The Action at

Barba del Puerco

19th March 1810

by Richard 'Rifleman' Moore

| |

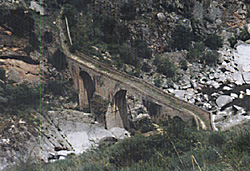

The bridge at Barba del Puerco (meaning "The Boar's Beard") crosses the Agueda east of Almeida just after the confluence with the Dos Cases rivulet flowing north from Fuentes D'Onoro. The combined waters flow through a deep gorge to join the great river Douro, in an area that is rather isolated and amidst terrain, which is very rough and inhospitable.

The action fought here between the 95th Rifles and part of the French forces under Ferey was brought about by the French occupying San Felices about two and a half miles away as the crow flies crossing the river by the bridge in late February 1810 and requisitioning all the food and drink from the poor Portuguese in the village on the west side.

Just before the now combined Rifle companies arrived at Barba del Puerco in force at dawn probably spoiling for a fight, the French pickets came running in giving the alarm and all their troops returned to San Felices the same way as they came, through the Pass. They probably feared an attack from a much larger force as they left behind in their haste the loaves from their 'requisitioned' flour scoured from the countryside baking in the village bread ovens, the appetising aroma of which the sharp noses of the 'riflemen soon found the location of they were then eaten by the 'green-jackets' for their daily bread! After a week gnawing on ship's biscuit, fresh baked bread is heavenly!

East of the village, the gorge through which the Agueda flows is steep and rocky winding down over a thousand feet is the San Felices Pass, crossing the river at its base by a narrow stone bridge, before coming up the other side again (another thousand feet). At first the way is not so much cobbled as 'pebbled' it soon plunges over the edge of the precipice and winds down a thousand feet through seventeen narrow hairpins down to the seventy yard long two yard wide bridge; infantry, a loaded mule or a led horse, can clamber up it single-file but nothing more. The way on the opposite side is just as steep as it ascends the crag. At the bottom of the pass on the San Felices side, a small robust stone built shepherds hut still clings to the hillside once, for some poor soul, briefly serving as a lonely frontier Customs post!

The Rifles established two sentries at the bridge, a guard under a sergeant of around a dozen men about fifty yards up the slope, and the remainder of the half strength company at the top of the pass in an orchard near the village church. A tent, a mattress and a chair nearby served as shelter for the Company officers in between doing their 'rounds'. The guards were changed every two hours.

The French picket of about seventy men stood exactly opposite the Rifles' on the opposite side, amidst some rude huts at this time the informal truce system that the British and French enjoyed later in the war was not yet common. Opportunists on both sides fired at each other across the chasm, sometimes just to relieve the boredom. It is not recorded if the Rifles ever hit anyone; but no casualties were incurred on their side from the French musketry at a range of between six and nine hundred yards!

Business as usual

It was business as usual on the night of 19th March 1810 Captain Peter O'Hare's Company had the post at the pass that particular night and he and one of his company officers, Lieutenant George Simmons, had just posted the sentries that evening and spoken to the sergeant on guard at the bridge. Simmons had crawled over the bridge later after dark looking for the French sentries finding none nearby he returned to the British side and joined O'Hare. They both started the long stroll up the path towards the village; arriving at the top about thirty minutes later they saw the rest of their men seated or lying around a cheerful campfire in their greatcoats, chatting or sharing a pipe. Simmons had done this 'tour of duty' before the first time he was on guard doing the rounds he had missed his turn going to visit the sentries by not turning left at the bakery; as a result he had walked around the outskirts and environs of Barba del Puerco all night until dawn, utterly lost!

It was the way of the Light Brigade under Craufurd to change not only the outpost sentries at irregular but frequent intervals, but also their positions. A password system was arranged to avoid any 'friendly fire' situations in the dark. Companies also exchanged their outposts frequently; officers at Barba del Puerco were required to observe and record the main flow of the Agueda river each day, and amend or update any map passed on by the previous 'garrison', and send out patrols under an NCO to regularly cover the entire area, day and night. 2

It had been raining heavily, and the rushing of the waters had partly obscured their approach from the ears of the sentries, who were both surprised before being able to give the alarm; one was killed and one badly wounded. But the clatter was heard the recently relieved sergeants' picket was not so easily despatched as they were wide awake and it was their firing that O'Hare and Simmons heard, as they discharged their rifles almost point-blank into the head of the four man abreast French storming column now rushing across the bridge, before retiring in good order up the face of the Pass, firing on the French pursuit as they stumbled uphill after them.

A sweating rifleman sent back from the bridge reported to O'Hare between gulping air into his aching lungs after running all the way up the cliff that the French were down there in strength; this message was in turn sent on by a different lad to the rest of the Rifles in the village. It was their habit that one company guarded the top of the pass at the end of a second pathway halfway up the climb from the bridge on the west side which went away to the south, another rifleman was sent off to inform them what was happening. O'Hare's Company less than 50 men leaving their knapsacks neatly piled around the campfire, quickly leapt up and assembled; loaded or freshened the priming of their rifles from the powder horn, and marched in quick time down to the top of the Pass and went straight into action.

At right, a French eye view of the crag.

O'Hare's company came on until they were almost on top of the first French troops at the head of the pathway down to the bridge they formed a line, fixed swords, fired one terrific volley, cheered at the top of their voices and charged. For thirty minutes the fighting developed at the top of the pass as breathless Frenchmen tried to climb up and into the village, and O'Hare's riflemen tried to pen them in at the top of the pass. A French volley from an hastily formed support line assembled by a brave French officer fired a volley in return; a Rifles officer 3 and several men fell the officer fell too leading the French counter charge; a rifleman put his rifle to his head as he lay on the ground and blew his brains out in revenge then fell himself, riddled with bullets from the furious French soldiers.

O'Hare had shouted to his men to take cover amongst the rocks he now shouted over the increasing din that they would Stand, denying the French a passage unless over his dead body. As if by prearranged signal, at that moment the other two 4 Rifle companies under Beckwith came down the hill cheering and swept into the fight with fixed swords they drove into and through the French at the head of the Pass and took some prisoners. O'Hare reformed his company, and followed them down the path. Beckwith 5 was levering a large stone with his sabre down the precipice trying to start a landslide to cause the French even more distress looking up, he ducked just in time to prevent a ball from a French musket deliberately aimed at him doing serious damage; it passed through his cap parting his hair! Lieutenant 'Rutu' Stewart and some riflemen engaged a party of French grenadiers that had succeeded in getting up the right-hand pathway in close combat Stewart was fighting three soldiers he killed one; one was shot at close range by Rifleman Ballard; and the other then surrendered.

Pursuit

The Rifles now pursued the retreating French in an more open and 'looser' order, descending the slopes and opening out to the flanks as much as the cliff permitted. Some men tumbled headlong down the mountainside; others pitched over the end of the path and came to grief in the darkness amongst large rocks. Parts of the French column were unmissable as they slipped and shoved their way down the steep pathway in a long snaking column going back the way they came, many soldiers carrying wounded comrades the odd shot rang out from a slowly descending rifleman as he glimpsed a target in the mass.

Ferey drew up about fifteen hundred soldiers in rough lines at the base of the French side of the pass. These troops were to be the support for the stormers if successful; they fired 'stepped' pelaton volleys across the gorge in support of the retiring stormers (and also to perhaps deceive the British into thinking that more troops were passing the bridge). The darkness concealed many of the riflemen as they clambered through and slithered over the rocks these close order but rather ill aimed and long-range volleys had little effect except to fill the gorge with gun-smoke, and adding to the noise of the rushing waters below.hundred soldiers in rough lines at the base of the French side of the pass. These troops were to be the support for the stormers if successful; they fired 'stepped' pelaton volleys across the gorge in support of the retiring stormers (and also to perhaps deceive the British into thinking that more troops were passing the bridge). The darkness concealed many of the riflemen as they clambered through and slithered over the rocks these closeorder but rather illaimed and longrange volleys had little effect except to fill the gorge with gun-smoke, and adding to the noise of the rushing waters below.

When the remains of the French storming party had crossed the bridge, the action devolved into 'sniping' from British and French alike; it soon ceased altogether at the behest of the officers the battle was over, and the French were heaving themselves back up the pass towards San Felices. Soldiers on both sides started to attend to the wounded a tremendous difficulty in view of the darkness and the fact that they had to be carried up a thousand feet of mountainside to the villages to have their wounds dressed.

Casualties overall were rather light, considering; the Rifles lost around 25 soldiers killed or wounded, including one officer the French more so, around 100 including three officers. Prisoners were taken on both sides, but were possibly exchanged soon after. 6 Four officers were killed and one severely wounded, all doing their duty trying to keep their men together in difficult situations; this invariably draws attention to oneself and officer casualties were unusually high here in the ratio to losses in the rank and file. Some French soldiers found by the Rifles at the bridgehead were found to have several wounds these brave lads probably fell in the first 'blast' from the dozen riflemen on guard and then got trampled over in the initial attack and also the ensuing retreat.

The flash of a muzzleloader being fired ruins night vision; and both reloading and aiming in the darkness must have been very difficult in the midst of sporadic friendly and incoming fire. A mistake or misfire would reduce the weapon to bayonet effectiveness only, as the long drawn out procedure of removing the bullet in the dark with the ball-puller would have taken far too long for most to consider worthwhile. In these circumstances, most veteran officers knew the importance of the initial well timed well aimed close order volley it was probably the only one they would be able to deliver with any certainty, before a night action became inextricably disorientated and they could hold command over and direct only the men in their immediate surroundings.

Although these soldiers were very fit men, their daily diet at this time did not engender stamina. Most of them would have been 'knocked up' and almost useless (in the military sense) for a long time days in some cases after this sort of activity. Once the adrenaline or anxiety wore off, they would have literally dropped down where they stood and gone to sleep if not closely supervised. 7

As the reports left by fast horse in the direction of Craufurd's headquarters, over the next few days afterwards the outpost at Barba del Puerco was reinforced by three more companies, from the 43rd and the 52nd Light Infantry. They didn't stay long. The next day the entire outpost moved to the fords at Villa de Ciervo, being replaced at the village by a vedette from the 1st Hussars, Kings German Legion. San Felices was reinforced by the French too, in the form of Loison's Brigade, but they didn't stay long as their rations ran out and they were at the end of a very lengthy supply line in an area already stripped bare by Ferey's troops.

8

The informer was found out discovered in the post-mortem of the battle. He came to a sticky end.

Wellington let it be known he was satisfied with the 95th Rifles' performance.

Craufurd also added his approbation, rare at the best of times. The French didn't attempt anything of the sort again; but not long afterwards Craufurd's established web of outposts 'quivered' at the touch of a major French incursion along this sector as a result of their successful captures of Cuidad Rodrigo and then Almeida. It was then an entire French army corps coming along to disturb the peace, but it would then be the entire Light Division they would have to contend with but that is another bridge, another place and another story!

The bridge was used once more for military purposes when the Governor and the former French garrison of Almeida used it to evade Wellington's clutches after the battle at Fuentes d'Onoro in 1811 after blowing up the fortress; this and their escape 9 going a good way to reducing the success of the British victory there on Massena's army (who still got the sack by Napoleon, though).

Today

The bridge is still there, but the village has changed its name; you can spot the correct road from three stone crosses placed on top of a prominent rock. The pathway from the village leaves the new metalled road which bears off left and you can slither over its cobbles and get your first daunting vertigo inducing look down at the bridge from climbing the granite 'Beckwith Rock' one hundred yards on the left; the path then slims down into a narrow walkway where two people can just travel abreast. Rails give a welcome hand at each hairpin bend for the brave climber on the way back up. You can spot where Ferey's rearguard/support must have stood and blazed away at the opposite slope. The echo must have been terrific!stood and blazed away at the opposite slope. The echo must have been terrific!

If you do explore here you must be reasonably fit and you should also take sensible precautions for the hike.

You can find more 'souvenirs' of the fight if you look hard enough but on a fine day, the spectacular views are enough and the lingering presence of riflemen still cling to the boulders, and their voices whispered to me in the wind.

1 The 'Light Division' was actually just coming into being in Wellington 'grand scheme'. Craufurd's Light Brigade had been a part of the Allied Third Division until very recently. Along with the Portuguese Cacadores, a battery of the RHA and the famous KGL Hussars, it was reconstituted the 'Light Division' around the time of this action.

With acknowledgements to Life of a Soldier, Jonathan Leach A British Rifle Man, George Simmons Adventures of a Soldier, Edward Costello The Autobiography of Sir Harry Smith and Recreating the 95th Rifleman, by R. RMoore

Rifleman Moore of the 95th Rifles has been an experienced reenactor for over 25 years; and is now a tour guide for "Sharpe's Peninsula" and "Over the Hills and Far away" for Midas Battlefield Tours.

|

Most engagements that are written about in the Peninsula fall into the category of "BIG"; no one writes much about the small skirmishes or patrol contacts therefore I offer a relatively unknown action at a small bridge in North-Central Portugal.

Most engagements that are written about in the Peninsula fall into the category of "BIG"; no one writes much about the small skirmishes or patrol contacts therefore I offer a relatively unknown action at a small bridge in North-Central Portugal.

One company of the 95th Rifles from Craufurd's Light Brigade 1 was sent to find the road there and reconnoitre the situation from bivouac. Another two companies were sent to support them the day after. For five days they watched the French from a secure position one more rifle company arrived a week later. The three companies in bivouac were probably very glad to see them as it made a move on the village very likely it can get pretty chilly up on a Portuguese mountain moor in March, and the very worst cottage is more preferable than sitting on your knapsack, greatcoat over your head in the rain, in the lee of a stone or bush!

One company of the 95th Rifles from Craufurd's Light Brigade 1 was sent to find the road there and reconnoitre the situation from bivouac. Another two companies were sent to support them the day after. For five days they watched the French from a secure position one more rifle company arrived a week later. The three companies in bivouac were probably very glad to see them as it made a move on the village very likely it can get pretty chilly up on a Portuguese mountain moor in March, and the very worst cottage is more preferable than sitting on your knapsack, greatcoat over your head in the rain, in the lee of a stone or bush!

The sergeants' guard at the bridge came back up at eleven thirty that night, having been duly relieved; suddenly at around midnight, the officers in their little tent leapt up hearing firing coming from deep in the Pass. An informer In the village of Barba del Puerco had given the French commander, Ferey, information on the Rifles' strength just over two hundred men and Ferey had assembled a volunteer storming party of six hundred Grenadiers and Voltigeurs, who dropped their knapsacks at the village of San Felices and after the short march to the head of the Pass had crept down their side of the mountain after a smaller 'Forlorn Hope', covering their uniforms with their greatcoats ... and who had leapt out on the two riflemen on sentry at the bridge in the dark.

The sergeants' guard at the bridge came back up at eleven thirty that night, having been duly relieved; suddenly at around midnight, the officers in their little tent leapt up hearing firing coming from deep in the Pass. An informer In the village of Barba del Puerco had given the French commander, Ferey, information on the Rifles' strength just over two hundred men and Ferey had assembled a volunteer storming party of six hundred Grenadiers and Voltigeurs, who dropped their knapsacks at the village of San Felices and after the short march to the head of the Pass had crept down their side of the mountain after a smaller 'Forlorn Hope', covering their uniforms with their greatcoats ... and who had leapt out on the two riflemen on sentry at the bridge in the dark.

The French were now almost up the 'British' side of the pass the difficulty of ascending the acclivity had been partly alleviated for them by the moon rising and showing them the path; it also unfortunately for them anyway showed to the retiring sergeants' guard at the top the French troops huddled together and struggling up the snaking steep path, and some of the leaders fell to the accurate aimed fire of the Baker rifle, the muzzle flashes lighting up the night.

The French were now almost up the 'British' side of the pass the difficulty of ascending the acclivity had been partly alleviated for them by the moon rising and showing them the path; it also unfortunately for them anyway showed to the retiring sergeants' guard at the top the French troops huddled together and struggling up the snaking steep path, and some of the leaders fell to the accurate aimed fire of the Baker rifle, the muzzle flashes lighting up the night.

The shepherd's hut especially on a hot day smells foul inside. I made a very interesting little Napoleonic find in the cave near the bridge after a brief look around. A nearby small stationhouse near the bridge contains some sort of hydroelectric facility for the pipeline that drops down from on high and small pylons take the generated current away. The graffiti has to do with Spain, accused more and more often these days of pinching Portugal's water by building more dams. Other than that, the place is exactly the same as in 1810. The Agueda still runs fast and loud the volume depending on the season and you can walk from 'Barba del Puerco' to San Felices in two hours using the bridge. The main road bridge in this sector is five miles upstream to the south-east. Eagles nest in the top crag just upstream and can be seen easily with field glasses from the bridge.

The shepherd's hut especially on a hot day smells foul inside. I made a very interesting little Napoleonic find in the cave near the bridge after a brief look around. A nearby small stationhouse near the bridge contains some sort of hydroelectric facility for the pipeline that drops down from on high and small pylons take the generated current away. The graffiti has to do with Spain, accused more and more often these days of pinching Portugal's water by building more dams. Other than that, the place is exactly the same as in 1810. The Agueda still runs fast and loud the volume depending on the season and you can walk from 'Barba del Puerco' to San Felices in two hours using the bridge. The main road bridge in this sector is five miles upstream to the south-east. Eagles nest in the top crag just upstream and can be seen easily with field glasses from the bridge.