The Battle of Göhrde

16 September 1813

by John Salmon, UK

| |

A very obscure action in the German War of Liberation against Napoleonic occupation or a researcher's valiant but futile attempts to find some background material.

'Lets just pop up the stairs and look at the first floor gallery,' insisted my wife.

I have lost count of the number of times Elizabeth has been dragged uncomplaining around Waterloo museums so how could I refuse. Up the stairs we climb, through an archway and WOW! Feet and coffee are forgotten in an instance. There on the wall was one of the biggest paintings of a Napoleonic battle I have ever seen. It seemed to fill the wall, dimensions are not my strong point but at a guess it was at least 60 ft long by 25 ft high. On the right are red jacketed infantry with funny white Shakos being led in a charge by a similarly uniformed officer who looks like he is stepping over a badly wounded soldier. With them are black uniformed infantry. An officer on horseback in dark green strikes a dramatic pose, another wounded on the ground holds up his arm in a cry for help. They are attacking what looks like a brown coated mob who are only interested in surrender or escape. In the background can be seen other infantry attacks and a cavalry charge.

A scan round the room for other information revealed a stained glass window with a heraldic crest, the lion and unicorn supporting the royal standard of a royal family. On the wall opposite was a list of battle honours in the shape of a cross. It was a list that any British army regiment would have been proud of. I immediately recognised the names of Blenheim, Ramillies, Oudenarde and Malplaquet as battles from the War of the Spanish Succession (1701 - 1714). Dettingen and Minden also struck a cord. Then the familiar names of the Spanish Peninsular War can into view, Talavera, Barossa, Garcia Hernandez, when my eyes fell upon Waterloo it was like seeing an old friend. Turning back to the painting I looked for more clues as to what it represented. I guessed that red coated soldiers must be Hannoverians, we were after all in the middle of what was the Grand Duchy of Hannover, Celle was the ducal seat before its transfer to Hannover in the early part of the 18th century. Red uniforms could easily have been supplied by Britain, the connection being that Britain's King George III was also the Duke of Hannover. The connection was severed in 1837 when Victoria came to the British throne, the Hannoverian succession could only pass through the male line. The black uniforms could be Prussian's and the green might be Jager battalions of the Kings German Legion (KGL). The enemy being attacked must be French but the brown coats puzzled me. Then I remembered seeing numerous French infantry at the 1995 Waterloo Re-Enactment clothed in similar coats to keep their nice blue uniforms clean.

If this battle was late on in the Napoleonic wars then perhaps the French were equipping their soldiers on the cheap. But still I had no real clue as to what, where or when the battle depicted was.

Salvation came, as often it does, from my wife who had picked up a leaflet unfortunately it was in German, fortunately Elizabeth speaks the language. We sat down and she read the story of the painting to me. What follows is her translation of the museums leaflet.

'What is depicted in the battle by the painter Carl Röchling is not only of regional meaning for the Hannover region, but also plays an undoubted role within the War of Independence against Napoleonic occupation.

Napoleon dominated almost the whole of the European mainland at the beginning of the 19th century. The German middle states were united under him in the Confederation of the Rhine. In 1807 the Prussians [still fighting under the influence of Frederick the Great], collapsed under Napoleon's attack.

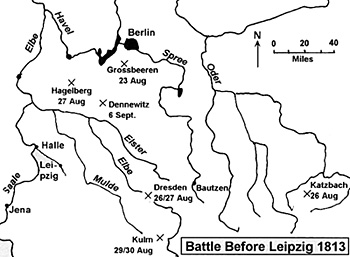

After the failure of Napoleon's Russian Campaign [1812], a new wave of opposition came against the occupiers. The Prussians formed a coalition with Russia, who had joined with Austrian and Sweden. Under Metternich's mediation, there was a truce from June to August 1813. During this time, allied armies [were] recruited, whose goal was to encircle Napoleon. In quick succession engagements and battles were fought mostly with success by the allies, (for example; Grossbeeren, Katzbach-Wahlsatt, Dresden-Kulm, Tauentzien).

The picture of Röchling's shows the moment when shortly before sunset, the Hannoverian Brigade under [Sir Hugh] Halkett overran with a bayonet attack the French [who] were beaten into flight. On the far right can be seen the black uniforms of the Lützower Jager, who did not actually participate in this attack. Next to them are the field battalion of Bennigsen with red coats and white Shakos. High on a charger the Brigade commander, Sir Hugh Halkett, is depicted in the green uniform of the 2nd Light Battalion of the Legion [KGL], behind him is Lt. Colonel von Bennigsen, left are the fleeing French in their light brown hooded cloaks - on the ground - badly wounded - cavalryman von Hugo from the 3rd Hussars of the King's German Legion who rode from the flank for a second charge.' [1]

Some of my questions had been answered but many more had been raised. Upon returning home the contents of my Napoleonic library were ransacked for references to the battle. The battles listed, Grossbeeren, Katzbach-Wahlsatt, Dresden-Kulm, Tauentzien, are with the exception of Dresden-Kulm almost as obscure as Göhrde. Chandler's Dictionary of the Napoleonic Wars mentions Grossbeeren (page 185) and Katzbach (page 222), Dresden is of course mentioned (page 124), but it is only by the museum linking it to Vandamm's surrender of his corps at Kulm (page 227) that you could possibly say it turned out to the allies advantage. [2] Tauentzien is not mentioned in any of my sources, they are as silent about it as they are on Göhrde. About the battle itself I found precisely nothing. If Chandler's Dictionary does not mention it then I thought it must be pretty obscure, this was not going to be easy.

I did however manage to pick out a few bits of material on some of the information in the museum leaflet. The white shakos of the Hannoverian infantry where explained by Peter Hofschroer in his Osprey book on the Hannoverian army, 'Battalion Bennigsen was issued with white 'Belgic' shakos manufactured for the British Army in India!' [3] Sounds like the British government was also equipping its soldiers and allies on the cheap. Chandler's Dictionary lists a General Sir Colin Halkett who commanded the 2nd battalion of the King's German Legion (KGL) and a brigade at Waterloo [4]. The Sir Hugh Halkett mentioned in the painting is presumably his brother, which I bet leads to lots of confusion.

But why fight a battle at Göhrde at all? Chandler in Napoleon's Marshals' states that when hostilities were renewed after the summer truce in August 1813 ' Davout, who Napoleon had instructed to hold Hamburg with XIII corps was 'ordered to aid Oudinot and the northern group of corps in an onslaught designed to take Berlin'. [5]

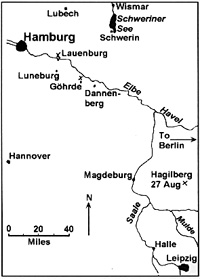

His forces had progressed well, pushing back the allies at Lauenbourg south east of Hamburg and advancing on Wismar and Schwein (or Schwerin) east of Lübeck near the Baltic coast. The onslaught however failed when Oudinot lost at Grossbeeren just south of Berlin on 23rd August as did Girard at Hagelberg on the 27th August. Napoleon won at Dresden on 26 - 27th August but any benefits were lost when Vandamm was forced to surrender at Kulm on 29 - 30 August. Ney also lost at Dennewitz on September 6th. After these setbacks Napoleon regrouped his forces around Leipzig. This left Davout isolated in Northern Germany.

So far so good, the following bit though is I admit all conjecture on my part, but I hope it gives a reasoned clue as to why the battle was fought. If Davout was to assist in a drive on Berlin then he would have to push a force down the Elbe in an effort to make contact with Girard at Magdeburg or possibly reinforce him. But after Ney's defeat at Dennewitz Napoleon had abandoned his onslaught on Berlin. It follows that with the Berlin attack abandoned Davout would want to recall his forces to the Hamburg area, this is what he did with the forces at Wismar and Schwein.

The museum leaflet could well be stretching things a bit far when it states that the allied victory at Göhrde meant that 'the union between Marshall Davout's corps and the Grand Armee under Napoleon was stopped.' I think that Davout had already pulled back to Hamburg in anticipation of a long siege, which is what happened.

A conversation with First Empire's editor stirred his memory about a reference to the battle in F. Loraine Petre's Napoleon's Last Campaign in Germany, 1813. He is not just a pretty face you know, come to think of it he is not a pretty face, (joke, honest), but he had given me another possible source of information. As luck would have it Petre's book on the 1813 campagn is the only one not in my collection, (I'll be on the lookout for one at next years Napoleonic Fair). Salvation again came from my wife who has lending rights at Cambridge University Library and was able to obtain a copy. A quick dive into the index, alas no mention of Göhrde. But wait there is a Görda, a flick through the pages revelled the following extract.

'On the 16th September a raid of Walmoden's troops crossing the Elbe destroyed a detachment of Davouts corps at Görda. This detachment was on its way to Magdeburg.' [7]

Right date, right area, this was more than a coincidence. Görda must be another name for the battle. Back to the other sources to check if it mentioned, unfortunately it is not. Walmoden however was a Swedish General so was presumably came under Charles (or Carl) John, Crown Prince of Sweden and Commander of the Army of the North. The Crown Prince was of course better known as Jean Bernadotte, former French Marshal who's performance in the coming campagn would leave many questions over his motives.

Those three brief lines are all I could find about the battle. Action would seem to be a better description of the event. I have no tactical details on the battle save what is mentioned in the museum leaflet. But even the leaflet admits that the scene on the far right of the painting concerning the black uniformed Lützower Jagers is not accurate, as it says they 'did not actually participate in this attack'. Who were the Lützower Jagers and why are they in the painting? Petre supplies part of the answer, they were a 'Free Corps', nominally part of the Prussian forces.

'These free corps consisted largely of foreigners, were of very varied constitution, not always either well led or well disciplined, and, altogether, not so importuned as they might have been.' [8]

Returning to the leaflet revelled another passage which my wife's mother, another German speaker, translated. What a blessing it is to speak another language, and an even greater blessing to have willing translators available when you cannot. Many thanks to my wife and mother-in-law.

The picture was presented by order of Emperor Wilhelm II at the time of the settlement of a conflict between the Hohenzollerns and the Welfen. [Hohenzollern is the Prussian royal family, Welfen were presumably Hannoverian] It was the political aim of the Kaiser [Emperor] to reconcile both groups.

Since the painting was expressly to represent the Hannoverian - Prussian comrades - in - arms, the military were picked out separately for the theme in the Göhrde, in the course of which the Prussians had taken part. [Even if it was not in the attack depicted].

Following a rough draft by the Reitzenstein Barons, the picture was finished in the first instance by the Hannoverian painter Ernst Pasqual Jordan (1858 - 1924). Jordan's rough copy showed however (according to historical fact) that there was no representation in the battle of the Prussians who had taken part. Jordan's rough draft was declined on political grounds, and the Berlin military, battle and genre painter Carl Röchling (1855 - 1925) was commissioned with the execution of the painting. As a concession to the patron [Kaiser Wilhelm] the painting was freely expressed with the added inclusion of black - uniformed riflemen of the Lützower volunteer force.' [9]

The French used to say of Napoleon that nothing lied like one of his bulletins, well he was not the only Emperor that would bend the truth to suit his needs. The painting, dramatic as it is, takes a certain amount of artistic licence with the truth. Political requirements in the German Empire at the beginning of the 20th century meant that a painting of a battle which had taken place a century earlier, at a time of perceived German unity, was deliberately falsified. A ready supply of salt is needed by any researcher when examining paintings, accounts of battles or any other historical record, no matter when they are written. Unless the painting or document is put into the correct context and the belief system of its author are understood, then the innocent researcher is liable to be sent off on a false trail with unfortunate consequences.

Some things can though be discerned from the text of the leaflet. The phraseology is interesting, in the first paragraph the term 'War of Independence against Napoleonic occupation,' is used. This evokes an image of a people striving to throw off the yoke of foreign occupation and tyranny. Just as the French today speak of the German 'occupation' in the Second World War so some north Germans spoke of the French occupation in 1806/13, which is perhaps what the writer is trying to convey.

The French revolutionary and Napoleonic wars introduced the concept of Nationalism and changed the German map. Napoleon, after victories at Jena-Auerstadt, in 1806, viewed Germany as a field to be harvested for money, and men for his armies. To facilitate this he overhauled and radically altered the states that made up Germany. He swept away the host of small territories and replaced them with nine states making up the Confederation of the Rhine. Saxony and Bavaria were enlarged and Prussia was forced to give up large areas in the west, France moved its border to the Rhine.

The concept of Nationalism introduced by the French took root in Germany, but especially in Prussia which was forced to accept a humiliating and expensive peace at Tilsit in 1807. Reformers such as Sharnhorst, Gneisenau and Clausewitz changed the army into one of national conscription. The concept of the Nation in Arms was used by the Prussians to rouse Germany against the foreign invader; this army fought for National Liberation following Napoleon's disastrous 1812 campagn. To fight the French on their terms required something more than a call to defend the kings or dukes lands. They needed something more, to quote Gneisenau, Bluchers chief of staff at Waterloo and one of Prussia's leading reformers, they would have; '... to give the People a Fatherland if they are to defend that Fatherland effectively'. [10]

To defeat the political ideals of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Nation State the soldiers of the Prussian and German armies would have to believe in a concept greater than their king, duke or his state. Michael Howard stated it thus; 'Was it not rather a broader, noble concept: Germany?' [11]

For the French, the political ideals generated by the revolution and Napoleon, the nation as the foundation of the state, a mass conscript army as the embodiment of the nation in arms, were to live on in the myths and symbolism of the nation. Similarly the concept of the German nation, used as a counter to the nationalism of France, became part of the dream of a united Germany for many intellectuals and politicians. A dream that would become reality when Prussia led the German states to a crushing victory over a France led by Napoleons nephew in 1870/71. In that war and latter in 1914/18 and 1939/45 France would rue the days she helped give birth to German Nationalism.

The painting 'The Battle of Göhrde 16 September 1813' that my wife and I stumbled across in Celle is, besides being an exciting if not totally accurate depiction of Napoleonic warfare, an expression of that Nationalism.

David Chandler, Dictionary of the Napoleonic Wars, London, Greenhill Books, 1993.

Any ideas out there on where I could find any further information on this battle would be gratefully received.

[1] Die Ehrenhalle, Heraugeber; Bomann-Museum, Celle, Text und Gestaltung: Juliane

Multiple Letters to Editor about Göhrde.

|

You never know when a piece of Napoleonic history will pop up before you. In September of 1997 my wife Elizabeth and myself were touring round northern Germany. On this particular day we were looking around the picturesque city of Celle, which is about 20 km north west of Hannover. Having dragged my wife around more battlefields than she cares to remember it was her turn to drag me around yet another 'Volks' Museum. In this case the Bomann Museum in Celle. After seeing numerous displays of farm machinery, kitchens and various other fascinating bits and bobs my feet were hurting and I was about ready to call for a cappuccino break.

You never know when a piece of Napoleonic history will pop up before you. In September of 1997 my wife Elizabeth and myself were touring round northern Germany. On this particular day we were looking around the picturesque city of Celle, which is about 20 km north west of Hannover. Having dragged my wife around more battlefields than she cares to remember it was her turn to drag me around yet another 'Volks' Museum. In this case the Bomann Museum in Celle. After seeing numerous displays of farm machinery, kitchens and various other fascinating bits and bobs my feet were hurting and I was about ready to call for a cappuccino break.

On the 16th September 1813, the allies - Hannoverians, Russians, Britons, Prussians, Hansa and 'Kings German Legion' came to Göhrde, about 20 km west of Dannenberg, [See map], defeated French troops and drove them away from the bank of the Elbe. Through this, a month before the battle of Leipzig, the union between Marshall Davout's corps and the Grand Armee under Napoleon was stopped.

On the 16th September 1813, the allies - Hannoverians, Russians, Britons, Prussians, Hansa and 'Kings German Legion' came to Göhrde, about 20 km west of Dannenberg, [See map], defeated French troops and drove them away from the bank of the Elbe. Through this, a month before the battle of Leipzig, the union between Marshall Davout's corps and the Grand Armee under Napoleon was stopped.

Hofschroer's 'Leipzig 1813' in the Osprey Campaign series is a good background to events but Gohrde is not mentioned. It did occur to me that the battle may be known by another name, just as Ratisbon of 1809 fame is now modern Regensburg, but I could find no clues. In desperation I turned to a map of Germany to try and find where Göhrde is. Finding it on the map is difficult, but by concentrating on the Elbe between Hamburg and Magdeburg I managed to discover the elusive location. It is south east of Hamburg, on the road between Luneburg and Dannenburg, the Elbe river is close by, (See attached map).

Hofschroer's 'Leipzig 1813' in the Osprey Campaign series is a good background to events but Gohrde is not mentioned. It did occur to me that the battle may be known by another name, just as Ratisbon of 1809 fame is now modern Regensburg, but I could find no clues. In desperation I turned to a map of Germany to try and find where Göhrde is. Finding it on the map is difficult, but by concentrating on the Elbe between Hamburg and Magdeburg I managed to discover the elusive location. It is south east of Hamburg, on the road between Luneburg and Dannenburg, the Elbe river is close by, (See attached map).

The Magdeburg reinforcements were now out on their own in the middle of hostile territory. That it was hostile can be demonstrated by the numerous allied raiding parties criss crossing the north German plain, these were not just pin prick attacks. A Russian called Czernitchew, with 2300 Cossack cavalry and 6 guns forced Cassel to surrender on the 28th September. [6] The lack of cavalry after the Russian disaster could only exacerbate French vulnerability to this type of raid. If the small French force were unaware of the trouble brewing around them, and with cavalry recognisance limited it might well be, they could easily blunder into one of the larger allied forces. Which is what I suspect happened. Shades of their experiences of being cut off in the Spanish Peninsula by the guerrillas must have passed through a few experienced soldiers thoughts.

The Magdeburg reinforcements were now out on their own in the middle of hostile territory. That it was hostile can be demonstrated by the numerous allied raiding parties criss crossing the north German plain, these were not just pin prick attacks. A Russian called Czernitchew, with 2300 Cossack cavalry and 6 guns forced Cassel to surrender on the 28th September. [6] The lack of cavalry after the Russian disaster could only exacerbate French vulnerability to this type of raid. If the small French force were unaware of the trouble brewing around them, and with cavalry recognisance limited it might well be, they could easily blunder into one of the larger allied forces. Which is what I suspect happened. Shades of their experiences of being cut off in the Spanish Peninsula by the guerrillas must have passed through a few experienced soldiers thoughts.

The history of the origin of the painting, the choice of theme as well as the form of the picture are closely connected with the political situation in the Empire at the beginning of the century. [The German Empire and the 20th century].

The history of the origin of the painting, the choice of theme as well as the form of the picture are closely connected with the political situation in the Empire at the beginning of the century. [The German Empire and the 20th century].