The Battle of Neumarkt

24 April 1809

by Jack Gill, U.S.A.

| |

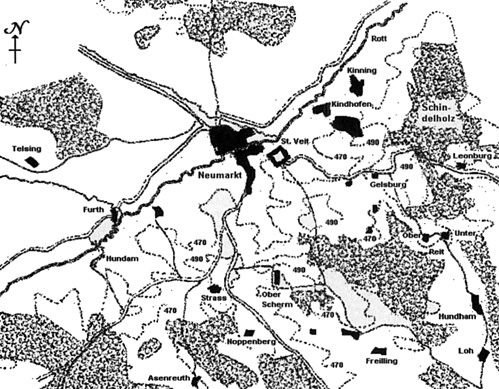

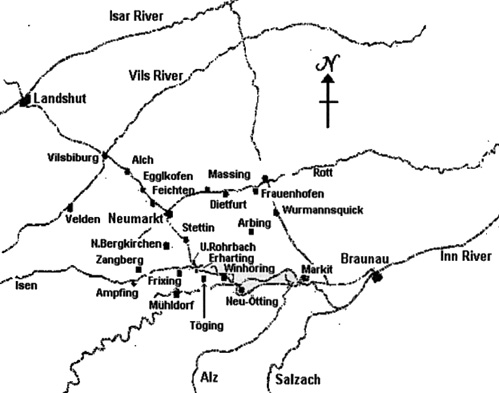

Prologue: The 6th Light InfantryThe green clad Bavarian light infantrymen waited crouching in the cool, silent darkness, straining to hear the distinctive sound of approaching hooves. Some little time earlier, breathless French chasseurs and their panting horses had hastened by in ones and twos, pausing only to say that more of their comrades were following. Even the main body of the regiment, trotting out of the twilight gloom like mounted ghosts, only halted briefly. There are others behind us, they said, as their horses blew and pawed impatiently at the road, some rear guard perhaps, but after them only Austrians, hussars. The Bavarian officer nodded and gave urgent commands as the French passed on to the north into the closing April night. Two Bavarian companies quickly deployed 20 paces from the eastern edge of the road and tucked themselves away among the brush and low trees; an outpost waited on the highway: an unknown sergeant and three men in the utter blackness. Before long, the clatter of cavalry could be heard to the south and the men tensed, but the sergeant boldly shouted his commanding `Wer da?' when the horsemen were 20 paces distant. The reply, however, was not French but rather a coarse Hungarian curse and the outpost ran for cover as the waiting infantrymen poured a heavy volley into the unsuspecting hussars. The Austrians fled. Satisfied that they had delayed the enemy sufficiently, the Bavarian officers were forming their men on the road when the hussars returned at the gallop. Caught unawares, the foot soldiers scattered into the nearby fields, clambering over fences and hedges to escape the Habsburg sabres. For a moment, all was shouting, scrambling and slashing. Then muskets flashed in the darkness and Austrian saddles emptied. The Bavarians, regaining their composure, drove off the horsemen and withdrew to the north through the night. As dawn was creeping over the eastern hills, the exhausted light soldiers rejoined their division on the heights south of Neumarkt. PreludeOn 10 April 1809, Archduke Charles had invaded Bavaria at the head of the Austrian Main Army (Hauptarmee). Although the French and their German allies were not yet fully prepared for war, Charles's advance was hesitant and his dispositions faulty. Napoleon seized the initiative as soon as he arrived in Bavaria and on 20 and 21 April, he battered the Austrian left wing and drove it back over the Isar River at Landshut. Although the situation was not entirely clear, Napoleon soon realised that he had split the enemy into two pieces: the shaken left wing retreating toward the Inn River and the remainder of the Main Army collecting itself south of Regensburg. With typical decision, Napoleon headed north from Landshut with the bulk of his army early on 22 April to strike Charles before the Austrians could escape over the Danube. As the long, muddy columns surged north out of Landshut, Napoleon detached Marshal Jean Bessieres with an ad hoc pursuit force to keep the pressure on the retiring Austrian left. Bessieres had immediate command of General-Leutnant Carl Phillip Freiherr von Wrede's 2nd Bavarian Division and some six light cavalry regiments under General de Brigade Jacob Marulaz and Charles Jacquinot, but he also had authority to call on General de Division Gabriel Molitor's French infantry division (still north of the Isar) in an emergency. Skirmishing with Austrian rear guards, the French and Bavarians pressed south through the 22nd, but the confident Bessieres granted his weary foot soldiers (and the Austrians!) a rest day on the 23rd, while Marulaz probed ahead toward the Inn. By late afternoon, his command was stretched from the Vils to the Isen: Molitor at Vilsbiburg; Wrede, Jacquinot and the 23rd Chasseurs north of the Rott at Neumarkt; Marulaz to the front with the 3rd Chasseurs toward Winhoring, 19th Chasseurs behind them at Erharting, and the Hessian Chevauxlegers north of Muhldorf; the Bavarian 6th Light Infantry and the 2nd Chasseurs moved to Unter Rohrbach to support Marulaz. Major Harscher guarded the left flank with two squadrons (1st and 2nd) of the 3rd Bavarian Chevauxlegers at Frauenhofen. Having rested his men, Bessieres planned to force a crossing of the Inn on the 24th against what he assumed to be minimal opposition; from his perspective, all was proceeding well. Collecting itself south of the Inn around Neu-Oetting was the somewhat stunned Austrian left wing. Under the orders of Feldmarschall-Leutnant (FML) Johann von Hiller, this force consisted of Hiller's own VI Corps, Archduke Ludwig's V Corps, and FML Michael von Kienmayer's II Reserve Corps; all were much reduced by detachments and casualties. Hiller had been out of communication with Archduke Charles since the 20th and was thus completely ignorant of the reverses Napoleon had inflicted on the Main Army at Eggmuhl and Regensburg. Unaware that Charles was retreating north-east into the Bohemian mountains, Hiller believed his duty lay in attacking Bessieres (whose strength he underestimated) and rejoining the Main Army (which he assumed was still south of Regensburg). Taking advantage of the weak pursuit on the 23rd as Bessieres rested his troops, Hiller managed to instil some order in his 31,000 men and prepared to take the offensive. In typical Austrian fashion - that is, reminiscent of Frederickian warfare - Hiller basically ignored the new corps structure as he organised his command for its counter-attack. His complex disposition established a main body of three `columns' and two flanking forces. Covered by an advance guard under General-Major (GM) Josef Freiherr Mesko von Felso-Kubinyi, the main body was to advance cross the Isen at Erharting (1st and 2nd columns) and Frixing (3rd column) and move north to occupy the heights south of Neumarkt: the 1st column just east of the main road, the 2nd along the road itself, and the 3rd further west through Nieder Bergkirchen. GM Josef Graf Radetzky would push north from Wurmannsquick to Eggenfelden on the right, supported by GM Josef Reinwald's little detachment from Marktl. GM Armand von Nordmann would protect the left flank by crossing the Isen at Ampfing and probing toward Velden. The tiny remnant of II Reserve Corps (five grenadier battalions and four squadrons of dragoons) would follow the main body as reserve. Finally, FML Karl Freiherr von Vincent, whose function had apparently been reduced to commanding a lone cavalry regiment, was to bring this unit, the Rosenberg Chevauxlegers (No. 6), from Arbing to join the main body. Which brings us back to the men of the Bavarian 6th Light Infantry staring into the gathering dusk near Unter Rohrbach on the evening of 23 April. To ease the next day's deployment from behind the Inn, Hiller sent Mesko and Nordmann toward Erharting and Toging respectively on the evening of the 23rd. Mesko's light troops, assisted by the Liechtenstein Hussars (No. 7) of Nordmann's command, pushed back Marulaz's cavalry screen and advanced through the darkness toward the 6th Light's positions above the Isen (two companies were along the road, the other two waited in support somewhat further north). The Bavarians lost about 40 casualties in the ensuing engagement, but they performed admirably, shielding the withdrawal of the Allied cavalry and earning Marulaz's gratitude: `The retreat was supported by a Bavarian battalion which comported itself with extreme valour.' Marulaz pulled his squadrons back north of Neumarkt to gain the protection of Wrede's Division. Here they were joined by the Hessian troopers who had been withdrawn after a brief encounter with Nordmann's patrols. The men of the 6th Light also closed on Neumarkt, establishing a picket line from Ober Scherm to Leonberg. To the right of the light infantry, the 13th Infantry covered Ober Scherm and Strass. Of Jacquinot's regiments, the 1st Chasseurs-a-Cheval were on the right of the 13th and the 2nd assumed outpost duty in the vicinity of Stetten; the location of the one or two 8th Hussar squadrons is not known for certain, elements were probably with the brigade while others reconnoitred near Ampfing and Muhldorf. BattleHiller's attack columns were plagued by delays in the predawn hours of 24 April. First, they were an hour late moving out, leaving their bivouacs at 3 a.m. instead of 2. Second, once the cumbersome crossing of the Inn had been accomplished, they found that Mesko's men, still in their original positions, were blocking the road north. Things were eventually straightened out, but Hiller decided to leave both the 1st and 2nd columns on the main road in an attempt to make up for the lost time. The 3rd column kept to the original plan, but, last to cross the Inn and assigned to secondary roads, it remained far behind the other two. Despite these problems, between 7 and 8 a.m., Mesko's patrols were in Stetten and Jacquinot's outposts were falling back on Neumarkt. The French cavalry had advised Bessieres of the unex pected Austrian advance at about 4 a.m. and the French marshal, hoping to defeat the overbold Austrians, ordered Wrede to form his division on the hills south of Neumarkt. Wrede was less sanguine. In his eyes, the situation was dangerous: the unfordable Rott was spanned by only a highway bridge and a narrow foot bridge. These could only be approached through the twisting and narrow alleys of the town, and, if withdrawal became necessary, Wrede feared congestion, confusion and heavy losses. Bessieres none the less ordered the Bavarians south of the stream nd sent couriers hastening to Molitor's Division at Vilsbiburg. Wrede thus brought the 3rd, 6th and 7th Infantry Regiments across the Rott at around 7 a.m. Preysing's cavalry and Dobl's heavy battery were left north of the stream with Marulaz's men. By 9 a.m., the 2nd Bavarian Division was deployed as follows: 13th Infantry and two batteries (Caspers and Dorn) astride the main road between Strass and Ober Scherm; in the woods on their left was one company of the 3rd infantry; the 6th Light and Berchem's battery in the woods northwest of Reit; two companies of the 3rd Infantry at Geisberg; II/3 at Leonberg; and the final 3rd Infantry company further north in the Schindelholz. Jacquinot's two chasseur regiments covered the approaches west of the 13th Infantry. GM Karl von Beckers deployed his brigade across the main road in reserve, 6th Infantry on the right, 7th on the left; two companies of the latter being detached to hold the St. Veit monastery as a strong-point. These deployments took some time, however, and Beckers's men were still moving up when the battle began in earnest. Off on the Austrian right, FML Vincent and the Rosenberg Chevauxlegers had arrived near Reit at about 8 a.m. and manoeuvred to occupy the attention of the Bavarian left. Along the main road, the Kienmayer Hussars (No. 8) of Mesko's advance guard were bolder, but their attempts to brush past the 13th Infantry were quickly driven off by the accurate fire of the Bavarian artillery. Their infantry supports (the Broder Grenzer (No. 7) and eight companies of Lindenau (No. 29) from FML Heinrich XV Reuss-Plauen's 1st column) could do no better. Help was soon at hand, however, as GM Friedrich von Bianchi brought his brigade into action. Advancing directly toward Ober Scherm under heavy fire, the Duka Infantry (No. 39) suffered badly and made little progress, but Bianchi got some of his guns up and sent two battalions of Gyulai (No. 60) into a wood that formed the seam between the 13th and the 6th Light. Despite a determined defence by the Bavarians, the Hungarians of Gyulai were able to advance quickly, outflanking Ober Scherm as Duka stormed it from the front. By 10 a.m. the village was in Bianchi's hands and the 13th Infantry's left was unhinged. Wrede was equal to the crisis. Quickly perceiving the danger to the integrity of his defence, he wasted no time in restoring the situation. He sent three companies of the 6th Infantry to the right to shore up the 13th's line around Strass, where GM Otto Graf Hohenfeld's Brigade (Klebek No. 14 and Jordis No. 59) was deploying west of the main road: two of the companies advanced in skirmish order to hold Hohenfeld in check, while the third covered the two batteries. These guns formed the core of the defence, delaying Hohenfeld and battering Duka's left flank with a storm of shot and canister. Shaken by this gunnery and disordered by their advance through the village and broken terrain, the Hungarians were unable to resist a sudden counter-attack by four other companies of the 6th Infantry. Bianchi's men were soon tumbling to the rear in some disorder and, by about 10.30, the Bavarians were once more in control of Ober Scherm. Some of Jacquinot's chasseurs apparently assisted in the attack but were driven off when they tried to seize a pair of Austrian guns. Almost immediately, however, a new danger threatened Wrede's command. While Bianchi was moving on Ober Scherm, FML Reuss was leading the rest of his column - a battalion of Gyulai in the lead, followed by a battalion of BeauIieu (No. 58) and the four remaining companies of Lindnenau - off to the right in an effort to outflank the Bavarian position; the other battalion of Beauiieu remained behind near Loh to act as a reserve. Passing through Hundham, Reuss's force came under heavy artillery fire from Hauptmann Maximilian Berchem's Battery but pressed ahead despite the crashing shot, the Gyulai battalion toward Geisberg, the men of Beaulieu toward Leonberg. The 6th Light initially fell back before Gyulai's attack, but Oberst Graf Berchem of the 3rd Infantry threw his reserve (two companies plus the combined Schutzen of the regiment) into the fray and hurled the Hungarians back down the slopes. The Beaulieu battalion, however, was more successful, and Oberst Berchem, now without a reserve, was forced to pull back. The 3rd Infantry's Leib Company, cut off as the Austrians advanced, lost an officer and 42 men before escaping. Never the less, Reuss's troops, disordered by the fighting and difficult ground, made slow progress and the Bavarian left was able to reestablish itself near St. Veit. At the monastery, the Bavarians received welcome reinforcement from Molitor's Division. The French general, alerted early in the morning, had arrived north of the Rott around 9 a.m. and deployed his division in line along the heights: 2nd and 16th Regiments north of the road, 37th and 67th to the south. At Wrede's request, Molitor had immediately detached four companies of the 2nd Ligne down the Rott to Dietfurt to back up Major Harscher and now, perceiving the threat to Wrede's line of retreat, he sent the General de Brigade Francis Leguay with the rest of 2nd Ligne across the stream to support the Bavarian left. The time was now between 11 a.m. and noon and the situation on Wrede's right was deteriorating rapidly. The Beaulieu battalion Reuss had deposited at Loh had managed to stabilise the Austrian centre after Bianchi's retreat and increasing numbers of white-coats were deploying south of Strass. Specifically, GM Nikolaus Graf Weissenwolff's Brigade was advancing through Asenreuth on Hohenfeld's left. Weissenwolff diverted his lead battalion (of Deutschmeister No.4) and his brigade battery to the right to outflank Strass but, fortunately for the Bavarians, adhered strictly to Hiller's disposition and pressed on for Furth with his remaining infantry. The Austrian penchant for focusing on terrain objectives and blindly following instructions thus once again assisted their enemies. Nevertheless, Wrede's left and centre were in serious trouble: between Strass and Ober Scherm, his four battered battalions and two batteries faced over 20 Habsburg battalions and 5 to 7 batteries. It was high time to withdraw and, at about noon, Wrede gave the signal to retire over the Rott. RetreatThe Bavarian withdrawal coincided with a renewed Austrian attack as FML Kottulinsky finally decided to commit his men to the struggle. Fortunately for Wrede, the Austrian general only risked one battalion (I/Klebek) which pushed in to Strass after skirmishing with the Bavarian rear guard. The loss of Strass, however, made the position at Ober Scherm untenable and the remaining elements of the 6th and 13th Regiments had to fall back. All Wrede's coolness and tactical skill was required to extricate his division from this difficult situation. The approaches to the bridge through the town's winding alleys were quickly clogged by retiring Bavarians, and the French 2nd Ligne, trying to cross south, only made matters worse. To the hard-pressed men of the 7th Infantry, however, whom Wrede had entrusted with the task of protecting the retreat, the arrival of the French regiment, rapidly reinforced by three voltigeur companies from the 16th Ligne, represented a welcome assistance. Supported by elements of the 13th, six companies of Lowenstein held the enemy at bay outside the village while the other two companies defended the monastery of St. Veit. Wrede was everywhere, giving orders, directing movements, inspiring his men by his presence and competence. He repeatedly led the 7th forward to gain time for the rest of his division to escape. In one of these counter-attacks, Oberst Friedrich Graf von Thurn und Taxis, who had only commanded the 7th Regiment for five days, was killed and numerous other officers wounded. Although his hat was pierced by a musket ball so that `the feathers flew about like snow flakes', Wrede left the battle unscathed. Kottulinsky now threw Jordis into the fight on the right of Klebek and his regiments were able to push the remaining Bavarians back into the town. The obstinate resistance of the Bavarian infantry and artillery, however, had allowed the 3rd Infantry, 6th Light, II/7, five companies of the 6th Infantry, the French troops and most of the Bavarian guns (half of Berchem's Battery excepted) to retreat safely across the river. As the Bavarians attempted to reorganise behind Molitor's lines, the French reformed on the northern bank to support the continuing withdrawal. By now the scene in Neumarkt was chaotic. The narrow alleys were crammed with men, horses, guns and wagons, all under the fee of Austrian artillery and skirmishers. In the tense confusion, mistakes were made. Thus Jacquinot's cavalrymen were left at the end of the march column. Jammed together amongst the buildings, they were unable to defend themselves and suffered severely when Austrian infantry broke into the streets. Shot, bayonetted or dragged from the horses into captivity, the 2nd Chasseurs took especially heavy losses and the fleeing fugitives of this disaster greatly increased the disorder at the bridge. With Austrian pressure mounting minute by, minute, Wrede collected the 38 chevauxlegers of his escort (of the depot of the 2nd Regiment) and charged the Austrians to gain a few additional minutes for the desperate retreat. Even so, the last three companies of the 6th Infantry found themselves crossing the bridge under fire from Austrian skirmishers who had crept to within 30 metres of the span. The men of the 6th were able to escape to the north, but the 13th was not so lucky; about 100 of its soldiers were taken prisoner near the bridge. Sergeant Schmidt of the 7th Infantry, trapped in the congestion, only saved his regiment's standard by leaping into the river and swimming to the opposite bank. Gradually, however, Wrede was able to gather his troops on the north bank of the Rott and, at about 3 p.m., the Bavarians fell back on Aich under the protection of Molitor's regiments. Hiller did not pursue, but Weissenwolff, still following the original disposition, had finally put his brigade across the Rott at Furth. Molitor deployed a battalion of the 37th Ligne in the woods north of Teising while the rest of his division retired along the main road in perfect order. French and Austrian skirmishers snapped at one another as the 37th joined the withdrawal, but the bulk of Weissenwolff's Brigade halted in Teising. The 3rd Austrian column, under GM Josef Hoffmeister von Hoffeneck arrived long after the battle had ended; it crossed the river above Furth and bivouacked south-west of Teising. Reuss also posted some vedettes across the river and Mesko, after much stalling and complaining, finally set out to follow Bessieres at about 6 p.m. He sent patrols as far as Egglkofen, but found it occupied and retired to Feichten for the night. FlanksIt had been a difficult day for the Bavarians, but Major Harscher brought back one bit of good news when he and his two squadrons rejoined the 2nd Division that evening. Posted during the day to watch the left west of Eggenfelden, they had fought a delaying action against Radetzky's Austrians along the Rott throughout the afternoon. Although they had lost some 80 head of cattle, they and four companies of Molitor's infantry had conducted a superb delaying action and had even managed to capture about 150 Austrians before they received word of Bessieres' withdrawal and broke off the engagement. Radetzky halted north of Massing. GM Reinwald moved to Wurmannsquick and placed a four-company detachment (III/Mittrowsky) in Eggenfelden. On the Austrian left, GM Nordmann encountered little contact with the enemy. With patrols out toward Velden, his command spent the night at Zangberg. ResultsThe battle at Neumarkt was an irritating setback for Bessieres and a costly one for the Bavarian 2nd Division. The marshal's insistence on fighting south of the Rott with a difficult defile to the rear cost the Bavarians heavily, and it was only thanks to Wrede's personal courage and the steadfastness of the Bavarian and French soldiers that the defeat was not a disaster. The Bavarians had shown themselves to be reliable, dedicated soldiers. Tenacious in defence, they also demonstrated tactical flexibility and performed well in skirmish order. The skill and determination of the artillery was particularly noteworthy, as was the relative order with which the difficult withdrawal through Neumarkt was conducted. The Austrian soldiers had also done well, attacking `with rare impetuosity' in Wrede's words. Habsburg leadership, on the other hand, had contributed little to the success. Although Hiller can be credited with considerable determination in organising his demoralised wing and attacking his pursuers, there is no evidence that he made any effort to control the battle. His subordinate commanders were equally unimaginative and there appears to have been almost no coordination among the various attacking columns. It was a battle won by superior numbers and soldier level courage. Both sides had paid heavily for their courage. The Bavarians lost between 1,000 and 1,200 men killed, wounded, and missing, but were able to recover some of the wounded when they reoccupied Neumarkt on the 26th. Monitor's casualties included some 20 dead, 172 wounded, and an unknown number taken prisoner. Jacquinot's exact losses are not known; we have only Bessieres' report that approximately 200 were hors de combat as a result of the battle. Combining these figures gives a total of some 1,400-1,600 casualties for the allied command on 24 April, although some estimates put the figure as high as 1,900. Austrian losses were lower, numbering about 1,400 (170 killed, 710 wounded, 510 missing or captured). The regiments suffering most were those involved in the fighting around Strass and Ober Scherm, particularly Duka, Lindenau, and Beaulieu. Hiller was unable to exploit his success at Neumarkt. During the night he received word of Archduke Charles's retreat into Bohemia and, early the next morning, his columns were headed back south toward the Inn. Bessieres, chastened by the events of the 24th and confused by the contradictory reports he received, kept his force in the vicinity of Vilsbiburg until the arrival of the fiery Marshal Jean Lannes got the pursuit moving again at mid-day on the 26th. In addition to holding up the French, however, Hiller had also delayed his own withdrawal by at least two days. In the opinion of the official Austrian historians of the campaign (Krieg 1809, vol. III), he thereby inadvertently lost the time he might otherwise have used to establish a planned defence along the line of the Inn and Salzach Rivers. His decision to counterattack, therefore, though reasonable, indeed commendable, when it was made, allowed Napoleon to cross the Inn almost unhindered and nearly resulted in Hiller's entrapment between that river and the Traun in the first days of May. Bavarian Unit OrganizationInfantry: Each company numbered approximately 180 bayonets including 20 Schutzen. Organised into field battalions of four companies (three line, one grenadier); each battalion also had a depot company at home station. Battalion or regimental Schutzen often combined for tactical purposes. Regiment comprised of two battalions. Regiments started the war with about 1,600 men in the ranks. Light Infantry: Four field companies, each of circa 180 bayonets. Depot company at home station. Battalions bore names of commanders. Cavalry: Each regiment consisted of four squadrons. Squadron strength at the start of hostilities about 125 troopers. Artillery:

Line Battery. Four 8-pdrs, two howitzers. Gun crews walked. Reserve. Four 12-pdrs, two howitzers. Battle of Neumarkt 1809 Order of Battle Principal SourcesBuat, E. 18O9 De Ratisbonne a Značn, 1909.

Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #11 Back to First Empire List of Issues Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List © Copyright 1993 by First Empire. This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com |