The name of Sir William Howe is familiar to any student of the American Revolution. As Commander of the British army in North America from 1775-1777 he is often viewed as the man who lost the American Colonies. Often overlooked are his contributions to the training and tactical use of that army. A surprising misconception, in spite of the available literature is the way in which the British infantry fought the American Revolution. All too often we hear about a noodle headed British officer in bright, scarlet uniforms who refuses to adopt "revolutionary" Indian tactics unheard of in European warfare. The redcoats stand in the open and are shot down by their concealed opponents. The truth is far more interesting than the fable, and a different side of Howe emerges from the shadows.

The British army had been introduced to this irregular style of warfare in North American and North Western Germany during the French and Indian War (or Seven Years War) 1755 to 1762. [1] In Germany, the British had relied first on the Freikorp & Jagers of their Hanovarian, Brunswick and Hessian allies to counter the irregular tactics of the French Chassaurs. Later in 1760 Keith's (87th) and Campbell's (88th) Highland Regiments [2] were raised to act as Light Infantry. About the same time in North America, the disaster that over took Braddock's column on the Mongnahela River in 1755 served as a rude awakening.

Not able to depend on German allies, and finding most Provincial units equally hapless, specialized units needed to be formed capable of meeting their irregular opponents on equal ground. [3] Tactics were needed to assist the line troops in dealing with irregulars.

Scouting Companies

Lord Loudoun, as British commander-in-chief in America set about this task with a vengeance. Scouting companies were formed from the better Provincial to provide long distance intelligence gathering. Promising line officers and enlisted men volunteered to go out on these 11 scouts" to learn the ropes. [4] They were then to return to their battalions and pass on what had been learned. In addition Colonel Gage raised the 80th Light Armed Foot, the first Light Infantry Regiment in the British Army. Lord Loudoun also raised a four battalion strong regiment called the 60th (Royal American). [5]

Here the men were dressed in converted uniforms adapted for the conditions in the Colonies. There was extensive training in "firing at marks" and moving quickly and in order through the woods. [6] And as in Germany, a Highland regiment (42nd) was sent to act as Light Infantry. They worked out so well, that three more Highland regiments (2/42nd, 77th & 78th) were in the field by 1759. [7]

In 1758 each line Regiment was requested to raise and add a Light Infantry company to it's establishment. They were to provide flank protection, march security, and deal with their enemy counterparts. [8] The Light Infantry companies were usually brigaded in composite battalions.

Colonel William Howe's Light battalion distinguished itself during the French and Indian War, incorporating their new training. They cleared the Heights of Abraham, silenced the Somas battery and enabled Wolfe to bring his army into play and win Quebec. The line battalions also altered their uniforms, and adopted a looser two rank deep line formation. [9]

By the end of the war the entire army had done a fine job in adapting to conditions. One has only to compare Braddock's disaster on the Monongahela River in 1755 with Bouquet's action at Bushy Run in 1763 in a very similar action to see how much the British Army had learned. [10]

End of Seven Years War

With the end of the Seven Year War came a reduction in the army. Many of the Highland regiments, the light companies, and the 80th light Armed Foot were disbanded. While the lessons learned were not forgotten, they were filed away. It was not until 1771 (on the English establishment, 1772 on the Irish establishment) that Light companies were again added to a regiment's establishment. [11] But they were uneven things, often used as dumping grounds and poorly trained. [12]

Accoutrements, dress and especially training were all haphazard. "It is not a short coat or half gaiters that makes a Light Infantry man," wrote Lord Townshend, "but as you know, Sir, a confidence in his aim ' & that stratagem in a personal conflict which is derived from experience." [13]

William Howe, who like Townshend had considerable experience with Light Troops in North America was equally upset over the quality of the "light Bobs." Reviewing the 4th Regiment of Foot in 1774 he reported they were ill supplied; that the Light company had ,, not been practiced in firing ball." Hard comments on the quality of troops whose bread & butter should have been skirmishing. The sad fact was that it took far more training to make a Light Infantry man than a common soldier. [14]

By 1774 the Army had begun its process of bringing the Light Companies into shape. A suggested set of uniform and equipment guide lines were set down. [15] Since in time of war these companies would to be taken from their parent battalions to form composite Light battalions a standard set of drill was needed. The Army turned to William Howe, whose reputation from the late war had made him the premier Light Infantry officer.

Drawing on his considerable experience Howe set about writing down a Light Infantry discipline that would combine speedy manoeuvre with skirmishing ability. The Light Infantry Discipline suggested that companies parade in two ranks.

Tactics

The files were to operate at the "close" (files together, elbow to elbow), "order" (files at two feet interval), "open order" (files four feet intervals), or "extended order". Movement was at the "march" (slow), "march march" (quick time) or "advance" (run) speeds. Changing from column into line or line into column would be done by files of two from the right, the centre or the left of a line.

Advancing and retiring by files were practiced by battalions in wings, divisions and platoons. Firing was done by the 1764 platoon regulations. The lack of practice in firing Howe had noted with the 4th was not to be found in his training camp. Everyone was issued 90 "squibs" or blanks and 20 ball cartridges.

The combined effect gave a Light battalion commander great flexibility in his dealing with any situation. [16] With a good Light Infantry discipline, it was now time to train the various light companies to a uniform system. Howe was to set up a number of training camps to instruct the light companies in his discipline. When finished they were then to return to their parent battalions to "spread the gospel" and teach other companies. The system would then enable battalion commanders to profit by picking up instruction for the line, as well as having all the light companies trained to operate together.

The first training camp was 6 August through 22 September 1774 at Salisbury. Six Light Infantry companies, from the 3rd, 11th, 21st, 29th, 32nd, 36th and 70th regiments were his first class. They drilled, trained and practiced the discipline through an endless series of skirmishes. Finally, on 3 October 1774 the troops put on an extensive demonstration of Light Infantry tactics in a very realistic review for the King at Richmond. The troops advanced and retired through woods, open fields, around buildings, by battalions, wings, divisions and platoons; in both loose and closed files. Reading the outline of the review gives the modern reviewer an outstanding example of how Light Infantry moved and fought during the time period. [17]

Those companies that returned to their regiments did pass on the training, while other companies not involved in the initial training also learned from it. Sergeant Roger Lamb, of the 9th regiment then stationed in Ireland talks at length about the training. He, along with a number of noncommissioned officers were all sent from their regiments to learn the new discipline, "preparatory to the general practice of it." The 33rd regiment then at Dublin had been set up as the training company. Lamb wrote about the discipline, that Howe's maneuvers were chiefly intended for woody and intricate districts, with which North America abounds, where an army cannot act in line. [18]

Lexington and Concord

But events in Boston Massachusetts through 1774 ended any other camps. Howe, along with two other ranking officers were sent in April to assist Gage with his increasingly deteriorating command.

General Thomas Gage in command at Boston had possibly encouraged some training of the Lights based on his experiences with the Old 80th Light Armed Foot. Dr. Robert Honeymoon, visiting from Virgia wrote on March 22, 1775 that he observed what sounds like Light Infantry at practice.

"Every Regiment here," wrote Honeyman, "has a company of light infantry, young active fellows; & they are trained in the regular manner, & likewise in a peculiar discipline of irregular & bush fighting; they run out in parties on the wings of the Regiment where they keep up a constant & irregular fire; they secure the retreat; & they defend their front while they are forming; in one part of their exercise they ly (sic) on their backs & charge their pieces & fire lying on their bellies. They have powder horns & no cartridge boxes." [19]

But no move was made to brigade the various Light Infantry and Grenadier companies into composite battalions. This prevented the different company commanders from working together, and gave no individual any experience in handling these unusual commands. The Companies stayed attached to their parent battalion and operated with them. [20] They were brigade and operated together for the first time on April 19.

Adding to the confusion, Howe's Light Infantry Discipline possibly arrived in Boston just prior to April 19, 1775. "The Grenadiers and Light Infantry Companies," recorded Adjutant Frederick

McKenzie of the 23rd Royal Welsh Fusiliers on April 15th, "were this day Ordered to be off duty 'till further orders, as they will be ordered out to learn the Grenadier Exercise, and some New Evolutions for the Light Infantry." [21] This order was repeated on April 16. At the fight at Concord's Old North Bridge the confusion among the British officers might be attributed to a poor understanding of the new drill; or confusion about old vs new commands.

No matter, April 19 been a poor day for the Light Infantry. Both the 10th & 4th companies had gotten out of hand and fired against orders on Lexington Green. Eight Americans were killed and ten others wounded. Then the 4th, 10th & 43rd companies attempt to defend the bridge had dissolved into confusion. The 4th company was collected again that day," wrote Ensign Lister of the 10th, "some of them joined our company and was permitted to remain..." [22]

Lord Percy, commanding the reinforcements

that joined the British in Lexington on their march

back used his own battalion company men as

flankers for the remainder of the march. [23]

Under Percy the battalion companies of the 23rd Royal Welsh Fusiliers had acted as rear guard. Adjutant Mckenzie from the 23rd had been mentioned in the orders of 16 April as instructing the Light companies in the new discipline, so it is possible that the entire regiment was familiar with it. Mckenzie's account of the 23rd acting as rear guard is text book Howe. "We immediately lined the walls and other cover in our front with some marksmen, and retired from the right of companies by files to the high ground a small distance to our rear, where we again formed in line [24]

The marksmen mentioned were drawn from the 23rd's battalion companies. The regiment had been extensively practising marksmanship. All winter they were quartered on a wharf, and had set up man sized targets on floats that were placed in the water. In addition objects in the water were pointed out to fire at as they moved up and down. "Premiums are sometimes given for the best shots, by which means some of our men have become excellent marksmen," wrote Mckenzie. [25]

Bunker Hill

Howe arrived in Boston on May 25, 1775. The Light Infantry were brought into a higher state of training under his command. At Bunker Hill after the debacle on the beach they successfully skirmish and pin down the American forces along the rail fence enabling Howe to over run the redoubt. [26]

Following the American retreat they conduct a harassing pursuit of them off the peninsular. On November 5 the Light Infantry battalion conduct a successful raid on Phipp's Farm on Leachmear point in order to capture some badly needed livestock for the Boston garrison's food supply.

On March 17, 1775 Howe evacuated Boston, and move the troops north up to Halifax. There he set up a further training camp. Keeping in mind the difficult terrain that would confront the army, and the lack of any sort of serious cavalry arm that would force the Infantry to fight closed up, the line battalions are trained to operate two ranks deep in both close and open order. [27]

This was something that only trained soldiers could do. Just as it is very difficult to march a battalion in a straight line that keeps it's order and formation, it is even more difficult to do so when the line is at open or extended order. Yet this is what Howe teaches the army, and the infantry learns to do it well. Because the open order line might run into trouble when confronted with a solid, compact formations the troops could fall back into a closed file type line. Major French, in his journals [28] during the war includes a drawing of how to change from two ranks into three ranks. Equally important the new Brigadiers are given time to learn their trade in commanding their Brigades. They are given valuable time to train the battalions under their command to operate together.

The Army is now made up of a very flexible Infantry who are commanded by Brigadiers used to working together. When he is finished, Howe's army is in excellent shape for the campaign with battalions and brigades that can operate and manoeuvre together effectively. "It does what Howe wants it to do, and does it well." [29]

Long Island

On Long Island the newly arrived Hessians are confronted with the strange sight of line battalions operating in open order in very thin lines two ranks deep. [30] The universal comments of the German officers are that they cannot keep up with them on the march across country. They found that the British, in their looser formations could advance faster. The Hessians, two ranks deep but closed up tight, fell behind the British about thirty paces for every hundred paces they advanced. [31]

The thin, open order lines moved quickly with less confusion over the broken terrain. Two rank order also maximizes the firepower of the line, while making it easier to manoeuvre over difficult, broken terrain. It is with this "loose files" and flexible style that the British Infantry operates throughout the war. "We have succeeded always (with it); the enemy have adopted it; they have no cavalry to employ against it." [32]

Not that it is popular with everyone. German and French observers think it too thin and brittle to operate in Europe. Cavalry and thicker three rank deep infantry will tear it up. [33] French officers are eager to have a go against it while employing their own tight, three rank deep lines. Clinton, Howe's replacement in 1778 writes after the war that he was never in favour of the "lose, flimsy order". He "had disapproved, particularly of the two-deep line, and had trembled for the consequences." Being too thin, Clinton made sure that he was 11 always supporting it with something solid.... The (solid) Hessian Grenadiers supported the advanced elements, which in turn supported the light troops making the assault. [34]

Clinton, while not present blames the British defeat at the Cowpens (1781) on the lose order.

"Victory... was suddenly wrested from him by an

unexpected fire from the Continental while the

King's troops were charging and sustaining (it) in

that loose, flimsy order which had ever been too

much the practice in America. [35]

Tarleton echoes this blames in his memoirs

(along with anything else he can think up) for his

defeat at the Cowpens in 1781 rather than his own

mishandling of the battle. Yet he is refuted by a

junior officer, who states that the defeat is through

his Tarleton's own incompetence rather than the

loose files which had been used so well on

countless battlefield both before and after. [36]

Clinton continued throughout his command to

employ the same formation he wrote about years

after the war was over.

The merits of Sir William Howe's responsibility for the loss of the American colonies continues to be debated. Overlooked time and again is his ability as a tactician. He successfully molded the army into a force that could fight and fight well in a new environment.

Looking into the future, the one thing carried into the early nineteenth century by the army was its ability to fight in long, thin, two rank deep lines. Howe created the building blocks that other expanded and used so well. And for this, as well as his role in losing the Colonies should he be remembered.

[1] Paret, Peter, "Colonial Experience and European Military Reform at the end of the Eighteenth century. Institute of Historical Research, XXXVI (1964).

See for argument that Light Infantry developed in Europe rather than in North America.

Author's note: the French got their chance in the West Indies against General Harris' American veterans and got a bloody nose for it.

Footnotes

[2] Atkinson, C. T.; "Highlanders in Westphalia 1760-62, and the Development of Light Infantry". journal of the Society for Army Historical Research, 20, 1941.

[3] Pargellis, S. M., Lord Loudoun in North America, New Haven, 1933, pp.300-1.

[4] Pargellis, S. Al., Military Affairs, 1748-1765: Selected Documents from the Cumberland Papers, New York, 1936, p.269. Rogers, Robert., journals of Major Robert Rogers: Containing an Account of the Several Excursions He Made ... Upon the Continent of North America (1765) pp.56-70.

[5] Parker, David., That Loose Flimsy Order: The Little War meets British Military Discipline In America 1755-1781. Master of Art in History Thesis, University of New Hampshire, 1988, pp.2634.

[6] Pargellis, Loudoun, pp.299-300.

[7] Houlding, J. A., Fit For Service: The Training of the British Army 1715-1795. Oxford, 1981, p.375.

[8] Parker, pp.27-28.

[9] Houlding, p.373.

[10] ibid, p.376.

[11] Public Record Office, War Office Records 4/88

, Public Record Office, War Office Records 55/416 , Public Record Office, War Office Records 27/21-6

[12] Fuller, J.F.C., British Light Infantry in the Eighteenth Century, London, 1925.

[13] Houlding, p.376.

[14] Ibid, p.145.

[15] Lefferts, Charles., Uniforms of the American,

British, French, and German Armies in the War of American Revolution 1775-1783. New York

Historical Society, 1929, p.195

[16] National Army Museum MS 6807/1571/6. Maj.Gen. Howe's NIS Light Infantry Discipline, 1774. Note: The author has recently transcribed a copy of this manual, which he has used to read through the manoeuvres.

[17] Howe's, pp 19-22.

[18] Lamb, Roger. Memoirs of His Own Life. Dublin, 1811, p.89-91 & 94.

[19] Radford, Philip, ed., Dr. Honyman's journal. Huntington Library.

[20] French, Allan ed., British Fusilier in Revolutionary Boston. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 1926, p.4445.

[21] French, p.48 & p.50.

[22] Kehoe, Vincent J.R., We Were There! April 19, 1775. Privately Published, 1974, p. 117.

[23] Kehoe, p.144 & p.149.

[24] French, p.55.

[25] Ibid, pp 28-9.

[26] Elting, John., The Battle of Bunker's Hill. Philip Freneau press, N.J., 1975.

[27] Glyn, Thomas., The journal ofThomas Glyn, 1 st Foot Regiment of the Foot Guards on the American Service with the Brigade of the Guards 1776-1777. Princeton University: NIS Collection, p.9.

[28] French, Christopher, journals. Manuscript Division, Library of Congress.

[29] Novak, Greg. We have Alwavs Governed Ourselves, and I've Always Meant To. Campaign Book #7, A Guide to the American War of Independence in the North. Ulster Imports, Champaign, Ill., p.25.

[30] Atwood, Rodney. The Hessians. Mercenaries from Hesse-Kassel in the American revolution. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, p.61, also pp.82-3.

[31] Hoffman, Ronald and Albert, Peter J., ed., Arms and Independence: The Military Character of the American Revolution. University of Virginia: Charlottesville, 1984, p.202.

[32] Parker, p.90.

[33] Novak, p.101.

[34] Willcox, William B., ed., The American Rebellion: Sir Henry Clinton's narrative of His Campaigns, 1775-1782, with an Appendix of Original Documents. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1954, p.95, n.16.

Parker, p.90.

[35] Willcox, p.247, and Parker, p.91.

[36] Mackenzie, Lt. Roderick. Scriptures on Lt. Col. Tarleton's History of the Campaigns of 1780 and 1781, in the Southern Provinces of North America.... London, 1787, pp 106-115.

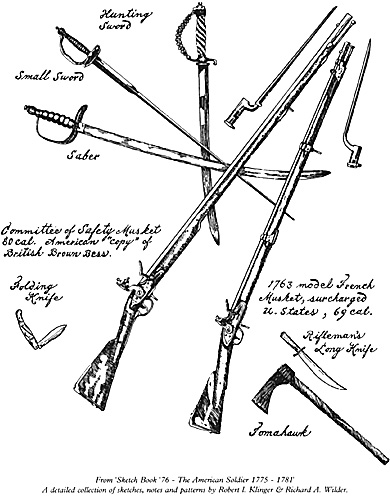

Typical Arms

Back to 18th Century Military Notes & Queries No. 10 Table of Contents

Back to 18th Century Military Notes & Queries List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 by Partizan Press

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com