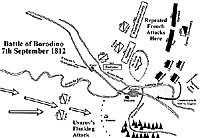

When one talks about the Battle of Borodino in 1812, one nearly always concentrates on the main events of that memorable day; the taking of the fleches, the storming of the Great Redoubt or the cavalry battles. One may even consider and discuss Davout's plan for a flanking manoeuvre, a manoeuvre Napoleon rejected in favour of a more costly, and as it turned out, indecisive frontal attack. But one seldom, if one is honest, discusses another flanking manoeuvre, namely that of General F.P. Uvarov's Ist Cavalry Corps. This manoeuvre, as it turned out, probably had more effect upon the outcome of the battle then its apparent failure suggests.

As everyone knows Napoleon had invaded Russia in June 1812 to bring the Russians back into line with his continental system, which denied British goods access to European markets. His plan was to use his favourite strategic manoeuvre, envelopment, to bring the Russian Armies to battle within a matter of weeks. Unfortunately this good plan failed repeatedly as the wily Russians managed to slip out of his envelopments on a number of occasions and Napoleon found himself drawn deeper into Russia in search of the desired battle.

It nearly occurred at Smolensk but the Russians again retired at the last moment and Napoleon was tempted to call the campaign off and rest through the winter at Smolensk, it would have been a wise move. But Napoleon's egotism got the better of him and he pursued the Russians further and finally caught up with them in a prepared position at the village of Borodino. At last the longed for battle had arrived and Napoleon for one did not doubt the outcome.

Large Map (64K)

Though this is hardly surprising, given the frontal nature of the French attacks and the lack of tactical subtleties displayed by the French command.

The day began well enough though with the successful capture of the village of Borodino by General Delzons' division of infantry. There then followed the struggle for the Fleches and the village of Semyonovskaya, a touch and go affair for most of the morning, as well as preparations for the great assault upon General Raevski's Great Redoubt (the principle event of the day and most well known attack of the battle).

That same morning, Hetman Platov and his Cossacks had been employed to find a crossing over the Kolotscha river on the Russian right and had been rather surprised to learn the French left wing was protected by only a light line of Bavarian Chevau-legers. Immediately realising the possibilities such a find offered, Platov despatched an officer to General Kutusov, the Russian Commander-in-chief, with the suggestion that a flanking manoeuvre against the French left be attempted. On the way to Kutusov the officer encountered Colonel Toll and convinced that officer of value of such an attack, Colonel Toll was Kutusov's Quarter-master General and it was he who put the proposal to Kutusov.

Attack Position

Crossing a ford near the village of Starnoie, Uvarov did not reach his attack position until 11 or 12.00am, some three hours after receiving his initial orders. There he found himself opposed by d'0rnano's Bavarian Chevaulegers, who had been cannoned all morning and were far from steady. Attacking quickly, Uvarov's Guard cavalry made short work of the dispirited Bavarians and chased them over the Woina stream but were then bought to a halt by General Delzon's infantry division, which held the village of Borodino. Deploying the 8th Legere, 84th and 92nd Ligne infantry regiments in square, Delzons fought off a series of charges that Uvarov's Guard Hussars made but then had to endure the fire of Uvarov's artillery.

Meanwhile, Platov's Cossacks came up in support of Uvarov and occupied the Lacharisha wood to Delzons' left, destroying two voltigeur companies that had been sent there. Platov's Cossacks then began a series of attacks from the safety of the Lacharisha wood and joined by their brethren, the Cossacks of the Guard, soon began picking off isolated elements of Delzons' division, most notably his artillery support. Colonel Achouard of the Italian artillery is killed and two of his guns are taken and Uvarov, sensing victory, renews the attacks of his own cavalry but Eugene, Delzons' Commander-in-chief, has recognised the danger posed by Uvarov's attack and is marching to Delzons relief.

Marching at the head of his Italian Guard, who had just been about to join in the attack on the Great Redoubt, Eugene arrives just in time as Delzons' regiments are about to be overwhelmed. Unleashing the now rallied Bavarian Chevau-legers, supported by the Italian Guard Dragoons and the Guardia d'0nore, Uvarov's valiant but now exhausted cavalry are in their turn chased back across the Woina stream. The Italian Guard relieving Delzons' exhausted division and recapturing all the ground lost to Uvarov's incursion. It was about 3.00pm. Losses on both sides were light but Uvarov's manoeuvre had failed, largely because Delzons had held his ground whilst Eugene had marched to his assistance with the Italian Guard. But the attack had had an impact on the battle that made it a movement of some significance.

News

For news of the attack had reached Napoleon's Headquarters at a critical stage of the battle, when Napoleon was receiving countless requests from his generals to send in the Imperial Guard and win the battle. But the news of Uvarov's attack and the fact that some of Platov's more adventurous Cossacks were already reaching the outposts of the Imperial Guard, seems to have convinced Napoleon of the need to conserve his reserves to meet the unexpected and leave the winning of the battle to his line formations.

Thus, Uvarov's flanking manoeuvre had a significant impact on the battle beyond the limited casualties it inflicted on the French. Firstly, as we have seen, it forced Eugene to divert his attention from the assault on the Great Redoubt to the stabilising of his flank, and secondly, it give Napoleon an excuse, indeed it may have helped to persuade him, not to commit his Imperial Guards to battle. The net result of this development was that the Russians were able to stabilise their front after the fall of the Great Redoubt. Had the French Imperial Guard been committed at that moment then there is little doubt that the Russian Army, exhausted and battered as it was, most have broken under the pressure and Napoleon would have had his decisive victory.

Like, the Prussian attack on Plancenoit three years later, Uvarov's attack distracted Napoleon's attention from the main event and led to his hesitation in committing the Guard. The resulting lost time enabling his opponent, Kutusov at Borodino and Wellington at Mont St. Jean, to stabilise their front to meet the next attack. And though Napoleon was ultimately successful at Borodino, primarily because Kutusov abandoned the field it must be said, at Mont St. Jean he would lose the battle because of a moment of hesitation when he let the decisive moment slip from his grasp.

Therefore, far from being an insignificant element in the great holocaust that was the Battle of Borodino, Uvarov's flanking manoeuvre had profound influence upon the course of the battle and probably saved the Russian Army from a decisive defeat that may well have changed the subsequent course of Napoleon's 1812 campaign. To paraphrase the words of Wellington, it is sometimes the little events that make victory possible but it is not always possible to know when these events occur. Uvarov's attack was a small event, undoubtedly, it did not win the battle, undoubtedly, but it did influence a key decision or two and this in turn seems to have saved the warriors of Holy Russia from another Friedland.

Austin, Paul Britten, 1812 The March on Moscow (London: Greenhill Books, 1993).

The day of Borodino, 7th September 1812, would herald a few surprises for Napoleon, the most important of which was the indecisive nature of the engagement.

The day of Borodino, 7th September 1812, would herald a few surprises for Napoleon, the most important of which was the indecisive nature of the engagement.

Jumbo Map (slow: 131K)

Toll proposed that General Uvarov's 1st Cavalry Corps, which consisted of 2,500 cavalrymen of the Russian Guard and had hitherto stood idle on the Russian right, should advance to fall on the French left and rear. To this, Kutusov replied disinterestedly: "C'est bon, prenez le!" And hence at about 8 or 9.00am the manoeuvre was decided upon and implemented but it would be some time before Uvarov was in position, having to turnabout and then cross the Kolotscha to support Platov's Cossacks, about 2,000 strong, making altogether about 4,500 men and 12 guns in the flanking manoeuvre.

Toll proposed that General Uvarov's 1st Cavalry Corps, which consisted of 2,500 cavalrymen of the Russian Guard and had hitherto stood idle on the Russian right, should advance to fall on the French left and rear. To this, Kutusov replied disinterestedly: "C'est bon, prenez le!" And hence at about 8 or 9.00am the manoeuvre was decided upon and implemented but it would be some time before Uvarov was in position, having to turnabout and then cross the Kolotscha to support Platov's Cossacks, about 2,000 strong, making altogether about 4,500 men and 12 guns in the flanking manoeuvre.

Sources and Further Reading

Chandler, David G., The Campaigns of Napoleon (New York: Macmillian, 1966. Reprint London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1987).

Chandler, David G., The Illustrated Napoleon (London: Greenhill Books, 1991).

Clausewitz, Carl von, The Campaign of 1812 in Russia (First English Edition

published in 1843. This edition London: Greenhill Books, 1992).

Esposito, Vincent J., and Elting, John R., A Military History and Atlas of the Napoleonic Wars (New York: Praeger, 1968. Reprint London: Arms and Armour Press, 1980).

Nicolson, Nigel, Napoleon: 1812 (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1985).

Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #39

Back to First Empire List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1998 by First Empire.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com