Run They Would Not

The Gurkha Wars of 1814-1816

by Colin Allen, U. K.

| |

The Gurkhas have long been famed for providing some of the British army's most loyal and ferocious fighting men. They have amply demonstrated these qualities during the Indian Mutiny, the two World Wars and, more recently, in the Falklands as well as in many other conflicts along the way. However, this has not always been the case; the Gurkhas were once bitter enemies of the British but, even then, succeeded in winning their respect as demonstrated by the comments of Ensign John Shipp of the 87th Foot:

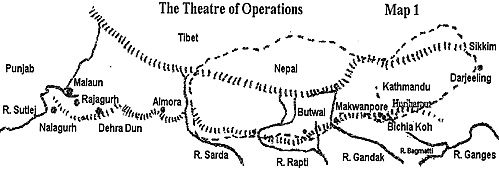

In the final years of the 18th century and the earliest years of the 19th century Nepal embarked on an aggressive policy which saw it conquer Sikkim, Darjeeling, Garhwal, Kumaon and parts of Tibet. During this period, the British were waging an increasingly difficult campaign against the Mahratta Confederacy, including repeated failures to capture the fortress of Bhurtpore. When the Nepalese state came into contact with the British controlled part of India, the Nepalese began an insidious invasion, occupying one village at a time until, by 1814, the borders of the state had been pushed so far that conflict with the British forces was seeming more and more likely. The Nepalese Prime Minister, Bhim Sem, saw the series of British reverses as evidence of weakness and declared that an army which had failed to take the fortress would be unable to penetrate the natural fortress formed by the Himalayan foothills. However, there was some dissent within the Nepalese command; their leading general, Amarsing Thapa, took a far more realistic view of the British military's ability when he said:

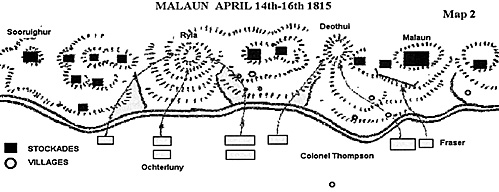

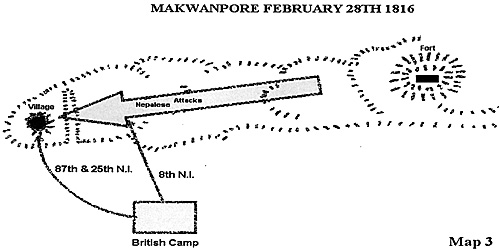

However, he was unable to sway the government in favour of taking a more conciliatory course of action, partly due to the fact that much of the revenue from the newly acquired villages was going to line the pockets of the members.  THE CAMPAIGN OF 1814-15The final step on the road to war was taken in May 1814 when Gurkha soldiers raided three British controlled villages in Butwal district, killing 18 policemen and torturing a village headman to death. The British Governor General sent Bhim Sem an ultimatum which was contemptuously rejected, whereupon the British laid plans to attack the Gurkha territory. The offensive was to be carried out by four columns under Major General Marley, who was to attack from Dinapore towards the Nepalese capital, Kathmandu, with 8000 Indian troops and the 24th Foot, Major General J.S. Wood, who was to attack from Butwal towards Palpa with 3000 Indian troops and the 17th Foot; General Gillespie, who was to attack the Doon valley and Srinagar with 2500 Indian troops, the 1/53rd Foot, a force of dismounted dragoons and a few guns and, finally, General Ochterlony, "Ould Maloney" to the Irish troops or "Loniata" to the Indians, who was to take his force of 6000 Indian troops and 12 guns along the left bank of the Sutlej Riverto attack the main Nepalese army under Amarsing Thapa at Malaun. The plan was for Ochterlony and Gillespie to move out first, cut the Nepalese supply lines and engage the enemy, after which Wood and Marley would, hopefully, be able to carry out unopposed marches into the Nepalese hinterland. Against this force, the Nepalese could amass some 12000 poorly equipped but mobile and courageous men to cover the enormous frontier and, although the mountains gave them great defensive advantages, they also made supply and movement incredibly difficult, it being a two month march from Kathmandu to the border over almost impassable tracks. Nevertheless, the Gurkhas were determined to defend every inch of their territory rather than falling back and forcing the British to attack through such appalling terrain. A formal declaration of war was issued in Lucknow on November 1st but the British columns had already been set in motion, at least for a little while. Marley's ColumnMarley moved up to the border and was promptly attacked by relatively small enemy forces which overwhelmed two advanced parties at Persa and Summunpur. His confidence completely shaken, he pulled his forces back and promptly rode off back home without telling a soul, to be replaced by Major General George Wood. His opponent, Bhagat Singh, however, had been overcome by his own temerity and refused to attack the unhappy British, claiming that he was outnumbered ten to one. Recalled to Kathmandu, Bhim Sem showed what he thought of him by ordering him to open a Durbar while dressed in petticoats. Wood's ColumnThe column under Major General J.S. Wood, proceeding through heavy jungle, also met with problems when the advanced guard, consisting of men of the light company of the 17th Foot mounted on elephants, was ambushed as it was about to leave the trees and the startled animals stampeded back through the main body, which was thrown into confusion, made worse by many of the Nepalese being uniformed in red. However, Captain Croker's company of the 17th Foot managed to outflank the enemy position and chased them back up a wooded spur towards a new position in the hills above Butwal. On inspection, Wood decided that the new position was too strong for his force to take and ordered a retreat which was to be covered by the embarrassed light company. Gillespie's ColumnGillespie's offensive suffered from the major disadvantage of being led by a man known as "the bravest man who ever wore red". Gillespie definitely rivalled Ney for the title of the rashest commander of his age, but was also a drunkard and a sadist. Unsurprisingly, he was not overly popular with his men! He sent Colonel Sebright Mawbey with 1000 men to capture the fort at Kalunga (now Nalapini), which was held by Amarsing's nephew, Balbahadur, with 600 men of the Purana Gorakh Regiment, the elite troops of the Nepalese army. On arriving before the position Mawbey rightly decided that his force had no chance of taking it and sent a message to Gillespie asking for more men and some artillery. Unfortunately for the British, Gillespie decided to send something else as well... himself! Arriving in front of the position at the end of October and having had an ultimatum torn up by Balbahadur, he decided to attack from four different directions at noon on the 29th. Three columns, under Captain Fast from the northwest, Major Kelly from the north and Captain Campbell from the east would distract the defenders while the main attack was made from the south by Major Carpenter, accompanied by his general; each attack was to be led by a company of the 53rd Foot. In order to coordinate the attacks in the mountainous terrain, the artillery with the main body was to fire a salvo at exactly 10 o'clock as a signal to be in position in two hours time. Ten guns were transported by elephants to a small plateau which overlooked the fort and a bombardment was commenced at dawn, with virtually no effect at all. On seeing the cannonballs literally bouncing off the small fort, Gillespie appears to have had an attack of insanity and suddenly ordered that the attack would take place at 8am instead, despite the fact that none of the minor columns could be in position by then. However, the signal salvo was fired and, of course, totally ignored by the other columns who assumed that it was part of the bombardment. Undaunted, Gillespie ordered his men forward and the attackers, led by the company of the 53rd Foot, who were burdened with heavy scaling ladders, were met by a storm of fire from the fort, which set fire to the dry grass around the base of the walls. This was too much for the British and Indian troops who fled back down the hill on which the fort was situated. As Gillespie reorganised his battered force the bombardment continued, evidently with some effect as a Gurkha suddenly appeared through the smoke, waving his hands in the air. Thinking that he had come to discuss terms the British ceased firing and went out to meet him, only to discover that he had been injured in the jaw and had come to be treated by the British doctors; having received treatment he then requested permission to return to his colleagues! Three more companies of the 53rd Foot, who had arrived the previous night after an exhausting march, were now ordered into action to attack a small gate in the northwestern wall of the fort, after it had been demolished by two guns of the Bengal Horse Artillery, who had also just arrived. However, due to their condition, the men were slow in coming into action and Gillespie ordered the small force of 60 dismounted troopers of the 4th (Royal Irish) Dragoon Guards to charge the still intact gate. The assault was met by a hail of musketry and Gillespie finally paid the price of his own rashness, being mortally wounded and dying in the arms of Lieutenant Frederick Young. The attackers turned tail and fled, much to the consternation of the flanking columns who now emerged from the forest around the fort to see their comrades in rout, the dead Gillespie being carried away and the Nepalese gleefully disabling the guns! Colonel Mawbey of the 53rd now assumed command and ordered a withdrawal, the British having lost 4 officers and 29 men killed as well as 15 officers and 213 men wounded. Heavy artillery was sent for from Delhi and, when they finally arrived, a more effective bombardment was carried out. By November 27th a practicable breach had been made and an assault was planned for the following day, to be carried out by the flank companies and one battalion company of the 53rd and the grenadier companies of the Indian units, the whole being under the command of a Major Ingleby. The assault was a complete failure, only Lieutenant Harrison and a few men of the 53rd reaching the breach. The assault was called off with a loss of 4 officers, 15 British infantry and 18 Indians killed, as well as 7 officers, 215 British infantry and 221 Indians wounded. There were some claims that the 53rd had refused to press their attack properly and a number of duels were later fought by officers of the 53rd in defence of their honour. Following this debacle, Mawbey decided to blockade the fort but, on December 1st 1814, Balbahadur cut his way through the besiegers with his remaining 70 men and disappeared. Inside the fort, the British found 520 dead and wounded, some of them women and children; their own losses throughout the assaults and siege totalled 31 officers and 750 men. Mawbey was probably relieved to see Major General Martindell arrive to take over the command as Runjoor Singh had now arrived in the area with a small force. Martindell forced him back to Jytuk, although the Nepalese launched harassing attacks at every opportunity, and the two forces remained there, glaring at each other. Ochterlony's ColumnOchterlony was a very different character to Gillespie; bold when it was required but also appreciating the need for caution when the situation demanded, as he believed it now did. The first position that he came up against was the small fortress of Nalagur and its satellite fortlet at Taraghur, positioned on the first ridge of the Himalayan foothills and rising above bamboo forests and thick scrub. Ochterlony resolved to take this position and sent a force under Colonel Thompson, consisting of the 3rd Native Infantry and assorted light companies, to cut off the fortlet from its parent. After an arduous struggle, several guns were positioned overlooking the main fort and a bombardment was commenced; no all out assaults for "Ould Maloney"!. The Nepalese, whose heaviest guns were wall-mounted jingals, were totally outgunned and their commander, Chumra Rana, after having ordered the bulk of his force to break out, surrendered with 100 men. Ochterlony carried out a night march to arrive before the main Nepalese position at Rangarh, where Amarsing Thapa was entrenched with 3000 picked troops. Again, Ochterlony rejected a frontal attack and decided to send the bulk of his forces around the Nepalese left flank while his artillery and one battalion occupied their front. Unfortunately, the fire of the artillery was totally ineffective and the senior engineer officer of the force, Lawtie, led 100 sepoys forward in a reconnaissance-in-force to see how the guns could be more effectively employed. This small force succeeded in over-running an enemy breastwork but were attacked by an overwhelming force and, having blazed off all their ammunition at long range, broke in rout before the Gurkhas reached them. However, the flank march forced Amarsing to withdraw from his position to another, even stronger, at Malaun. Amarsing's forces were now suffering severely from desertion as local chiefs began to change sides and assist the British invaders, while Ochterlony carefully brought up supplies, built roads and destroyed a series of small enemy strongholds. The Battle of MalaunThe position at Malaun consisted of a range of bare hills interspersed with fairly formidable peaks. The Nepalese right was protected by the fort of Soorujghur and the left by the great citadel of Malaun, while all of the peaks in between were topped with stockades, except for Ryla and Deothul.  Ochterlony now decided that the time for boldness had come and, on the night of April 14/15th 1815, the ubiquitous Lawtie led a handful of men up to Ryla peak and set about building his own stockade on the summit. At dawn five columns moved forward, three heading into the centre of the Nepalese position at Ryla, while Colonel Thompson led two more towards Deothul, which he took without difficulty having thrown out a flanking force under Captain Fraser to distract the enemy forces in front of Malaun; Captain Fraser was killed in hand-to-hand fighting but the Nepalese were unable to move to defend Deothul. Thompson began entrenching his position on the peak, which was strengthened by the arrival of two field guns. Bucti Thapa, who commanded the Nepalese forces between Ryla and Deothul, succeeded in slipping through the British lines in the night and joined Amarsing in Malaun, where they planned an attack to retake the Deothul position, which he would command. Bucti swore an oath to conquer or die and ordered his servants to prepare his funeral pyre before going to take command of the 2000 men earmarked for the assault. At dawn on the 16th the first wave went in against Thompson's two native battalions and two guns and were swept away in a hail of fire. A second charge was also wiped out and only a handful of men reached the British ramparts before they were cut down. Undaunted, a third wave went in, with identical results. Bucti Thapa, true to his oath, gathered a few men around him and led a final charge up the hill but was met by a counter-charge by the sepoys and his force was wiped out, Bucti Thapa being bayonetted to death. The total Nepalese casualties were enormous, over 500 dead were found on the slopes of Deothul; British casualties were also heavy, more than 300 being killed or wounded and the gun crews were so badly hit that, at the end, one was being served by Lieutenant Cartwright and the only unwounded gunner, while the other was crewed by Lieutenant Armstrong of the Pioneers and Lieutenant Hutchinson of the Engineers. Thompson had Bucti Thapa's body wrapped in a shawl and sent it to Amarsing as a mark of respect for a very gallant foe. The next day, a truce was observed as the body was cremated in the valley between Deothul and Malaun. Malaun was besieged and, when he was down to his last 200 men, Amarsing asked for terms and, in return for giving the British all the land between the Sutlej and Sarda rivers, the Terai, Kumaon, Garhwal and Simla and accepting a British Resident in the capital, was allowed to march out with all the honours of war. However, on arriving in Kathmandu, he recommended that the treaty be ignored, an approach which was in agreement with the feelings of the Nepalese government, who were unhappy with the idea of losing much of their personal revenue. THE CAMPAIGN OF 1816Lord Hastings, the Governor-General, resolved to bring the Nepalese into line once and for all; Ochterlony, now Sir David Ochterlony K.C.B., was ordered to march on Kathmandu with 14000 regulars, 4000 irregulars and 83 guns. Without waiting for a formal declaration of war, he set off through the Terai, his force divided into 4 brigades. Colonel Kelly of the 24th Foot commanded 4000 men consisting of his own regiment and several Indian units and was sent to the right flank to force his way through the Bagmatti Gorge. Colonel Nicholl was ordered to the left of the main body with the 66th Foot and 3800 Indian infantry to force his way up the Rapti valley while Ochterlony himself, with the remaining two brigades consisting of the 87th Foot and seven and a half Indian regiments totalling 8000 men, was to force his way up the direct road to Kathmandu via the Bichia Koh pass. On February 10th Ochterlony had reached the entrance to the pass and camped there opposite the Nepalese defences while his scouts went in search of a path which could be used to turn the position. This policy paid off when Captain Pickersgill encountered a group of salt smugglers who showed him a secret route. Led by the light company of the 87th, the entire 3rd Brigade and two elephants carrying an artillery piece each set off to outflank the pass on the night of February 14th. At 7am they arrived behind the Nepalese positions, which were then abandoned by their defenders and the 4th Brigade then marched up the pass to join their colleagues. Meanwhile, Colonel Kelly was besieging the fort of Huriharpur, which was held by Runjoor Singh and a small force while Colonel Nicholl was carrying out an unopposed march up the Rapti valley. On February 27th, Ochterlony arrived opposite a position at Makwanpore which was occupied in some strength by the enemy. During breakfast on the 28th, two men of the 87th Foot wandered out beyond the British pickets and into the fortified village on the Nepalese right, which they found to be deserted. Returning to their own lines, they were brought before their colonel and told him of their discovery. The colonel and Ochterlony immediately set out with the light companies of the 87th and the 25th Native Infantry and occupied the buildings while Pickersgill, Lieutenant Lee of the 87th, Lieutenant Turrell of the 20th Native Infantry and 20 men were sent to reconnoitre the fort at Makwanpore.  Leaving behind most of the men as a rearguard, Pickersgill pressed on with two companions up the jungle covered approach to the fort. Meanwhile, the Nepalese had realised what had happened and sent out a force to retake the village; this force fell on Pickersgill's rearguard and over ran them, killing Lee. The remnants retreated back to the village with Corporal Orr and Private Boyle forming the rearguard. The rest of the 87th had now arrived in the village and their fire stopped the Nepalese attack dead at a small ravine in front of the village. The Nepalese now prepared to attack with all their forces and Ochterlony hurried up two Indian battalions while the artillery in the British camp played on the enemy masses. Fighting with their usual bravery, the Nepalese crossed the ravine and carried out a series of assaults against the village, suffering immense losses. As assault after assault was mown down the Gurkhas began to waver and, at 5pm, Ochterlony sent the 8th Native Infantry to sweep them away. Attacking in line, this unit routed the enemy who fled in total disarray, leaving over 500 dead on the field; the total British losses for the day were around 250. Hard on the heels of the news of this disaster, the Nepalese government learned that Runjoor Singh had also been routed at Huriharpur and that Nicholl had joined Ochterlony, who remained encamped at Makwanpore. This was too much for them and they decided to make peace, the treaty being signed at Makwanpore on March 4th 1816. Under this treaty the Nepalese agreed to the same terms that Ochterlony had agreed with Amarsing nearly a year before; many brave men had died for nothing. During the war, Lieutenant Young, who had cradled the dying Gillespie at Kalunga, was selected to raise a force of 2000 Gurkha irregulars to fight for the British. In their first action this unit broke and ran and Young was left isolated amidst the enemy, who asked him why he hadn't fled as well. "I have not come so far to run away, I came to stop." he replied and sat down on a rock. His captors were impressed by such coolness and one of them observed, "You should be one of us, we could serve under men such as you." Taken to Kathmandu, Young was treated as an honoured guest and was soon fluent in Nepalese. When the war ended he was freed and placed in command of a prison camp at Dehra Dun. Undeterred by his previous experience he requested permission to raise another Gurkha regiment from among the prisoners; 3000 men volunteered for the unit, which was to become the Sirmoor Battalion, later the 2nd Gurkha Rifles, the first of a long line of Gurkha regiments to serve in the British army. BibliographyShipp, John Memoirs, London 1864.

Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #11 Back to First Empire List of Issues Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List © Copyright 1993 by First Empire. This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com |