On the 6th of February 1794, in response to a near desperate plea from the Government, the

Directors of the East India Company agreed to turn over to the Board of Ordnance all its new arms together with those under contract, for use by the rapidly expanding British Army. By the end of that year no fewer than 28,920 muskets had been delivered together with a not inconsiderable quantity of fusils, carbines, wall-pieces, pistols and even 5,000 copies of the French Model 1777 Charleville set up by the Birmingham contractors Galton and Whately had been delivered to the Tower [1] and smaller quantities were aquired in later years.

The "INDIA PATTERN" [2] was rather easier to set up than

the Short Land Pattern Musket and gunmakers were therefore given open contracts in 1794 and

1795 to deliver to the Tower as many of this pattern as possible and in 1797 production of the Short Land Pattern ceased entirely when all resources were concentrated upon the manufacture of the India Pattern.

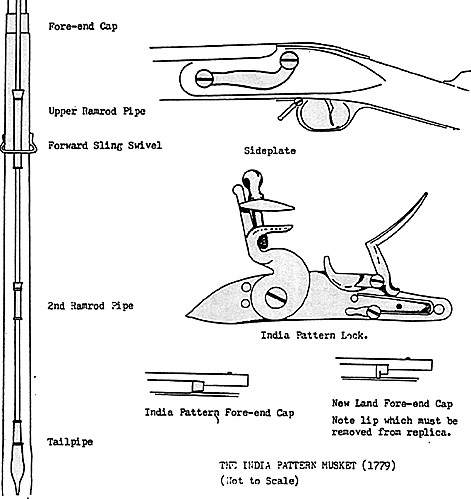

This pattern fireiock was by no means new in 1794 having first been set up for the East India Company in 1779. In outlinc it fairly closely resembles the Short Land Pattern; the most

immediately obvious difference being a shorter barrel - 39" as against the 42" barrel of the Short Land Pattern - and the consequent re-arrangement of the ramrod pipes. This shorter barrel was not primarily as has sometimes been suggested an economy measure but was, like the choice of

"inferior" heart and sap grade walnut for the stock, intended to produce an appreciably lighter [3] and handier musket better suited to the Company's sepoys who were generally speaking shorter and less well developed than European soldiers.

The brass furniture was also rather simpler but again this could be considered to be an

improvement rather than a drawback. In the first place the shorter barrel and stock required only two rather than three ramrod pipes - besides the tail pipe. The upper ramrod pipe was the long trumpet shaped one introduced around 1750 when steel ramrods became standard on all new Long Land Pattern muskets [4] (Steel ramrods had first been

introduced in the 1720s but were only slowly fitted retrospectively to muskets actually in use).

Since the upper pipe had to be set back 3" due to the shorter barrel the forward sling swivel is attached to the stock at about the mid-point of the pipe. The juxaposition of ramrod pipe and sling swivel is perhaps one of the most readily recognisable features of this pattern musket. Moving the upper ramrod pipe back 3" also meant that the second pipe had similarly to be moved to a position midway between the upper pipe and the tailpipe with the result that the third ramrod pipe was dispensed with. [5]

This second ramrod pipe was of the small trumpet style devised by the London gunsmith John

Pratt in 1777 and theoretically aided the speedy return of the ramrod. The tailpipe followed the Short Land Pattern but the sideplate was much simpler and was modelled on that of the France Model 1777 Charleville. Lacking the "tail" of the earlier Land Pattern muskets it is another useful recognition feature although it should be noted that some late production Short Land Pattern muskets also featured it. [6]

The escutcheon plate on the wrist of the stock was ommitted from the India Pattern presumably because it had at last been recognised to be superfluous - rack and unit marks are more commonly found engraved or stamped on the butt-plate tang, or even the barrel of Land Pattern muskets with escutcheon plates. There were also some quite minor differences in the form of both trigger guard and butt-plate.

The only significant alteration occurred after 1809 with the substitution of a stronger

ring-necked cock for the original swan-neck cock. This change also affected muskets made

for the East India Company but it does not appear to have been universal since India

Pattern muskets were being set up with swan-neck cocks as late as Queen Victoria's reign in

the late 1830s. In general it might also be observed that the finish of late production

weapons is inferior. An India Pattern musket made in Dublin Castle in 1821 for the Sligo

Volunteers exhibits a good finish but another made for the East India Company at about

the same time is rather plain and lacks the carving around the breech normally found on

these weapons (both muskets are presently in the National Army museum).

[7]

There has always been a distinct tendency to regard the India Pattern musket with

something less than affection and to consider it to be a markedly inferior weapon to the

Short Land Pattern musket which it replaced. Some writers indeed have gone so far as to opine quite forcefully that it is unworthy of inclusion in the "Brown Bess family". Arguably the reverse is the case.

Although the precise pattern did not originate with the Board of Ordnance the India Pattern's parentage is obvious and to pretend that it is not simply a variant of the Land Pattern, just as the 1757 Short Musquet of the New Pattern for Marines or Militia was before it (it might not be inappropriate to comment that surviving examples of this pattern are certainly not superior in quality to the India Pattern and foreshadow a number of its features).

New Features

First set up in 1779, the India Pattern incorporated some new features such as Pratt's small

trumpet-shaped ramrod pipe and the French Model 1777 sideplate. The rest of the brass furniture is certainly less elaborate than that of the Short Land Pattern but if anything an improvement. The finish of early E.I.C. muskets appears quite good and although the later muskets are not always as good as the Long and Short Land Pattern muskets this might be more justly attributed to the pressures of wartime manufacture than to any intrinsic defect in the pattern.

On the other hand the advantages of lighter weight, handier length and easier construction far outweigh carping criticism of shortcomings which are quite literally superficial. The India Pattern musket was a good workmanlike firearm which served the British Army and the East India Company well in the long wars against France and against other foes around the world for three-quarters of a century - indeed it probably saw rather more service than any other Land Pattern variant. [8]

Although it is generally understood to have been adopted as limited standard in 1793 and to

have superceded the Short Land Pattern in 1797 (Short Land Pattern muskets continued in use for

some years afterwards of course) the India Pattern also seems to have seen some quite extensive

"unoffical" service with the British Army before 1794. It has sometimes been suggested that it is possible that it might have been issued to British soldiers in India since it was so similar to the Short Land Pattern.

This suggestion is not at all unreasonable since British regulars serving in India in the 18th century were in effect contracted to the East India Company who were in any case responsible for supplying them. Proof that this was in fact the case comes from Robert Home's magnificent painting of the death of Colonel Moorhouse at the siege of Bangalore in 1791. [9]

Painted in India no more than a year later it records the uniforms of the troops involved in

meticulous detail and soldiers of the regiments concerned must have been used as models. Of

greatest interest are a group of grenadiers and at least one light infantryman belonging to the King's 36th Foot. They are all of them armed with what are quite unmistakably India Pattern muskets rather than Short Land Pattern ones, thus anticipating the Board of Ordnance by at least two years. It is not yet known however whether the East India Company may have provided muskets for complete battalions as a matter of course, upon or shortly after their arrival in India or whether they were only issued to replace worn out weapons. [10]

There is also an intriguing possibility that the India Pattern musket may have seen some service with the army outside India before 1794. Muskets set up at the Tower or under Board of Ordnance contracts ceased to bear the gunmaker's name and year of manufacture engraved on the lock after 1764 but both the locks and barrels of East India Company weapons continued to be so

marked until the end of the 18th century. However aside from two or three insignificant variations nearly all surviving E.I.C. marked muskets which survive bear either the date 1779 or 1793.

It used to be suggested at one time, mainly it has to be said by enterprising American antique firearms dealers, that India Pattern muskets bearing the former date might have been used in the American colonies during the revolution after having been taken off captured Indlamen by rebel privateers. Anthony Darling on the other hand states quite firmly that evidence of this is lacking and suggests instead that the dates 1779 and 1793 are not dates of manufacture but contract dates. [11]

Such a proposition although neat does not really stand up. In the first place although much rarer other dates are to be found and there is in any case no material difference between the two. The very style of the marking also clearly points to it being a date of manufacture rather than a "model" or contract date.

The survival of those muskets bearing the date 1793 can in fact easily be explained since it is obvious that they must be some of the 29,000 muskets turned over to the Board of Ordnance by

the East India Company in 1794. The greater part of these were delivered in late February of that year and will naturally therefore have been muskets set up in 1793 and so marked.

The 1779 vintage muskets appear at first to be less easy to account for. Since they are so

dated on both lock and barrel it may fairly be assumed that they were set up in that year rather than assembled later using old parts. They are also unlikely to have formed part of the stock turned over in 1794 since the contract called in the first place for new muskets and if old muskets were still stored in any quantity one would expect to see a broader range of dates. Given that muskets shipped out to India are, with odd exceptions, unlikely ever to have been brought back to this country three possible explanations for the survival of the 1779 muskets remain

(ii) In 1779 as in 1793 there was a major war in progress and the Board of Ordnance was as

usual desperately short of muskets. [12] It is just possible

therefore that some limited aquisition of E.I.C. muskets may have taken place, perhaps for the

equipping of fencibles or American Provincial troops and militia.

(III) The simplest solution to the question may in the end be that refuted by Darling for he

appears to be unaware that although no large scale siezures of outward bound Indiamen were made

by American privateers there was in fact a disasterous encounter between a Franco-Spanish fleet

and an unprotected convoy off Cadiz in late July 1780. Amongst the prizes taken were five large

Indiamen laden with muskets and other warlike stores for Madras. Since the French, and to a lesser extent the Spaniards, were of course actively engaged at the time in supplying such commodities to the rebels it would be natural for them to pass these muskets on - in time for the Yorktown campaign in 1781 [13]. There is not sufficient space in this short article to adequately discuss the extent to which the India Pattern musket saw service with the British Army after 1794 but it is worth re-emphasising that the India Pattern and not the Short Land Pattern was the most widely used musket during the Peninsular War and that by the time of Waterloo very few Short Land Pattern muskets will still have been in use. [14] The New Land Pattern Musket, first set up in 1802 had been intended to replace the India Pattern but in the event comparatively few were ever produced and they were probably only issued to the Guards leaving the rest of the army to soldier on with the India Pattern until replaced by percussion muskets.

Modern reproductions of both the Short Land Pattern and India Pattern muskets are freely

available today and despite its costing little more than half the price of the former there is still unfortunately a tendency to regard the India Pattern as being markedly inferior. Some minor work is undoubtedly necessary to finish off the India Pattern replica and Pedersoli's Short Land Pattern replica is undeniably a handsome piece, but this ought to be outweighed for Napoleonic re-enactors at least, not merely by the fact that the India Pattern is more appropriate but by the fact that the particular model offered was set up for re-enactors of the American Revolution and its specification is inappropriate in any case for the Napoleonic period. [15]

D.W. Bailey British Military Lougarms 1715-1865 (1986)

I should also like to record my grateful thanks to Dr. Stephen Bull of the National Army Museum for the opportunity to examine the various India Pattern (and other) muskets in the collection there. Books and photographs arc useful but nothing can beat examining the weapons themselves.

[1] Blackmore p133 11c "Charlevilles" were issued to French emigre units

Since this article first appeared in the Napoleonic Association Journal, I

have had a letter from Richard Tennant of Eindhoven, describing an EIC

musket in his possession with a lock dated 1799 but a barrel, by Harrison,

dated 1777. Since the use of 39" barrels therefore pre-date 1779 the theory

that the pattern was first set up in that year must be discounted. Furthermore

although it is true that the sideplate closely resembles that on the 1777

Charleville it is equally true to say that although there are some minor

differences it also closely resembles the original Land Pattern sideplate less

the "tail' Since French muskets had featured a tail-less sideplate since the

beginning of the 18th century the India Pattern one can hardly be taken to

indicate a post 1777 date.

In the light of this it now seems likely that a firearm recognisable as the

India Pattern, featuring a 39" barrel and most likely a tail-less sideplate, was

carried by John Company soldiers well before 1779 and probably paralleled

the development of the Land Pattern series in the changeover from wooden

to metal ramrods and the form of the ramrod pipes.

Establishing just how far back the India Pattern does go will take some

considerable research but this does point once more to the 1779 dated

muskets having been set up in that year and captured en-route to India the

following year rather than simply bearing a contract date.

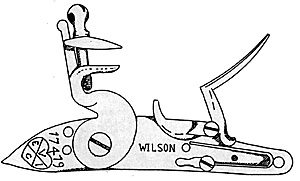

The lock was exactly the same as the later models of Short Land Pattern musket. The East

India Company's own muskets generally speaking have much plainer locks than those

manufactured under Board of Ordnance contracts.

The lock was exactly the same as the later models of Short Land Pattern musket. The East

India Company's own muskets generally speaking have much plainer locks than those

manufactured under Board of Ordnance contracts.

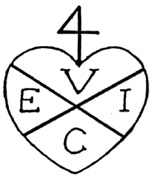

Engraved on the tail of the lock is the E.I.C. heart-shaped mark (see sketch) and the date of manufacture. While the maker's name appears on the middle under the flash-pan. (All three also appear on top of the barrel). Those made for the Board of Ordnance on the other hand feature the usual line engraving found on the Short Land Pattern, the word TOWER on the tail and a crown on the centre. (Barrels are quite plain, bearing only proof and acceptance marks - unless a regimental badge or title is added).

Engraved on the tail of the lock is the E.I.C. heart-shaped mark (see sketch) and the date of manufacture. While the maker's name appears on the middle under the flash-pan. (All three also appear on top of the barrel). Those made for the Board of Ordnance on the other hand feature the usual line engraving found on the Short Land Pattern, the word TOWER on the tail and a crown on the centre. (Barrels are quite plain, bearing only proof and acceptance marks - unless a regimental badge or title is added).

(i) The muskets were retained in Britain by the East India Company, possibly for the basic training of recruits for its European regiments.

Bibliography

H. Blackmore British Military Firearms 1650-1850 (1961)

A. Darling Redcoat and Brown Bess (1970)

Notes

[2] The term INDIA PATTERN first occurs in Ordnance records in 1794 but for convenience sake is used to designate the weapon from its first being set up in 1779.

[3] The Short Land Pattern musket weighs 101b 8oz as against the 91b 11oz of the India Pattern, a difference of very nearly a pound.

[4] Bailey p17

[5] Interestingly this two pipe arrangement can also be found on some Long Land Pattern muskets which have had their barrels cut down to 42".

[6] Darling pp 38, 40. Conversely a late production E.I.C. India Pattern in the National Army Museum has a New Land Pattern sideplate.

[7] see Bailey p95 fig.2

[8] Some British units in India still had the India Pattern musket as late as 1848.

[9] Now displayed in the National Army Museum. At least one modern reconstruction of a soldier of the 36th at Bangalore has been "corrected" to depict a Short Land Pattern musket in use.

[10] The Board of Ordnance seems to have reckoned the useful life of a musket as being about twelve years in normal circumstances. A higher rate of turnover might be expected in wartime or in tropical climes.

[11] Darling pp52, 54

[12] See Blackmore p62 An objection to this possibility lies in the fact that the 1779 E.I.C. musket was not then "Pattern". According to Blackmore the aquisition of E.I.C. muskets by the Board in 1794 was the first time that non-pattern weapons were purchased. This arguement is in turn somewhat undermined by the profusion of carbines and fusils aquired during the 18th century.

[13] A portrait by Gainsborough of an officer of the King's 4th Foot, thought to be Thomas Bullock, Lieutenant of the Light Company in 1779, depicts what may be an India Pattern fusil. Although slightly more ornate than usual the sideplate conforms to the Model 1777/India Pattern shape.

[14] The Short Land Pattern may indeed have disappeared fairly quickly. "Old Regiments" such as the 6th certainly still had it around 1802 but newer regiments such as the Strallispey Fencibles, raised in 1793 had India Pattern muskets long before that date - Seafield Collection, Fort George.

[15] The Pedersoli Short Land Pattern does at least have the

flat side-plate introduced in 1775 but otherwise the furniture, while acceptable, really belongs to the period before the introduction of the short trumpet shaped second ramrod pipe by John Pratt in 1777. The lock however is far too early. Not only does it bear both maker's name and date of manufacture (in this case GRICE 1762), features which disappeared after 1764 but it has the early style of cock and a trefoil finial to the Steel spring screw. Given a useful life of twelve years it is Inconceivable that a musket of this description would have seen service in the Peninsular War, far less at Waterloo.

POSTSCRIPT

India Pattern Musket, Accurising the India Pattern Musket

Back to 18th C. Military Notes & Queries No. 6 Table of Contents

Back to 18th Century Military Notes & Queries List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1999 by Partizan Press

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com