The Eagle And Colour

Of The Légion Irlandaise

1804 - 1812

Stephen Ede-Borrett, UK

| |

The Légion Irlandaise, or Irish Legion [1], was raised by a decree of, the then, First Consul for Life Napoleon Bonaparte in 1803 in anticipation of a projected invasion of both Ireland and England. The Légion was intended as both a focal point for local recruits after the landing and as a training unit for the officer corps of the Army of a Republic of Ireland. However although the longed-for invasion and return home never materialised for the officers and men of the Légion they nonetheless were to fight well for the Emperor of the French until they were finally disbanded after the second Bourbon Restoration in 1815. The men (but not the fiercely Bonapartist Officers) were, incidentally, drafted into the unit which was later to become the famed French Foreign Legion. [2]

The Légion Irlandaise is one of those romantic military formations who have attracted attention far beyond their actual military importance, and it has rightly been termed "the last of the Wild Geese" [3]; although in its latter years whilst the majority of the officer corps remained Irish the rank and file were made up of almost very nationality in Europe. [4]

I was recently researching an article on the history of the Légion [5] and amongst the many sources consulted I found that I had a fair number which described or illustrated the Eagle and Colour. Before going very deep into the putting together of my large number of notes, therefore, I considered that one of the aspects which I had well covered and did not have to worry about was the colours - I could not have been more wrong as this essay is intended to show.

Although commissioned on 3rd April 1803 the Légion Irlandaise did not receive its first colour until the summer of 1804. The House of Challiot manufactured a simple colour for the Légion, which was delivered on 5th June. This colour had a green field with, on the obverse, an oval horizontal tricolour medallion (blue over white over red) at the centre, entirely surrounded with a gold laurel wreath, on the medallion was the legend

On the reverse was a similar medallion but in red surrounded by green laurel branches on a yellow background, on the medallion was the legend

This colour was carried on a simple staff with a gilt point and was adorned with a tricolour cravat. [6] Whatever the merits or otherwise of the unique appearance of their first colour the Légion were not to carry it for long and its subsequent whereabouts are completely unknown. Incidentally the only illustration that I have seen of this colour is in Military Flags of the World, 1618-1900 by Terry Wise (Poole 1980) which incorrectly shows the colour as fringed which it almost certainly was not. [7]

On December 5th 1804, at a great ceremony on the Champ de Mars, Napoleon presented the whole of the French army with new colours and standards, each staff topped with the soon to be legendary Eagle. Although barely at company strength the Légion Irlandaise was represented by Captains William Corbett and John Tennant and received a single Eagle, [8] with a new colour, from the hands of the Emperor personally. This Eagle would have differed not a jot from all of the other Eagles presented on that day [9] and, since the Légion bore no number, the plinth must have been quite plain as in the case of most other unnumbered units [10]. Incidentally the Eagle was always considered more important than the cloth 'flag' that accompanied it - so much so that it was sometimes carried on its own without the flag, although not, according to eyewitnesses, by the Légion Irlandaise (except, I would venture to suggest, in 1813-14 - see below). The actual colour presented on this occasion was however once again of a completely unique design - the only non-tricolour flag [11] ever presented [12] to the French Army of the First Empire, and it is its exact appearance that forms the main object of this essay.

There are two Primary sources for the actual appearance of the 1804 pattern (if we may call it that) colour of the Légion Irlandaise :

Pierre Charrié [13] says that the colour was entirely green and 80cm square : the obverse carrying the legend

The second source for the colour of the Légion Irlandaise is the memoirs of Captain Miles Byrne, an officer of the Légion (although in 1804 he was only a Lieutenant).

Byrne's memoirs [14] agree with the basic statement that the colour was green but he gives the obverse legend as:-

Subtly, but not substantially different from Charrié, however it has to be remembered that Byrne's memoirs were written down some years after the event and they do contain some elements known to be wrong alongside a mass of otherwise absolutely invaluable material.

With the two descriptions given above differing slightly it is useful to look at the appearance of the other, more normal, 1804 pattern French colours for although their basic design was totally different to that carried by the Légion the wording on the obverse is not.

Thus the 1804 pattern infantry colour presented on the Champ de Mars in December 1804 bore, in every case, the legend:

(or LÉGÈRE as appropriate) The similarity to the wording on the obverse of the colour of the Légion Irlandaise is immediately obvious, but no mention of Byrne's 'NAPOLÉON'.

Another Foreign Regiment, the Légion Hanovrienne (The Hannoverian Legion) received a colour at around this time [15], although without an Eagle, and here the legend on the obverse may be even more significant (albeit that it was borne on a standard 1804 pattern field) :

Again note the absence of the single word 'NAPOLÉON'.

Byrne's spurious numeral 'I' when coupled with the fact that every other colour presented by Napoleon bore not his name but his title would tend to discredit the first line of the Captain's description of the legend in favour of Mr Charrié's. Monarchs do not as a rule tend to refer to themselves by a numeral unless that numeral is greater than 1. Thus Napoleon's documents refer to 'NI' for 'Napoleon Imperator' but Napoleon the Third's refer to 'N.III.I.' for 'Napoléon Tertius Imperator' and a similar convention may be found in all other European monarchies and states. Napoleon only became 'Napoleon I' when there was a 'Napoleon III' [16].

The conclusion is therefore that the obverse was as described by Pierre Charrié, which is confirmed in most respects by Byrne. It is possible that Byrne's memory was confusing the inscription on the 1804 colour with that on the colour presented in 1812.

That the centre bore a large golden harp and a legend is agreed although the exact wording is slightly different between Charrié and Byrne, and here we have no other sources to guide us for this wording because of the uniqueness of the design.

Certainly Byrne's 'L'INDEPENDENCE D'IRLANDE' seems to make for grammatical sense since it would translate as 'The Independence of Ireland' but Charrié's 'INDÉPENDANCE DE L'IRLANDE' would translate as 'Independence of The Irish' a perhaps more Revolutionary and Napoleonic concept, particularly from a French point of view. This latter is also the legend as it appeared on the first pattern of colour for the Légion Irlandaise and would therefore be my preferred option, although it has to be admitted that there is little evidence either way and, whilst the wording of the first colour is an indication it can hardly be taken as anything of great substance.

Likewise except that the two parts of the legend appeared on separate lines how they were actually spaced on the colour and around the harp is unknown - my reconstruction below is therefore merely and honestly a guess.

As already mentioned the existence of a large golden on the reverse of the colour is not in dispute, undoubtedly as well, as with all similar contemporary illustrations of the Harp on Irish flags the strings were silver as they had been on the first colour - so far so good.

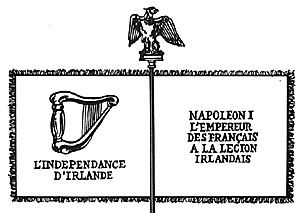

The only modern illustrations that I have seen of the reverse of this flag use Byrne's wording and a plain harp - see illustration II, but I would question the validity of this design of harp and to do so we have to go back to other contemporary sources, but first it may be useful to examine some other relevant points on the way.

Almost the entire officer corps of the Légion Irlandaise was derived from ex-members of Wolfe Tone's "Society of United Irishmen" movement which had led the short-lived and ill-timed 1798 rising in Ireland, and the Legion's green uniform undoubtedly owes its origins to the uniforms proposed in 1798 for the new 'Irish Army'.

The flag taken with Robert Emmet during the abortive rising of 1803 portrayed on it the Maiden Harp (illustration IV at right), the whole design being a variant of the seal of the United Irishmen (illustration V below), which again uses the Maiden Harp as its device, as does the seal designed by Emmet (reproduced in G.A.Hayes-McCoy's book, p. 121).

As Hayes-McCoy observes [18] whilst the plain fore-pillared harp is the most ancient form the Maiden Harp evolved to become the most common. Its origins can be traced back to the mid-seventeenth Century until by the early years of the Eighteenth the Maiden Harp is the most common form used on all Irish Flags.

Ironically the popularity of this form of harp can be most easily traced in the Heraldry of the monarchs of Great Britain :

The still-surviving velvet tabard [19] of Sir William Dugdale, Garter King-of-Arms from 1677-1686 shows, for Ireland, a harp with a lion's head topped fore-pillar [20] in its third quarter; but by the time of the Act of Union in 1707 the Royal Arms displayed, for Ireland, a full-blown Maiden Harp in the Third Quarter. This situation remained unchanged until the prudery of the Victorians swept away the lady's fulsome charms and the 1837 Royal Arms, still in use today, show a plain fore-pillar.

Also worth observing is the fact that the Maiden Harp is the form most commonly found on the colours and standards of the Irish-raised Regiments of the British Army of the period, both regular and Yeomanry/militia [21].

It can therefore be seen that during the period in question for the manufacture of this colour, i.e., the Summer and Autumn of 1804, not only was the Maiden Harp the most widely used symbol in use for Ireland by "foreigners" but it was also the preferred symbol of use by the Irish themselves - or at least those who chose to take up arms in one way or another, both for and against the British Crown.

All of this would seem to lead to the inexorable conclusion that the Maiden Harp is the most likely form to have appeared on the second pattern of colour of the Légion Irlandaise.

The positioning of the legend on the obverse merely seems to make more aesthetic sense, as I have said there is actually no real evidence either way.

The omission of the usually-shown fringing is as near a certainty as can be: French infantry colours were not fringed until the 1812 pattern and no colours of the 1804 pattern, to which this colour conforms in many ways, were so disfigured [23].

By 1812 the colour of the Légion Irlandaise described above was in a poor condition [24] and the Légion was designated to receive a new colour in line with the rest of the Army, both horse and foot, Guard and Line.

When the 1812 'Bardin Regulations' [25] came into force they brought with them (but not actually part of them it should be noted) a new design of colour and standards for the whole Army. As in 1804 this was to impose a uniform basic design of flag for all arms, only the size varying between cavalry and infantry, however, unlike in 1804, the Légion Irlandaise, which in 1811 had become the '3me Régiment Etrangère' (3rd Foreign Regiment), was not permitted any exclusion - their new colour was the same pattern as everyone else's.

The 1812 pattern colour was again 80cm square, but now with the addition of a golden fringe 2.5cm deep. It was of a true tricolour design of blue/white/red equal vertical bands (obverse reading from the left) and heavily embroidered with crowns (upper two corners), eagles (lower two corners), 'N' within a wreath (middle of each side), Imperial bees (top and lower edges, in three rows), stars (above each crown), and foliate designs (each side, both above and below the wreathed N). The obverse bore the same legend as the 1804 colour except that for the Légion Irlandaise this would now read:-

to reflect their new official designation. The obverse, which should have borne the battle honours in the form of the names of battles which the regiment had been at and where the Emperor had commanded in person, was blank save for the embroidery the regiment had never served at any of Napoleon's great victories. Whether the Légion ever actually carried this colour is unknown, certainly it cannot have been popular with the Irish Officers.

Charrié, Pierre

Drapeaux Et Étendards de la Revolution et de l'Empire; Paris 1982.

[1] To be absolutely pedantic the Legion Irlandaise was never actually a "Legion" at all. The concept of Legions as an all-arms. combined force originated during the Eighteenth Century and took the name from the Roman Legions of antiquity, themselves perceived as a self-contained 'mini-army'. The Légion Irlandaise only ever consisted of infantry and thus strictly does not qualify for the title by which it was always known, even to its contemporaries.

Related

|

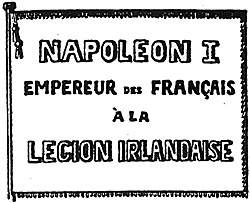

(An illustration of the obverse of a highly inaccurate reconstruction from Byrne's description is shown as illustration I (see at right): not only is the basic shape wrong but the wording is of an irregular size and the 'flag' has a fringe.).

Whilst Byrne agrees that the reverse bore a gold harp he says that the legend was:-

(An illustration of the obverse of a highly inaccurate reconstruction from Byrne's description is shown as illustration I (see at right): not only is the basic shape wrong but the wording is of an irregular size and the 'flag' has a fringe.).

Whilst Byrne agrees that the reverse bore a gold harp he says that the legend was:-

However Byrne is usually taken verbatim and Illustration II (see at right) shows the reconstruction that is almost invariably used.

However Byrne is usually taken verbatim and Illustration II (see at right) shows the reconstruction that is almost invariably used.

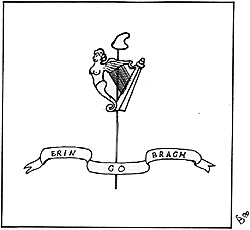

During the 1798 rising there were many examples of the rebels carrying green flags embellished with a gold harp [17] and Wolfe Tone's own design for the new Irish Flag (illustration III at left) clearly shows the form of harp as "The Maid of Erin Harp" or simply "The Maiden Harp", i.e., with the fore-pillar in the form of a female.

During the 1798 rising there were many examples of the rebels carrying green flags embellished with a gold harp [17] and Wolfe Tone's own design for the new Irish Flag (illustration III at left) clearly shows the form of harp as "The Maid of Erin Harp" or simply "The Maiden Harp", i.e., with the fore-pillar in the form of a female.

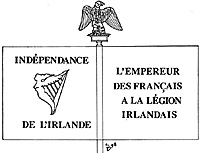

Putting together all of these snippets we can come to some fairly solid conclusions as the actual appearance of this colour, which I have reconstructed as illustration VI at right. The style of lettering and the unusual form of the accents over the 'E' and below the 'C' has been taken from surviving colours of the French 1804 pattern [22] - it would seem unlikely to have been different for the Légion Irlandaise especially bearing in mind the fact of the consistency of the wording of the obverse compared to the colours of the French Regiments as we have seen.

Putting together all of these snippets we can come to some fairly solid conclusions as the actual appearance of this colour, which I have reconstructed as illustration VI at right. The style of lettering and the unusual form of the accents over the 'E' and below the 'C' has been taken from surviving colours of the French 1804 pattern [22] - it would seem unlikely to have been different for the Légion Irlandaise especially bearing in mind the fact of the consistency of the wording of the obverse compared to the colours of the French Regiments as we have seen.