Betrayal or Patriotism?

Marmont in 1814

by Patrick E. Wilson, UK

| |

And yet, does Marmont deserve this label? Do Marmont's actions in the spring of 1814 reveal a traitor or a patriot? The following essay is an attempt to explore Marmont's role in the defence of Paris and Napoleon's first abdication,

In the early months of 1814 Napoleon fought one of the best campaigns he had ever fought, one of the key officers of this campaign was Marshal Auguste Marmont. He commanded the 6th corps d'Armee. A formation he had lead for over a year and with which he fought throughout the campaigns of 1813. Wounded at Leipzig, Marmont was back in the saddle for the 1814 campaign and fought again at the head of the 6th corps d'Armee. Present at the battles of La Rothiere, Champaubert, Vauchamps and Laon, where he was almost destroyed.

But it is after the battle of Laon that our interest really begins, when Marmont's corps together with Marshal Mortier's Guard corps is left to watch Blucher's Silesian Army whilst Napoleon swept south to deal a swift blow to Schwarzenberg, the Austrian Commander. Marmont and Mortier have about 16,000 men combined, whilst Blucher has an army of 80,000 men, the odds were distinctly in the favour of the Prussian. Marmont's instructions were to delay Blucher's advance on Paris in order that Napoleon would have sufficient time to defeat Schwarzenberg and hopefully win the war.

Well at First

At first all went well, Marmont retired slowly and at Fismes he fought a rearguard action but then at the battle of La Fere-Champenoise he was badly beaten by the superior numbers of the Allies. The position Marmont had chosen was good defensively but the weather spoilt his plans and the Allied cavalry were able to inflict substantial losses on him before he was able to withdraw. After this set back Marmont fell back on Paris, reaching the city on 29th March 1814. There he found the city barely prepared for defence and the Minister of War, General Clarke, and General Hulin the garrison commander, far from committed to a rigorous resistance.

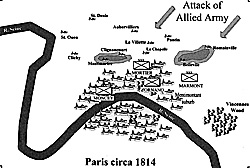

Marmont himself took command of the troops on the right flank, mostly his own Corps d'Armee but supported by ad hoc divisions of the Imperial Guard organised under General Count d'Ornano. Marmont was expected to the plateau of Romainville, the hills of Belleville, Saint Chaumont and the neighbouring villages of Charonne, Menilmontant and Pre Saint Gervais. His colleague Marshal Mortier had been assigned the left flank, which he was to defend with his Imperial Guard divisions and which covered the hills of Cinq Moulins and Montmartre and the villages of Aubervilliers, Saint Denis, Saint Ouen, Clignancourt, La Villette and La Chapelle.

On Mortier's left were the cavalry divisions of Belliard and Dantancourt. Between Marmont and Mortier stood the Imperial Guard formations of General Count d'Ornano ready to intervene on which ever flank they were needed. And behind these troops there was Marshal Moncey and his national guard, half of whom were only armed with pikes.

Battle Joined

The expected battle began early the next day, when General Barclay de Tolly's Russians attacked Marmont's troops on the plateau of Romainville. A sharp combat took place and d'0rnano reinforced Marmont's left at the village of Pantin with one of his divisions, and thus supported Marmont's men held the plateau despite Barclay de Tolly's superiority in numbers. On Mortier' sector his guardsmen were late in getting into position but thereafter deployed in support of the combat occurring at Romainville and Pantin village, whilst the cavalry of Belliard and Dantancourt manoeuvred in the vicinity of Saint Denis and Cligancourt

It was now that another Allied advance was perceived, General Langeron and General Vorontsov's Russians were attacking the village of Aubervilliers, which was held by one of d'Ornano's formations. Mortier's artillery batteries at La Villette opened fire but the Russians still drove the French out of Aubersvilliers and attacked Mortier's main positions. Mortier, heavily outnumbered, turned his formations to face this threat but despite the gallantry of his troops was forced to retire unit by unit and fighting all the way because he was so heavily outnumbered. By night fall he was fighting in the Paris suburbs along with Moncey's national guards.

Marmont on the other flank, having halted Barclay de Tolly's first assault, now found himself faced by a reinforced Barclay de Tolly and with both Mortier and d'Ornano committed elsewhere he was very much alone. Marmont responded to the challenge with great courage, personally leading charge after charge with his tired troops in an effort to stem the tide but again like Mortier, he found himself forced back into the Paris suburbs. It was during this phrase of the battle that Marmont was informed by Joseph, Napoleon's Lieutenant General in Paris, that if he and Mortier could no longer hold their positions, they were authorised to negotiate with the Allied armies facing them and then retire to the Loire.

Nothing had been further from Marmont's mind, he had intended holding on outside the city gates until dark and then fighting in the streets the next day but Joseph's order charged this. It did nut give Marmont the authority to fight for Paris street by street, instead it required him to get the best possible terms if he and Mortier were driven from their positions and then to bolt for the Loire valley. Marmont sent for clarification but his emissary, Colonel Fabvier, could not find Joseph, nor General's Clarke or Hulin. They had all left the city. It was also the moment that General Dejean arrived with a order from Napoleon to keep on fighting.

By now Mortier had joined Marmont and read Joseph's order, he was genuinely disheartened by it but agreed that Marmont's hands were tired. Together they arranged a meeting with the Allied representatives, Count Orlov and Count Nesselrode on the outskirts of La Villette, Mortier's front line. But even as they were talking fighting flared up again and it was only thanks to the "Doyen of the Marshals", Moncey, that the Allies were stopped from entering Paris that night. Marmont and Mortier of course were horrified that fighting should flare up whilst they were negotiating with the Allied representatives and even more infuriated when the Allied representatives began to make demands.

By this time Mortier had had enough and left the negotiations to Marmont, returning to his troops who he ordered out of Paris that night to save them from any Baylen-like Capitulation and he took time to make sure that they took all the stores and ammunition they could with them. Meanwhile, Marmont had arranged an armistice and agreed to withdraw his troops by 9.00 o'clock the following morning. The Allies for their part, readily agreed, for they needed the supplies Paris could offer for their own armies and calculated that the French Marshals would not have enough time to remove all that Paris possessed, plus they wanted to take Paris before Napoleon could arrive and upset their plans.

Hero of the Hour

Marmont, who it has to be said had fought heroically in defence of Paris, arrived at his Paris home that night to find himself the hero of the hour, literally toasted by the high and low dignitaries of that city as their savour and the man who would bring peace! He must have felt on a high as the centre of all this adulation, especially after the set backs of the day and indeed the campaign of 1814 as a whole. Tired and wounded in the fighting for the heights of Romainville, he must have been easy prey for the intrigue of Maurice Talleyrand, despite his well known intellect, he was said to be perhaps the best educated of Napoleon's Marshals. But sadly he was only a soldier and really no match for the political manoeuvres of Talleyrand, the ex-Bishop of Autun and a political animal par excellence, an unprincipled fellow who have given Machiavelli a thing or two to think about.

Thus in the early hours of a new day Marmont found himself exposed to the full fury of Talleyrand's wiles, which to cut a long story short, entailed convincing Marmont that Napoleon and his regime had failed him and left him and him alone to fight the entire Allied army for the possession of Paris. In short it was time to look out for oneself and if Marmont wanted to be in on the winning side he should act now. Talleyrand's arguments had much weight and had much truth behind them and Marmont, one of Napoleon's closest friends, no doubt felt the weight of them and they effected his actions later on.

What Marmont did not know was how close Napoleon really was and the efforts he had made to reach Paris in time. But that morning there were decisions being made and actions taken that would have far reaching consequences.

That night Napoleon had reached Juvisy, exactly ten miles from Paris. There he had met General Belliard and his cavalry, who had fought earlier in the day in the defence of Paris, and learned of Marmont's armistice with the Allies. Despite this unwelcome news Napoleon awaited the returned of General Flahaut, an aide-de-camp, for confirmation of the news. On Flahaut's return and finding that Marmont's, Mortier's and Moncey's troops would soon be retiring in his direction, Napoleon decided to move to Fontainebleau and concentrate his army there, as well as planning his next move. But he would find that his next move would be dictated not by him but his Marshals, for Marmont was not the only one beginning to have second thoughts and starting to think of looking after themselves.

The next morning, Marmont in accordance with his agreement with the Allies, evacuated his troops from Paris and marched them toward Essone, the direction Mortier had already taken the night before, he was then at Mennecy - just beyond Essone. Moncey had orders to follow with his national guardsmen as soon as the Allies had taken over responsibility for security within the city of Paris. Though before Moncey could do so he found himself replaced by General Dessolle, who had been appointed on the authority of a new provisional government that

Talleyrand had hastily set up. The "Doyen" therefore joined Napoleon at Fontainebleau.

Restoration

The next day Napoleon visited both Mortier and Marmont in their camps along the Essone river and was received with enthusiasm by the troops and planned to reinforce them as soon as possible. Dining with Marmont, Napoleon received a first hand account of the defence of Paris and the half - heartedness of Clarke, Hulin and Napoleon's brother Joseph. They must also have discussed the political situation in Paris where the provisional government had deposed Napoleon and called for the restoration of the Bourbons. But Marmont was careful not to mention that he was still in contact with Talleyrand was allowing proclamations and letters to circulate freely amongst his own officers.

Indeed the situation was very vague, for if Napoleon was legally deposed by the French government, then where did this leave Napoleon's officers and what would happen to their titles, property and pensions if they continued to serve Napoleon? Would they be branded as traitors?

This anxiety affected not only Marmont's officers but many others too. Marshal MacDonald for instance, not only obtained a copy of some of the literature in circulation but presented to Napoleon in person and voiced the concerns of many. Indeed, it was undoubtedly considerations such as these that prompted Marshals Ney and Macdonald, supported by Marshals Oudinot, Lefebvre and Moncey, to insist upon Napoleon's abdication in the famous mutiny of the Marshals a few days later.

Meanwhile, Marmont assured his own officers, particularly the Generals Souham, Compans and Bordessoulle, that he believed that, if they adhered to the new government then their positions within society would be secure. After all, the government represented the will of the people of France, whilst Napoleon was only one man and he had been deposed by a legally assembled legislative body the Senate. Of course they did not know that Talleyrand's hand behind it all and he had manipulated the proceedings to get the result he wanted.

Moreover, Talleyrand now used what influence he had gained over Marmont to assure him that he and he alone held the fate of France in his hands. Talleyrand now urged Marmont to take the lead and show the way to others by openly supporting the new government with his own troops then at Essone. By defecting he would save France from possible civil war and would in addition be seen as her saviour, as well as retaining his present titles, indeed he could gain fresh titles if he helped the new government in its hour of need.

By the 3rd April, Marmont was probably convinced by this line of argument and had decided to comply with the wishes of Talleyrand. Indeed he had probably decided upon his next action and discussed how to implement with his chief officers, General's Souham, Compans and Bordessoulle. However on 4th April, Marmont received a severe shock when Marshals Ney and MacDonald, together with General Caulaincourt, one of Napoleon's closest confidants, had arrived at his headquarters with the startling news that Napoleon had abdicated in favour of his sun and thus negated the whole legality of what he had intended to do that very day. He confessed the whole sorry tale to his fellow Marshals, who agreed that he should accompany them to try and undo some of what he had already done. Meanwhile, he the strictest orders to his second in command, General Souham, not to move or implement their planned defection until his return. Marshal MacDonald confirms this in his recollections.

The arrival of the Marshals in Paris caused a great stir, especially amongst members of the new government, which had much to lose if the Allies and in particular, the Russian Tsar Alexander, accepted Napoleon's abdication in favour of his son. Indeed, the Tsar seemed very amicable when the Marshals had their first interview with him and expressed his firm intention of arguing in favour of Napoleon's son to his fellow allies. The Marshals then retired to Ney's Paris house for the night.

The Plan

However, unbeknown to them, that very same day General Souham, left in command of Marmont's corps, received from Napoleon orders to report to him in person at Fontainebleau. Suspecting that Napoleon may have found out about Marmont's defection plan, Souham took fright and with the support of Compans and Bordessoulle put Marmont's plan into action that night, despite the clear orders from Marmont nut to do anything until his return, and the sent the 6th corps off to Versailles where found themselves surrounded and disarmed the following day.

This single act not only robbed Napoleon of 14,000 experienced soldiers but also wrecked his own offer of abdication, for it indicated that the whole of the French army was not behind him and at the same time it strengthened the position of the provisional government.

Marmont was at Ney's house having breakfast when he learnt of Souham's actions and made the famous remark: "I would have given my right arm to prevent this happening." To which, Ney had replied: "Not even your head would be enough." Napoleon's plan for a regency was finished and following Marmont's example other Marshals began to desert Napoleon and swear allegiance to the provisional government (soon to be a Bourbon restoration).

Talleyrand had won. He had used Marmont well and achieved his ultimate aim which was a Bourbon restoration. Marmont too had his moment (though this was to prove very brief) as a hero of the Royalists and the Provisional government, though it had been his generals who had actually done the deed. But he also suffered for it and his reputation still does. Indeed, his ducal title, Duc de Ragusa, give rise to a new word in the French language of the time, ragusade (betrayer). And Napoleon named him as one of two men who had betrayed him in 1814, the other was Marshal Augereau, who had surrendered Lyon without a fight. And of course, history has named Marmont as the arch-betrayer of Napoleon in 1814. As Napoleon himself put it: "That Marmont should do such a thing; a man with whom I have shared my bread."

And yet, if we take Marmont's actions at face value and bear in mind the political manipulations of Talleyrand, not to mention the subsequent speed of the other Marshals in defecting to the provisional government. We see a soldier who had fought long and hard for his country, who saw that he had an opportunity to bring peace to a war weary land and who had the best interests of his country at heart. Placed in a difficult situation and endeavouring to make the best possible decision.

Unfortunately for Marmont, the celebrated "Mutiny of the Marshals" occurred at the same time and totally negated his own efforts and end result was the total vilification of his character and intentions, whilst the real culprits escaped the subsequent attention of history. Marmont has, it can be argued, become something of a scapegoat for the inertia, manoeuvring and treachery of others. It is sad, for Marmont deserves better. He was a fine soldier and administrator but for one act he has acquired a reputation he probably does not deserve but then that's life for you!

Chandler, David G. (ed.) Napoleon 's Marshals (Weidenfeld & Nicolson London, 1987).

|

To most Napoleonic enthusiasts the name Marmont conjures up images of defeat and betrayal, Marmont being heavily defeated at the battles of Salamanca (1812) and Laon (1814), and the man who is often seen as the prime betrayer of Napoleon in 1814.

To most Napoleonic enthusiasts the name Marmont conjures up images of defeat and betrayal, Marmont being heavily defeated at the battles of Salamanca (1812) and Laon (1814), and the man who is often seen as the prime betrayer of Napoleon in 1814.

Marmont himself did everything he could do to put the defences of Paris in a state of defence and in this he was ably supported by Mortier, Moncey, the depots of the Imperial Guard and the National Guard. Occupying the heights to the north of the city, he hoped to delay the allies long enough for Napoleon's Army to appear and save the day.

Marmont himself did everything he could do to put the defences of Paris in a state of defence and in this he was ably supported by Mortier, Moncey, the depots of the Imperial Guard and the National Guard. Occupying the heights to the north of the city, he hoped to delay the allies long enough for Napoleon's Army to appear and save the day.