The Battle of Hohenlinden

The Decisive Stroke

December 3, 1800

Article and Photos by James Arnold, USA

| |

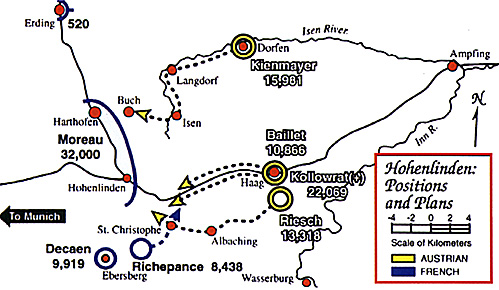

The Battle of Hohenlinden proved to be the War of the Second Coalition's decisive engagement. Napoleon Bonaparte knew that France would accept his rule only if he gained military victories that brought peace. Whereas the Battle of Marengo temporarily cemented Napoleon Bonaparte's place as First Consul, it was Hohenlinden that yielded the Peace of Amiens. Fought in Bavaria on December 3, 1800, the battle pitted about 62,000 Austrians under the nominal command of the young, brash, and inexperienced Erzherzog Johann against 51,500 French commanded by General Jean Moreau.

In typical Habsburg fashion, the Austrians advanced using four converging columns. Their plan was to knock aside any enemy they encountered and continue toward Munich. Moreau deployed his Army of the Rhine masterfully. His plan called for 32,500 men to defend his left and center on the open ground of the Hohenlinden plain while 19,000 enveloped the Austrian left flank. It was a calculated risk. His flank force would have to march through thick forest in winter weather in order to gain the Haag-Hohenlinden highway along which marched the central Austrian column. In such conditions, the unexpected was likely to occur. Success depended upon the performance of the division assigned to lead the envelopment. We pick up the story of that division's exploits as described in my newest book, Marengo and Hohenlinden: Napoleon's Rise to Power.

General of division Antoine Richepance began his march before first light. The van of the division was traversing the intermediate objective of St. Christoph at 7:15 a.m. when a snow squall descended, reducing visibility to ten paces or less. The guide got lost. The cloying mud grabbed at soldiers' boots and horses' shoes. In an effort to avoid boggy sections, the mounted units frequently had to move cross country. Richepance later reported that it seemed that the cavalry had to take two steps to the side to progress one step forward. After marching another half mile, someone detected an enemy presence on a rise overlooking the column's left flank. They were the two Austrian grenadier battalions that had been sent on a reconnaissance toward St. Christoph. At short range the grenadiers shot into the middle of Richepance's column. Their fire felled some battery horses at the bottom of a defile. The blockage separated the column into two sections. Worse, the surprise volley caused a small panic. Exhibiting the characteristic front line leadership that was to propel him far, general of brigade Jean-Baptiste Drouet rode amid the men to restore order. Then he sent the 5th Hussars and some infantry to drive back the grenadiers.

The front of the column ignored this uproar and continued its march until once again the guide got lost. This would not do. Richepance, who was with the forward element, halted the column. He sent two infantry companies to assist the 5th Hussars in clearing the flank and dispatched patrols to the neighboring farms to secure a new guide. This guide told Richepance that Maintenbeth, the division's next objective, was only a fifteen minute walk away.

Suddenly, as if to confirm the guide's words, visibility improved and the general could see the base of the hill on which sat Maintenbeth. With the 1st Chasseurs à cheval leading the way, the column resumed its march.

At 9 a.m. the forward elements of Richepance's division, those units which had passed the defile before it became blocked, approached Maitenbeth. At this point Richepance faced a decision. He knew an Austrian force had severed his division. The noise of combat continued back at the defile. He did not know how large was the enemy force advancing against his flank. To the north and northwest he could hear the din of battle emanating from the Hohenlinden plain. He believed that the Austrian units involved in this fight had no idea of his presence.

What to do?

Many, if not most, generals would have given first priority to saving the division by sending a significant force counter-marching to clear the division's flank and rear while the remaining units stood on the defensive. To his great credit, Richepance resolved to sacrifice the rear half of his division if necessary in order to use the units at hand to attack the Austrian rear. In the words of a French history written twenty years later, "This sublime decision...came to be regarded as the decisive cause" of the battle's outcome. [1]

Richepance sent a courier spurring to Drouet with instructions to hold his ground until relieved by Decaen's division, which he knew would be following somewhere to the rear. Then he ordered his available units, which numbered about 5,600 men, to deploy for an assault.

The 8th and 48th Demi-brigades, the 1st Chasseurs à cheval, and a six-gun battery prepared for action. The grenadiers of the 8th Demi-brigade were in a battle frenzy. Screaming 'Kill! Kill!', they spearheaded the advance into the hamlet of Marsmaier, which stood down slope from Maitenbeth. To their surprise, Marsmaier was not defended. Instead, the grenadiers encountered a detachment of Nassau Cuirassiers, many of whom were dismounted and taking their ease. After securing prisoners, the grenadiers continued though the hamlet and then paused to align with their parent unit. The 8th Demi-brigade formed in line parallel to the Haag-Hohenlinden highway. The battery took position to its front while the cavalry secured the right flank. In this position the French were at the base of a knoll. They could see neither the top nor the far side.

Unbeknownst to Richepance, if he advanced over the rise, he would sever FML Kollowrat's column. Most of Kollowrat's force had already passed to the west where they were engaged with Grouchy near Hohenlinden. Just over the knoll and extending east from Strassmair there remained five and one-half squadrons of Bavarian chevau-legers, Kollowrat's trains, the reserve artillery, and GM Christian Wolfskehl's cuirassier brigade. FML Johannes Liechtenstein commanded this group. He and his men were just approaching Strassmair when some fugitives from the cuirassier detachment in Marsmaier arrived with the news of Richepance's presence. Liechtenstein immediately deployed the Lorraine and the Albert Cuirassiers in two lines on the slope north of the highway. He ordered a battery of eight 12-pounders to cover this deployment.

During this time, Richepance had ridden to the top of the knoll from where he could look east and north and see the highway as it weaved through the forest. More importantly, he saw Wolfskehl's cuirassiers. If the Austrians realized how feeble was his force, Richepance judged his situation hopeless. Without even waiting for the arrival of the 48th Demi-brigade, he resolved to press forward. The 1st Chasseurs à cheval charged in line toward the cuirassiers. Because of a fold in the ground they did not see the nearby Bavarian light horse. Three Bavarian squadrons charged against the Chasseurs' right flank and sent the unit flying back to its original position. Here was a dangerous moment.

The retiring Chasseurs were intermixed with the divisional battery and with parts of the 8th Demi-brigade. Saber-wielding Bavarian chevau-legers were hot on their heels. Yet the French infantry remained steady and managed to drive off the Bavarians. Because they were not yet deployed, the Habsburg cuirassiers did not participate in the fight.

By this time the 48th Demi-brigade had arrived to take position to the left of the 8th. Undaunted by the near disaster, Richepance retained his resolve to "form in mass on the grand route and march, rapidly like a thunderbolt, against the enemy's rear."[2]

He had his infantry form battalion columns with the artillery in the intervals. The 1st Chasseurs à cheval continued to guard the right flank against another eruption of enemy cavalry. Spreading itself thin, it also screened the front of the two demi-brigades. Richepance intended to follow the highway toward Hohenlinden and attack Kollowrat's rear. This required several changes of formation and facing, all of which were performed under fire from the Habsburg 12-pounders.

His infantry were equal to the task. On a front extending across the highway and into the woods, Richepance's force marched on Hohenlinden. One of his aides-de-camp described the confused nature of the fighting:

"While leading a column I found myself attacked at a point where I had no idea that there were Austrians present. I was separated from the main body and was alone with three battalions, completely enveloped by the enemy. By hand to hand combat, I successfully forced a passage to rejoin my general." [3]

Around 10 a.m. Erzherzog Johann received a report about Richepance's movements. Most of his advisors believed that this French force must be an isolated group fleeing before the Austrian advance. Chief of Staff Weyrother galloped into the forest to investigate personally. The Bavarian Preysing battalion followed him as best it could. Weyrother encountered two additional Bavarian battalions that Kollowrat had previously ordered to march on St. Christoph. He grouped them to form a striking force based around the Preysing battalion. The Stengel battalion supported the left flank while the Schlossberg battalion provided a reserve. A four-gun Bavarian horse battery joined the command and galloped to a position near the highway. At about the same time, Kollowrat, who had independently become alarmed at the sounds of firing about Maitenbeth, sent GM Carl Wrede with two Bavarian battalions toward that village. [4]

The 48th Demi-brigade was the first of Richepance's units to contact these forces when it received three volleys of canister fire from the Bavarian horse battery. The nearest battalion column shuddered and closed ranks. Urged on by its officers, it delivered a spirited bayonet charge that overran the battery. Richepance's divisional battery deployed to support the infantry. It fired along the highway where one of the first rounds found Colonel Weyrother. Wounded, with his horse killed beneath him, Weyrother was knocked out of action at a critical time. Having conquered the battery, the 48th continued west along the highway. On either side the voltigeur companies deployed in the woods in skirmish order. The 48th shouldered its way past numerous caissons and wagons until it encountered Wrede's two Bavarian battalions.

This could well be the decisive engagement and Richepance knew it. He called out to the 48th's grenadiers: "what do you think about those men there?" The grenadiers sternly replied, "General, they are f....d" [5]

A fierce, close-range struggle ensued. Perhaps now the Austrians paid the price for having denigrated Bavarian fighting ability by calling them mere mercenaries. Although the Bavarians repulsed the French surge four or five times, in the end they lacked the indomitable spirit to tilt the balance in their favor. Leaving the highway littered with their dead, the Bavarians yielded. It was 10:30 a.m.

7Throughout the anxious morning, General Jean Moreau had maintained his headquarters at Hohenlinden. He had heard nothing from Richepance, nor had he expected to. He had witnessed the Austrian buildup on the heights overlooking Hohenlinden and seen a series of determined assaults against Grouchy and Ney. As noon approached, he perceived that the Austrian assaults against his right had lost momentum. He detected a hesitation in their subsequent maneuvers. In the words of the French historian Ernest Picard, "With a wisdom that does honor to his grasp of the battlefield", he deduced that the Austrian uncertainty was due to Richepance. [6]

This was the moment Moreau had been waiting for. He immediately ordered Grenier's wing to assume the offensive. Ney was to attack directly into the defile where the highway entered the open ground. Grouchy was to crush the Austrian left flank.

Ney stripped forces from his left in order to concentrate strength on his right. His divisional horse artillery delivered a punishing preparatory bombardment. Then Ney, exhibiting his renowned front line leadership, conducted a combined arms assault. The Austrians were tired from their own failed attacks and nervous about the firing they heard to their left and rear. Consequently they offered a feeble resistance. Ney's men drove them through the woods and captured ten cannons and 1,000 prisoners.

Grouchy arrayed his three demi-brigades in battalion column with two forward and one in reserve and advanced eastward. Kollowrat desperately committed his last two grenadier battalions to stem the tide. But here too the Austrians were dispirited. Austrian officers urged them forward but the grenadiers perceived that they were entering a trap with Grouchy to their front, Ney on their right, and Richepance on their left. Their advance lacked conviction and Grouchy quickly repulsed them. To make matters worse for the Austrians, at this juncture the first units of Decaen's division entered the battle.

Decaen's men had been on the march since 5 a.m. From the beginning, Decaen had been very anxious about his line of march. He and Richepance had exchanged messages during the night. They informed Decaen that Richepance was abandoning his outpost line, which was in contact with an Austrian force of unknown size in order to concentrate manpower for the flank march. However wise from Richepance's perspective, the news distressed Decaen. He worried that the Austrians would enter the void left by Richepance's departure and attack his open right flank. Whereas a Habsburg general might have been rendered inert by his concerns, or at least detached a strong force to address the unknown, after much anxious musing Decaen resolved to carry through with his orders. He ordered his commissary officers to distribute a full measure of gut-wrenching army brandy to the rank and file (one wonders if in order to fortify himself Decaen also partook) and ordered the advance.

As the division approached St. Christoph and the terrain opened up a little, it encountered a fleeing mass of vivandières' wagons and carts as well as ammunition and equipment wagons. Decaen did not know that this was part of the panic triggered by the combat at the defile that had originally severed Richepance's division. Decaen ordered his sappers to the front to clear a path. The leading units, general of brigade Pierre Durutte's French infantry and the Polish Legion, shouldered their way through the snarl and found enough space to deploy in a line of platoon columns. In this formation they proceeded toward St. Christoph.

By 11 a.m. Decaen found Generals Louis Sahuc and Drouet. They told him that the tactical situation was terribly jumbled. A heavy snowfall so reduced visibility that Decaen had to rely upon sound alone to make his dispositions. Hearing a sudden burst of fire to the right he asked Drouet what it meant. "Oh! The enemy is flanking us" came the reply. "Very well!" Decaen responded, "If they are flanking us, we will flank them." Decaen expressed similar confidence moments later when one of Moreau's aides-de- camp rode up and requested information. The general instructed the aide to tell Moreau that the situation was "a little confused" but not to worry because he expected to straighten matters out soon. [7]

Decaen had confronted a fast-changing, uncertain situation. Unlike his Austrian counterparts, he reacted confidently and aggressively.

Still, breaking through the first layer of Habsburg resistance proved difficult. A battalion of the 14th Light, accompanied by a cavalry squadron commanded by 'the intrepid Montalon', spearheaded the attack. As the cavalry charged, Montalon's horse fell dead beneath him. He shook himself off and rose to join the infantry. He was subsequently seen leading small knots of men directly at the Austrians during the back and forth fighting. Surprisingly, Montalon survived his infantry service and was alive to witness the tactically decisive intervention of the 2nd Polish Legion. This unit had been raised the previous year in Metz and Strasbourg using veteran cadres from the Italian campaign. When it pitched in, the Austrians ceded their ground for a last time. Just then the sun broke through the clouds as if to celebrate the triumph.

Decaen's division freed Drouet's force from its prolonged struggle around the defile. Drouet reassembled his half of Richepance's division and marched on Maitenbeth. Decaen, in turn, ordered the Polish Legion to assist Drouet. The Polish Legion debauched onto the highway near the Schimmelberg. It found itself in the midst of the Austrian artillery park. The Poles' unexpected appearance broke the already wavering Austrians. It seemed to them that the woods contained countless hostile columns that were erupting at will onto the highway. The only avenue to safety and freedom was to the north. Kollowrat's close order formations dissolved into untidy knots of fleeing soldiers running through the woods. The Habsburg drivers cut the traces and abandoned their vehicles to escape. Soon fallen soldiers and overturned cannons littered the highway. The rout was on with the flying soldiers spreading terror and confusion.

The experience of a French Chasseur named Côteboeuf and a Polish lancer named Ivisen highlights the collapse in Austrian morale. Côteboeuf galloped ahead of his unit and encountered some 50 Austrian infantry. Undaunted, he glanced over his shoulder and shouted out, "Charge, the 4th!" The Austrians laid down their muskets until they perceived that they faced a solitary rider. They began picking up their weapons when Ivisen appeared. Although this changed the odds to one versus twenty-five, what was more important was that apparently the Austrians belonged to a regiment recruited in Galicia, because Ivisen addressed them in their native Polish. His powers of persuasion were equal to the task and once again the infantry laid down their arms.

Back on the highway, Ney's men continued their drive until they met Richepance's 48th Demi-brigade. Richepance was not yet content with what had been accomplished. His thoughts centered on the scattered Austrian forces which he had bypassed. Accordingly, he turned his men around again, and marched toward Maitenbeth. Near that village the 8th Demi-brigade and 1st Chasseurs à cheval had been charged repeatedly by Wolfskehl's cuirassiers. During these actions the French general of brigade and future Imperial Guard general, Frederic Walther, fell with a grievous wound. On the Austrian side, Colonel Josef Radetzky, the future field marshal, was also knocked out of action. Suddenly some Austrian infantry appeared on the 8th's left flank. Their arrival showed that in the forests of Hohenlinden the surprise eruption of hostile soldiers on one's flanks could beset either side. The 8th recoiled from the contact. The Austrians, in turn, freed numerous prisoners who had been held in the hamlet and then continued their retreat.

It was 2:30 when Richepance counter-marched the 48th eastward to support the 8th. The two demi-brigades straddled the highway from where they repelled one more charge from the cuirassiers. As the Austrian heavy horsemen left the field, Ney's division closed up on Richepance's left. Together the victorious French marched in pursuit. Perhaps only now could Richepance take stock of what he had accomplished. He later paid tribute to his men when he wrote that the memory he would retain for the rest of his life was how his soldiers' conduct gave him a carefree confidence throughout the battle. Because he intimately understood his soldiers' capabilities, Richepance had taken near reckless gambles and won out.

The casualty lists underscore how one-sided was Moreau's victory. The Austrians lost 798 killed, 3,687 wounded while yielding at least 7,195 prisoners, 50 artillery pieces, and 85 caissons. Throughout its many campaigns since the beginning of the Seven Years' War, the Austrian army had never lost so much artillery. The Bavarians suffered 24 killed and 90 wounded while yielding 1,754 prisoners, 26 artillery pieces, and 36 caissons. Typically, it is impossible to tabulate precisely French losses. The French probably lost nearly 3,000 along with one artillery piece and two caissons. [8]

Putting aside the disparity in captured artillery, the Army of the Rhine still enjoyed a favorable casualty ratio versus the Austrians of between four and five to one.

When news of Hohenlinden reached Paris five days after the battle, First Consul Bonaparte "literally danced for joy." [9] In a letter to Moreau he handsomely praised the general, describing his maneuvers as "beautiful and wise". [10]

Indeed, Moreau had devised an elegant plan and stuck to it during the battle's uncertain early hours. Well might General Grouchy later say, in a letter to his wife, "we have won the most complete victory of the war." [11]

At the time, the Army of the Rhine had no doubt that Antoine Richepance had been the brightest star amid a shining galaxy that included two future marshals of France, Ney and Grouchy. However, as part of the suppression of prominent officers in the Army of the Rhine, Bonaparte placed Richepance on the inactive list in 1801. Still, had he lived, Richepance would have risen high. Instead, in April 1802 Bonaparte dispatched him to Guadeloupe to serve as Governor-General. Four months later he was dead, a victim of yellow fever.

James R. Arnold is a military historian and the author of fourteen books including Crisis on the Danube: Napoleon's Austrian Campaign of 1809 and Napoleon Conquers Austria: The 1809 Campaign for Vienna.

Marengo and Hohenlinden: Napoleon's Rise to Power can be previewed more fully at www.napoleonbooks.com. It is available directly from the author at Napoleon Books, 616 Little Dry Hollow, Lexington, VA, 24450 USA. For UK customers send a cheque for £ 23.00 plus £ 2.85 pounds shipping (book will be mailed from UK upon receipt of cheque in US) For US customers $38.00 plus $3.50 shipping.

[1] Victoires, Conquetes, Desastres, Revers et Guerres Civiles des Francais, XIII (Paris, 1820) p. 190.

More Hohenlinden

|

Richepance's approach march through forest near where he got lost and had to summon new guides.

Richepance's approach march through forest near where he got lost and had to summon new guides.

The ground near Maitenbeth, where Bavarians engaged French chasseurs.

The ground near Maitenbeth, where Bavarians engaged French chasseurs.

View from hill at Maitenbeth towards the Grosshaager Forst.

View from hill at Maitenbeth towards the Grosshaager Forst.

The hohenlinden plain, where Grouchy and Ney deployed, looked towards the forest from where the Austrians debouched.

The hohenlinden plain, where Grouchy and Ney deployed, looked towards the forest from where the Austrians debouched.