sea officers during the 17th and 18th centuries protected and extended English interests and enforced her policies across the globe. The age of sail was a period of great adventures and challenges. A New World had been discovered, advances in navigation enhanced sea trade, and the emerging nation states realized the advantages in creating and maintaining strong trade routes. The European race for world dominance had begun and sea power was the key. England emerged as the master of the seas. A major factor in England's success was the ability of the English admirals to eventually break from strict adherence to the fighting instructions and rely on more independent, inspired action of individual commanders.

The professionalism, flexibility and ingenuity of England's sea officers during the 17th and 18th centuries protected and extended English interests and enforced her policies across the globe. The age of sail was a period of great adventures and challenges. A New World had been discovered, advances in navigation enhanced sea trade, and the emerging nation states realized the advantages in creating and maintaining strong trade routes. The European race for world dominance had begun and sea power was the key. England emerged as the master of the seas. A major factor in England's success was the ability of the English admirals to eventually break from strict adherence to the fighting instructions and rely on more independent, inspired action of individual commanders.

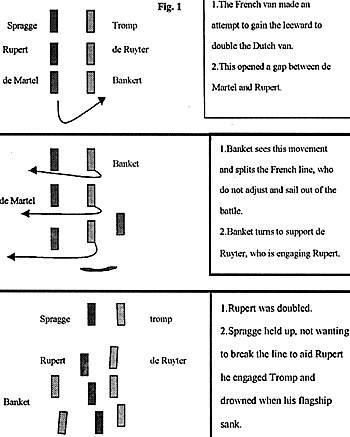

The Four Days was the first of a series of setbacks for the English. The next was the battle of Texel in August of 1673. The combined French and English fleet was fought to a draw by the Dutch, but was outmaneuvered and failed to keep the Dutch fleet inside its blockade. De Ruyter's fleet managed to effectively pass through the allied line and double their enemy as seen in Fig.1. (Mahan Pl. IV.)

England's alliances changed during the War of League of Augsburg but not her fortunes. The combined Dutch and British fleet was engaged by a French fleet under Admiral Tourville. The allies could not maintain their line during the battle and were doubled in the van by the French. A calm saved the combined fleet from further loss. The French failed to pursue as the allies retired. Although the French had won the battle they lacked the aggressive nature to follow through and complete the victory.

The Four Days was the first of a series of setbacks for the English. The next was the battle of Texel in August of 1673. The combined French and English fleet was fought to a draw by the Dutch, but was outmaneuvered and failed to keep the Dutch fleet inside its blockade. De Ruyter's fleet managed to effectively pass through the allied line and double their enemy as seen in Fig.1. (Mahan Pl. IV.)

England's alliances changed during the War of League of Augsburg but not her fortunes. The combined Dutch and British fleet was engaged by a French fleet under Admiral Tourville. The allies could not maintain their line during the battle and were doubled in the van by the French. A calm saved the combined fleet from further loss. The French failed to pursue as the allies retired. Although the French had won the battle they lacked the aggressive nature to follow through and complete the victory.

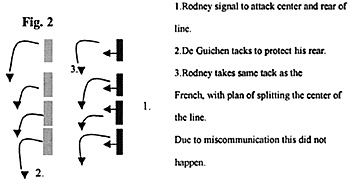

Rodney, like Monke and Rupert, believed that the only victory was complete victory. His idea was that control of specific areas of interest was not the only goal of a battle fleet. The main objective was the destruction of the enemy's fleet. Rodney's first attempt was on April 17, 1780, near Martinique. It is set out in the following illustration Fig 2. 18

Rodney, like Monke and Rupert, believed that the only victory was complete victory. His idea was that control of specific areas of interest was not the only goal of a battle fleet. The main objective was the destruction of the enemy's fleet. Rodney's first attempt was on April 17, 1780, near Martinique. It is set out in the following illustration Fig 2. 18

Even though this was not the major victory all had hoped for, the value of separating the enemy and concentrating fire upon them had been proven. Regardless of his opponents, Rodney claimed the responsibility for breaking the line as his own. He explains the move and results in a letter to Clerk in 1789:

Even though this was not the major victory all had hoped for, the value of separating the enemy and concentrating fire upon them had been proven. Regardless of his opponents, Rodney claimed the responsibility for breaking the line as his own. He explains the move and results in a letter to Clerk in 1789: