Garry Wills asked a number of

questions in FE19 which I intended to attempt in a single response. What

evolved grew 'like Topsy' into three quite separate answers of 'article

length', one of which parallelled a review of the section on Austria in my

article in FE 17, which contains some errors (4 zuge in a company, not 2,

for example).

To forestall those tempted to write in, I have a detailed examination

of Austrian column to line evolutions, including the so called 'mass', as

described in the 1807 Exercier Reglement and 1806 Abrichtungs

Reglement (Training Regulations) in preparation, which should put things

to rights. Similarly, the answer to Garry's question about wheeling and

moving pivots evolved into an article in its own right and that too is

nearing completion. Suffice to say at this point that George Jeffrey's

analysis is, somewhat, misleading in this context.

[1]

It seems appropriate to attempt an answer Garry's last question

first because to do it justice really requires an explanation of how the

tactical and operational art of the early 19th Century evolved from that

of the previous century. Although the prolific use of columns in the

tactical environment, that is to say on the physical battlefield, is but one

manifestation, it is a beguiling and shallow interpretation of Napoleonic

tactical doctrine and, as we shall see, columns also appeared in the tactical

environment of the linear battlefield too. The answer to this question is

nearly as complex as 'The Meaning of Life' and entire books have been

written on the subject.

Anything I say here, therefore, is bound to be somewhat

generalised and superficial. Indeed, nothing I have to say is original

thought and I acknowledge my debt to the works listed in the bibliography

to this article.

It is, nevertheless, a very pertinent question because I don't think

it is fully appreciated that it is in the mid to late 18th Century that one

finds the beginnings of what became Napoleonic tactical and, indeed,

operational art, a comprehensive and readable exposition of which can be

found in Chandler [2] So, despite a

degree of trepidation, I'll certainly offer to fire a volley or two with the

intention of broadening and continuing the most interesting tactical

'forum' currently running in the magazine.

The first thing that needs to be said is that at the tactical level,

Napoleonic warfare had very little, if anything, to do with Napoleon.

Indeed, it has been pointed out by many by many historians, from Colin

onwards, that his record is marked by a dearth of originality in this

context and it is also true, as we shall see later on, that he inherited the

tool which had been fashioned by others before him.

[3]

Napoleon's leadership skills and his ability at the highest levels of

command are so blindingly obvious that no further comment is necessary,

besides, those are not what this article is about.

If one consults a dictionary, one will find that tactics are defined as

"the art and science of the detailed direction and control of movement or

manoeuvre to achieve an aim or task" [4] or "the art5 of disposing military or naval or air forces in actual

contact with enemy" [5] Other

dictionaries offer

similar explanations and none are really adequate, although they do offer

some clues.

Tactics are the art of war at battalion level and below, that is to

say the disposition and control of forces at unit level of command on the

battlefield. Grand-tactics are the art of war at Formation level of

command, that is to say Brigade, through Division, Corps and above. The

term grand-tactics is not much used nowadays and I will use the modem

term 'operations' to denote this activity, because it saves two letters and a

hyphen and, in my view, is a more accurate description.

The object of both is to bring one's own forces into contact with

the enemy under the most favourable circumstances possible. A

comprehensive explanation of all these terms can be found in much

greater detail Chandler's Atlas of Military Strategy. [6]

It is not very useful to examine the tactical and operational

methods of any era in isolation because it is always from preceding decades

that current doctrine evolves and in the case of the early 19th Century it

is necessary, initially, to return to the first decades of the 18th Century.

At that time, although soldiers already marched to a uniform length of

pace, the principle of cadence marching had not yet been adopted and,

thus, it was not possible for bodies of men to march to a specified number

of paces in the minute.

The physical effects of this were essentially threefold. In the first

place in meant that ranks, and files, had to march in open order at

approximately four, sometimes as much as six, paces distant. In the second

it meant that the unit command element spent a large proportion of its

time making sure that dressing was maintained, including frequent halts to

adjust it as it inevitably deteriorated, because, in the third place, bereft of

cadence it was impossible to march in step [7]

It also meant that the because the command element spent so

much of its time making sure that units did not fall into disorder, it had

little opportunity to develop or exhibit much tactical leadership, not that

much was actually required of it, thus the tactical doctrine that evolved

specifically de-emphasised this function.

The Comte de Guibert has been credited by some modem com-

mentators with the invention of the formations and conversions found in

the French 1791 regulations. [8]

Comments are often made to the effect that

Guibert's "system" allowed more rapid deployment and that under it

perpendicular deployment, that is to say a line fonned from a column

facing the direction in which the column was moving, was now possible,

as if it was some kind of innovation. That Guibert introduced closed

columns, and that he made French methods of deployment superior to the

Prussian by allowing the march of files to a flank, as if that too was

something new. [9] Unfortunately,

none of this is correct.

The first ghost which needs laying is the idea that the formations

available to the French Napoleonic foot soldier were either unique to him

or to the period. They were not.

The French 1791 regulations were a virtual repetition of those of

1776 and although Guibert may have been influential in the adoption of

the linear and columnar battalion evolutions contained therein, they were

not his. [10]

Far from being new and revolutionary, all had been in the

Prussian repertoire since the 1750s, even the column formed on the centre

division, as in the French colonne d'attaque, was a Prussian 18th

Century experimental innovation. [11]

If this is true, what exactly was Guibert's contribution? It was, in

fact, absolutely crucial and simply this. He took the formations devised by

the Prussians to meet the problems apparent in linear tactical doctrine and

applied them to a different operational doctrine in a way that had not

been envisaged for them. It is somewhat analagous to the use of armour in

1940. Both the Allies and the Germans had tanks but used them quite

differently. This needs some considerable amplification.

18th Century Deployment

Throughout most of the 18th Century, the deployment of armies

was usually conducted in like manner. In generalised terms an army would

march onto the battlefield, usually from the left, in a number of columns

of battalions, usually one column for each line of battle, each battalion

usually, though not necessarily, in strict hierarchical order within the

column. On reaching the place where the line of battle was to be formed,

the column wheeled 90 degrees to the right and marched parallel to the

enemy until the right of the alignment had been reached by the lead

battalion.

Each individual battalion was itself in column open to deploying

distance, each rank marching in open order for reasons of dressing already

discussed. This meant that the column of battalions was longer than the

line of battle it was intended to form, some two to three times. On

reaching the right of the line a signal would be given, the ranks closed up

and the distances between sub-units adjusted. The sub-units had to remain

at deploying distance, however, because in the next movement they would

wheel left simultaneously, forming the continuous line of battle .[12]

The disadvantage of this method is obvious in that it presented

the flank of the army to the enemy during the process of deployment.

Deployment in the absence of cadence was also extremely slow, it taking

hours to deploy an entire army. Because deployment was slow it had to be

conducted at such a distance as to prevent the possibility of surprise

whilst doing so. This meant literally miles from the enemy. [13]

So, the army is now deployed, in two, sometimes three, lines,

with very little depth or operational reserves, something like 300 paces

apart but close enough to provide mutual support, probably with the

cavalry on the flanks and artillery supporting the infantry lines. There

were essentially two things it could then do - receive an attack or deliver

one. In simple terms attacks were usually delivered along the entire

length of the line but lack of cadence meant that the complicated

manoeuvring, which increasingly distinguished warfare from the late 18th

Century onwards, was simply impracticable. A bit like a clockwork toy,

once having been wound up and pointed in a particular direction, the was

little possibility of doing anything else. Warfare was stereotyped and

predictable.

The next important development has already been alluded to -

the use of cadence marching. At the risk of being repetitive, cadence

marching was absolutely critical. Without the beat of a drum, or the time

being indicated in some other way, it is simply not possible for soldiers to

march in step for any length of time. Completely and utterly impossible.

It might be appropriate at this point to describe what cadence

marching was like in those, and Napoleonic, times. It was executed in

similar fashion to the modem British army's slow-march, arms remained

still by the side, legs straight and the toes pointed so that the foot

remained parallel with the ground. Most Napoleonic cadences were

not very much faster, indeed, the quickest in general use in those days,

approximately 120 paces to the minute, is not fast at all by modem

standards.

A contemporary instruction for the soldier reads thus,

The instruction concedes, however, that

Wonderful stuff. Try walking down hill on your toes, or, indeed,

uphill on your heels! The concession to bending the knee is of interest

though, for it demonstrates that the difficulty of rapid movement with it

locked was well recognised. Once bending the knee is allowed, the faster

cadences become less of a problem.

A plate from the Westphalian army's translation of the French

1791 regulations, identical with the original French version and used here

forease of reproduction, shows the style of marching at this period. It is

reproduced at Figure 1. [15]

Cadence

With cadence came the ability to maintain a universal number of

paces in a minute, increase them, or decrease them, as need be, according

to the rhythm given. Essentially, it enabled ranks to march in close order,

dressing could be maintained more easily and over much longer distances,

and the process of deployment was speeded up because there was no longer

any need to close-up open ranks before wheeling. It also meant that the

length of the column, be it of a single battalion or of multibattalion size,

was the same as it was when in line.

So, a battalion column marching onto the battlefield still did

open to full interval, to enable the wheel of sub-units for parallel

deployment, but the ranks and files of the sub-units now marched in close

order, with something like a pace between them, rather than the four, or

thereabouts, previously. The columns were, therefore, shorter and more

manoeuvrable and the time saved in deployment meant that although the

principles of parallel deployment remained the same, it could be executed

much closer to the enemy, at approximately 2,000 to 1,500 paces.

Time is a commodity so valuable in battle that the importance of

cadence marching, and with it close order ranks, cannot be overstated.

Marching in step with close order ranks increased speed and

manoeuvrability. Speed and manoeuvrability meant surprise, another

priceless commodity, manifested in the Prussians' operational use the

oblique attack, be it in line or echelon of battalions. Without cadence and

all that it bestowed, the oblique attack would have been quite impossible to

execute, indeed, it was difficult enough with it and performed, it would

seem, on far fewer occasions than legend would have us believe.

The approach march described above remained, however, an

extremely difficult thing to choreograph. Battalions had to be arranged in

the same order in the column as they would be when in the line of battle,

thus the senior battalion of the senior regiment lead the column when

deploying from the left, so that it would occupy the right of the line.

Intervals between the marching battalions had to be maintained so that no

compromise of the line would occur upon deployment. The operational

plan was not susceptible to change and, as a consequence, had to be

conducted without interruption to its conclusion. A failed attack

frequently meant a lost battle.

The Prussians of Frederick the Great were both tactically and

operationally superior to their opponents, the record speaks for itself. The

reasons lay partly in the diverse nature of the human material. In very

simplistic terms, in order to order to prevent desertion it was necessary to

maintain discipline. Part of the maintenance of discipline involved drill,

lots of it, which in those days, unlike now, was inextricably linked to

tactics. It meant that the Prussians became extremely skilled, perhaps, it

could be argued, by accident rather than design. They fought the way they

did, because they could. Paret puts it thus,

The men moved instinctively and the command element, the

officers and NCOs, that vital part of battalion integrity, were thoroughly

familiar with what was required of them, which, however, was not actually

very much in comparison with later times.

A frequent criticism of Prussian doctrine is to the effect that it

stifled individual initiative at the tactical level of command. Indeed, it

could also be argued that it had a similar effect on operational art at

subordinate levels, This, in my view, rather misses the point. Individual

initiative was about as necessary to l8th Century tactical and operational

art, as it is to formation ballroom dancing.

To review what we have so far then. Parallel deployment was

essentially unchanged, tactics remained exclusively linear and relatively

simple. Cadence marching, however, had made the whole process faster. A

by-product of cadence was the ability to march in step to a uniform pace

with close order ranks, which resulted in further increases in speed of

deployment and manoeuvre. Deployment was able to take place closer to

the enemy and, therefore, the advance to contact, still in line, was over a

shorter distance.

It may be pertinent at this point to mention infantry firepower.

Although cadence was also applied to the manual of arms, which speeded

it up, musketry remained what it always had been, a relatively inefficient

weapon system. Even the Prussians with their theoretical one round every

eleven seconds rarely seem to have maintained this rate for long, if at all,

and seemed to have discharged no more than three rounds a minute in

practice. [17]

Bearing in mind the steady decline in the powers of his infantry

towards the latter part of the 18th Century, one is tempted to suggest

that the legendary Frederican musketry might yet be another myth. It has

certainly been said that even in its hey-day, the high rates of Prussian

musketry also meant less accuracy and the object seems to have been

intimidatory as much as anything else. [18]

Napoleon concurred,

This confirms, yet again, what has been said by numerous other

contemporaneous, and earlier, comentators, that the first volley was the

one that really counted, to which it is worth adding that these same people

were also of the opinion that firing first, but not decisively, being left with

unloaded muskets whilst one's enemy had yet to fire, was likely to result in

almost certain disaster. Clearly the decision when to fire was not one to be

taken lightly!

There would, nevertheless, be no fundamental changes in

methods of delivering musketry throughout the remaining years Qf the

black powder smooth-bored era. They had already changed as much as

they would, largely being simplified and tending more and more away from

comparatively complicated methods to firing by ranks, independent firing

becoming more prevalent once initial volleys had been exchanged. Indeed

it is possible to argue that musketry must have become even less effective

during the middle and later Napoleonic period, perhaps the least effective

of any during the black powder era, with mass conscription and relatively

poorly trained infantry.

All About Movement

All the technological advances had already been made, iron

ramrods, conical touch holes, bayonets and so on, nothing new would

appear until the introduction of percussion ignition some time after

the close of the Napoleonic period. Although 18th Century musketry

may well have been improved by the application of cadence, the spin-offs

of marching in step and close order ranks had no bearing on firepower per

se. These were all about movement.

Close order ranks had always been used for firing for obvious

reasons. Clearly it was not a good idea to have a black powder muskets

discharged two or three feet behind one's left and right ear, in the hope

that the ball will pass between your head and those of the soldiers beside

you.

What marching with close order ranks did for musketry was

simply to allow the first volley to be delivered more quickly, in so far as it

was no longer necessary to halt and close-up open ranks first. Once all

armies marched with close order ranks, as they did by the time of the

Napoleon period, any tactical advantage was lost.

The tactical gap between archetypical 18th Century warfare

and early 19th Century warfare now needs to be crossed. Two separate

developments had begun to take place. The first, predictably, was

Prussian, and principally at the tactical level. The other, at the

operation; level, occurred in France. When the two were combined, the

seeds what we may call Napoleonic tactical and operational art were

sown.

With the discovery of cadence, minds were eventually set to

examine evolutions which might make use of the advantages it bestowed

principally ways of deployment that avoided presentation of a flank to

the enemy, unavoidable in the parallel method. The answer was

perpendicular deployment.

At the tactical level this was accomplished by either the quarter

wheel of sub-units and diagonal march onto the alignment from colum

at deploying distances, or the flank march of files en droir from close

column, or a variation of one or other of these two methods. The

principles, however, also began to translate themselves into the

operational level where an entire army could use perpendicular methods

to deploy into line. A column of battalions could now deploy its

battalion by use of a diagonal march, in exactly the same way that the

battalion deployed its sub-units by means of the quarter wheel.

[20]

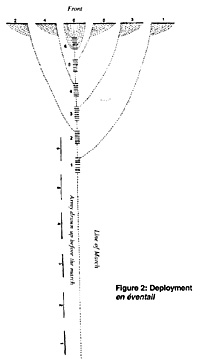

A further development was perpendicular deployment of battalions

from a column evantail (in the shape of a fan), where alternate battalions

marched diagonally left and right onto the alignment. A diagram is at

Figure 2. [21]

Difficulty with Perpendicular Deployment

The difficulty with perpendicular deployment at the operational

level was that it required much greater skill and precise timing than

parallel deployment. It is clear that with latter there was less danger of

battalions loosing dressing between each other or their places in the line as

the main column marched onto the new alignment, they simply followed

each other crocodile fashion. With perpendicular deployment, however, a

clear reference point was needed as each battalion marched diagonally, and

individually, onto the new alignment. This was usually provided by an

officer who posted himself on the right flank of the alignment on which

his battalion was supposed to deploy. The difficulties of choreography are

obvious and magnified in the en eventail manoeuvre because here the

battalions, if seniority was to be maintained in the line, had to be arranged

differently in the column. The great advantage of perpendicular

deployment en eventail, however, is obvious in that a column could now

march onto the battlefield from the centre and was not confined to one or

other of the flanks.

All this, however, did not alter the fact that it was designed to

facilitate one thing and one thing only. Ultimate deployment into the

familiar linear order. The fact of the matter is that although speed of

deployment was further increased, the associated difficulties of

perpendicular deployment at operational level, so long as the importance

of linear tactics remained paramount, were such that it was not practised

often. Nosworthy identifies only three occasions when the Prussians

attempted it, and not at all after 1757. Parallel deployment, despite all its

disadvantages, remained the principal operational method of deployment.

[22]

Perpendicular methods, however, could be used tactically by

individual battalions to 'ploy' quickly into column to avoid obstacles during

the march to contact, and to deploy back into line again once they had

been passed, in a manoeuvre called breaking. Descriptions of how and

when to do this are piven specifically in all regulations subsequent to

approximately 1756 [23] and are

evident in both the Prussian 1788 regulations and 1798 instructions [24]

So, the possibility now exists of battalion columns, albeit non-

tactical in nature in so far as soldiers could not fight in them, within the

tactical environment.

How prevalent was the Prussian use of columns generally

though?

Yorck is quoted, in the context of his instructions for the

Prussian Jdger, as saying that all deployment should be conducted from

company or battalion columns, but, as late as 1800, according to Parer

this evolution although "basic practice in the French anny, was new to

Prussia." [25]

It does not seem likely to me that Yorck would have issued an

instruction to his soldiers that they did not know how to execute.

Battalion columns, and deployment from them, are, indeed, described in

the 1788 regulations as we have already established. What certainly did

not exist was an official doctrine for using them in conjunction with line

and skirmishers in the classic 'Napoleonic' fashion and perhaps this is what

is being alluded to. Despite the efforts of Prussian refonners it is true to

say that although some change had already taken place and the process

was continuing, the Prussians fought the 1806 campaign with a tactical

doctrine in which the line remained the dominant formation.

We are getting a little ahead of ourselves though. Lets return to

the latter half of the 18th Century for concurrent with the Prussian

tactical innovation and experiment, tactical and operational experiments

were also taking place in France.

Towards the middle of the century French military thought had

concentrated into two distinct camps. The first contained the followers of

what became known as ordre mince, the other those of ordre profond.

The former were the conservative advocates of the old linear order, the

latter advocates of columnar formations manifested in the multi-battalion

columns of Chevalier Folard designed, apparently, to suit the charateristics

of the French soldier and "infinitely better suited for shock and coups de

main than for standing still and firing." [26]

To which one is tempted to point out that the Prussians tended

not to stand still and fire.

It is in the smaller, more flexible, columns of Maurice de Saxe's

legion, however, and the appearance, at approximately the same time, of

a light infantry element in the order of battle of the French line infantry

battalion, that one finds the embryonic tools with which 'Napoleonic'

operational art was conducted, even if the doctrinal seeds of it had yet to

be sown. [27]

It was not until 1749, however, that the French adopted cadence

but despite having done so, the French continued to march with open

ranks, the advantages of cadence marching not, apparently, being

recognised. In brief, although the French anny attempted to emulate

Prussian linear methods, and improve upon them by incorporating

columnar devices of the order profond school, it was not the practical

equal of its theoretical aspirations. It was simply not trained to the same

high standard as its peers, particularly the Prussians.

Still unfamiliar with the various innovations of the 1755

regulations, on 5th November 1757 the French army and its Imperial allies

were surprised and decisively defeated by the Prussians at Rossbach, a

defeat so cheaply obtained that Frederick would refer subsequently to the

French as "the quarry of Rossbach", such was the contempt in which they

were held. In the aftermath, naturally enough, the French set about

improving their army and the 1764 regulations whilst further embracing

the Prussian methods incorporated the single battalion assault column for

manoeuvre, this in turn resulted in what would later become notorious as

ordre mixte, simply a mixture of the order profond and ordre mince,

appearing the French repertoire. [28]

The French, nevertheless, remained comparatively unskilled in

deploying and in an attempt to overcome this defect, the influence of

Mardchal de Broglie resulted in the French adopting deployment from a

number of smaller columns, rather than the two large ones that had been

the custom previously. Although the French use of a number of smaller

columns increased the speed of deployment, it also made it more

complicated to perform.

It became necessary for reasons of consistency

and familiarity that these columns be formed from the same battalions, at

least for the duration of a campaign. Thus, each of these small columns

became a 'Division', with its own integral artillery, the component parts

of which became used to serving together. [29]

A new operational formation had been arrived at, more, apparently,

by accident than design. It was still, however, intended to facilitate linear

deployment.

In 1772 Guibert published his famous Essai. In it, two principal

formations were proposed. The three rank line, which remained the

principal fighting formation, and the column which now was to be used

as the manoeuvre element and, if necessary, a means of assault. He also

proposed that every infantryman should be equally capable of fighting in

formed and skimiish order, thus removing the need for specialist units

and, indeed, specialist elements within the battalion. None of the for-

mations proposed by Guibert were new. None of the methods of

converting from line to column and vice versa were new. All had their

origins in Potsdam. In 1778 the French army actually went to the trouble

of holding exercises where the column was pitted against the line, in an

attempt to resolve, not only the efficacy of the two formations, but

whether large columns were preferable to small battalion columns

advocated by Guibert. [30]

No longer was the precise choreography of linear doctrine

appropriate, with its lack of depth and single effort along the entire front.

This was to be replaced by an attacking element consisting of a mixture of

columns and lines as appropriate, supported by further columns, in depth,

ready to manoeuvre, exploit or reinforce. This is order mixte, not the

misleadingly stylized single battalion line flanked by a battalion in column

on each flank, so often used to represent the concept in modem popular

works.

There was no longer any dogma in the context of formations to

be adopted, this was entirely dependent upon the initiative of the local

commander based upon enemy, terrain and circumstances. No longer was

the attack to take place along the entire front as had been the case in linear operations, it now took place selectively, first at one point, then

another, as need be, keeping the enemy off balance. At the critical

moment force, in the shape of an operational reserve, was concentrated at

a vital point and the breakthrough made.

What this needed to be successful, in addition to fine judgement,

was command and control at the operational level of a kind that was

entirely absent in the linear system. What the army corps system offered,

in addition to a much more flexible operational organisation generally, was

a properly consititued operational chain of command from the army

commander down to the brigade commanders. In order to be successful,

however, it required the kind of initiative in subordinates at operational

level that was unnecessary in the strict choreography of the linear system

and, therefore, entirely absent from it.

Command now devolved upon Formation commanders in a way

that it never had before. Not only was the necessary operational chain of

command system absent in armies trained in the linear doctrine of the

Ancien Regime, the operational commanders were simply incapable of

the kind of individual initiative and lateral thinking displayed by their

French peers, not because they were stupid, simply that it had never been

expected of them before and they were not prepared for it.

What can be said of the allegedly radical French 1791

regulations? Simply this. They were the product of Prussian practice and

experimentation during the last half of the 18th Century. What then of

Guibert? His contribution must not be underestimated and was undoubtedly

this. He defined a tactical doctrine, already emerging in French late 19th

Century tactics, that used existing Prussian drill methodology in a way

that had not been envisaged. The ultimate result, it could be argued, were

the 1791 regulations, but, and I cannot emphasise this too much, these

were not a radical departure in terms of drill from anything that had

preceded them. It was the way that the tool was used, not the tool itself.

To return to the basic question about the willingness of the

French to manoeuvre in column under fire, it is impossible to define the

differences in doctrines in such simplistic terms. Prussian 18th Century

doctrine allowed columns in the tactical environment, but principally as a

temporary 'ployment' to avoid terrain features. In general terms, however,

linear doctrine at operational level, as practised by the Prussians, called for

an attack in line on a broad front with little depth, by the entire available

force and with comparatively few, if any, operational reserves.

Napoleonic doctrine called for whatever formation was

appropriate to solve the tactical or operational problem, the attack

being concentrate on a narrow front, switched from point to point as

appropriate, conducted in much greater depth and with substantial

operational reserves.

Typically this meant manoeuvre in column throughout the

tactical environment deploying into line if need be, essentially where

the enemy had not been intimidated into flight and ideally outside the

effective range of musketry, an advance to within musketry range and

exchange of fire then took place followed by 'ployment' back into

column and further manoeuvre necessary. This was supported by further

columnar formations, in second 'line', ready to reinforce and exploit

success, and an operational reserve. If linear doctrine was analogous to

formation ballroom dancing, this was 'Rock and Roll'.

It is also necessary to point out that in the linear system

operatio command was centralized in the hands the army commander.

This me that, because no operational chain of command existed such as

found the army corps system, orders had to be passed direct from the ar

commander, in detail, virtually to individual units. This was slow.

In army corps system, command was decentralized. In

generalised terms, orders given to Corps commanders would be broadly

stated, what would call mission orientated orders today, and having

received them, Corps Commanders would be responsible for conduct of

their particular mission and would, in turn, give their Divisional

command equally broadly stated orders. The Divisional commanders

would likewise, giving orders to their Brigade commanders who actually

patrolled the fighting units. [31]

The benefit of the comparative speed transmission of orders,

both on and off the immediate battlefield, speed of reaction and

flexibility on it, was that of time and, therefore manoeuvrability and

surprise.

It was this ability to translate an operational plan into

operational reality with unprecedented speed that lay at the heart of

Napoleonic tactical and operational art and "was the essential secret of

French mobility on which in turn Napoleon's strategy depended .. ... the essence of which was, that no matter what the enemy did, or did not do, Napoleon was certain to unite a

numerical superiority against him". [32]

The concept, however, that Napoleon, or any other army

commander, was actually able to influence what happened tactically once

contact had been made is illusory.

Divisional commanders, and to an even lesser extent Corps

commanders, did not need to concern themselves with the minutiae of

tactical decisions on the battlefield. I can do no better than to quote

Richard Riehn again,

Before concluding, it is necessary to point out that the effects of

the campaigns between 1805 and 1807 meant that the French infantry was

never able to repeat such tactical excellence again and, indeed, a steady

decline was seen thereafter. This was parallelled by a steady

improvement in the capability of France's opponents as they too

adopted the new tactical and operational concepts, even if they never

did quite equal the flair of the French at the operational level.

In an attempt to describe the developing tactical and

operational doctrine of formed infantry, this article has ignored

the contribution that skirmisher tactics had on the Napoleonic

battlefield, a subject worthy of a study in its own right. It also

completely ignores the tactical changes that took place in the other two

arms, both of which affected the way the infantry went about their

business; the operational use of artillery on the Napoleonic battlefield and

cavalry superiority, the vital ingredient to the success of offensive

operations.

What I hope it has done is illustrate the point again that

although drill and tactics were so closely connected at this period as to

blur the distinction sometimes, the former, and the formations

and conversions it allowed, really did not change much during the 50

years or so that preceded the Napoleonic period. What did change, out

of all recognition, was the tactical application and in this context the

two are separate and distinguishable.

I make no apology for closing with a final quote from Brent

Nosworthy's remarkable book [35].

There are numerous histories of the armies and campaigns of the

period, Fortescue, Jany, Stein, Wrede and so on, not to mention histories

produced by Continental General Staffs, essentially as text books for the

instruction of officers. Those dealing with the narrower subject of tactical

and operational art, and doctrine, however, are probably less prolific. The

following is a list of those either recommended for further reading

or consulted during the preparation of this article, and which are either in

print or can be obtained through public library services. It is not exhaustive

by any stretch of imagination, nor should it be imagined that the only

books on the subject are in English.

The list is a reflection of the limitation of my personal 'library' in

which context I should point out that I do not own a copy of Colin. It is

worth trying to get sight of it through the local library since it is

undoubtedly the most famous analysis of the subject. It is possible, and lots

of fun trying.

First you will be met with incredulity, it being in a foreign

language! Being more than a few years old also adds another dimension!

Persevere, it will eventually arrive. Do not expect to be allowed to take it

home though.

L'infanterie au XVIlle siecle: la tactique. Jean Colin. Paris 1907.

This is the best known and most frequently quoted modem work

on the subject of infantry tactics in the context of the Napoleonic period.

Oriented towards an explanation of the tactical phenomenon that was the

French infantry during the hey-day of the Grand Army, it could be argued

that Colin gives Guibert rather more than his due at the expense of

Prussian contribution to tactical change. This book remained until recently

in a class of its own and is, nevertheless, still the standard work on the

subject. Unfortunately, it is useless without some knowledge of French.

Don't worry though, get a copy of Nosworthy. See below.

A Review of the History of Infantry. E.M. Lloyd. London

1908. More than a third of the book is devoted to the

18th Century and Revolutionary/Napoleonic period. It does not

contain the specific kind of detail found in Colin and is painted

on a much larger canvas. It provides, nevertheless, a balanced and

accurate overview of the strengths and failings of the various

nations' am-ties. One wonders how certain subsequent 20th

Century authors arrived at some of their conclusions about

the Prussian army in 1806, for example, and column and line in

the context of the British in the Peninsula. The bibliography is also

comprehensive and very useful. It is a very competent, albeit concise,

account of how tactical and operational art evolved in the way that it

did, and why, from ancient times to the early 20th Century. Its broad

appeal would probably make it a worthwhile reprint.

The Background of Napoleonic Warfare. Robert Quimby.

New York 1975.

This work is very well known. It could almost be described as an

English language summary of Colin. It is long out of print and although

there are more recent and better books on the subject, it is worth having

if one crops up. Don't shed any tears if you can't find one though. Ross and

Nosworthy are just as good, the latter better. Alternatively it can be

obtained with relative ease through the public library service. Another

worthwhile reprint I would have thought.

From Flintlock to Rifle, Infantry Tactics 1740-1866.

Steven Ross. London 1979.

A small book whose size does not reflect its usefulness. It bridges

the tactical gap from late l8th Century to early 19th Century infantry

tactics in an easily assimilated and readable fashion. It is also very useful in

the context of the subject subsequent to the Napoleonic period. It

does, nevertheless, give Guibert unambiguous credit for innovations that

are rightly Prussian; the influence of Colin I suspect. It is a useful primer

which still appears in lists.

Tactics and Grand Tactics of the Napoleonic Wars.

George Jeffrey. Brockton, MA 1982.

This book goes beyond the subject of infantry tactics and includes

chapters on the other arms. It explains with the use of numerous diagrams,

which makes it all the easier to understand, and also deals with the

operational (grand tactical) levels of command in similarly easily

understood detail. It is dated not without considerable flaws. Guibert is again

given credited for innovations that are not his and the French 1791

regulations are used, apparently, to the exclusion of others. More

importantly, the so called "Prussian system" it compares with the so called

"French system", is essentially that of the period prior to approximately 1750. It completely ignores the Prussian tactical innovations subsequent to

that date, those which so influenced Guibert and other French advocates of

the ordre profond school and, indeed, the 1791 regulations. Use with great

care.

The Anatomy of Victory, Battle Tactics 1689-1763.

Brent Nosworthy. New York. Undated.

Do not be deceived by the title of this book, it really is about the

background to Napoleonic warfare and concludes with a chapter that

touches on the subject specifically. It describes in detail the evolution of

18th Century tactical doctrines, together with examples of the drill

involved and accompanied by explanatory diagrams where relevant. It is

shows, without doubt, that the infantry drill and formations used by the

French during the Napoleonic wars, had their origins in the Prussian

innovations of the latter half of the previous century. This is simply an

outstanding book and quite the best on the subject since Colin. It is in

print now. Nobody who has the slightest interest in how the foot soldier

went about his business should be without this book. I cannot recommend

it too highly. Get one.

Yorck and the Era of Prussian Reform 1807-1815. Peter

Paret. Princeton, NJ 1966.

The title of this book is also deceptive and treats the entire

period from the late 18th Century, through the debacle of 1806 to the

end of the Napoleonic period. It is not a biography. The narrative is about

Ludwig von Yorck only in so far as he was inextricably involved in the

evolving doctrinal and organisational reforms of the Prussian army during

the Napoleonic period. As such it is the story of the Prussian army of the

period too. It is the only worthwhile English language study of the subject

still, I think, in print.

Peninsular Preparation, The Reforms of the British

Army 1795-1809. Richard Glover. Cambridge, 1963.

If there was a single army that went from the ridiculous

to the comparatively sublime during the period it has to be the

British. Richard Glover does for the British army what Peter Parer

did for the Prussian. Lacks a bibliography, which is a shame. Another

standard that ought to be on every bookshelf. Reprinted by Ken Trotman

in 1988.

Napoleon's Great Adversaries, The Archduke

Charles and the Austrian Army 1792-1814. Gunther E.

Rothenberg. London, 1982.

A poorly named title that implied the promise of a series but

which never materialised. It should have been called 'The Archduke

Charles and the Reform of the Austrian Army', or something similar. A

well known work, and justly so, it compares with Paret and Glover,

forming, to all intents and purposes, the third volume of a 'trilogy'. It has

become the standard starting point in the English language. It is due for a

reprint in 1995 1 think. Get a copy. There is nothing else readily

available on the subject in English which is worthwhile.

Von Austerlitz bis Koniggratz, Osterreichische

Kampftaktic im Spiegel der Reglements 1805-1864. Walter

Wagner. Osnabruck, 1978.

An extremely well researched comparative study of the

respective Austrian regulations and their tactical application.

Chapter 1 deals with the Napoleonic period, containing a

comparison between the 1769 and 1807 regulations, which shows,

more or less, that the latter was not radically changed from the former.

Useless if you do not have at least a little German. In print.

The Campaigns of Napoleon. David G Chandler. London,

1966. I don't suppose there are many who do not own of

have not heard of this work. Although it is now dated in parts, it

remains the general starting point for the English reader. It also

includes useful chapters on the art of war during the period.

The Jena Campaign. F. N. Maude. London, 1909.

This campaign history, whilst being far and away the best

there is in English, also contains one of the most balanced discussions of

the tactical doctrines of the respective protagonists as has been written

anywhere. Again one wonders how modem authors arrived at their

conclusions in this context. This one is well overdue for republishing. It

is a shame that Maude's title on the 1813 campaign was chosen for a

recent reprint since it is not so useful.

1812: Napoleon's Russian Campaign. Richard K Riehn. New York, 1990.

If I was to recommend a single account of the 1812 campaign, it

would probably be this one. It also contains as succinct and readable at

analysis of Napoleonic tactical and operational art as you will find

anywhere. Still in print, I think. Get one if you can.

[1] 1 Jeffrey, George. Tactics and Grand Tactics of the Napoleonic Wars. Brockton, MA, 982. pp42-44.

"tread neither on his heels or his toes but to bring his foot

flat down with a straight knee, so as to leave the mark of the full foot upon

the ground. The knee may indeed be somewhat bent in the deploying

march in order to allow the files to lock up closer".

"In ascending a hill the toe will be set down first, in

descending a hill the heel, circumstances which are already known as

exceptions to the general Rule"

. [14]

Figure 1. Positions adopted by Soldiers Under Arms

and when Marching

Figure 1. Positions adopted by Soldiers Under Arms

and when Marching

"Close linear formations seemed to answer most

adequately not only the requirements of tactical control and effect, but

those of disciplinary control as well"

. [16]

"There is no necessity for firing veryfast; a cool well

levelledfire with pieces carefully loaded is much more destructive and

formidable than the quickest fire in confusion"

. [19]

Figure 2: Deployment en eventail

Figure 2: Deployment en eventail

"The commander in chief might set the tasks for his corps

and division commanders, but it was left to the brigadiers to actually carry

them out upfront. They were the men who made the final dispositions of

their combat elements and who decided in precisely whatfashion a given

objective was to be attained"

.

[33]

"each battalion, each brigade - every tactical unit - was an

articulatedfighting entity that could change its shape and the direction of

attack virtually at will. Most importantly, these constituent units of the new

order were in the hands of tactically self-reliant officers who knew how to

make use of this flexibility and how to use their own judgement in

adapting themselves to whatever a situation demanded. It is impossible to

over-emphasize this point"

. [34]

"Napoleonic warfare on the battlefield was the

amalgamation of the French grand tactical (operational) aspirations as

displayed during the Seven Years War with the Prussian tactical systems

that had evolved between 1748 and 1756."

Bibliography

References

[2] Chandler, David. The Campaigns of Napoleon. London,

1966 pp 133-201 and pp 332-367.

[3] Chandler. op. cit. pp 136-143.

[4] The Collins Concise Dictionary. London, 1986.

[5] The Concise Oxford Dictionary (New Edition). Oxford, 1978.

[6] Chandler, David. Atlas of Military Strategy, The art, theory and practice of war 1618-1878. London, 1980. pp7-11.

[7] Nosworthy, Brent. The Anatomy of Victory, Battle Tactics 1689 - 1763. New York, n. d. ppl02- 103.

[8] Ross, Steve. Flintlock to Rifle, Infantry Tactics 1740-1866. London, 1979. pp36-37.

[9] Jeffrey. op. cit. pp27-28.

[10] Lloyd, EM, Col. A Review of the History of Infantry. London, 1908. pp 182-183.

[11] Nosworthy. op. cit. p252.

[12] Lloyd. op. cit. ppl56-158. Jeffrey. op. cit. pp105-108. Nosworthy.

op.cit. pp 65-77.

[13] Nosworthy. op. cit. p287

[14] Instruction for the Infantry. Berlin, 11th March 1798. p10.

[15] Reglement das Exercitium und die Manbvres der Franzesischen Infanterie betreffend, vom Isten Ausgust 1791. Aus dem Franzbsischen fur die Koniglich-Westfdlischen Regimenter.Braunschweig, 1812. Die Soldaten-und Ploton-Schule, PII, pvii.

[16] Parer, Peter. Yorck and the Era of Prussian Reform,

1807-1815. Princeton, NJ, 1966. p16.

[17] Ibid. p14.

[18] Lloyd. op.cit. p158 (discussing Kriege Friedrichs des Grossen, Abtheilung fur Kriegsgeschichtliche (Military History Section of the Prussian General Staff). Berlin, 1890-1893)

[19] Napoleon 1. Correspondence. 1870. Vol 31, p430. (quoted in Lloyd).

[20] Nosworthy. op. cit. pp243-250.

[21] Dalrymple, C. A Military Essay. London, 1761. p185 (as

reproduced in Paret).

[22] Nosworthy. op. cit. p249.

[23] Nosworthy. op. cit. p249

[24] Instruction for the Infantry 1798. op. cit. pp2-27.

[25] Parer. op. cit. p105.

[26] Lloyd. op.cit. p142.

[27] Marshall-Cornwall, James. Napoleon. London, 1967. p27.

[28] Nosworthy. op.cit. pp334-337.

[29] Nosworthy. op. cit. pp329-331.

[30] Ross. op. cit. p38.

[31] Maude, F.N. The Jena Campaign. London, 1909. p46.

[32] Maude. op.cit. pp47-48.

[33] Riehn. op.cit. p94.

[34] Riehn. op. cit. p126.

[35] Nosworthy. op. cit. p352.

Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #22

Back to First Empire List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1995 by First Empire.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com