During the spring of 1800 Napoleon Bonaparte’s Army of the Reserve was campaigning against the Austrians in Italy. The culmination of which was the decisive victory at Marengo. Much has been written about this, not least by the Great Man himself. Regrettably Napoleon’s own interventions in the history books by way of two rewrites of the battle has tended to steal the thunder of the man who actually won the battle, and died during it’s course: General Louis Desaix.

Having won at Montebello, Bonaparte was almost excessively contemptuous of the Austrian troops he faced and particularly their commander, the 71 year old Field Marshal Melas. By June 13th Bonaparte was carrying out what he believed to be a winning strategy by means of a drive on Genoa, which had recently been lost by Massena. It would appear that he convinced himself that Melas had no stomach for a fight. Scouting reports suggested Melas was concentrating around Alessandria and further reports specifically requested by Bonaparte told him that the bridges over the Bormida river had been destroyed.

With this information to hand, Bonaparte assumed the following. Firstly, that Melas would not fight for Alessandria, primarily on the reasoning that he had not had time to concentrate properly. Secondly, with a supporting British fleet controlling the Mediterranean Sea, Melas could be expected to retire on Genoa. Accordingly he planned to cut off Melas by blocking his possible routes of withdrawal. Desaix with two divisions was dispatched to block the road to Genoa whilst an overstrength brigade was sent to Piacenza, at the Po River crossing.

In fact, contrary to all Bonaparte’s expectations Melas had amassed 34,000 troops which he threw at the Divisions of Victor and Lannes, who with other scattered formations totalled only about 15,000 men. Victor was screening the Bormida opposite Ales-sandria and having won a brief skirmish around Marengo earlier in the day he was reasonably confident of a peaceful night. His two divisions were commanded by Gardanne and Chambarlhac, a total of 8,800 infantry and 1,000 cavalry. All he had in the way of artillery were two guns captured during the skirmish on the 13th.

Austrian Attack

At dawn on June 14th Melas’ attack swept over the two bridges which Bonaparte believed were not intact. Luckily for the French, traffic jams on a converging road slowed down the movement meaning that it was 8 a.m. before the Austrians engaged Victor. Organising Gardanne to contain the assault whilst Chambarlhac came up, Victor got off a dispatch to Bonaparte informing him of the situation. It must be said at this point that although Victor showed considerable poise in his handling of the initial surprise, that surprise was partly his fault, as he was aware of enemy movement shortly after midnight.

Gardanne sustained a traumatic hour of artillery bombardment before the Austrians were fully deployed. For around one hour Gardanne beat off all attacks until repeated use of fresh troops meant he was in danger of being overwhelmed. It should be pointed out that Gardanne’s initial position was covering only a half mile frontage, meaning that the enemy could not employ overwhelming numbers in the early stages. At 10 a.m. Gardanne was pulled back behind Fontanone Creek with almost 50% casualties.

The main central attack was to be carried out by the columns of Haddick, Elsnitz and Kain, 18,000 strong, launched directly at Marengo. Ott with another 7,500 was to attack Castel Ceriolo on the French right. Until mid-day, Gardanne and Chambarlhac repulsed all attacks. They were not helped by the fact that Bonaparte erroneously believed that this was indeed a full scale attack. He was still at Torre-di-Garofoli and only at 9 a.m. had ordered Lapoype's division to move off to Valenza.

Fatal Error?

By 10 a.m. Bonaparte had realised his potentially fatal error and with characteristic vigour proceeded to correct it. Lannes and Murat were ordered up to support Victor with the First Consul arriving on the field at about 11 a.m. He had sent out passionate appeals to his detached formations to return to him with all speed.

From noon for almost one hour the Austrians pulled back fraction-ally to regroup whilst Ott’s detached column continued its sweep wreaking havoc on Watrin’s division which had bee posted to contain it. Monnier’s division and the Consular Guard were sent to Watrin’s assistance around Castel Ceriolo. The French counter and the loss of Marengo itself both occurred around 2p.m. but the Austrian sledgehammer was halted whilst Melas awaited information on whether Ott’s attack had been successful. The problem for the French was that now they had no reserves whatsoever, and when the reconstituted Austrian assault went in before 3p.m. the French were driven back. It was at this juncture that Melas made a fateful and arguably treasonous mistake. He deserted the field.

This may appear to be putting it a trifle strongly, but consider the circumstances. Melas was certain that he was victorious, all bar the shouting. Carrying a very slight wound he determined to return to Alessandria for treatment and no doubt to bask in the glory of his achievement. He thus handed over battlefield command to his chief of staff, General Zach. What Bonaparte now knew, but which neither Melas nor Zach did know, was that help was at hand.

Even whilst the main Austrian assault was driving his army back-wards, Bonaparte was receiving Desaix at his headquarters with news that Boudet’s division was practically within spitting distance of the field. Shortly after he moved into the line supporting Lannes and Victor, and giving the men new heart, along with a few well-timed and well-chosen words from the Maestro himself. Then he attacked. Supported by excellent use of close support artillery, they stopped the Austrian columns dead in their tracks, and before they had a chance to recover Kellermann’s cavalry had torn into Zach’s left flank, capturing Zach and thousands of his crack grenadiers. The Austrian right col-lapsed and seeing the shambles Ott decided to withdraw rather than risk being cut off. It really was victory snatched from the jaws of defeat.

Moment of Glory

The moment of glory was perhaps soured by the death of Desaix, shot through the chest, although it may well be that Bonaparte was glad to be rid of a potentially capable rival, although he did write to Paris: “I am plunged into the deepest grief for the man whom I loved and esteemed the most.”

Austrian losses were 6,000 dead, another 8,000 captured along with 40 guns and 15 standards. French losses were about 6,000. Bonaparte’s after-action bulletin gave Desaix credit for the victory, in particular also mentioning Kellermann. It would appear, however that the First Consul was not completely satisfied with this version of events. In 1803 the mark II version was prepared, giving the future Emperor more of the credit. However, by 1805 Napoleon was still dissatisfied with the story, so he bumped up the enemy numbers to 45,000 men and 200 guns and gave Desaix conditional orders to return if he heard gunfire. Also now Castel Ceriolo was now held throughout the day by Carra St.Cyr’s brigade from Monnier’s division.

Still, no-one could ever accuse Napoleon of bad media relations. In fact, he is probably a shining example to royalty everywhere.

Notes on Wargaming Marengo

- Game Length.

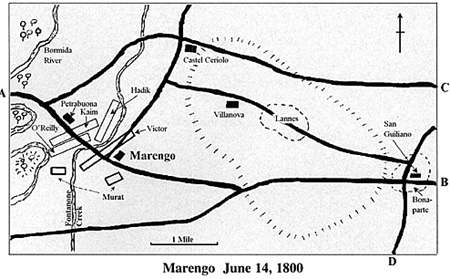

The map is drawn up to begin the battle at 10 a.m., Gardanne’s Division having fallen back to Marengo village. The battle should continue until nightfall at 8.30 p.m.

Terrain.

All villages are light in construction. The Bormida River is unfordable, although the Fontanone Creek may be traversed normally. North of Marengo, the crossing should be more difficult due to the sharper banks. The large central hill has gentle slopes.

Deployment.

Bonaparte’s Consular Guard and his Artillery Reserve should begin encamped around San Guiliano. The Austrians commanded by Ott may arrive at entry point A on move 1. The French deploy first.

Troop Arrivals.

Boudet’s Division of Desaix arrives at entry point B at the 12.30 p.m. move.

Desaix and his own division arrive at entry point D on the 4 p.m. move.

Rivaud’s cavalry brigade arrives at 5.30 p.m. at entry point C.

Victory Conditions.

Somewhat obvious. Both sides are seeking a decisive field engage-ment to destroy their opponent's ability to make war. If at the end of the battle one side can claim this, he has won. All other results merit the term - draw.

French Republican Forces under First Consul Napoleon Bonaparte

Army of the Reserve:

General Berthier

Victor's Corps

General Gardanne's Division

Brigade: General Gardanne

- 44th Demi-Brigade 1750

101st Demi-Brigade 1800

102nd Demi-Brigade 500

Division: General Chambarlac

Brigade: General Malher

- 24th Demi-Brigade Legere 1800

43rd Demi-Brigade 1900

Brigade: General Rivaud

- 96th Demi-Brigade 1600

Lannes' Corps

Division: General Watrin

Brigade: ???

- 6th Demi-Brigade 1100

40th Demi-Brigade 1700

Brigade: General Gency

- 22nd Demi-Brigade 1200

Brigade: General Mainony

- 28th Demi-Brigade 1000

Desaix's Corps

Division: General Monnier

Brigade: General St. Cyr

- 19th Demi-Brigade Legere 900

Brigade: General Schilt

- 70th Demi-Brigade 1400

72nd Demi-Brigade 1200

Division: General Boudet

Brigade: General Musnier

- 9th Demi-Brigade Legere 2100

30th Demi-Brigade 1400

Brigade: General Guesneau

- 59th Demi-Brigade 1800

Combined Grenadiers & Chasseurs of the Consular Guard 1bn - 800

Murat’s Cavalry

1st Brigade: General Kellerman

- 2nd Cavalry Regiment 120

20th Cavalry Regiment 300

21st Cavalry Regiment 100

- 1st Dragoons 450

8th Dragoons 328

9th Dragoons 428

3rd Brigade: ???

- 12th Chasseurs a Cheval 345

11th Hussars 340

6th Dragoons 110

4th Brigade: General Rivaud

- 21st Chasseurs 359

12th Hussars 300

5th Brigade: General Duvignaud

- 3rd Cavalry 120

1st Hussars 120

Consular Guard Cavalry 369 in total

- Grenadiers a Cheval 1sqn

Chasseurs a Cheval 1sqn

It is believed that Napoleon had 41 Cannon available of which 8 were with Desaix.

Austrian Army under General Melas

Advance Guard: F.M. Quosdanovich

- Bach Light Infantry Battalion 300

Am Ende Light Infantry Battalion 300

Mariassy Jagers 200

Kaiser Dragoons - 2 sqns 300

Bussy Mtd. Jagers - 2 sqns 200

1 "Cavalry" battery

Main Column

Hadik's Division

Brigade: Piatti

- Kaiser Dragoons - 4 sqns 300

Karcy Dragoons 1100

Brigade: Bellegarde

- Jellacic I.R. 600

Archduke Franz Anton I.R. 860

Brigade: St. Julien

- Wallis I.R. - 3 bns 2200

Kaim's Division

Brigade: de Briey

- Kinsky I.R. - 2 bns 1600

Brigade: Knesevich

- G.D. Tuscany I.R. - 3 bns 2190

Brigade: Lamarseille

- Archduke Joseph I.R. 3 bns 2100

Zach's Grenadier Division

1st Brigade

- 5 Grenadier Battalions 2110

2nd Brigade

- 6 Grenadier Battalions 2240

Morzin's Division

Brigade: Nobili

- Archduke John Dragoons 860

Liechtenstein Dragoons 1000

Left Column: F.M. Ott

Advanced Guard: Gottesheim

- 1 Coy Jagers 40

Lobkowitz Dragoons - 2 coys 250

Frolich I.R. - 1 bn. 500

1 “Cavalry” Battery

Division: Schellenberg

Brigade Retz

- Frolich I.R. - 2 bns 1050

Mittrowsky I.R. - 1 bn 850

Brigade: Sticher

- Lobkowitz Dragoons - 4 sqns 490

Spleny I.R. 1 bn 700

Colleredo I.R. 2 bns 1400

Division: Vogelsang

Brigade: Ulm

- Stuart I.R. 1280

Hohenlohe I.R. 220

Right Column: F.M. O’Reilly

- 1 Coy Jagers 40

Mauendorf Hussars 3 1/2 Squadrons 430

5th Hussars - 2 sqns 230

4th Banat Grenzer Regiment - 1 bn 530

1st Warasinder Grenzer Regiment - 1 bn 760

Ougliner Grenzer Regt. - 1 bn 600

Ottochaner Grenzer Regt. - 1 bn 300

Wurttemburg Dragoons - 1 sqn 110

1 “Cavalry” battery

The Austrain Army at Marengo had between 90 and 100 guns, those listed above are included in that total. Both the main colum and the left column possed an Artillery reserve. Therefor, when allocating batteries a number should be retained for each reserve

Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #20

Back to First Empire List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1995 by First Empire.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com