Battle of Orthez

27th February 1814

A chance Not Taken?

by Richard Dyson, UK

| |

The battle of Orthez, which occurred on the 27th of February 1814, at the close of the Peninsular war, is perhaps not as well known as some other Peninsular battles. The two principal English historians of the period, Oman and Napier,

[1]

treat it almost as just one episode in Wellington's advance into southern France in the late winter and spring of 1814. In one sense this is true, casualties on both sides were not that great and a much bloodier battle was fought at Toulouse just over a month later, on the 10th of April.

Orthez deserves more attention than this though, for it was a battle where Wellington did not have it all his own way, he had to work very hard to gain a victory. In the initial stages of the battle all of his attacks were repulsed, forcing Wellington to redeploy his forces. It then took several more hours of hard fighting to finally make the French troops retreat. At this point Wellington had a golden opportunity to destroy a large proportion of Soult's army. As we shall see however, this did not occur and Soult escaped to fight again. Wellington bore some responsibility for failing to vigorously pursue the French, something that has often been overlooked by previous commentators.

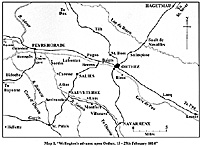

In early February 1814 the Allied army, stationed as far north as Bayonne on the Atlantic coast, was ready to take the offensive deep into France. Wellington planned to invest the fortress of Bayonne by crossing the river Adour a short distance below the town. He also aimed to push Soult's right wing over the rivers Bidouze and the Gave d'Oleron, partly to divert their attention away from Bayonne, but also, by forcing them eastwards, to open up a line of advance into the French interior.

On the 14th of February General Hill, the commander of Wellington's right wing, advanced and captured the town of Hellette, moving into Garris the next day. There a small battle was fought with the French rearguard, consisting of General Harispe's division and General Paris' brigade. Hill pushed the French troops aside and continued to advance, reaching the River Saison by the 17th of February. This was forded by an English infantry regiment near Arriverete and by the 18th Hill had reached the Gave d'Oleron at Sauveterre. [2]

Wellington's plan of crossing the Adour at Bayonne had meanwhile been held up by bad weather. He decided to concentrate his resources in the east and on the 21st of February ordered the 6th and Light divisions from the Bayonne area to support the attack on the Gave d'Oleron. [3] By the evening of the 23rd of February Wellington had the following units in position for an attack. Leaving aside the 1st division, which was investing Bayonne, Cole's 4th and Walker's 7th divisions, plus Colonel Vivian's brigade of cavalry, were under the command of Field Marshal Beresford at Hastingues and Oeyregave. The right wing of Wellington's army was further south. The 3rd division, commanded by General Picton, was south of Sauveterre, while General Clinton's 6th division was just opposite Montfort. General Hill had direct command of Alten's Light, Stewart's 2nd and Le Cor's Portugese division at Villenave. Two cavalry brigades, commanded by Generals Somerset and Fane, were also attached to the Allied right wing. [4] Excluding the units around Bayonne and a Spanish division on his extreme right flank, Wellington had about 46000 men under his command.

[5]

French

Facing Wellington were approximately 35000 French troops. [6] Marshal Soult had brought d'Erlon's corps of two divisions (under Generals Rouget and Darmagnac), from their posts on the right bank of the river Adour to join General Foy's division at Peyrehorade. [7]

Taupin's division held the French centre between Athos and Caresse. In the south Soult had stationed Villatte's division around Sauveterre and its bridgehead on the left bank of the Gave d'Oleron, with Harispe's division and Paris' brigade on the extreme left between Sauveterre and Navarrenx. [8] Soult's divisions were very thinly spread out, across a front of some 17 miles. They were thus vulnerable to a concentrated Allied attack on any particular part of the front.

This is what Wellington actually did on the 24th of February. Using Picton's 3rd division to make a feint against the bridgehead at Sauveterre, he pushed Hill's three divisions, the Light, 2nd and Portugese, across the relatively undefended ford at Villenave. The 6th division under Clinton crossed the Gave d'Oleron between Montfort and Laas. [9] Soult, seeing his left flank turned, issued orders on the evening of the 24th for his troops to fall back on the town of Orthez, situated on the right bank of the Gave de Pau and surrounded by hills that presented a good defensive position.

Overnight the three divisions of Foy, Darmagnac and Rouget withdrew to Orthez via the Bayonne road while Taupin's division fell back on Salies and then crossed the Gave de Pau at Berenx, destroying the bridge there. By daybreak on the 25th these four divisions had established themselves at Baigts, a small village just over two miles from Orthez. Villatte's division had meanwhile retreated directly into Orthez. At nine o'clock in the morning on the 25th Villatte abandoned the suburb of Depart, situated over the river from Orthez, and attempted to blow up the old bridge there. He was only partially successful however, for the broken stone still allowed a way across. [10] General Clausel, who commanded Harispe's division and Paris' brigade on the extreme left, took a lot longer to reach Orthez, not entering the town until the 26th of February. [11]

Hill resumed his advance on the 25th of February and by midday his corps had reached Depart. Hill ordered his artillery to open fire on the French troops in Orthez and at two p.m. several Allied battalions moved into Depart to try and capture the ruined bridge. They met heavy French resistance however and were unable to take their objective. The fighting lasted right up until nightfall. [12] The Allied forces suffered between two and three hundred casualties, the French troops one hundred. [13]

Hill's attack may have helped to persuade Soult that Wellington was going to make his main effort on the French left. Indeed on the same day Soult received reports, admittedly vague, of Allied Troops advancing on the town of Oloron, fourteen miles to the south-east of Orthez.

[14]

Wellington was instead aiming to turn Soult's right, not his left. He planned to cross the Gave de Pau north of Orthez and then force the French back as he had previously done at Arriverete and Villenave. One of Beresford's brigades, from the 4th division, crossed the Gave d'Oleron below Sordes on the 25th of February. The next day the other brigades of the 4th and 7th divisions crossed at the same spot and later forded the Gave de Pau. [15] Colonel Vivian's brigade of cavalry led the way and advancing down the main road to Orthez encountered some French chasseurs in the village of Puyoo. Vivian ordered his troops to charge and they pursued the French for two miles down the road, taking six prisoners before fatigue and a French counter-charge induced them to halt. [16]

The rest of Beresford's force followed Vivian down the same road and by 5 o'clock in the afternoon had reached the outskirts of Baigts. [17] Meanwhile Picton's 3rd division and Somerset's cavalry had moved through Salies in the morning of the 26th and in the afternoon, at about 4p.m., crossed the Gave de Pau near Berenx, thus joining up with Beresford. [18] Wellington had also moved the 6th and Light divisions to the ford at Berenx, though by nightfall on the 26th they were still on the south side of the river. Hill's 2nd division and the Portugese remained stationary outside Orthez throughout the day. [19]

Wellington had managed to assemble five infantry divisions and two cavalry brigades on the French right wing and all bar two infantry divisions were now across the Gave de Pau. He had thus once again succeeded in concentrating his forces and turning the French position. Wellington expected that Marshal Soult would now retreat as he had done before. On the evening of the 26th Wellington wrote a letter to General Hope, commander of the Allied troops at Bayonne, stating that, "The enemy's whole army were in front of Orthez; but I understand that they began to retire at dusk." [20] Even in the early hours of the 27th Wellington wrote to the Duc d'Angouleme, leader of the French royalists, "Today I go to Orthez, from where I will march forwards." [21]

Soult though was now preparing to fight. At his headquarters in Orthez he had received several reports of Wellington's moves, in particular Beresford's crossing of the Gave de Pau and his advance on Baigts. On the evening of the 26th of February Soult issued orders to his corps commanders to defend Orthez. General Reille was ordered to take command of Taupin's and Rouget's divisions, together with Paris' brigade, and hold a line at the hamlet of St Boes on the French right. The 21st Chasseurs a Cheval were also allocated to Reille. D'Erlon, with Foy's and Darmagnac's divisions, was to defend the French centre, his troops roughly parallel to the Orthez-Dax road. The 15th Chasseurs a Cheval were to support him. General Clausel was directed to position Harispe's division just behind Orthez with only a small detachment to defend the bridge there. Villatte's division was placed as a reserve, to support either the French left or right as circumstances dictated. [22]

In total Soult had 30500 infantry, 2000 cavalry and 1500 artillery with 48 guns in the immediate vicinity of Orthez. [23] Soult also stationed units to protect his extreme left flank. General Pierre Soult (The Marshal's brother and commander of the cavalry) was ordered to send the Legion Hautes-Pyrenees and the 22nd chasseurs to defend Pau. Two light cavalry regiments and the 25th light infantry regiment, under the command of General Berton, were instructed to guard the fords on the Gave de Pau between Orthez and Lescar. [24] Soult still anticipated an Allied attack in this direction. "I expect however that tomorrow the enemy will cross with some columns between Orthez and Lescar," wrote the Marshal in his despatch to Clarke, the minister of war, on the evening of the 26th. [25]

Soult fully expected to fight Wellington the next day. In the same letter as above he stated: "It is very likely that tomorrow there will be a battle, for the two armies are too near for one side or the other to avoid it." [26] Since the 14th of February Soult had retreated before Wellington's advance, so it is important to understand why the Marshal now felt that he had to make a stand. No direct evidence exists of Soult's intentions at this time, but he may have thought that if he did not offer battle Wellington would push him eastwards all the way to Toulouse, severing communications with the Bayonne garrison and leaving the way open for an advance to Bordeaux. It is equally possible that Soult believed that the good defensive terrain at Orthez offered him a chance to break down an Allied attack and thus gain a victory. Indeed on the 25th of February Soult had written to Clarke: "... I am determined to profit from the mistakes that he [Wellington] will make and to attack him the instant it appears favourable to me." [27]

Orthez certainly offered a strong defensive position, one that would be very difficult for the Allies to capture. A British officer serving in the Light division has left this vivid description:

"The position occupied by the enemy, as it appeared to me, was a height about a mile in length, in the shape of a crescent, having its concave side towards us. On the right the position was connected with some heights in its front by a ridge, on which, within musket-shot of their line, was the village of St Bois [Boes], which was strongly occupied. On their left, a branch similar to that on the right extended itself into the plain to the northward of Orthes. Though this was the appearance of the position on the front opposed to us, as far as I could learn, the heights receded behind the wings in such a way that the position could not be turned, except by a corps detached for that purpose. This with its compactness, and the tabular summit of the heights, which admitted a free space for manoeuvering, rendered the position strong, although there was nothing in the profile of the ground to make it paticularly so."

[28]

Seeing the French troops encamped upon the hills surrounding Orthez, Wellington himself realized that they were going to make a stand. An attack would be difficult, but Wellington really had no choice if he wanted to continue his advance. Just after dawn on the 27th of February there were 44000 Allied troops in the vicinity of Orthez; 39500 infantry, 3300 cavalry and 1200 artillery with 54 guns. [29]

On the left were Beresford's 4th and 7th divisions plus Vivian's cavalry brigade. The Allied centre was made up of the 3rd, 6th and Light divisions, together with Somerset's hussar brigade. The 6th and Light divisions had crossed the Gave de Pau in the early hours of the morning over a pontoon bridge. [30] Two miles away were Hill's detachment, the 2nd and Portugese divisions plus Fane's cavalry brigade, located to the south and east of Orthez.

No written orders detailing the Allied plan of attack have managed to survive, but from the reports writtten after the battle it is possible to deduce fairly accurately Wellington's initial moves. The 4th and 7th divisons, together with Vivian's cavalry, were instructed to attack the French right around the village of St Boes. General Picton was placed in overall command of the 3rd and 6th divisions and ordered to move along the great road leading from Peyrehorade to Orthez and then attack the heights on which the French centre stood. The Light division was placed in reserve for these two attacks and General Hill was instructed to cross the Gave de Pau and threaten the French left. [31] Wellington's aim was to use his left and centre as a hammer blow to break the French defence. Hill's corps was mainly to be used as a flanking attack. Events did not turn out exactly as Wellington had planned however.

At about 9 o'clock in the morning Sir Lowry Cole's 4th division, led by General Ross' brigade, commenced the attack. [32] It advanced towards the village of St Boes, held by the French 12th light infantry regiment. There was a short artillery duel and the French unit was soon pushed out of the village by the British infantry. Advancing out of St Boes however, the 4th division had to cross a narrow strip of land seperated by deep ravines. Cole was only able to deploy his forces on a narrow front and faced heavy resistance from Taupin's division. Several times the 4th division unsuccessfully charged the French positions, each time being repulsed by artillery fire and French counter-attacks. [33] A French eye-witness, Captain Edouard Lapene, who was an artillery officer in Taupin's division, has left a vivid description of the fighting

". . . our cannons . . . are charged with case-shot, and await the moment when the enemy will come out of the village in close column. They appear at last, and the guns start to fire. The English, hit by these deadly volleys received at close range, suddenly stop and begin to waver; on a second volley, they turn around. Attacked at the same time by the bayonettes of the division Taupin, they leave the village full of their dead. Three times the enemy marches with the greatest assurance against the batteries that they are on the point of storming; three times the division's regiments, supported by their artillery, executing the same manoeuvre, obtain the same success." [34]

The fighting in this sector of the battlefield lasted for three hours, [35] but by the end of this period Cole was hardly any further forward than when he had started.

Meanwhile General Picton in the Allied centre had been equally unsuccessful. Picton probably planned to advance only slightly forward and then attack when Beresford's troops had pushed back the French right wing. As one eye-witness wrote: ". . . Sir Thomas Picton, supported by two guns . . . marched his division left in front towards the enemy's centre position, and posted it in a ravine under cover of a little hill, ready to attack the French at that point as soon as circumstances should require." [36] However the failure of the 4th division's assault meant that Picton was unable to move forward any more, his flank might have been exposed to a French counter-attack: ". . . we were aware that the moment we should attempt to go forward, we would have been taken in flank by a large body of troops . . ." wrote an officer in the 45th Foot, part of the lead brigade of the 3rd division. [37] The 3rd and 6th divisions were forced to halt under heavy French fire. General Foy's division, immediately opposite, opened up with 4 pounder guns which, because they were situated behind a hillock, could not be effectively countered by the British artillery. [38] Picton's troops just had to stand there and put up with the French fire. "We were thus most provokingly brought to a complete stand, exposed to a heavy cannonade, and also to the fire of the infantry in our front ...", wrote the officer from the 45th. [39]

There is some evidence that part of the 3rd division was forced back by French counter-attacks. Captain Thackwell of the 15th Hussars, part of Somerset's cavalry brigade, reported in his diary that, ". . . our sharpshooters in the centre", having gained possession of a small hill, were ". . .driven back upon the column by a very superior force." [40] Colonel Colborne of the 52nd regiment of the Light dvision recalled at this time seeing ". . . Picton's divisions scattering to the left." [41]

So far the battle had not gone that well for the Allies. Wellington had seen Marshal Beresford's attack flounder upon the terrain and fierce French resistance and consequently Picton's troops also brought to a standstill. Soult's line had not been broken and his troops had hardly been driven back at all. Indeed there was the danger that the French, fortified by their success, might now take the initiative and launch an attack themselves. Wellington now decided to change his plans. The exact time was never recorded; a fair estimate puts it at twelve o'clock, allowing for the length of the fighting at St. Boes. As Wellington later recorded in his despatch:

" I therefore so far altered the plan of the action so as to as to order the immediate advance of the 3rd and 6th divisions, and I moved forward Colonel Barnard's brigade of the Light division to attack the left of the height on which the enemy's right stood." [42]

Focus

Wellington was now focusing his attention on Soult's centre by ordering the 3rd and 6th divisions to immediately attack there. More significantly the order for the Light division to attack the boundary between the French right and centre was an attempt to seperate the two corps of Reille and d'Erlon from each other, thus opening up a gap which Wellington could then exploit. Only one battalion of the Light division was available for action, the 52nd regiment, and it was this that Wellington now moved forward. Major George Napier, second-in-command of the regiment at the time, has left an account of what happened next:

"... I happened to be near Lord Wellington who was observing the army with his telescope, and perceiving an alteration to Marshal Soult's movements, he immediately altered the plan of his attack and ordered the 52nd Regiment to form line and march straight through the marsh and attack the centre of the enemy's position without delay. In a few minutes we were in full march, up to our knees every step in the bog, the enemy pouring a heavy and well-directed fire upon us from the height above, which we could not return . . . At last we made the enemy retire and gained the brow of the hill, and then dressed our line and commenced a heavy rolling fire in our turn, advancing at the same time." [43]

Just after Wellington gave this order he was struck in the thigh by a spent musket-ball. The wound was not serious though and Wellington was still able to ride. [44]

At approximately the same time Picton's 3rd division moved forward, with General Brisbane's brigade in the lead. General Clinton's 6th division brought up the rear of the attack. Resistance was fierce, especially from General Foy's division, but eventually the 3rd division reached its objective. "All the eleven regiments forming this division were desperately engaged, carrying hill after hill until they were at length observed climbing the enemy's grand position, under a loud cheering and the sound of light infantry bugles", wrote one witness. [45]

Colborne's 52nd regiment had opened up a sizeable gap between the two corps of Reille and d'Erlon. General Darmagnac, his flank threatened, ordered his division to withdraw. The other division of d'Erlon's corps, commanded by General Foy, was similarly pushed back by Picton to the convent of Bernardines from where it attempted to make a stand. [46]

Foy himself was wounded at about this time, hit in the shoulder by some shrapnel from an English Congreve rocket. The brave general walked unaided from the battlefield, and later made a full recovery from his wounds. [47] Foy's departure did though adversely affect his soldiers' morale, and his division retreated further. It was now about half-past two in the afternoon. Picton's troops were on the verge of reaching the Orthez - Dax road. Once there they could move up it and attack Reille's corps in the rear. To prevent this, Marshal Soult ordered his brother to instruct the 21st chasseurs to charge the Allies down this road; some guns of the 3rd division may also have provided a tempting target. [48] An English hussar officer, who actually knew some of the French chasseurs through encountering them on patrol, describes what then happened:

"It appears that young Soult thought that some of our guns, belonging to the third division, were so exposed as to be capable of being captured, and gave orders for these two unhappy squadrons to gallop through a deep lane, 'deboucher' on the open ground and charge them. The officer in command pointed out the risk his men would run, but on receiving in reply some cutting remark, nettling to his high feelings, he gave the word, gallop forward, and he and his chasseurs soon became, as he foresaw, entangled in the lanes, common around here, of ten to twenty feet deep. While in this predicament, a Portugese regiment came up on the brink, and with a volley laid nineteen out of every twenty on the ground. Our regiment was in support and came up just after this slaughter. These poor fellows and their horses lay so thick, with their swords and bridles still in their hands, that the road was impassible, and we were obliged to break into the fields in order to proceed in pursuit of the enemy." [49]

While all this activity was going on Marshal Beresford had resumed his assault on the French right. The 4th division was clearly incapable of further offensive action and so Beresford replaced it with General Walker's 7th division. In his report to Wellington he wrote: "The severe loss the 4th division had sustained, and the mixture of its troops with each other that had unavoidably taken place in the hard contests it had had, induced me to direct it to halt and reform, and the 7th division to advance." [50] General Walker, after detaching his Portugese brigade to watch a French unit on the right, advanced forward with his two British brigades. There was heavy resistance from Taupin's division positioned just across the ravine and Walker probably only took his objective after the 6th regiment of foot had charged the French lines. In his report Walker wrote:to halt and reform, and the 7th division to advance."

"The 6th regiment ... was rapidly advanced to cover the formation of the 1st brigade at a point where the road, running over a narrow neck of the ridge (with ravines on each side), connected it with that on which the enemy were posted, and where our troops were consequently under the necessity of deploying under all the fire of the enemy; and I can hardly sufficiently praise the steadiness and gallantry with which the regiment performed this severe duty ... it was a considerable time before it was enabled to form, to move upon the enemy's line, which, however, it then immediately charged in a most gallant manner and drove them before it ..."

[51]

By this time Reille's position was no longer really tenable since the advance of the Light, 3rd and 6th divisions threatened to envelop his flank and rear. The retreat was ordered, Rouget's division and Paris' brigade withdrawing first. General Taupin and his division held out for slightly longer. Whether it was Walker's assault, or the realization that he was almost surrounded, it is impossible to say, but suddenly the French troops broke crying, "We are cut off! The enemy is on the road!" and hastily ran back through a deep ravine. [52] The first significant cracks had started to appear in Soult's defensive front.

What really sealed the outcome of the battle though was the sudden appearance of General Hill's troops on the French left flank. As described earlier, Hill had probably been instructed by Wellington to threaten Soult's left wing. It was not until eleven o'clock though that he received a direct order to cross the Gave de Pau. [53] One Portugese brigade attacked the broken bridge at Orthez, the other Portugese brigade demonstrated against the ford just above the bridge, while the British 2nd division planned to cross at the ford at Biron. This division met little French opposition, "... as the attention of the enemy was taken up with what was happening on their right", according to an officer's report on the action. [54] Within an hour virtually all of Hill's corps had safely forded the Gave de Pau. An officer from the 2nd division wrote in his memoirs:

"We soon reached the ford, above which was a thicket on the opposite bank, occupied by the enemy's tirailleurs, but not in great force, nor did they make much resistance. A battery of our Light Artillery galloped in front of the column to the edge of the ford, and opened in beautiful style, sending showers of grape whistling among them, and soon clearing them out. The Corps then rushed into the ford - five or six shells fell amidst us in crossing, but the water immediately extinguished them; and in the course of an hour, thirteen thousand men, with twenty guns, had passed without the slightest accident." [55]

The only French unit defending the Biron ford was the 115th line regiment, which totally outnumbered, was soon forced to retreat. Hill then pushed his troops northwards, in the direction of Sallespice on the Orthez - Sault de Navailles road. General Clausel, the French corps commander, tried to scrape together a defensive line from two battalions of conscripts, the 10th chasseurs a cheval and Baurot's brigade from Harispe's division. It soon became apparent however that Clausel was in danger of being cut off if the Allies reached Sallespisse and so he ordered Harispe to withdraw and evacuate the town of Orthez. Harispe retreated in reasonable order but he was still forced to abandon 3 guns. [56] The Portugese brigade opposite Orthez now moved across the bridge and through the town up the road to Sault de Navailles. [57]

Decisive

The decisive part of the battle had now been reached. All three French corps had been pushed back, Taupin's division of Reille's corps in some disorder. Soult's line was more or less intact but on his left Hill's corps was rapidly advancing towards Sallespisse. Moving to this part of the battlefield Soult saw that his right and centre risked being cut off and encircled if the Allies reached the bridge at Sault de Navailles. "I arrived at this moment on the left and saw that the army could not hold on in this position without being in jeopardy . . .", wrote Soult to Clarke after the battle. Soult then ordered a general retreat to Sault de Navailles and its wooden bridge over the Luy de Bearn. [58]

The French troops retired by echelons, from one line to another. The retreat was at first in good order, a fact admitted by Wellington in his report on the battle: "The enemy retired at first in admirable order, taking every advantage of the numerous good positions which the country afforded him." [59] Pressed hard by the Allies, who were now advancing on all fronts, and under some artillery fire, a degree of panic now began to set in among the French. News may have reached them that Hill's corps were now advancing down the same road to Sault de Navailles. The French troops accelerated their flight, heading for the safety of the bridge, which they reached at six o'clock in the evening. [60]

Many English sources speak in terms of the retreat becoming a rout at this point. Wellington himself wrote: "... the retreat at last became a flight, and the troops were in the utmost confusion." [61] This may have been exaggerated however, there is evidence that the French soldiers were more organized by the time they reached Sault de Navailles. Lapene for instance speaks of the French retreat continuing "with more order" at this point. [62]

Soult's army was now at its most vulnerable. Most of his soldiers were on the wrong side of the Luy de Bearn, in some disarray, with the Allied army close behind them. Yet in the end the vast majority managed to escape. Soult himself played a substantial part in restoring order out of this chaos. He rode to Sault de Navailles with his chief of staff and seeing the fleeing French troops there, ordered General Tirlet, commander of the artillery, to position 12 cannon on the heights north of the river. Several companies of pioneers were also placed on a wooded hillock on the same side of the river. The pioneer companies helped to serve as a rallying-point for the fleeing French troops and the artillery opened fire on the pursuing Allied cavalry, checking their advance. A breathing space gained, the French now had time to cross the Luy de Bearn by its wooden bridge or some adjacent fords. [63] Some 30000 men, almost 90% of Soult's original force, escaped in this manner. [64]

Soult was also saved by a rather ineffective Allied pursuit. The rapid advance, especially of Hill's detachment, led to a certain confusion and some opportunities were lost. The 71st Highland regiment, part of the 2nd division, allowed a group of French troops to pass by because they mistakenly thought that they were Spaniards! [65] The main failure though was in Wellington's use of his cavalry. It was true that the terrain at Orthez was not that suitable for horses, being "intersected by deep ditches and enormous enclosures", in the words of one of the cavalry commanders, Colonel Vivian. [66]

Yet Wellington had dispersed his three cavalry brigades, putting Vivian's on the extreme Allied left, Somerset's in the centre and Fane's on the far right with Hill's detachment. This meant that the cavalry was never able to concentrate and deliver a decisive blow to the French when they were at their most vulnerable, retreating towards the Luy de Bearn. Vivain's brigade was pinned down by French artillery fire for most of the day. "I was almost all day under a cannonade, but I kept my men under the hedges, hills & c., and so saved them," he wrote. [67]

General Fane's 13th and 14th Light Dragoons, part of Hill's detachment, did take part on the advance to Sault de Navailles but then came under French artillery fire and were ordered to retire. [68] Only in the centre of the battlefield did the British cavalry have any success, The 7th Hussars being able to make a charge.

Captain Thackwell of the nearby 15th Hussars witnessed what happened:

"Our brigade continued to advance, and on reaching the hill in front of Salles the French right wing was discovered retreating in the greatest confusion along the flats to the Luy de Bearn river. The 7th Hussars were ordered forward at a trot along the great road leading from Orthes to St. Sever; about two miles from Sault de Navailles they turned to the left and charged the enemy's rear-guard of infantry. It scarcely made any resistance and the 7th took 700 prisoners." [69]

The unfortunate French units that were attacked by the 7th Hussars were a battalion of National Guard and part of the 115th line infantry regiment from General Harispe's division. [70]

The final factor that helped Soult's army to escape was the time of year, for in late February it became dark roughly between six and seven p.m. (though this is only an educated estimate by the author, the sources omitting any times). Since the French troops did not reach the Luy de Bearn until 6p.m., as previously stated, there must have been only one hour at the most before it became fully dark. This would have enabled many French soldiers to slip away and seriously hindered any pursuit by cavalry. Both Wellington and Soult agree in their despatches that the pursuit ended after dusk. [71] Some English historians, Napier for instance, have argued that Wellington's injury also slowed down the pursuit, as he was unable to ride properly and so could not lead vigorously from the front. [72] Such a statement is only conjecture however, there is no direct evidence to support it, and Wellington never commented on this injury in his despatches to Bathurst.

With virtually all of his troops across the Luy de Bearn, Soult now fell back on the town of Hagetmau. Villatte's division and the cavalry formed the French rearguard, holding Sault de Navailles until 10 p.m., when they destroyed the wooden bridge and then withdrew themselves. Soult then retreated overnight towards the town of Saint- Sever, reaching it by the early morning of the 28th of February. [73] That day Wellington made some attempt to pursue the French columns, but it was relatively ineffectual. Soult's army was able to cross the bridge over the river Adour at Saint-Sever unmolested and so reach relative safety. The roads were poor, hindering Allied progress, [74] and virtually all of the Allied units had rested the night after the battle, thus giving the French, who had carried on retreating, a considerable head-start. [75]

Escape

Soult was thus able to make good his escape and live to fight another day. Wellington had to fight another battle against the French on the 10th of April, at Toulouse, and even then he did not destroy Soult's forces; they only capitulated on the 17th of April upon hearing the news of Napoleon's abdication.

Soult's army was certainly not destroyed at Orthez. It suffered only 11% casualties (as opposed to the Allies' 5%) [76] and, as described above, managed to regroup and fight Wellington again a month later. The battle thus cannot be described as a decisive Allied victory, more a tactical one. It did not close the campaign in the south of France in the same way that the Allied victory at Waterloo determined the outcome of another campaign a year later. Wellington certainly showed great strategic skill in manoeuvering his forces so that they were able to force the French back across the various river barriers in the area. In the conduct of the battle though, his touch was less certain. The initial attacks by Cole and Picton both failed, and Wellington was forced to alter his plans and concentrate more on the French centre with the 52nd regiment and the 3rd and 6th divisions.

Even then the decisive blow came about more by chance, through Hill's outflanking movement on the French right, a move that was ordered by Wellington at 11 a.m. before he redirected his other attacks. As the evidence has shown, it was this advance that threatened to cut off the French troops from their line of retreat over the Luy de Bearn and finally compelled Soult to order a withdrawal. The French retreat soon degenerated into a near rout, and Wellington must be critcised for failing to exploit this opportunity to destroy a sizeable proportion of Soult's army. Although it was late in the day, the Allied cavalry could have been used to devasting effect if only they had been properly concentrated. As we have seen though, this was not the case and a golden opportunity was lost. Even on the day after the battle Wellington might have caught up with the French rearguard if he had ordered his units to press on overnight instead of halting and making camp. Wellingon was often a cautious commander, and his success so far in the Peninsular had partly been a product of this attitude, but even so now was perhaps the time to be a bit more bold.

Soult also had a mixed battle. His decision to halt and make a stand at Orthez was probably a good one, taking advantage of the good defensive nature of the terrain. His conduct in the battle itself was rather passive though. Soult made no major counter-attacks, especially in the early stages when he might have profited from the failure of Cole's and Picton's assaults. Soult showed more resolution in the final stages of the battle, when he personally helped to rally many of his fleeing units. In the end though it was Wellington's irresolution that primarily saved him. One can say that Soult was very lucky to escape with what he did.

Three good books about Orthez have been written by English historians. The best in the author's estimation is Sir Charles Oman's, "A History of the Peninsular War", Vol. VII, (London 1930), which includes a very comprehensive chapter on the battle. Also useful is F.C. Beatson's, "Wellington, The Crossing of the Gaves and the Battle of Orthez", (London 1925), and one must not overlook Napier's, "History of the War in the Peninsular", Vol. VI, (London 1840), well worth reading despite its age. All three of these books have been recently reprinted and can be obtained through good booksellers. The reader who would like to study the French point of view can unfortunately only consult French-language works. Two worth studying are N.J.B Dumas', "Neuf Mois de Campagnes a la suite de Marechal Soult", (Paris 1907), and Vidal de la Blanche's, "L'Invasion dans le Midi", (Paris 1914). Both volumes are available in the British Library. For those wanting to read a good eye-witness account of Orthez the anonymous "Journal of an Officer in the Commissariat Department of the Army" is available in facsimile form. It is a particularly reliable record of the event as it was written only six years later in 1820.

The author would like to thank the staffs of the Bodleian Library, Oxford and the British Library for their help and assistance in finding material. The author is also grateful to Dr Chris Woolgar of the Hartley Library at the University of Southampton for allowing access to the Wellington papers and to the HMSO for giving permission to quote from them.

French Army (Commander Marshal Soult)

Corps Reille

Corps d'Erlon

Corps Clausel

Cavalry, (General Pierre Soult) approx 2000 men.

Artillery, 1500 men and 48 guns.

Grand Total 34000 and 48 guns. [77]

Allied Army (Commander Lord Wellington)

Cavalry (Stapleton Cotton)

Artillery 1162 men and 54 guns.

Grand Total 44061 and 54 guns. [78]

[1] Sir Charles Oman, "A History of the Peninsular War", (Oxford 1930), Vol. VII, p. 356-375 ; W.F.P. Napier, "History of the War in the Peninsula and the South of France", (London 1840), Vol. VI, p. 558-579.

|