I read what both Rod MacArthur and Simon Vinogradoff have had to say in their respective articles in FE 19 and 20 with great interest and I think both have many valid points.

I agree with Simon’s view to the effect that the measurements quoted in various regulations could not be reproduced exactly, clearly a human being cannot replicate the same pace to the last fraction of an inch every time he takes a step, indeed, the British regulations, for example, are not specific,

“......each man will occupy a space of about 22 inches”.

[1]

Clearly 22 inches is not ‘inscribed in tablets of stone’. Be that as it may, I cannot agree that distances were simply nominal. They were adhered to as near as it was humanly possibly to do. Drill is a science in which the relative arrangement of component parts, the properties and relationships of lines, space and objects are fundamental. The distances specified in regulations were vital both for the individual and the sub-units, neither of which could perform either the manual of arms, at one end of the scale, or the various evolutions and conversions at the other, without sufficient space in which to do so. Without foot drill at the level of the individual and the conversions and manoeuvres it allowed, the simultaneous movements of sub-units at unit level and cooperation between Formations, that is to say Brigades, Divisions and Corps, were simply not possible. The dimensions, intervals and instructions contained within the various drill regulations were absolutely crucial.

I think any assumption that they had no practical application on the battlefield is a tremendously dangerous route to take. The fact of the matter is that although they do include some ceremonial, such as compliments, by far the larger part of them was intended specifically for the battlefield. I would agree with any proposition to the effect that it is very unlikely that Napoleonic battlefields were full of units marching about and firing at each other in perfectly dressed lines and columns, but the evolutions and conversions contained in the various regulations were the only means by which the tactics of the day could be applied. Tactics, it has been said, albeit tongue in cheek but with a degree of truth, are “the opinion of the senior officer present”. The means by which they are applied, nevertheless, are found in the regulations and nowhere else.

Turning now to the specific question of file frontage in the French service, and Simon is quite correct to say that the Règlement 1791 does not specify one, except by implication. Nevertheless, I think I can shed some light on how the 26 inch French file frontage was arrived at. It is based upon three things, the first being the known dimensions of rank distance and so on, the second the premise that a man occupies approximately 9 inches front to rear, the third that the length of a sub-unit formed in column of files must equal its width when deployed in ranks. Let us see if it is possible to substantiate something approaching a 26 inch file frontage. The starting point is with known dimensions. According to the Règlement Provisoire pour le Service des Troupes en Campagne 11eme Octobre 1809”, my copy of which is a German version,

“The pack of the French soldiers is 18 Paris inches wide, 12 inches high and 4 inches thick”. [2]

The first thing to say here is that Simon’s 18 Imperial Inch file frontage is too narrow, if only for the reason that the French pack was wider than this, even Trotter’s notorious contraption was 12 inches by 17 inches, although when the 1792 Regulations were written the envelope knapsack at 17 inches by 19 inches was in use. This discussion, however, concerns the French 1791 Règlement. 18 Paris inches are 19.19 Imperial inches and for the purposes of this exercise I will call it 19 inches. Take 19 inches from the disputed 26 inch frontage and one has 7 inches left, or 3.5 inches for each arm, musket, sabre, bayonet, other equipment and clothing. This does not seem unreasonable to me and would enable elbow contact to be maintained, bearing in mind that it was only touch that was required.

“The man leading this flank............. maintains light elbow touch with the next man, without pushing.

The people in the rank touch the next man with the elbow on the side against the pivot and resist pressure from that side”. [3]

This theme is common throughout all regulations as evidenced in this Prussian wheeling manoeuvre, and the British Manual and Platoon Exercises which states,

“The files lightly touch when firelocks are shouldered and carried, but without crowding.” [4]

There is, however, more evidence to support the 26 inch estimates. Listen carefully, I will say zis only wance.

The Réglement 1791 states that a unit making a flank march in column of files should,

“...........never take more space from front to rear than its width would be when in line” [6]

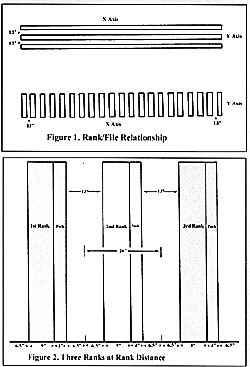

An illustration of the relationship is at Figure 2.

What the regulation is saying is that the X and Y axes of a sub-unit must remain the same whether it be in deployed in ranks or formed in a column of files. If this is the case, then the X and Y axis of the space occupied by the soldier has to remain the same whether he be facing to the front in rank, or to a flank in column of files. If it didn’t, when executing a left or right turn (pivot), the column of files would either expand or contract, thus disobeying the column to line ratio rule. The reason why file width is generally reckoned to approximate to rank distance is evident. Clearly, rank distance was also important in the context of column to line ratio and if not maintained, disorder would result after a turn, further compounded when it converted back into line.

Rod’s comment in the context of flank marches ‘en tiroir’ is entirely appropriate, indeed, it was absolutely essential that the axes remain the same in order to conduct them. If they did not, the sub-units would not be able to deploy onto the new alignment accurately.

Another known dimension pertinent to the discussion is rank-distance, specified as follows.

“The distance of a rank to another will be one Paris foot, measured from the chest of the men in the second and third ranks to the backs of the men preceding them in their respective files, or his pack when loaded”. [7]

This is repeated in the Westphalian regulations. [8]

The Paris Foot, “un Pied”, measured 12.79 Imperial inches and usually rendered as 13 Imperial inches.

To summarise so far,

First, the Règlement 1791 states, unambiguously, that the depth of a formed column of files may not exceed the width of the same sub-unit when it is deployed in line.

Second, the logic of this is that in order to obey the instruction above, the space the soldier occupies when facing to a flank in file may not exceed that which he occupies when facing to the front in rank.

Third, although the Règlement 1791 does not specify a file frontage, it does specify a rank distance.

Fourthly, we know that the rank distance was “un pied” or 13 Imperial inches.

Finally, in the certain knowledge of rank distance and pack depth, we can say that the depth of a three rank file, where the soldier is S, is as follows. S + 4” (pack) + 13” (rank distance) + S + 4” + 13” + S + 4”.

However, because each soldier shared the space to his front and rear, he actually ‘owned’ only half the rank distance, 6.5 inches, in each direction. Furthermore, no substantive discussion has yet been made of the space occupied by the soldier himself and here, of course, variations are inevitable. How much space should we allocate? We have seen that the French pack was 4 Paris inches deep, which we ought to take into account, although the difference between that and 4 Imperial inches is so small as to be insignificant in this case (.32 Imperial inches) but what the wearing of packs means, if the regulation distance of 13 inches from chest to pack is to be maintained, is that the soldier is approximately 4 inches further away from the man to his front. This appears to have one of three consequences.

First, in order to maintain rank distance, the soldier must lengthen his pace if he is to step in the space vacated by the foot of the soldier to his front or,

Second, if he maintains the pace and rank distance he can no longer step in the space vacated by the foot of the man to his front or,

Third, if he maintains the pace but closes the rank-distance by 4 inches he disobeys the regulations, but is able to step in the space vacated by the foot of the man to his front.

I suspect, but can’t prove it, that the second option was used when “loaded” for reasons which will become, I hope, clear.

So, If one accepts that the X and Y axis are to remain the same length, as required by the Règlement 1791, one must also accept that the rank distance of 13 inches has to maintained regardless of whether the sub-unit be in deployed in ranks or formed in a column of files. As already suggested, this means that the same space must be also occupied by the soldier regardless of the direction in which he is facing or, in other words, his frontage should also equal his depth. If we accept an estimated 22 inch frontage, S must be the difference between 22inches and 17 inches (rank distance of 13 inches plus pack depth of 4 inches), which is 5 inches. I don’t believe you can stand a man in with his equipment and weapon, and expect him to use it, in a space only five inches deep. My 9 year old son’s size three and a half shoes, for example, are 10 inches long!

Alright, try a 26 inch frontage. In order to substantiate this, we must find a 26 inch depth also, because, at risk of being repetitive, if the X and Y axis of the sub-unit cannot alter, neither can the X and Y axis of the space occupied by the soldier. If the soldier was to occupy a different space when in column of files, then the dimensions of the sub-unit in column of files would be different from its frontage when re-deployed in ranks. This is not permitted.

To persevere. Take the established rank distance of 13 inches and the established depth of pack of 4 inches, a total of 17 inches, away from the postulated 26 inches and one arrives at 9 inches left in which the soldier can stand, which I think is more reasonable but still not overly generous. This, nevertheless, has been accepted by a number of authorities as a reasonable estimate. What it now gives us is a depth for three ranks as follows, 9 “(soldier) + 4” (pack) + 13” (rank distance) + 9” + 4” + 13” + 9” + 4”, a total of 65 inches, or roughly(ish) Simon’s 2 metres. An illustration is a Figure 4.

Yes, I know, the 9 inch figure is too convenient for words and one could argue that it is too small, too large, that soldiers are not all ‘issued’ in the same size and shapes, and you would be right. There are also the ramifications of not wearing packs that I have not even considered. Readers who have got this far can do the calculations for themselves. I have had enough!!

I merely offer this as an explanation for the 26 inch file frontage in French service. The logic, however, of the soldier occupying the same depth as he would width is implied in the statement in the Règlement 1791. Once the depth has been established, the implication is that so has the width. The extrapolated figure of 26 inches has, therefore, been used by generations of expert commentators from, I would guess, Cdt Colin onwards, and whether one accepts the estimated measurement of 9 inches for the soldier himself or not, total space allocated him must be the same in depth as it is width in order to conform with the Règlement.

A related word on paces, of which there were four in the French service, shown below in their Imperial approximations.

Stepping long, or short, however, was specified in all regulations when necessary, and, indeed, was essential when conducting manoeuvres such as wheeling. This, however, does not matter so long as a return to the standard Pas de deux Pieds was made. The soldier might pivot left or right and about-turn, as many times as he likes, the 13 inch rank distance would be preserved.

What, I hear the exhausted reader ask, is the point of all this? Simply this, rank distance was not an arbitrary figure and was very probably geared to the regulation pace, in this case a stride of 26 inches, the ‘Pas de deux pieds’, and was related to the file frontage. Finally, that X and Y axis had to be maintained regardless of the direction in which the soldiers were facing. To borrow Wellington’s sentiment at this point, I would have written a shorter article but didn’t have the time!

Turning now to cadences, there were four in the French service.

As to the question of cadence, although it is quite true that the Pas Ordinaire was used under most circumstances, I can’t agree with either Rod’s or Simon’s conclusion that faster cadences were used only in emergency, if by that they mean infrequently. The French Règlement 1791 is quite unambiguous on this point, the Pas de Charge was used for all conversions. The point that Rod makes, however, to the effect that the officers and NCO cadre would not allow deviation from what was taught seems to me to be entirely relevant. As for Philip Haythornthwaite’s apparent assertion that use by the Austrian’s of their 120 to the minute cadence doublirschritte was a rarity, this is not reflected in the regulations. The Exercier-Reglement 1807 is equally as unambiguous as its French peer, the 120 to the minute cadence was used for all conversions and otherwise whenever speed was necessary. [9]

What it does say is this,

“the last sub-unit, through use of the schrägen doublirschritte often arrives on the formed line greatly tired” [10]

This is in the context of the oblique doublirschritte, and says nothing about disorder, only fatigue. This is not necessarily the same thing, although I do concede that it could be. Although slower cadences were used generally, the faster cadences were prescribed in numerous circumstances in all regulations,

“It is an important rule, that the Prussian Infantry in advancing against the enemy, should continue the common easy step, whilst exposed to round shot, but as soon as they come within reach of grape, the word will be given “Quick March” on which the pace is augmented to 108 steps in the minute............” [11]

The same instructions also state,

“The cadence of the ordinary march is therefore fixed at 75 in the minute, the length of pace 2 Feet, 4 Inches Rhine measure (approximately 29 inches Imperial).

The march called the deploying march, shall henceforth be called the Quick March as it will used not only in deploying, but in many other situations. The cadence of it will remain at 108 in the minute, and in advancing to the front will be of the common length of 2 Feet 4 Inches.

The above cadence and length of step must be practised by all Officers, non-commissioned Officers and privates, but more especially by the Sergeants and Colour Bearers who regulate the step of the battalion in advancing and retreating.

The Troops must likewise be practised to take up during the march to the front whatever step, the circumstances of the manoeuvre render most expedient.

The Quick March of 108 steps in a minute may be used on many occasions viz:

In the wheeling of divisions.

In the formation on adjutants.

In the separation of battalions from column by inclining.

In deploying.

In the attack with bayonets

In case a battalion shall find itself so far behind the line, either in advancing or retreating as not to be able to regain its place by the lengthened step in the usual cadence, which however will continue to be used as formerly when practicable.

In inclinings of the line by sections, if it is wished to gain the enemy’s flank quickly.

In the retreat en Echequier, when a battalion, attacked by cavalry, has remained far behind, and wishes to regain its place, after having repulsed the enemy, or where it is desirable to occupy expeditiously a height or other advantageous ground.

In changes of front of a line, when the flank battalions will have to describe a proportion of a large circle. In short in all cases where ground is to be gained and the Commanding Officer orders the Quick Step to be made use of.” [12]

It is obvious that there were few restrictions on the use of faster cadence in the Prussian service. Consider also the Pas de Course of 200 to 250 paces to the minute, specified in earlier French regulations and which was still, apparently, made frequent use of, [13] and the 200 paces to the minute Geschwindentritt used by the King’s German Legion [14]

As far as the main thrust of Simon’s article in concerned, whilst he is quite correct that close order ranks were essential for the delivery of musketry, it is worth pointing out that prior to the use of cadence units had to halt in order to close ranks before firing. The ability to march in close order, however, was the product of cadence which was adopted in order to facilitate manoeuvre, not musketry, and evolved in the mid-18th Century when armies were somewhat smaller, generally better trained, and certainly used different tactics from those during the Napoleonic period. Therefore, the benefits of close order marching, as far as musketry was concerned, were a matter of accident, rather than design.

I also tend to question the alleged efficacy of Napoleonic musketry in general, which I think may well be over stated, and the fire of the third rank in particular. I concede this needs a separate study although it is worth mentioning that in both the Austrian and Prussian service the skirmish element was found from the third rank, and what Napoleon himself thought of the third rank is well known. It is also apparent that Marmont and St Cyr held similar views (“we agree with you Sire” perhaps). [15]

The Napoleonic period was marked by the raising of mass conscript armies, the ranks of which were filled by individuals who were

“more densely stupid than it easy for any one in the twentieth century to conceive” [16]

Even if one considers Maude’s 20th Century observation somewhat extreme, it cannot be denied that these were very unsophisticated people by today’s standards but, though conscripts they might have been, I doubt that their intellect was any different from that of their fathers’, some of whom would have marched in the ranks of 18th Century armies. The drill regulations used during the period were all 18th Century in origin, or evolved from them and were intended to be executed by precisely such people as described by Maude. I am absolutely certain that what Napoleonic soldiers were taught, be it ever so limited, and I’m not convinced that it was, was taken from the pages of the regulations.

The drill, the evolutions and conversions of the regulations in use during the early 19th Century were, if not tactics in themselves, directly connected to tactical behaviour on the battlefield in so far as they determined what could be done. I would resist any suggestion that the regulations reflected theory rather than actual practice, and that they had little or no bearing on what actually took place. If this is correct, I have never seen any sensible explanation of what did.

To suppose that the regulations were largely ceremonial, theoretical, nominal, or that something else was performed on the battlefield, is simply not credible. Although I can accept that re-enactment might have something to offer at the level of the individual, or perhaps smallest sub-unit, I think it a very dubious proposition indeed to extrapolate the findings of what, by any standards, are a comparatively small number of people and apply them to evolutions in a multi-unit setting, such as battalion, let alone regiment and above. Bear in mind that the orders given to the soldier and sub-unit, contained in separate documents such as the Austrian Abrichtungs Reglement and the British Manual and Platoon Exercise, or incorporated in the main regulations, such as the sections in the French Règlement 1791, Ecole du Soldat and Ecole de Peleton, and corresponding parts to the Prussian regulations, are not necessarily the same as those given to the battalion or regiment. I simply cannot take seriously, the proposition that re-enactment is able to “test the practical application” of any Napoleonic regulations above the level of the individual or smallest sub-unit, any more than playing wargames gives an insight into what it was like to command a Napoleonic Army Corps.

What are really required are contemporary accounts of tactical practice, together with a thorough study and understanding of the regulations which often assume a degree of knowledge we do not always have today. This can make interpretation of what is meant somewhat fraught. Although I concede a potential role for re-enactment here, I would place a significant caveat on its use as a model. Drill at the level of the soldier is mindless and simplistic in that little intellect is required of him. To paraphrase Clausewitz, however, war is the province of uncertainty where even the simplest things become difficult. What price re-enactment in that context?

Whilst I tend towards the view that in our insatiable pursuit of certainty there is always a danger of loosing sight of the need to interpret parts of the mass of information available to us, I suspect that neither re-enactment nor wargaming replicate the kind of sensory contact with the subject necessary to provide the knowledge we seek. Such creative thinking is too often based on hunches, guesses, and opinions of obscure origin to be really useful. It would be a mistake to take what are no more than agreeable hobbies too seriously.

References:

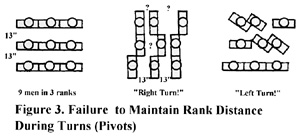

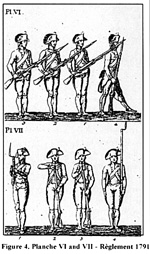

[1] The Manual and Platoon Exercises. London 1809. p47. This is not quite the scenario described by Simon who I feel emphasise the closeness of the ranks a little bit too much, indeed, the illustrations in the Règlement 1791 accompanying this article show that there was no contact between the soldier’s elbows and sides, and that his arm was actually slightly bent, sufficient for there to be daylight between waist and joint. Indeed, the manual of arms clearly requires sufficient space for it to be performed. An illustration is at Figure 1. [5]

This is not quite the scenario described by Simon who I feel emphasise the closeness of the ranks a little bit too much, indeed, the illustrations in the Règlement 1791 accompanying this article show that there was no contact between the soldier’s elbows and sides, and that his arm was actually slightly bent, sufficient for there to be daylight between waist and joint. Indeed, the manual of arms clearly requires sufficient space for it to be performed. An illustration is at Figure 1. [5]

An, admittedly graphic, illustration of the effect when this is not obeyed is at Figure 3.

An, admittedly graphic, illustration of the effect when this is not obeyed is at Figure 3.

It will be noted that the figure for the soldier plus pack equals 13 inches, which, when added to the 13 inches rank distance, chest to pack, comes to 26 inches. Can it be coincidence that this is the same as the standard pace? Well, probably.

It will be noted that the figure for the soldier plus pack equals 13 inches, which, when added to the 13 inches rank distance, chest to pack, comes to 26 inches. Can it be coincidence that this is the same as the standard pace? Well, probably.

Petit pas (half pace) - 13 inches (un pied).

Pas de deux Pieds - 26 inches.

Pas elonce - 33 inches.

Grand pas - 40 inches.

Pas Ordinaire - 76 to the minute.

Pas de Route - 85-90 to the minute.

Pas Accéléré - 100 to the minute.

Pas de Charge - 120 to the minute.

Permanently.

[2] Auszug aus dem provisorischen Reglement für den Dienst der Truppen im Felde 1809 11ten October 1809. Darmstadt 1811. p172.

[3] Exerzir-Reglement für Infanteri der Königlich Preußischen

Armee. Berlin, 1812. p39.

[4] Manual and Platoon Exercises. op.cit. p47.

[5] Règlement Concernant l’Exercice et les Manouevres de

l’Infanterie de Premier Août 1791. Paris, n.d. Pl. VI and VII.

[6] Ibid. Ecole de Bataillon. para 146.

[7] Ibid. Formation d’un Régiment en Bataille. p3.

[8] Reglement für die Königlich Westfalischen Regimenter. op.cit.

Formation eines Regiments in Schlachtordung, p5.

[9] Exercier-Reglement für die k.k. Infanterie 1807. Wien, 1807.

pp19-20.

[10] Ibid. p92.

[11] Instruction for the Infantry. Berlin, 1798. Manuscript

translation. n.d. p8.

[12] Ibid. p11-12.

[13] Nafziger, George. Tactical Maneuvres. Empires, Eagles and

Lions, No 92. p8 (quoting Escalle, P. Des marches dans

les armees de Napoleon. Les Règlements. Paris, 1912.)

[14] Exerzir-Reglement für die leichte Infanterie der

Königlich-Großbrittanischen teutschen Legion. 1813. p8.

[15] A Review of the History of Infantry. Lloyd, E.M.

London, 1908. p233.

[16] Maude, F.N. Colonel. The Jena Campaign 1806.

London, 1909. p6

Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #23

Back to First Empire List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 by First Empire.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com