Battle Of Saalfeld

10 October 1806

by Major AW Field, UK

| |

Of Napoleon's lightning campaign in Prussia in 1806 it is inevitably his crushing defeat of Hohenlohe at Jena, Davout's heroic destruction of the main Prussian army at Auerstädt and Murat's relentless pursuit that are best known.

Of course the fight at Saalfeld is not unknown, but the general impression is of a minor skirmish in which Prince Louis's outnumbered advance guard was swept aside by a greatly superior force and the unfortunate Prince killed in single combat by Quartermaster Sergeant Guindet of the 10th Hussars.

Whilst this perspective is understandable if only a general account of the campaign has been read, the battle was significant in two ways which were to leave an indelible mark the remainder of the campaign. The first was the superiority of the latest French tactics and the second was the establishment of a clear moral ascendancy which the victory gave the French in what was the first serious encounter of the war.

Taking what appears to our admittedly all seeing eyes to be a rather criminal lack of interest in the almost ritualistic destruction of the Austrian and Russian armies the previous year, Prussia plunged into war with France in the autumn of 1806. Since his victory at Austerlitz, Napoleon had had plenty of time to replace his losses and stood with nearly 200,000 men in Southern Germany. Even with their rather reluctant Saxon allies, the Prussians were able to field less than 150,000 men, and these were not suitably concentrated.

It is not my intention to give a detailed account of the campaign leading up to the battle at Saalfeld but a little background is required. Early in September Napoleon gave orders for the massing of his corps Arriving in Wurzburg on the 28th he concluded his orders for deployment by saying: "It is my intention to be at Saalfeld before the enemy can appear there in any considerable force". Although he had little knowledge of the Prussian deployment Napoleon had already decided to direct his famous battalion carre against the Prussian communications in order to force them into a battle in which he aimed to destroy their field army. He therefore imposed his will on the Duke of Brunswick commanding the main Prussian army and thereafter had him dancing to his own tune whilst a succession of Prussian councils of war were unable to agree on a coherent strategy of their own.

By the 5th October the French advance was well under way and if Napoleon was unsure of precisely where the bulk of the Prussian forces were, his own were well balanced to react quickly in any direction On the 9th part of Soult's corps brushed with the Prussians at Schleiz and easily pushed them back whilst Lannes and his Vth Corps reached Graffenthal, about 12 miles SW of Saalfeld On the same day Berthier sent the following orders to Lannes: "it is assumed that the enemy intends defending Saalfeld; if he is there with superior forces, you must not do anything until you are joined by Marshal Augereau. News about the enemy will be received during the day; if he has substantial forces at Saalfeld, the Emperor will march with 20,000 or 25,000 men during the night...But if the enemy has only 1 5,000 or 18,000 men, you must attack him after carefully studying his position; it being understood that Marshal Augereau's corps will by that time be with you"

Before he had received this order Lannes had written to Napoleon at 5pm on the same day " . . . Tomorrow , one hour after dawn, the whole army corps will be placed on the road to Saalfeld ... It has been a horrible day for the troops and artillery, with frightful roads and no resources ... It is impossible for Augereau to be here tomorrow, there being twelve endless leagues from Coburg to Graffenthal" Having received this correspondence from Lannes early in the morning of the 10th, Napoleon replied telling him to "urge M. Le Marechal Augereau to come on and you yourself immediately to attack Saalfeld"

Prince Louis Ferdinand commanded the advance guard of Hohenlohe corps of the Prussian army On the 9th October, after hearing that Lannes' corps had arrived at Graffenthal, he concentrated his division at Rudolstadt, about 10 miles NE of Saalfeld. He ordered Saalfeld to be occupied in order to deny it to the French on account of a depot of stores that was located there. In the morning of the 10th, having had early warning of the march of the French on that town, he set his division moving there via Schwarza By the time he got there at about 900 am cavalry outposts were already skirmishing in the woods beyond the town.

The Grande Armee that Napoleon led into Prussia was probably the finest he ever commanded: drilled to perfection whilst awaiting the abortive invasion of England and battle proven and hardened during the demolition of Austria. It is evident that morale was sky-high and all that was required was an opportunity to prove that they were the betters of an army with a proud and glorious tradition under Frederick the Great. The French Vth Corps consisted of two divisions; the first commanded by Suchet (one light and four line regiments for 11 fully formed battalions) and the second by Gazan (one light and two line regiments for 8 fully formed battalions). Only Suchet's division was destined to be engaged but it is interesting to note that all his regiments had fought at Austerlitz. The Corps cavalry brigade was commanded by Treillard and consisted of three light cavalry regiments (9 squadrons). It is estimated that no more than about 13,500 Frenchmen were involved in the fighting At the head of the Vth Corps rode Marshal Lannes about whom Napoleon wrote: "He was wise, cautious, bold in the presence of the enemy, imperturbably self-possessed. He had had little education. Nature had done everything for him.. He was better than all the generals of the French army on the battlefield in manoeuvring 25,000 infantry..."

Prince Louis Ferdinand commanded about 8300 men, although with various detachments no more than 7000 were actually engaged at Saalfeld. The Prussian army of 1806 was not as stuck in the past as many detractors may claim, but they were still some way behind the tactical sophistication being shown by the French at this time Still rigidly drilled and disciplined they were totally out manoeuvred on the battlefield and there was more to this than the fact that they were outnumbered. Throughout the campaign individual units fought gallantly, but with poor senior leadership and little formalised organisation at divisional level they were unable operate in a co-ordinated way that was capable of unhinging the flexibility of the French tactics. As can be seen from the order of battle the majority of Prince Louis's forces were actually Saxon. Saxony was only a half-hearted ally of Prussia and although her troops fought well their morale must be questioned. Prince Louis himself was a potentially formidable opponent: one of the leaders of the pro-war faction in the Prussian court he was enterprising and bold but lacking in experience in war; experience he was never to gain.

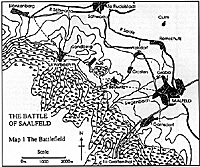

Large Map of Saalfeld 1806 (slow: 139K)

At about 2 miles to the West of the town are thickly wooded hills which rise a thousand feet above the town. It was through these steep hills that the road from Graffenthal ran before breaking into open ground overlooking Saalfeld. This open ground was dissected by a number of ravines, the biggest of which are the Siegenbach and another, unnamed, which ran from the hills to the Saale through the small villages of Beulwitz, Crosten and Wolsdorf. Both these ravines afforded excellent covered approaches for the skirmishers which the French were to use in profusion. A number of other small villages dotted the sloping ground and one or two areas of higher ground, such as the Sandberg, provided good observation and defensible positions.

Whilst Prince Louis marched on Saalfeld he left a detachment at Blankenberg covering his withdrawal route through Schwarza. This detachment consisted of the Pelet Fusilier Battalion, the Valentini Jäger Company, three squadrons of the Saxon Hussar Regiment and half of the Gause Horse Battery. They were destined to take no part in the coming battle.

Prince Louis arrived at Saalfeld about 9.00 am and formed his troops up in three lines: The first line had its flanks secured on the village of Crosten on the right and Saalfeld itself on the left. It appears that this line consisted of the Saxon regiments (each of two battalions) of Prince Clemens, Xavier and Kurprinz with the Prussian Muffling Regiment (also of two battalions) in the second line. The third line was composed of cavalry (Saxon and Prussian Hussars). The two Prussian Fusilier battalions (von Ruhle and von Rabenau), three squadrons of hussars and half a battery were deployed in front of Saalfeld facing the village of Garnsdorf

Prince Louis has been justly criticised for this position; not only was he formed up with an unfordable river only half a mile to his rear but he made little attempt to make the most of the natural and manmade obstacles and strongpoints that were available in the ravines and villages in the open ground between the hills and the river. His whole deployment was open to view by the French forces as they emerged from the defile, a dangerous exercise which was not to be seriously opposed by the Prussians

As we've heard, the cavalry outposts were already skirmishing as Prince Louis arrived on the battlefield at about 9.00am The French had left Graffenthal at 5.00am and had started arriving in the area of Saalfeld at the same time as the Prussians. Lannes' advance guard consisted of Treillard's cavalry brigade, one section of horse artillery (2 guns),an elite battalion (formed from the 8 elite companies of the four line regiments) and the two battalions of the 1 7th Legere. His main body consisted of the four Line Regiments and the Divisional Artillery, although it is interesting to note that there was no Sap between the two formations In his book "Principles of War" (see bibliography) Foch explains this apparently dangerous deployment by saying that "such an interval would have been useless in view of the range of arms. Once the advance guard should have closed up on its head, and the main body also closed up on its head, the commanding officer would have at his disposal a manoeuvre zone of 1500 or 1800 yards in which either to withdraw his forces or send them into action under shelter from enemy fire"

Cavalry patrols led Lannes' advance not only down the main Graffenthal-Saalfeld road but also along the numerous side roads and tracks that led through the hills into the Saale valley. They were closely followed by the elite battalion who were prepared to give the mounted patrols infantry support if required and also to seize any strategic points before they could be taken by the enemy. Operating in this way the Prussian outposts were quickly driven back onto the open ground which sloped down to the town. By 10.00 am Lannes himself was gazing down on the exposed Prussian positions. Given his excellent field of view and the lack of interference from the Prussians, Lannes now had plenty of time to make his plan as his forces came up.

Lannes could clearly see the weakness of the Prussian position and was keen to fix it in place before launching the decisive attack. Consequently he decided to use the elite battalion and the 17th Legere to seize the villages which were either weakly held or not held at all. By 11.00 am the elite battalion occupied Garnsdorf supported by two guns, the two battalions of the 17th Legere held Beulitz and two companies, which were all that existed of the 3rd battalion of the 17th, held the edge of the woods to the south of the point where the main track emerged from the hills.

Once these villages had been secured, swarms of skirmishers were deployed in the cover provided by the gardens and ravines These then moved forward and started harassing the formed ranks of the Saxons and Prussians. They also started spreading across the open ground connecting the French strong-points. Victor, Lannes' Chief of Staff, was to command at Garnsdorf, and Claparede, a brigade commander, was to command at Beulwitz. The light cavalry formed up near the edge of the woods between Beulwitz and Garnsdorf in order to move to the support of either if required.

With his advance guard now well established Lannes started to develop what was to be his main attack: a turning of the Prussians' right flank using Beulwitz as the pivot. This was the Prussians" weakest flank and would threaten their withdrawal route via Schwarza Towards this latter place Lannes sent a number of cavalry patrols which were able to reconnoitre and provide a measure of early warning of the approach of any Prussian reinforcements from the force in Blankenberg.

The French skirmishers now advanced into close contact with the Prussian line and making maximum use of cover caused increasingly serious casualties in the exposed Prussian ranks to which they seemed unable to reply. Crosten was occupied by the French who seem to have had little problem in pushing out the weak Prussian force who had garrisoned it. The effectiveness of the French tactics is well recorded by a Saxon engineer called Mumpfling, author of Vertraute Briefe: "Can you not see us all in line before that threatening rampart and lying unsheltered on the narrow stretch of meadows which separates it from the Saale, with our backs to the river? From that rampart, enemy skirmishers, themselves under perfect cover, could easily pick out any one of us, without it being possible to return fire on completely invisible men; and this pastime lasted for several hours"

By 1.00pm the majority of Suchet's division was now available and making their way through the woods northwards towards the Prussian right flank. Seeing an increasingly formidable number of the enemy entering the field, and facing mounting casualties caused by the French skirmishers, Prince Louis now faced the dilemma of having to weaken his centre in order to secure his withdrawal route via Schwarza. As if this was not bad enough, he had earlier received a message from Prince Hohenlohe ordering him to stay at Rudolstadt and not to attack! The Prince had no alternative but to guard the road to Schwarza: the second battalion of the Muffling infantry regiment was sent back to that town whilst the first battalion and a foot battery was sent to occupy the Sandberg feature.

The Prince Clement Regiment was ordered to establish its first battalion between the villages of Aue and Crosten, in order to connect the occupation of the Sandberg to the main body. The second battalion was to climb the Sandberg where it was to place itself to the right of the battery and battalion of the Muffling Regiment. Out of his ten battalions Prince Louis now had two defending Saalfeld and four securing his withdrawal route, each supported by a battery; thus in his "main body" he was left with only the four battalions of the Xavier and Kurprinz Regiments, half a horse battery and seven squadrons of hussars.

The growing concern and consequent uncertainty of Prince Louis at this time can be well imagined. However, believing his right and rear to be secure he decided to attack. Whether this was an act of bravado or an attempt to win some time to effect an orderly withdrawal in order to comply with Hohenlohe's instructions to remain at Rudolstadt we do not know. However, without the means to prepare the attack properly, with the French skirmishers dominating the battlefield and with the superior numbers of the French the result was almost a foregone conclusion. The two Saxon regiments were formed into battalion squares en echiquier and sent forward with their right on the ravine that joined Beulwitz to Crosten. Given that this was occupied by the French skirmishers it must have been a harrowing experience for the Saxon troops. When they came level with Beulwitz the fire from their flank became so heavy that they stopped to return it. Becoming increasingly disordered by the French fire and facing superior numbers the Xavier Regiment started to retire, followed by that of the Kurprinz. Their withdrawal was followed by the 17th Legere who occupied Crosten; but the Saxons reformed and pushed them out again.

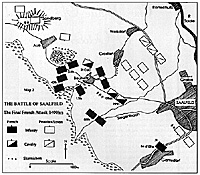

Having easily repulsed the Saxon attack it was now time for Lannes to execute his planned decisive counter-move. He had the whole of Suchet's division poised; the elite battalion would continue to tie down the forces in front of the town and the 17th Legere who had been most heavily involved in the fighting so far passed into reserve with the 88th de Ligne. His plan was for Reille's brigade (34th and 40th de Ligne) to attack Aue and the Sandberg which would secure the flank of the main attack which would be delivered by the 64th de Ligne of Vedel's brigade and the light cavalry brigade. The attack would be prepared by the divisional artillery (see Map 2).

Large Map of Saalfeld 1806: 2 pm (slow: 114K)

The three battalions of the 34th formed the first line whose objective was the village of Aue itself, whilst the two battalions of the 40th marched in echelon to the left rear in order to protect the left flank of this attack and then assault the Sandberg once Aue was secured. These attacks were entirely successful; the Prussian battery was captured and the infantry thrown back towards Schwarza.

Whilst this attack was going on, more of the divisional artillery came up and started to soften up the Prussian centre ready for the decisive attack The 64th de Ligne moved forward at about 3.00pm with the 21st Chasseurs a Cheval to its left and the 9th and 10th Hussars to the right The 17th Legere and 88th de Ligne formed the second line and the 34th, fresh from its success at Aue, protected the left flank. In the race of this co-ordinated attack the four already shaken Saxon battalions were soon put to flight This presented the French cavalry with the opportunity they were waiting for and they plunged into the retreating mass of white coated infantry.

Prince Louis, seeing the defeat of his infantry, put himself at the head of five squadrons of his own cavalry in front of Wolsdorf and charged the French hussars in an effort to retrieve the situation. Despite an initial success the Prussian cavalry were slowly pushed back and Prince Louis found himself engaged in hand-to-hand combat with a sergeant of the 10th Hussars called Guindet. Guindet called on the Prince to surrender but in reply he gave the French hussar a wound to the face; Guindet ran him through the body and he fell dead.

(In the Second Bulletin of the Grande Armee Napoleon reported: "One can say that the first blows of the war have killed one of its instigators")

The Prussian defeat was complete. Faced by an overwhelming attack and with their commander dead the Prussian force dissolved into small groups which were to make their withdrawal as best they could. Some fled over the bridge in Saalfeld, some made for Schwarza and some sought to join the small force at Blankenberg. It could not have been an easy move; the French cavalry roamed the open ground attacking those who did not surrender and the infantry pushed on to attack Schwarza, where the battalion of the Muffling Regiment was dispersed, and Blankenberg where the garrison made a fighting withdrawal towards Rudolstadt. The pursuit by the French cavalry was relentless and continued to the bridge at that town.

The French claimed to have taken fifteen hundred prisoners, four flags, twenty five guns and two howitzers. There is no record of the Prussian and Saxon losses, although they must have been considerable. Suchet puts his own losses at only 172.

Putting aside Lannes' s superiority of numbers, he had fought the perfect battle: he had found the enemy with his cavalry patrols, fixed him with an advanced guard deployed almost entirely as skirmishers, struck him with an overwhelming force at the decisive point and then pursued him relentlessly with his cavalry.

On the other hand, Prince Louis had also been the architect of his own defeat; he chose a dangerous position with a river directly to his rear (just as the Russians were to do at Friedland with similar results), deployed all his troops in the open ground which exposed them to enemy fire and denied them the benefit of defending strong points (a force multiplier), spread his troops too thinly across a wide front denying himself a defence in depth or a viable reserve and then committed himself to an attack against overwhelming numbers

As I pointed out in my opening remarks this small battle was a taste of what was to come for the Prussians; despite no shortage of bravery, the failings of poor leadership and outdated tactical doctrine were to lead to disaster at Jena and Auerstädt just four days later.

The Principles of War. Marshal Foch. Chapman & Hall, London, 1918.

Whatever may be said about the inadequacies of the Prussian army of 1806 and their failure to appreciate the impact of the new type of warfare that Napoleon and his army waged, at least they were prepared to face up to the new realities in the light of their devastating defeat. The following passage is reproduced from Foch's Principles of War which shows to what extent the Prussians (and probably all the Allies) based their later tactics on those used by the French. In the context of the action at Saalfeld, it virtually sums up the way the French operated in this battle.

|

The small town of Saalfeld stands mainly on the left bank of the River Saale where the river runs SE to NW.

The small town of Saalfeld stands mainly on the left bank of the River Saale where the river runs SE to NW.

At about 2.00pm, covered by the inevitable cloud of skirmishers, Reille's brigade stepped off towards Aue.

At about 2.00pm, covered by the inevitable cloud of skirmishers, Reille's brigade stepped off towards Aue.