Letters on: That flag and thanks Tino...; Sharpe comment; From the horse's mouth; More battles please..; Rip Off & Swindle; Russian Ranks and Jäger Organisations...; The Lost Eagles of the 4ème de Ligne; Saint-Hilare, The Career...; Observations on German Ranks...; March Rates, that flag again...; More on the Hanseatic Legion and Women in the Napoleonic Wars; A reply to Ian Fletcher;

Letters on: That flag and thanks Tino...; Sharpe comment; From the horse's mouth; More battles please..; Rip Off & Swindle; Russian Ranks and Jäger Organisations...; The Lost Eagles of the 4ème de Ligne; Saint-Hilare, The Career...; Observations on German Ranks...; March Rates, that flag again...; More on the Hanseatic Legion and Women in the Napoleonic Wars; A reply to Ian Fletcher;

That flag and thanks Tino...

Dear Sir,

Just a quick note re issue 19, Dispatches.

John Walsh has provided several French inscription translations. The last “VAINCRE OU MOURIR” should read “TO CONQUER OR DIE”

Thanks for an excellent magazine. My personal thanks to Hans Tino Hansen for his article on the Royal Danish Norwegian Army, a long standing interest of mine.

Ashford Kent.

That Flag Again...

Dear Editor,

On page 43 (of issue 18), Stephen Ede-Borrett wrote an article on an unusual Napoleonic Flag. He asks if any of the units ever saw any action before their disbandment upon the fall of the Empire in 1814.

The engraving you’ve printed belongs to a series of 12, depicting the Gardes d’honneur of the cities of Amsterdam, Rotterdam, The Hague, Dorchecht, Leiden, Haarkem, Utrecht, Gronningen, Arnhem, (the now province of) Dienthe and Delft. The city of Amsterdam had 2 Honour Guards, one naval as published and one consisting of Cavalry and Infantry. Only the engraving of the Amsterdam Naval Gardes d'Honneur shows a flag.

These Gardes d’Honneur were only raised to accompany Napoleon on his visit to Holland in 1811. Later in 1813, Napoleon raised Gardes d'Honneur with the sons of fine families, - held “hostage”.

The 1811 Gardes d’Honneur were never meant to have any real military purpose whatsoever.

The series called “Uniformes des Gardes d’Honneur des différens Corps dans les sept Départments de la Hollande formés pour la reception de sa majesté l’Empereur et Roi”, was published by I. Maaskamp, Amsterdam, 1811.

They were reprinted in 1904 by Sabretache, numbered edition (Paris) and again in Paris in 1984 in a numbered series of 500 copies. I have in my collection two originals, Leiden and the Amsterdam Naval Guard of Honour, and the latest reprint of the series.

I would like to help Mike Siggins (page 36) with some names.

D.H. Chasse: David Hendrik(us) Chassé

Note: Hendrick is the shortened version of Hendrikus, just as Harry is to Harold. born Tiel (The Netherlands) 10.3.1765, died 2.5.1849

H.G. Perponcher. Hendrick Georg Baron de Perponcher-Sedlnitinky born The Hague 19.5.1771 died Dresden 19.11.1856.

J.A.C. Bartles

Wassenaar, The Netherlands

Sharpe comment...

Dear Sirs,

It is with interest that I read the letters in FE18 & 19 regard-ing Central Television’s “Sharpe” series. Without a doubt this drama is excellent, but I do agree that there is something lack-ing. As Stuart Hardy pointed out, a number of the best characters appear once and then vanish. Some are killed off, despite having significant roles in later novels in the series, whilst others like Major Hogan (played by the superb Brian Cox in the first series) simply disappear. What happened to Robert Knowles, Captain Leroy, etc? Also why did the programme-makers choose to ignore the “Gold” and “Sword” novels?

I share Stuart Hardy’s view that Central Television are rushing things. There is the potential for each book to be developed into a full length series. (The BBC managed this quite well with Michael Dobbs’ political thriller “To Play the King”, the sequel to “House of Lords”. I am sure Central Television could do the same.) It must be said that whatever form it takes, the “Sharpe” series will always be a welcome change from the usual offerings.

There is another issue which readers might like to consider. Whilst it is relatively easy to get the historical facts on all aspects of the Napoleonic era, there appears to be an appalling lack of information about the opportunities this presents, e.g. wargaming, reenactment etc. To some, it must appear that people who participate in such activities are like a little ‘clique’, whose ranks are closed to all others. Surely we should try to dispel this image. I have no doubt more people would get involved if they simply knew where to begin. The possibilities which are there are being lost on many people.

When I say I am a Napoleonic Enthusiast, vacant expressions and comments like “Oh, that’s nice”, are a common response. (Is it because I'm young or because I’m female?) Surely we should try to make people aware of the options open to them? It is only by chance that I discovered this magazine. How many other people are still looking?

Doubtless, events like the First Empire show help to promote bodies like the Napoleonic Association, but as such events tend to be concentrated in the Midlands and the South of England, they are of little benefit to those who live elsewhere. Pity help any enthusiast from Shetland! I do appreciate that the costs of mounting such a show can be prohibitive, but nor is it an easy matter for enthusiasts from any distance to travel, especially if you’re a student relying on public transport. I do not live in a remote area, but can fully understand the difficulties faced by anyone who does.

What is needed is a far greater flow of information, so that people are made aware of what’s available. Just how we go about supplying this better information is another matter, and one which I would be interested to hear other readers opinions of.

Hilary Greer

Cumbernauld, Glasgow.

And from the horse’s mouth...

Dear Dave,

In answer to your letters and those of others (concerning ‘Sharpe’ I offer the following reply:

We make ‘Sharpe’ for an audience of 10 million viewers of which a very small number are enthusiasts of the period - we have to bear in mind that we need to offer the full flavour of the period but tempered with modern ability to understand - for example - the oft-heard shout in the war “Turn out for biscuit!” is regarded as a prelude to seeing a commissary dispensing Digestives!

Of all the questions I've had, the one rarest is “What is it like out there?” The answer is that you need as a military adviser - tact, excellent communication skills, hard-bargaining ability, peak physical fitness; and be able to adapt/ improvise/ overcome; be able to interpret and compromise - and have a complete and utter knowledge of practical/ theoretical/ hypothetical situations 1810-1814; a bag full of tools, lots of gunpowder and flints; endless patience and an edged weapon; a sense of humour and plenty of loose change.

A knowledge of military history helps too...

Sharpe on location, The Crimea

More battles please...

Dear Mr. Watkins

Having recently received my copy of First Empire (issue 19) I am writing to say how much I enjoyed reading Major Field’s article on the Battle of Craonne. It is for this kind of scenario article that I subscribe to your magazine and feel there have been too few such articles within its pages so far.

Therefore I would make a pleas form more such items particularly on less well known battles. For example Montmirail, mentions in the above account, is an action I have been keen to refight as a wargame for some time but have been unable to find enough information.

On a similar note, in reading Geert van Uythoven’s article on the Dutch Army, I read with great interest an account of engagements between Dutch and French forces against Swedish troops in 1807. Having an interest in the Swedish Army of the Napoleonic Wars, I am eager to find out more about these rare battles and would ask if a further article could be forthcoming specifically on these actions.

Peter Clayton,

Tattenhall, Cheshire

Editor: See my reply to the following letter with regard to magazine content, as for the Franco-Dutch v. Swedes, Geert is currently digging out all the info on the Actions of the Dutch Army and the Swedes will no doubt surface in that.

Yet more battles please...

Dear Sir,

My fellows and I have read your magazine from the very first issue and being primarily Napoleonic Wargamers, we were overjoyed to have a magazine all of our own. We have used many of your battle descriptions for refights and on the whole they work well.

Recently though your magazine has been drifting away from this aspect and has been overwhelmed with boring and petty details. So would you please include more battles, campaigns and army lists and have less about how many buttons the Hanseatic Legion had on their underpants.

A loyal but frustrated reader.

Edinburgh, Scotland.

Editor: For a minute I thought you had a point so I dug out the last 6 issues and found that issue 19, had 1 battle 1814 - France, issue 18 covered 2 in 1812 - Russia, Issue 17 had 2 Peninsular and 1 theoretical, issue 16 had 2, 1 Italy 1814, 1 Peninsular, issue 15 had none - but did have a scenario and a refight of a scenario, and issue 14 had 1, Rolica, and the con-clusion of the Anglo-Russian Invasion in Holland. And prior to that all the way back to issue 1, I have tried to ensure that we have at least one battle article in each issue and preferably two, but it isn't always possible, but we will continue to do so.

What I have tried to do over the last few years is steer First Empire away from specific Wargaming articles - having said that there a quite a few lined up for next year - and provide informa-tion that you can extract and use for whatever purpose you desire. For example my perception of how Napoleonic battles were fought has been changed radically by the articles that have appeared since issue 15. Now I want my wargames to be as true a reflection as possible of the real thing, you can’t do that with people always spoon-feeding you rule mechanisms and painting guides, you need to know the basis on which such mechanisms can be based.

With regard to the Hanseatic Legion article, not only did this give you a uniform guide, but part 1 also gave you the reasons for its formation, what it did, who commanded it and a feel for the campaign of 1813. Don’t you want that information as a war-gamer? Of course it may not be relevant for you particular inter-est, but it may spark or rekindle interest in that area.

Rip Off & Swindle...

Dear Sir,

Having read your tail-piece in the October/November issue of First Empire concerning the ludicrous prices charged by some of the organisers of Wargaming and Modelling shows, I have decided to put pen to paper in your support.

As the manufacturer of 25mm Hinchliffe figures and equipments, I frequently meet the problem of exorbitant costs that you de-scribe, and many fellow traders in the hobby have the uncomfort-able feeling that they are being “Ripped Off” by the entrepre-neurs who are the organisers behind the scenes.

Not content therefore with doing nothing to straighten matters out, I organised my own show this year at Thornton Dale. I asked the best demonstrators of wargaming to put on a show worth look-ing at, and I invited 9 traders, covering all the main facets of the hobby, to come and sell their wares, thus ensuring that a very high standard of gaming took place, and the right mix of merchandise was available to the purchaser.

The resulting show was deemed to be a great success, both by the customers who were charged £1.50 entrance fee (accompanied children free), and by the traders who only paid £10.00 each for a stand. As the organiser, I was satisfied with both the number of customers through the door, and the sales that the show produced, and it will be repeated next year probably at a larger hall, but at no extra cost to those attending.

Many of the existing shows around the country are very well run nd offer a fair service at a fair price. Others, however, are now approaching the “Rip-Off and Swindle” stage, and these are giving the hobby a bad name. Since there are now approximately 67 shows taking place each year, and show saturation is now approaching, there is every chance that the badly run ones will go into a downwards death spiral and disappear in a cloud of plastic games and fantasy figures.

Ian Campbell

Ellerburn Armies,

Thornton Dale, N. Yorks.

Editor: There you go, point proven. I rest my case and grin....

Russian Ranks and Jäger Organisations...

Dear Sir,

Please allow me to supply some additional information for the benefit of Mr. Solimine and others who are so interested.

The following table show the Infantry ranks as given by Zweguint-zow (in USGS form) and their equivalent anglophonic names are listed below. Field officers, majors and above, rode as was normal European practice.

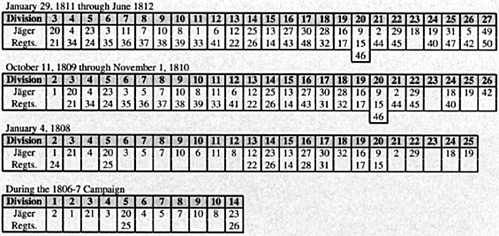

Zweguintzow gives the following distribution of Jäger Regiments at the listed dates. Presumably the reorganisations took place on the first dates and stayed unchanged until the next reorganisa-tion sometime after the second date. The 49th and 50th Regiments were raised on November 23, 1881, the 47th and 48th January 29, 1811, and the 33rd to 46th Regiments on November 1, 1810.

Jonathan Gingerlich

Santa Monica. CA, USA

The Lost Eagles of the 4ème de Ligne

Dear Sirs,

In a rival magazine, Wargames Illustrated, number 72 of September 1993 an article by Stephen Ede-Borrett appears entitled “Battal-ions, Eagles & Flags” which states that the Fourth Ligne had two Eagles captured by the Russian Army, the first on 10th November at 1805 at Krems and the second on 2nd December at Austerlitz. Mr. Ede-Borrett does not indicate his source.

I would appreciate any assistance that you or the readers can give regarding the history of the apparently unfortunate Fourth Ligne in late 1805 with particular reference to the loss of these Eagles.

Doran. R. Henderson

Kingston, Ontario

Editor: According to Austerlitz 1805, Dr. David Chandler, Osprey Campaign series No. 2, page 72 “...the Archduke... immiediately ordered the 15 available squadrons of the (Russian) Guard Caval-ry, led by 1,000 cuirassiers, to destroy Vandamme from the flank while the (Russian) Grenadiers attacked from the front. In the nick of time the 4ème Ligne’s foremost battalion formed square on Major Bigarré’s order. But the Russian Cavalry swung aside to reveal six horse-artillery pieces trained on the square, which received a hail of death-dealing canister. Vandamme, already wounded earlier in the fray rushed the 24ème Légère to the 4ème’s rescue, but it could not make its presence felt before the cuirassiers fell upon the battered square with immense shock. Over 200 French infantry were cut down, and the 4ème’s treasued eagle-standard was captured, to be borne off in triumph to the rear.” I’m afraid I can throw no futher light on the matter as I personally have little material on this campaign, so anybody out there able to add to this?

Saint-Hilare, The Career ...

Dear Dave Watkins

Thanks for issue 19 of First Empire. Having read the Dispatches pages I thought the following may be of interest to JW Drage and the rest of your readership on the subject of the life of St. Hilaire.

Thanks for issue 19 of First Empire. Having read the Dispatches pages I thought the following may be of interest to JW Drage and the rest of your readership on the subject of the life of St. Hilaire.

SAINT-HILARE (Louis Vincent Joseph Le Blond, comte de), general, born at Ribemont (Aisne) on 4th September 1766, died at Vienna as the result of wounds, 5th June 1809. Cadet in the regiment of Conti-cavalerie as a child adopted by the regiment, 13th September 1777. Volunteer in the regiment d’Aquitaine-infanterie, 7th November 1781, and embarked for the East Indies shortly after, staying there until 1785. Made porle-drapeau 11th April 1783; promoted sous-Lieutenant in the regiment d’Aquitaine (numbered in 1791 35e d’infanterie) 16th September 1783; Lieutenant en 2c 1st June 1788; Capitaine 1st July 1792. Served in the Army of the Alps 1792-1793. Present at the siege of Toulon, and was named provisional adjudant général chef de bataillon by the representa-tives of the people with the Armies of the Dept. of Midi, Barras and Saliceti, on 27th December 1793.

With the Army of Italy serving under Masséna, and was employed in Mouret’s division on the expedition to Oneille, 5th April 1794; then under Laharpe in August 1794. Commanded the detachment that seized the “Jourdan Coupe-Têtes”, 10th November 1794. Named provisional adjudant général chef de brigade by the representatives with the armies of Italy and the Alps, Ritter, Turreau and Saliceti, 3rd December 1794. Captured the Col de Termes, 14th April 1795; confirmed in his rank by the Committee of Public Safety, 13th June 1795. Defended the post of Petite Gibraltar, 19th September; named provisional Général de Brigade by the representatives of the Army of Italy, 26th September 1795. Wounded at Loano where he lost two fingers of his left hand, while under the orders of Laharpe, 24th November 1795. Commanded the 3rd Brigade of Laharpe's Division, 24th December Departed for the waters of Digne and left the command of his brigade to Cervoni, March 1796.

Employed in Masséna’s Division 2nd July 1796; Division Augereau 6th July; Division Sauret, end of July 1796. Victorious at Gavardo, 4th August 1796, and seized the Rocca d’Anfo, 7th August. Division Vaubois, 2nd September, and served at Bassano, 8th September Then at Due Castelli he was wounded in both legs at Saint-Georges, 15th September 1796. Confirmed in his rank of Général de Brigade by the Directory Executive, 25th September 1796. Commandant at Lodi, 7th January 1797, then employed in Kilmaine’s Division left behind in Italy 11th March. Commanded at Toulon the depots of the units of the Army of the Orient and the Var department, 16th May 1798, then provisionally the 8th Military Division at Marseilles, 14th October 1799. Promoted Général de Division, 27th December 1799. Reinforced Suchet at the head of the National Guards of the Var and Bouches-du-Rhône, 15th May 1800. Commanded the 15th Military Division at Rouen, 12th November.

Commandant of the 1st Division of the Camp of St. Omer, 31st August 1803, then with the 4th Corps of Marshal Soult, 29th August 1805. Signalled the capture of the Pratzen Heights at Austerlitz where he was again wounded, 2nd December 1805. Received the Grand Eagle of the Légion d’honneur, 27th December 1805. Served at Jena, 14th October 1806, Bergfried, 3rd February 1807, Ziegelhoff, 7th February, Eylau, 8th February, and Heilsberg, 10th June. Obtained an endow-ment of 30,795 Francs in annual rent from the Grand Duchy of Varsovie, 30th June 1807. Another endowment of 5,882 francs in rent on the Grand Livre, 23rd September 1807. Then two others followed - one for 30,000 francs in rent from Westphalia and the other for 25,000 francs in rent from Hanover. Commander of the Couronne de Per 1808; commander of the 1st Division of the Army of the Rhine under Davout, 12th October 1808. Made Compte de l’Empire by patent letters 27th November 1808. Commanded the 3rd Division of the 2nd Corps under Lannes in the Army of Germany, 30th March 1809.

Served at Tengen, 19th April, Schierling, 21st April, Eckuhl, 22nd April, Ratisbon, 23rd April. Was hit by a bullet in the right leg at Essling, 22nd May 1809, and died in Vienna as a consequence of the wound at the home of Count Apponyi The name of General Saint-Hiliare is inscribed on the southern face of the Arc du Triomphe de l’Etoile.

(Loosely translated from Volume 2 of Dictionnaire Biographie des Généraux & Amiraux Français de la Révolvution et de l'Empire Georges Six, Paris 1934. This is the most comprehensive work I know of on French officers of the period.)

I hope the above is of some help!

John Shelley

Tokyo, Japan

Editor: Thanks are also due to Dr. David Chandler, who took the trouble to respond to this querry by providing the same information in the original French and also the illustration used. David is recovering from a serious illness, so the effort taken is appreciated. Get Well soon David, from all at First Empire.

Observations on German Ranks...

Dear David,

The orthography of German officer titles having stimulated considerable discussion among your readers, I thought the following observations might be of interest.

First, it is important to keep in mind that there was no single system of ranks for officers or other ranks in Germany during the Napoleonic period. Although the logic of a simple progression from lieutenant to general enforced much commonality, the welter of states, large and small, that made up what we now think of as Germany followed no uniform rank structure. We thus find the tiny Principality of Waldeck using the tide ‘Gross-major’ for its infantry battalion commander and Württemberg using the Austrian rank ‘Feldzeugmeister’ for its most senior generals.

Even leaving aside the unique Austrian usages, it can thus be somewhat mis-leading (albeit convenient) to talk of a single set of ‘German’ ranks in the Napoleonic era.

Second, there is the problem of Gallic intrusions into what otherwise seem very Germanic tides. The prevalence of French influence (cultural and linguistic as well as military) meant that many rank tides as well as other military terms of art (‘debouchieren’ or ‘deployieren’ for example) were borrowed directly from the French: hence ‘Oberst - lieutenant’, and ‘Capitaine’, ‘Capitan’, or ‘Kapitän’. This begins to change slowly in the latter years of the period and, as other readers have noted, picks up speed as the 19th century progresses. Soon it became a matter of nationalistic pride to use only ‘truly Germanic’ seem-ing tides for all soldiers, so that Austro-Prussian General Valentini, in the preface to the second edition of his history of the 1809 campaign (1818), had to excuse himself for continuing to use some French military terms.

Third, it is important to note that the German language did not achieve a uniform system of orthography until after the estab-lishment of the Prussian Empire in the 1870s. As a result, what appear to us now as ‘variant’ spellings and usages were common up through the Franco-Prussian War. The initial letters ‘c’ and ‘k’, for example, were nearly interchangeable in Napoleon‘s day and one often finds ‘p’ standing in for ‘b’. Little wonder that there is so much variety in German spellings of ranks. This lack of uniformity may also have enhanced the attractiveness of the rather more standardised French language.

All of these complications are compounded by information that comes to us from French sources (where it has often been trans-lated from German into French) and by the differences between cavalry and infantry ranks. The most notable of the latter being the use of ‘Rittmeister’ for cavalry captains in many monarchies.Finally, it is worth noting here that ‘Oberst’ and ‘Obrist’ were used interchangeably during the Napoleonic period: the latter being merely an archaic version of the former. ‘Oberst’, by the way, is derived from ‘Oberster’ meaning ‘uppermost’ or ‘highest’.

In researching German armies of the Napoleonic era, therefore, one must be prepared to cope with a profusion of ranks and some dramatic variations in spelling and usage. Although there is thus no single ‘system’ of ranks, with some imagination and the help of tables such as that provided by Mr. Cook, the reader will quickly develop a general understanding of officers’ positions and functions.

I would also like to comment on Marshal Augereau’s career, spe-cifically his activities in 1809. Although Napoleon intended to place the old marshal at the head of VIII Corps for the war with Austria (Correspondence, 15029, 8 April 1809), there is no evi-dence to indicate that Augereau ever went to Germany that year. The cows never attained its intended organisation (leaving the Württemberg contingent as the de facto VIII Corns). Nor did the Duc de Castiglione command the French reserve forces in Germany; these (the ‘corps d’observation de l’Elbe’) were under Kellermann and later Junot. Napoleon did designate a new VIII Corps in August 1809, but this formation, located in central Germany (Bayreuth-Dresden), was likewise commanded by Junot. Augereau appears in Catalonia in the fall of 1809 as commander of VII Corps, but his activities in the earlier part of the year remain a small mystery; perhaps he was still recovering from miseries and wounds of the 1807 campaign. As Elting points out in Napole-on’s Marshals, Augereau has never had a proper biographer; his life is one of the many aspects of the era open for new research.

Jack Gill

Alexandria, Virginia, U.S.A.

March Rates, that flag again...

Dear Sir,

The article on Napoleonic March Rates requires some comment. The Prussian step was 28" (German) which was nearly 29" (imperial). (Source: Duffy: The Army of Frederick the Great, David & Charles, Newton Abbott, 1974) The French pace was 2' in length which is approximately 26 Imperial inches, however, this measurement antedated the metric system.

Permit me to offer an alternative translation of the flag in-scription.

(the reader may substitute “Conquer or Die!” for the last phrase)

Now we come to the matter of censorship. Certainly, readers’ letters should not indulge in the argumentum ad hominem, or for the non-classicists: personal attacks. But, they should also be able to query or correct statements made in articles and letters, provided that they do so in a civilised manner. Now, I realise that some of my utterances may seem a little acerbic, but it is very difficult to convey the rictus sardonicus which accompanies what is written. At this point let me express my complete agreement with the remarks in Ian Fletcher’s letter. Yet, it must be admitted that Peter Hofschröer is by no means the only offender. It is perhaps fortunate that some of the people, whose books are criticised in the letters’ column do not read this journal; otherwise the subjects of ‘Reader‘s Reviews’ might produce some rare beauties. Perhaps, it might be advisable to expurgate or not publish the more outrageous reviews. This policy must be seen to apply across the board, otherwise it will be pointless. To finish, it might be apposite to cite an example of both a letter and a review. Hans Tino Hansen’s letter on the qualities (or lack of them) of the Hanseatic Legion is a good example of a letter. And the Editor at least gives a book a fair trial (before he hangs it).

To end, if you put 20 Napoleonic enthusiasts in a room and asked them to name the leading English-speaking writers on Napoleonic themes, you would get at least 30 different answers. Here is a provisional list which is subject to amendment: Chandler, Elting, Horward, and Rothenberg; this deals with the doyens in this field. Duffy’s Napoleonic books are not his best, but that is more a comment on his Eighteenth century and World War II books, which are excellent. To this we must add Griffith (tactics), Haythornthwaite (uniforms), Bowden, Nafziger (orbat studies), Gill (Rheinbund), Alexander and Esdaile (Napoleonic Spain), one is tempted to add Hamilton Williams to this list, but that might stir up the hornet’s nest.

Magnus Guild

Edinburgh, Scotland

More on the Hanseatic Legion and Women in the Napoleonic Wars.

Dear Dave,

Unfortunately you did not use the revised version for the article on Hanseatic uniforms, so I’ll have to add the following amendments:

The Hanseatic Bürgergarde in exile originally continued to wear the spring 1813 uniform, the British ones probably were not issued before the siege of Hamburg.

The list of sources also includes: Gaedechens, C.F.: Hamburgs Bürgerbewaffnung. Ein geschichtlicher Rückblick. Hamburg 1872.

The illustration on p.4 is from the title page of: Gedenkbuch des Jubelfestes am 18.März 1813 zu Hamburg, wie es vom Hanseatischen Vereine und seinen Waffengefährten begangen worden. Hamburg 1838.

A few words in response to Hans Tino Hansen’s letter in First Empire #19. Of course the quality of the Hanseatic troops is difficult to assess, as they only fought in a few, mostly minor and fairly obscure actions. I was aware that Danish sources tend to have a low opinion of them, but then contemporary Hanseatic sources aren’t always very complimentary about the Danish troops either (for instance, the Danish Jager involved in the fight on the Veddel on May 12th, 1813 were accused of being the first to break and run, and of retreating in worse disorder than even the Bürgergarde present, while the Mecklenburg Guard Battalion seems to have been universally praised for its conduct). As Mr. Hansen rightly points out, judging the quality of troops was to a large extent subjective. Knowing this, I took forexample, Boye’s more enthusiastic statements with a pinch of salt.

That aside, I did not intend to imply that the Hanseatic Legion was appreciably better than the other German volunteer formations hastily raised in the spring of 1813. Indeed, I mentioned some factors that obviously must have lowered their worth on the field - the tradition of avoiding military service, the lack of experi-enced home-grown officers and NCOs, the peculiar republican resistance to military discipline and the more abrasive type of professional soldiers (some of these problems must sound very familiar to cognoscenti of the US volunteer forces in the 19th century). Especially when it came to foraging, discipline could have been better (a problem hardly unique to the Legion), but on the other hand desertion does not seem to have been a problem (except for a few of the foreign Legionnaires). I thought it unnecessary to explicitly ask readers not to expect miracles from troops who were organised from scratch, put into the field and badly led into major actions within less than two months of the first call to arms. Let’s be fair - even the troops who fought at the First Bull Run must have been better trained than they were! (Need I remind anyone that the Prussian Landwehr was organised, raised and trained - on an existing military infrastructure - since February 1813, but few if any of its units saw action before August?) I would not have dreamed of comparing Hanseatic to the King’s German Legion! At least the Hanseatic Legion seems to have overcome a lot of its handicaps through its high and resilient morale. You would have expected the Danish troops (regulars of long standing) to have done better against the Hanseatic and Hanoverian volunteer formations than they in fact did. The 17th Polish Lancers contained quite a few veterans, but after the Russian campaign they were under strength (the three squadrons also included the remnants of the 9th and 19th - the 17th and 19th had only been raised in Lithuania in the summer of 1812) and presumably badly mounted, at least in the spring. The Hanseatic troopers do not seem to have been overawed by them: On or about April 30th 1813, 40 Lübeck cavalry (with 20 infantrymen in support) led by sergeant-major Lipschay ambushed a detachment of the 17th (two squadrons according to Gaedechens, which may be an exaggeration) near Winsen, killing an officer and capturing six wagons.

By the way, it may be of interest to some that at the time the troops of the Legion were not called “Legionäre” (Legionnaires), but “Legionisten” (singular “Legionist”) or “Hanseaten” (singu-lar: “Hanseat”).

Further to Terri Julians’ “Women in the Napoleonic Wars” I’d like to mention that the era also saw quite a few women fighting either as guerrilla fighters or in the ranks, the latter usually disguising themselves as men (medical examinations then being what they were, that apparently was not too difficult). To mention examples from the Wars of Liberation in Northern Germany, there was Eleonore Prochaska (born Potsdam 1785) who served in the Lützow infantry as private August Renz and whose sex was not discovered until she was mortally wounded at the Göhrde (16 Sept. 1813). Inspired by her example, 17-year-old Anna Lühring of Bremen ran away from home and joined the Lützowers in February 1814 under the name Eduard Kruse. She was soon unmasked (her angry father wrote to her captain), but allowed to serve until the end of the war (under the provision that two morally reliable comrades slept on either side of her at night). During the cam-paign of 1815 Ilse Dorothea Hernbostel from Achenburg in Hanover winkled her way into the Bremen field battalion where she was only found out on the return march in 1816 - after which she got too friendly with a corporal who impregnated her. Perhaps the most astonishing case - because unlike the first three, it did not involve an enthusiastic unmarried girls - it is that of Luise Grafemus, a mother of two. She went to war with her husband in 1813 and 1814, rose to become a Wachtmeister (sergeant- major) in the East Prussian Landwehr Cavalry in spite of being found out and was decorated with the Iron Cross. She returned from the war to her children a widow (her husband was killed in France on 30th March 1814), but was less well remembered than Eleonore Prochaska (who also profited from the number of writers in the Lützow Free Corps who would write poems in her honour) presumably because she was Jewish (she was born Esther Manuel in Hanau, 1785) and did not die a romantic death. Not actually fighting herself, but also acting at great risk was Johanna Stegen, who carried cartridges in her apron from an unguarded French ammunition caisson to the men of the Pomeranian Fusilier Battalion through the lines of battle in Lüneburg on 2nd April 1813.

Keep up the good work,

Aachen-Orsbach, Germany

Ninety-seven years ago, American soldier and historian Major-General Jacob D Cox wrote a book about the Battle of Franklin, fought in Tennessee during the latter part of the American Civil War, in which he took part as a Divisional Commander in the Union army. In his book, which is now regarded as a classic of its kind, he expressed the view that the role of a historian was thus, “to reach the truth by running down and fixing the facts which are omitted, and constructing an authentic narrative based upon everything which is satisfactorily and affirmatively estab-lished”.

In the last three or four years, at least four new books on Waterloo have appeared, two of which to my certain knowledge add absolutely nothing whatever to the subject and a third, the only one to offer any degree of originality, is controversial but, unfortunately, produces very little evidence to support its analysis, which reduces it to little more than a matter of opin-ion. When authors produce books that do little more than repeat what has already been said by numerous secondary and tertiary sources, warts and all, providing neither references nor a bibli-ography and are demonstrably incorrect, then surely it is right to say so.

I am neither professional writer nor trained historian but, writing from the perspective of a professional analyst I certain-ly do recognise the shallow research and unsupported interpreta-tion that Peter Hofschroer alludes to. I would certainly agree that there are many popular British writers who specialise in the Napoleonic period, but who are patently neither experts nor historians, replacing fact and reasoned judgments with generali-sations and vague analysis. I suggest a comparison of their techniques with the depth of research and informed assessment evident in David Ascoli’s exceptional treatment of Mars la Tour in his ‘Day of Battle’, for an example of the modern historian’s craft at its best.

This is also in stark contrast to the quality and quantity of work originating now in the United States on the subject of the American Civil War. I simply do not see a school of modern British military historians writing with the same authority, reliability and detail on Salamanca, on Talavera, on Vimeiro and, indeed, on Waterloo, as has Wiley Sword on Shiloh, as has Peter Cozzens on Chickamauga, as has James McDonough on Stones River, the list is endless in comparison. Where too is the modern account of Wellington’s Peninsular Army to rival Thomas Connel-ly’s history of The Army of Tennessee. Frankly, my Dear, it doesn’t exist (acknowledgements to Clark Gable).

I can understand Ian Fletcher’s irritation with Peter Hofschro-er’s style, which sometimes does his cause no good, but I find it very hard to accept Ian’s apparent argument, which I think it is reasonable to infer, that lack of “an in-depth working knowledge” of a particular language is no impediment to research using material written in that language. I am curious to know how an individual actually makes use of documentary evidence he cannot read. To follow this logic, presumably it would be reasonable to argue that someone who lacks, say, an “in-depth” or, indeed, even a “working knowledge” of the process involved in splitting the atom, is qualified to write on the subject of nuclear fission? I don’t think so. Why then, is it acceptable in the case of Na-poleonic military history, for individuals who are not competent to do so, to write professionally about certain aspects of it which they cannot possibly understand properly?

The logic of Ian’s argument, where he seems on one hand to accept that Peter is, “an authority on German military history”, whilst on the other, he does not seem to accept that he is qualified to criticise, “British historians who touch upon German subjects without an adequate knowledge of the language”, when they are wrong, escapes me entirely. Ian’s objection seems to be, not that Peter was necessarily wrong, but that it is apparently unacceptable to point out errors when the occur. Clearly it is not reasonable to expect infallibility but I cannot believe Ian really thinks it’s alright for professional writers of military history to make repeated unforced errors of basic fact. If he does, which it has to be said, is the apparent implication of his letter, then his position is simply untenable.

Peter was indeed pointing out the obvious, albeit in his distinc-tively tactless style, that a significant proportion of English speaking writers who write professionally on Napoleonic military history are actually technically untrained monoglots, unable to exploit foreign sources and, therefore, in failing to interpret, in both the linguistic and analytical sense, all the information available to them, draw flawed conclusions and, furthermore, sometimes do not even set out the facts correctly. They fail to “reach the truth by running down and fixing the facts” and, as a result, construct narratives which are neither “authentic” nor “based upon everything which is satisfactorily and affirmatively established”.

As for literary talent, this is an entirely subjective judgment. In the end one either has it or not, like what I have got (ac-knowledgements to Morecambe and Wise for those English readers old enough to remember!).

Huntingdon, Cambridgshire

Editor: In view of the debate that appears to be arising I feel here I should make some comment. Some readers appear to have a difficulty diferentiating between readers reviews and letters, and while John expresses some of my opinions in the above, I am taking this opportunity to expand on it just a little more. Both Reader’s Reviews and Dispatches are open forums, anyone can write and will usually be published. The difference between the two is as follows; if Joe Bloggs writes a letter to Dispatches and someone else subsequently writes in and calls him an amateurish idiot - it won’t get published, conversely had Joe written a book and someone having paid good money for it discovers it to be a load of rubbish, then that person is allowed to state that the book is amateurish rubbish. I don’t think we have had a Reader’s Review that goes that far yet, but I think I’ve made the point.

Early in this issue of Dispatches, the point was made that if the authors of these books that get slated read First Empire we would get some interesting letters in. Well actually they do, and/or so do the publishers. Most take an adult view of the matter, others after some initial protests when they have calmed down have admitted that fair critiscm was given or that a ‘paying customer’ has right to complain and have an opinion. One man’s meat is another man’s poison after all!

Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #20

Back to First Empire List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1995 by First Empire.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com