Any visit by students of the Peninsula War should take in the Irish College (today the Coledgio Fonseca) the site of a large British hospital in 1812 and the site of the converted convent-forts covering the bridge (the forts are no longer there).

The Battlefield

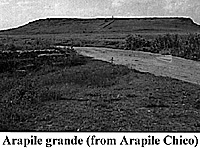

South of the city is the battlefield, taking the Ciudad Rodrigo road. The first things you notice are the Arapile Chico (Lesser) and Arapile Grande (Greater); the two rocky outcrops that mark the entrance from the east to (and also dominate) the battlefield. They make excellent grandstands (as the Arinez knolls do at Vittoria) to climb then sit, plotting the course of the battle. From the top of the Chico, looking over to Nuestra Senora de la Pena, perched on the hillside to the north, you can with little difficulty (well some of us anyway) imagine the two armies creeping along; the Allies behind the crest and partly invisible, and Marmont's marching divisions snaking forward to try to snip off Wellington's retreat back to Portugal. Behind the French, stretching over towards Alba de Tormes, a dark blur of scrub and woodland; beyond the Allies, a large plain of grass and some fields of meagre crops around the village of Los Arapiles.

From up here, this part of the battlefield before you looks flat it isn't. Like Waterloo, you need to go down to ground level and walk around to get a view from a soldiers point of view. Small rises and undulations in the ground alternately hide and highlight important features of the battlefield. The woods over towards the main road are no longer there - in 1812 a view over there would have shown a large plume of dust, which Marmont took to be the retreating Allies; it was the baggage of the army headed out towards Rodrigo. Hidden by the nature of the ground and the dark mass of the woods, the 3rd Division under Pakenham waited for orders, hidden from the French telescopes near the village of Aldea Tejada.

It was a hot day after the thunderstorm the night before. The French had filled all their water bottles at the fords of Huerta. The dust and the heat soon emptied them. They had been manoeuvring around Wellington for weeks - both sides knew the risks of even a drawn battle. The French could march faster than the Allies - this morning a chance had been seen for this speed to be used to isolate part of the Allied army before they could all reach safety; this could cause disorder which could be exploited. Marmont was confident - he had already retaken Salamanca. It communicated to his leading divisions - a battle won by manoeuvre and strategy was preferable to one fought against the aimed fire of brown and green-jacketed skirmishers preceding the terrible redcoat reverse-slope lines of musketry.

You can trace through a telescope the approach of the 3rd Division - they emerge from the woods and before the French can attempt a defence, have struck - worse than that, they are followed by Heavy Cavalry. In a set-piece charge, the troopers crush two brigades, and go on. "40,000 men were not defeated in 40 minutes" as the popular saying goes, but they were hurt and hurt very badly. Fate (a fickle goddess at the best of times) also played a hand - the gunners on the Arapile Chico wounded Marmont with a splinter from a case-shot.

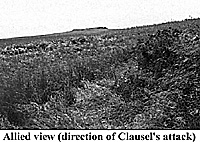

These fell back in the face of this fire, exposing the 4th Division to the French fire - more French infantry joined in, and Lowry Cole, the general commanding the 4th Division, fell wounded. Clausel threw both his division and those of Bonnet (the dead French second in command) into a column attack at this division, now weakened and shaken. From behind the Arapile Grande, a large mass of troops in column - as yet invisible to the men of the 4th Division because of the rising ground, but not to Wellington on the hillside behind - began to move off towards Los Arapiles, and onto the flank of the rest of the Allied army descending from behind the cover of the ridge. Rising up a slope halfway between the hill and the village; drums pounding, Eagles blazing, men shouting, the steady thud of booted feet in unison - the mass of French troops marched slowly forward covered by a cloud of skirmishers in an oblique line across the plain, pushing back before them both Pack's Portuguese and the leaderless and shaken 4th Division. Beresford, now unemployed by Wellington after Albuera, 'borrowed' a brigade from the 5th Division over to the French front over 300 yards away and tried to stop them.

In a furious fifteen-minute firefight, he fell wounded too, his borrowed troops shredded and shaken. Clausel advanced at the pas de charge a la bayonet once more after this short interlude - had he broken the Allied line and saved the day for France ? What was over the smoke-skeined hill to his front ? Victory, or...?

6th Division

The Allied 6th Division had been moved personally by Wellington to meet this threat - cresting the hill 250 yards to the French front and flank, partly invisible in the smoke, they advanced stumbling and blinking to within 100 yards, then their fresh volleys added to the grey smog of the previous firefight and slowly tore into the columns tramping obliquely past their front. With them, on their left, came batteries of artillery, who unlimbered on the crest and fired at close-range into the depth of the French flank.

For a time in this natural ampitheatre, volleys crashed out from both sides, studded with blasts from the cannons on the hillside. The Allies were already in line - the French, some with armes a repos couldn't deploy as they were hemmed in and under heavy fire. Muskets and men were already hot and tired, the gunflints worn out after defeating Beresford's troops - out of the growing cloud of powder smoke blowing across the battlefield and obscuring the view, confusing and disorientating, soldiers stumbled away from the fighting, the French going in ever-increasing numbers towards the Arapile Grande, and the way back to the crossing at Alba de Tormes.

Maximilien Foy - a very able French general who had more than his share of campaign adventures through being in just the right place at the right time saw this and formed his division across this line of retreat. Foy formed in line - for a long time his leading brigade fired steady and regular volleys and held off the attacking Allies, allowing his countrymen to get away safely. Their powerfully delivered and clean-loaded volleys from a three-deep line shredding the pursuit should have given the French a lesson in how to conduct battles safely in Spain in the future. Their commander, Ferrey, was cut in two by a cannon ball fired from flank and rear by Allied reserves brought up by Wellington and they too, fell back, the lesson in volleyfire unnoted and unlearned.

Local Lore

Many years ago I met a Spanish gentlemen who had studied this battle many years before that. He told me all about it; the epic battle in the struggle by his countrymen to liberate their land from the invader (he was a little vague here as to who he classed as the invader sometimes - Moor, French, British, Portuguese or simply a polyglot all of them). He told me how after the battle the villagers of Los Arapiles had returned from hiding and seen hundreds of dead soldiers lying in the wind-blown and downtrodden grass.

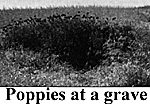

Stripped of their regimentals, belts and muskets, the problem of where to bury them remained. A deep track which crossed the plain was used; the soldiers laid abreast in it, and the steep banks of the ruts caved in on top of them (a strange echo of this incident came back to me; I was sitting in La Haye Sainte at dusk looking out over the field of Waterloo in 1985, where this method was also used to bury dead after the battle there). A natural hollow near the village was scraped larger, and heaps of dead British soldiers filled it up. The earth scraped out was now thrown back in on top of them. A crude marker was placed there by one of the religious Spanish peasants.

On Pakenham's hill; where indifferent villagers from Miranda village made a poor job of burying the French dead; in months to come, animals; both natural and human; later excavated the bodies and left whitened skulls clustered on the hilltop. I found another unpleasant echo of this sort of desecration on the Crimean battlefields of 1854/5 & 1942/4 when I was there in 1994 - exhumed soldiers, looted of badges and gold teeth, their remains scattered, which we had to collect up and re-inter.

I was to remember this Time and Place in the days to come when I stood looking up before those looming, dark, dismal and forbidding grey walls in remembrance of a dreadful atmosphere in a most disheartening place I had ever dreamed of visiting on my Pilgrimage to the Peninsula.

Another Personal View:

So much has already been written about this place already. The old city is visited by thousands of tourists every year, who view its beauty from the Roman Bridge over the Tormes (I found the skyline strangely familiar, remembering it from the books I'd read); visit the Old and the New Cathedrals; walk around the piazzas of the Plaza Mayor; or tour the ancient colleges and university that made Salamanca in 1254 the 'leading light of the world' (according to the Pope of the time).

So much has already been written about this place already. The old city is visited by thousands of tourists every year, who view its beauty from the Roman Bridge over the Tormes (I found the skyline strangely familiar, remembering it from the books I'd read); visit the Old and the New Cathedrals; walk around the piazzas of the Plaza Mayor; or tour the ancient colleges and university that made Salamanca in 1254 the 'leading light of the world' (according to the Pope of the time).

I found it quite like Oxford or Cambridge in culture, appearance and entertainment, just older and brighter, golden in the sunlight. I chatted with students from Madrid, Paris and Lisbon.

I found it quite like Oxford or Cambridge in culture, appearance and entertainment, just older and brighter, golden in the sunlight. I chatted with students from Madrid, Paris and Lisbon.

Allow two days - and warm nights - to cover everything. There is much to see (if you are of a macabre disposition, visit the catacomb tombs - and don't omit to buy your 'skull and frog' souvenir - the ideal holiday gift!).

Allow two days - and warm nights - to cover everything. There is much to see (if you are of a macabre disposition, visit the catacomb tombs - and don't omit to buy your 'skull and frog' souvenir - the ideal holiday gift!).

Look over to the Arapile Grande (ignoring the disused railway line at the foot of the Chico) and see Marmont and his staff with levelled telescopes - immediately behind you gunners of Royal Horse Artillery sweat and struggle manhandling two guns up to the crest.

Look over to the Arapile Grande (ignoring the disused railway line at the foot of the Chico) and see Marmont and his staff with levelled telescopes - immediately behind you gunners of Royal Horse Artillery sweat and struggle manhandling two guns up to the crest.

Over your left shoulder five hundred yards away is an empty farmyard, just vacated by Lord Wellington, disappearing south-west, galloping away on his horse in a cloud of dust; leaving behind Don Miguel de Alava looking down in disgust at a half-eaten chicken leg on the ground.

Over your left shoulder five hundred yards away is an empty farmyard, just vacated by Lord Wellington, disappearing south-west, galloping away on his horse in a cloud of dust; leaving behind Don Miguel de Alava looking down in disgust at a half-eaten chicken leg on the ground.

The French second in command was already dead. In these instances, the entire thing goes to pieces or a Man of the Moment appears - the man for this moment was Clausel, who not only took charge and steadied the line but created a counter-strike. The British cavalry were disordered and blown, their chiefs dead or wounded. The French left wing/vanguard had gone - but Pack's Portuguese attacking the Arapile Grande had been repulsed bloodily too and chased by a large body of voltigeurs, who shot them up badly and also fired into their two supporting battalions.

The French second in command was already dead. In these instances, the entire thing goes to pieces or a Man of the Moment appears - the man for this moment was Clausel, who not only took charge and steadied the line but created a counter-strike. The British cavalry were disordered and blown, their chiefs dead or wounded. The French left wing/vanguard had gone - but Pack's Portuguese attacking the Arapile Grande had been repulsed bloodily too and chased by a large body of voltigeurs, who shot them up badly and also fired into their two supporting battalions.

A half-hearted pursuit followed. The only bridge over the river Tormes at Alba was held by the Spanish - that was as far as the French would get. By now it was dusk, and the darkness of the woods swallowed what was left of the retreating soldiers. Things didn't quire work out that way - the French escaped to fight another day. The Allied soldiers didn't care - as the moon rose over the Arapiles they fell down exhausted and went to sleep, ignoring the moans and cries that came and went, falling and rising with the cold cutting wind that now blew the remaining smudges of smoke hauntingly over groups of unmoving huddled bodies on the grassy plains . . .

A half-hearted pursuit followed. The only bridge over the river Tormes at Alba was held by the Spanish - that was as far as the French would get. By now it was dusk, and the darkness of the woods swallowed what was left of the retreating soldiers. Things didn't quire work out that way - the French escaped to fight another day. The Allied soldiers didn't care - as the moon rose over the Arapiles they fell down exhausted and went to sleep, ignoring the moans and cries that came and went, falling and rising with the cold cutting wind that now blew the remaining smudges of smoke hauntingly over groups of unmoving huddled bodies on the grassy plains . . .

I never expected to find the grave marker at Salamanca. Nobody had ever written of it before. Maybe it was the similarity in appearance I found between Salamanca and my visits to Waterloo, and the memories it evoked; kneeling down, the handful of earth lifted in my fist fell into dust between my fingers in the heat. Perhaps it was the small cluster of poppies, the only ones there or just the first ones to appear. Maybe it was just luck - and maybe it was Fate. Salamanca was a soldiers' fight too, and both French and Allied soldiers fought stubbornly and bravely. Whatever it was - I left something behind there on that field amongst those scarlet flowers and long grass stalks, bright sunshine, blue skies and whispers of wind... and what I left behind couldn't be in better Company.

I never expected to find the grave marker at Salamanca. Nobody had ever written of it before. Maybe it was the similarity in appearance I found between Salamanca and my visits to Waterloo, and the memories it evoked; kneeling down, the handful of earth lifted in my fist fell into dust between my fingers in the heat. Perhaps it was the small cluster of poppies, the only ones there or just the first ones to appear. Maybe it was just luck - and maybe it was Fate. Salamanca was a soldiers' fight too, and both French and Allied soldiers fought stubbornly and bravely. Whatever it was - I left something behind there on that field amongst those scarlet flowers and long grass stalks, bright sunshine, blue skies and whispers of wind... and what I left behind couldn't be in better Company.

Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #35

Back to First Empire List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 by First Empire.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com