The French Repulse at Heilsberg

10th June 1807

by Patrick E. Wilson

| |

In the early June of 1807 the French and Russo-Prussian Armies confronted each other in East Prussia along the Passarge river. They had been in winter quarters, reinforcing and recovering from their exhaustion following the Eylau campaign at the beginning of the year. The French army had been particularly hard hit and Napoleon had had to draw on reinforcements from as far as field as Italy to replace the losses he had sustained. In June 1807 he had around 150,000 men available to face approximately 110,000 Russians and Prussians, and since the successful conclusion of the siege of Danzig, which had ended at the end of May, there was every likelihood of a French victory in the new campaign. As Napoleon would be able to concentrate upon defeating the main Russian field army.

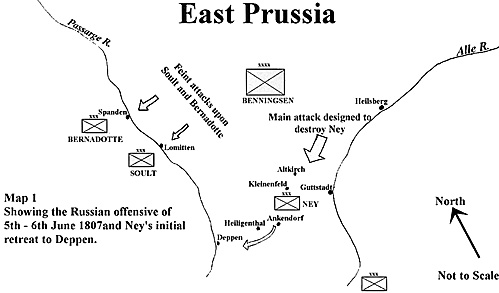

However the Russian Commander-in-chief, Count Levin August Benningsen, had other ideas and had a plan to snatch an early victory over the French. This involved a concentrated attack upon the French Corps of Marshal Michel Ney, who held an advanced position in front of the rest of the French army. Benningsen believed he could attack and destroy Ney's Corps before his colleagues could effectively intervene to save him. Such a victory might, perhaps, encourage Austria to intervene in the conflict, as the Austrian Commander-in-chief, Archduke Charles, needed clear and distinct victories before he would risk committing his Army to any conflict. However, Benningsen's initial plan did nut supply the result he desired as Marshal Ney proved a brilliant general at extracting himself from perilous situations, though it did bring about the Battle of Heilsberg. A clear Russian victory. Unfortunately this was to be overshadowed by a more decisive French victory four days later at Friedland. This essay will attempt to describe Benningsen's initial plan and attack on Marshal Ney, and his often forgotten victory at Heilsberg.

Benningsen's plan though simple enough in concept developed into a rather complicated series of manoeuvres and feints, which can be best described as a feint by General L'Estocq's Prussians upon Marshal Bernadotte's Corps in the Spandan area, another feint by General Doctorov's Russians (7th and 8th divisions) upon Marshal Soult's in the Lomitten area. Both these feint's were intended to keep Bernadotte and Soult occupied whilst the main Russian attack fell upon Marshal Ney. For the main attack upon Ney four separate columns were to be deployed, an advanced guard under General Bagration, the main assault under General Sacken (2nd, 3rd and 14th divisions) and two enveloping columns of a division each. In support of these formations stood the Grand-Duke Constantine and the Russian Imperial Guard. The plan had in its favour the fact that the French front line was surrounded by forests, which could be used to conceal the initial movements of the Russo-Prussian army.

Unfortunately, Marshal Ney seems to have had some warning that something was about to happen and had taken measures to concentrate his forces and even issued warnings to his colleagues, Soult to his left and Davoust to his right. In addition, the Prussians had attacked a day early and given Bernadotte full warning of Russo-Prussian intentions, and to make matters worse L'Estocq's attack was called off when the best idea would have been to continue at least until nightfall. On the correct day, 5th June 1807, L'Estocq renewed his attack upon Spandan but the French had been forewarned and L'Estocq's assault was met with heavy fire by the French 27th Legere Regiment and repulsed with heavy loss. The only good thing to emerge from this fight from a Prussian point of view was that Marshal Bernadotte wounded in the neck by a musket ball and thereby missed the reminder of the campaign, having to hand over command of his Corps to General Dupont. Meanwhile General Doctorov and his Russians were assaulting Marshal Soult's positions at Lomitten. It was a bit of a "see-saw" affair, one moment the Russians were successful in their assaults, the next moment the French had counter-attacked and recaptured the ground they had lust. The fight was pretty savage, both sides making free use of the bayonet and lasting from ten in the morning to eight in the evening, and so engaging Soult's attention that he was unable to assist Marshal Ney that day. Nut that Ney had needed his assistance for he had things well in hand at Guttstadt. At 6.00am Ney's outpost at Altkirch had been attacked and carried by Bagration's advance guard but on encountering one of Ney's divisions at Guttstadt, Bagration had halted to await support from General Sacken and the other columns. A bad mistake, as Ney counter-attacked and pushed Bagration back upon his own supports, fortunately for Bagration, Sacken now arrived and Ney had no option, considering the disparity in numbers, but to retreat immediately upon Ankendorf. A feat he accomplished, fighting all the way and making much use of swarms of skirmishers to impede the Russian advance. Taking up a position at Ankendorf and Heiligenthal he faced the Russians again with retreat only possible via two bridges, he had lost perhaps 2,000men and much of his baggage but had inflicted about 2,000 casualties upon the enemy, including two generals hers de combat. On the 6th June, the Russians found Ney still in position. An attack was immediately ordered with the intention of seizing the bridge at Deppen, on Ney's left, and cutting off the Marshal's line of retreat. However, though the Russians made significant progress against Ney's centre and left, the Russian general on his right manoeuvred himself out of the action and left Ney free to retreat by his right and thus Ney's Corps retreated safely across the Passarge with very little loss. Benningsen was understandably furious and blamed General Sacken for the failure of his plan to entrap and destroy Marshal Ney's Corps. Indeed, so bad was the venom of Benningsen's displeasure that General Sacken found himself obligated to leave the Russian army temporarily. That night Benningsen returned to Guttstadt with his headquarters, there he received a captured despatch that said Marshal Davoust threatened the Left of his army with at least 40,000 men. Consequently, by the 7th June Benningsen had ordered a retreat on Guttstadt and abandoned his offensive. Initially intending to fight at Guttstadt with his whole army, Benningsen changed his mind and redirected his army on Heilsberg, where he had established a fortified camp during the spring. To delay Napoleon' s expected pursuit, Benningsen placed Bagration in charge of the rearguard with Platov's Cossacks in close support. Bagration was the ideal choice, a Russian version of Ney, he had proved his worth in difficult situations again and again. Napoleon, in the meantime had ordered his Corps Commanders forward and by the 8th June, Marshals Soult, Ney, Murat and Davoust were in hot pursuit of Benningsen's legions. Marshal Soult was the first to become acquainted with the Russian's rearguard skills, as his cavalry general, Guyot, found himself ambushed near Kleinenfeld and paid for his error with his life. On the 9th June, it was Marshal Murat's turn to become acquainted with the prowess of Russian cavalry. As the Marshal neared Guttstadt with his cavalry, he was suddenly attacked by both Bagration's cavalry and Platov's Cossacks, who sought to gain time for the main Russian army to retreat on Heilsberg. They attacked with such fury that Murat's cavalry were nearly routed and only the arrival of Marshal Ney's infantry enabled Murat to stand his ground. Bagration, now faced by superior numbers, crossed the river Alle and burned the bridges behind him, ably covered all the time by Platov's dextrous Cossacks and his own artillery. Bagration then fell back on Heilsberg during the night, whilst the French occupied Guttstadt and sent detachments as far forward as Launau, a town a mere five miles from Heilsberg. All was now set for the Battle of Heilsberg the following day with Soult at Altkirch, Ney, Murat and the Guard at Guttstadt and others quickly approaching Guttstadt. Benningsen had the majority of his Army in and around Heilsberg. The town of Heilsberg lies astride the river Alle and is connected by five permanent bridges to which Benningsen had added a number of pontoon bridges to facilitate the movement of his Army. To the north, east and south of Heilsberg lay a series of ridges which Russian engineers had strengthened with redoubts, fleches and other small earthworks and it was on these ridges that Benningsen had deployed his Army for battle. On the left bank of the Alle he had the 8th, 6th, 5th and 4th divisions, supported by 27 squadrons of Prussian cavalry and 5 regiments of Cossacks at the village of Grossendorf. On the right bank stood the 14th, 7th, 3rd, 2nd and 1st divisions with detachments out in front on the road to Guttstadt, it was also down this road that Bagration and the rearguard were retreating. Though it was unlikely that the French would attack down this road, the Russian right was far stronger then the left, having more redoubts and the approach was very wooded giving little or no scope for proper deployment. The Left however offered much better opportunities for deployment as it was more open and in fact contained the road the French were actually advancing down. In front of the Russian position on the left lay open undulating plains, which were cut by the semi-circular course of the Spuibach stream. Two miles north of Heilsberg lay the wood of Lawden and a village of the same name, half a mile further on was the village of Langwiese and half a mile still further stood the village of Bewerick in front of a small stream. On the south side of this village there ran the road from Guttstadt and along this road there came in the early hours of the 10th June the French, headed by Marshal Murat and his Cavalry reserve, followed by General Savary, Marshal Soult and the division of General Verdier. It was about 10.00am when Benningsen received reports of a French advance upon his troops on the left bank, immediately he ordered forward a mixed brigade to delay them and Bagration to cross the Alle and more to support this force on the left bank. It was at the village of Bewerick that Bagration met up with the mixed brigade and the Russian outposts which were retiring before the French. quickly organising his forces behind a local brook, he placed a powerful battery of artillery on a height above Bewerick and halted the advance of Murat's cavalry. But then came Soult's and Savary's infantry, Soult's artillery under General Dulauloy quickly silenced Bagration's battery above Bewerwick and the French advanced again. Murat's cavalry advanced upon Lawden and its adjacent wood with Savary and Legrand (Soult's 3rd division) in close support, Soult himself with St. Hilaire and St. Cyr and his corps cavalry attacked Bagration at Bewerwick. Soult's leading division, St. Cyr, easily captured Bewerwick but had great difficulty in dislodging Bagration's infantry from beyond the brook and it would eventually require the intervention of St. Hilaire's division before any head way was made against Bagration's valiant infantry. Meanwhile, Murat's advance upon Lawden had come to an abrupt halt, assailed before he got beyond Langweise, Murat found himself driven back and forced to rely upon the support of Legrand and Savary to save his cavalry from utter ruin. Benningsen, noting the success of his attack, Bagration's cavalry bettered Murat's, ordered forward General Uvarov with 25 squadrons of cavalry (including 15 squadrons of Prussian cavalry) and regiments of Jägers to Bagration's support. Uvarov's subsequent attack completely dislocated Murat's cavalry and almost carried away Savary's infantry too but Savary and his men held firm in their squares, despite the fury of Uvarov's attacks and thus enabled Murat's cavalry to rally again and return to the attack. But Uvarov had had time to garrison the Lawden wood with his Jägers and moreover stalled the French attack for an hour or so. Murat's renewed attack, reinforced by fresh formations, eventually drove Uvarov's cavalry back upon the main Russian position and exposed Bagration's right flank, compelling him to withdraw across the Spuibach to avoid disaster. In this he was greatly helped by the fact that the Grand Duke Constantine had established a large battery of artillery on the right bank of the Alle and proceeded to enfilade St. Cyr's division as it attempted to pursue Bagration. Indeed, so successful was the fire of this battery that St. Cyr's division had to be replaced by St. Hilaire's division, which succeeded in crossing the Spuibach in pursuit of Bagration, despite heavy casualties from Constantine's battery. Meanwhile, Legrand, after the final repulse of Uvarov's cavalry had successfully taken Lawden and its wood from Uvarov's Jägers, despite some severe resistance. It was now about 6.00pm and as Bagration, Uvarov and their valiant troops fell back behind the main Russian position, Benningsen was able to bring all the guns of his position to bear on the rapidly advancing French. Soon over 150 guns were vomiting death and destruction upon the ranks of Legrand's, St. Hilaire's, St. Cyr's and Savary's divisions, the French however did nut flinch and marched boldly upon the Russian position. Legrand and Savary used what cover the Lawden wood could supply to aid their attack and aimed to seize one of the main Russian redoubts. Legrand's regiment, the 26th Legere, almost succeeded and drove the Russians from the redoubt but was almost immediately counter-attacked by three Russian regiments, who drove the 26th Legere out at bayonet point. The 26th Legere, broken and no doubt running for their lives, soon found themselves assailed by 15 squadrons of Prussian Uhlans and Dragoons, who in their pursuit collided with the French Cuirassier division of General Espagne, a frightful melee ensued and ended with the flight of Espagne's men and then the repulse of the Prussian cavalry by the remainder of Legrand's and Savary's men, who remained solid as rocks in their squares. An attempt by St. Hilaire to support Legrand with his 55th Ligne regiment, was utterly defeated, when the Prussian Death's Head Hussars pounced upon this regiment and routed it taking its eagle and killing its Colonel. Utter confusion now prevailed in this sector of the field as more and more Russian and Prussian cavalry pushed forward and attacked Legrand's and Savary's infantry, who had no option but to slowly fall back as Murat's cavalry now seemed so impotent in the face of the combined Russo-Prussian cavalry assault. Even the Cossacks joined in, Legrand's 18th Ligne regiment spent a greater part of the afternoon defending itself against incessant Cossack attacks and Legrand had to eventually send other troops to their support. The pressure upon Legrand and Savary must have been severe and they must have sighed huge sighs of relieve when General Verdier's division arrived headed by the energetic Marshal Lannes, fresh from his latest exploits covering the siege of Danzig. With the withdrawal of Legrand and Savary Soult's other two divisions, St. Hilaire's and St. Cyr's, had no chance of making any impact on Benningsen's position and thus, despite their great effort, they had to fall back out of range of those infernal Russian guns. By 9.00pm the French front lint: had fallen back beyond the Spuibach stream and the Battle of Heilsberg was almost at an end, the Russo-Prussian cavalry having returned to their positions in support of Benningsen's main line. Unfortunately for the men of Verdier's division, Marshal Lannes thought differently and ordered Verdier to assault the same redoubt Legrand had almost taken a few hours before, the result was a disaster. Verdier's division was shot to pieces by Russian artillery and Musketry fire as it emerged from the Lawden wood, losing over 2,000 men for no other purpose then Lannes' hot headedness. This was the last French attack of the day, a day that had seen the French out fought and to some extent, out generaled, for most of the day. Bagration, Uvarov and the Russo-Prussian cavalry had performed wonders, whilst the French, particularly Murat and later, perhaps, Lannes had totally mismanaged the situation, indeed Savary would remark of Murat: "It would be better for us if he were less brave and had a little more common sense." Again and again Murat and his much vaunted reserve cavalry had been bettered by the Russo-Prussian cavalry. Benningsen had fought the French to a standstill and repulsed all their attacks, it was a good tactical victory but would be made worthless on the following day when Davoust's Corps arrived to outflank Benningsen's position, as the British General Wilson wrote: "The enemy had indeed been repulsed in his attacks, and therefore been defeated in the object of his enterprise on Heilsberg, but the victory had not an influence beyond the moment..." The battle had been a murderous affair, the French had lust perhaps 12,000men, Soult alone admits to 8,286 for his three divisions, a third of his Corps' strength! The Russo-Prussian losses are difficult to calculate, Wilson gives them as one General killed (Koschin), four Generals wounded, 3 Jäger battalions destroyed and seven thousand men returned as killed or wounded. A couple of days later Benningsen would fight at Friedland, a grave error as he later freely admitted, and thereby lead Russia's best field army to utter defeat on the banks of the Alle, a river which but a few days before had witnessed one of Russia's best Napoleonic triumphs. A victory that has been overshadowed and almost forgotten because of the Battle of Friedland, a victory that Napoleon had no right to expect, and yet when the opportunity arrived he grasped it and hammered out a victory that is a worthy sister of Marengo, Austerlitz and Jena-Auerstädt. Sources and Further ReadingBecke, A.F. Friedland 1807 (Magenta Publications, 1991. Reprint of articles which first appeared in the Journal of the Royal Artillery.)

Battle of Heilsburg 1807: Large Maps (slow: 124K) Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #48 Back to First Empire List of Issues Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List © Copyright 1999 by First Empire. This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com |