This article, first appearing in THE SEVEN YEARS WAR ASSOCIATION JOURNAL, provides a brief summary of the lecture that Professor Christopher Duffy presented at the GENCON convention in Milwaukee, Wisconsin in August 1992. The lecture covered (1) the general conditions under which Frederick's battles were fought; (2) the evolution of the oblique order of battle - how it was applied with great success at Leuthen and then with diminishing returns thereafter; (3) why the oblique order produced less than desirable results; and (4) the evolution of new tactics during the Seven Years War. Professor Duffy enhanced his presentation with a slide show featuring photographs of the battle sites, battle maps, portraits and uniform plates.

PRUSSIA'S STRATEGIC SITUATION

Frederick found himself fighting a three-front war against France, Austria and Russia, so he had to rely on a strategy of interior lines, fighting his opponents one at a time. Accordingly, he did not need to annihilate the opposing armies, but merely defeat them as economically as possible and keep them off his back for a one or two month period. Frederick could win with this strategy because he had a resilient army that could fight well and cover up for Frederick's many mistakes. Later in the war, Frederick would avoid battle, for not to be destroyed was ultimately to win.

What made the Prussian army so resilient? In part, it was Frederick's genius and an attitude of never giving up, but also, the officer corps was very strong and dedicated to the Prussian state (they were predominantly from the nobility class, had high social status, and had much to lose if Prussia were defeated), as were the common soldiers, whom Duffy described as homogeneously Protestant and Prussian. Therefore the native Prussian soldier had much to lose, a nation, if they did not win the war.

Duffy contrasted the national make up of the Prussian army with the polyglot collection of ethnic groups that composed the Austrian army. Germans, Slavs, Hungarians, Italians, Walloons, etc. shared a certain degree of loyalty to Maria Theresa, but they also had their own nationalistic interests. The drill and discipline of the Prussian army made it capable of performing great feats on the battlefield and also contributed to the resilience of the army after massive defeats such as Hochkirk and Kunersdorf. Finally, Frederick's ability to communicate with all of his men contributed to the army's spirit and resilience. Frederick felt that it was the duty of all officers to talk to their men and he set the example in this area. Again, Duffy compared this to the indifference that Austrian officers generally displayed towards their men.

THE OBLIQUE ORDER

THE OBLIQUE ORDER

Given Prussia's numerical disadvantage in manpower, Frederick wanted to avoid the conventional form of near linear warfare, which was often costly and indecisive. Drawing inspiration from history (the Battle of Leuctra 371 B.C. and the writings of Vegetius). Frederick recognized the merits of concentrating his army on one wing of his opponent in order to give the Prussian army a local advantage in numbers. One interesting note presented by Professor Duffy was his contention that the Austrians were aware of Frederick's use of the oblique order as early as 1745. If this is true, it either speaks well for the Prussian army's ability to out-manoeuvre the Austrians prior to the battle or it reflects poorly on the Austrian generals' inabilities to respond to the tactical situations on the battlefield.

Professor Duffy then discussed the features of the oblique order battle tactics as practised by Frederick. These were (1) the approach march around the enemy flank, (2) the deployment of the army, and (3) the reconnaissance and pre-battle briefing.

The purpose of the approach march was to bring the army around the flank or rear of the enemy. It exploited the superior marching ability of the Prussian armv, and by default, the Austrians inability to quickly respond to the Prussian movement.

The deployment of the army was critical, in terms of where and of the timing of the deployment. Duffy points out that it is impossible to control the action and movement of the army once the battle begins. It was easier to manoeuvre columns of troops prior to the battle than it was once the fighting began. Applying this to wargames, we might consider rules that require infantry battalions to remain in line formation, facing straight ahead once they deploy from march column to line formation.

The reconnaissance of enemy positions and prebattle briefings were also critical to battle success, especially given the inability of commanders to control the troops once the action began. The attacker has to gain his advantage before the shooting starts. Frederick would typically conduct a personal reconnaissance of the enemy position and then brief his officers about what he wanted them to do. This phase could vary from a few minutes to several hours. Once a decision was made though, the final briefing took but a few minutes. For one thing, Frederick's officers had been with him for as much as fifteen years, and they understood their duties from experience.

OBLIQUE ORDER APPLICATIONS

Professor Duffy then discussed the application of the oblique order to such battles as Lobositz (an unplanned encounter battle), Prague (mixed results due to faulty reconnaissance), Kolin (a failure in tactics), Rossbach, and Leuthen (oblique order applied to perfection). This was probably the most enjoyable part of the lecture, because Professor Duffy hauled out his battle maps and gave us a fascinating step by step battle commentary and critique, complete with a number of amusing anecdotes and personal opinions. To give you a few examples, Duffy continually referred to the Austrians as "the good guys" and the Prussians as "the bad guys in black" and a decidedly pro-Austrian audience cheered in agreement.

I felt very alone in my pro-Prussian sympathies. Professor Duffy debunked the story of Prince Henry heroically inspiring his men to attack at Prague by personally wading into the stream in front of his battalion. More likely, asserted Duffy, Prince Henry found the bank of the stream to be steep and slippery and he fell into the drink. Our good friend knows this to be true from personal experience when he visited the site and performed an accidental reenactment of the incident. Another example of Professor Duffy's humour was in his reference to the battle of Kolin as "a great day for humanity." Even I got a good chuckle out of that comment.

In discussing the application of the oblique order in the early battles, it quickly became clear that it was a difficult strategy to execute and only worked as planned at Leuthen, where all the conditions were perfect for success. At Prague, Frederick was ill and assigned the reconnaissance to von Schwerin, who failed to see that the open ground on the Austrian right was in fact a series of bogs and drained ponds that would hinder movment.

At Kolin, miscommunication turned a flank attack into a frontal assault up a gradual open slope.

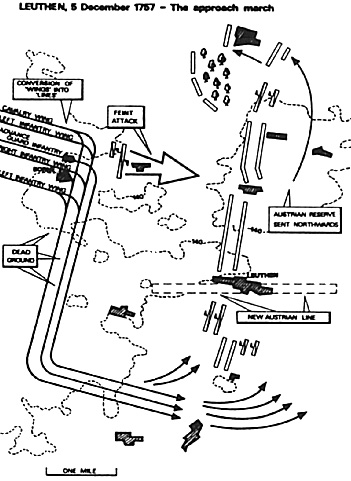

It was only at Leuthen, where the oblique order was successful and it would not be repeated again to that degree during the rest of the SYW. For one thing, the Prussians had conducted their annual peace-time army manoeuvres on the Leuthen battle site and they knew the ground very well. In addition, the decisive cavalry action won by the Prussian advance guard at Borne, left the Austrian commanders blind to the flanking march that was crossing their very front.

This in turn caused the Austrians to believe that the feint attack of the Prussian advance guard towards the Austrian right was the primary attack. In response, the Austrians committed their heavy cavalry reserves to this sector of the battlefield instead of leaving them where they could have met the real attack on their left.

Thirdly, the Austrian troops on the left were "decidedly dodgey" and inferior in quality to the Prussians. These troops were, of course, the Wurttemburg and Bavarian allies. Frederick had expected to find the Austrians dug in behind field works, so he brought a number of siege cannons to the fight and these administered a heavy toll on the Austrian infantry deployed in the open. Finally, Frederick took his time in the pre-battle briefing, speaking to every battalion commander and taking his time in deploying his troops. This was a lesson learned from the disaster at Kolin.

DIMINISHING RETURNS

After Leuthen, the oblique order produced diminishing success for Frederick's army. At Zorndorf, Kunersdorf and Torgau, Frederick supposed that he was marching around the rear of his enemy, when in fact he ended up attacking the opponent's heavily fortified front. At Zorndorf, the approach march was highly successful, but the Russians were accustomed to fighting the Turks in an army square formation, which when used at Zorndorf, enabled them to "about face" and fight off the Prussian frontal assault. A bloody Prussian attack failed and only Seydlitz's cavalry action saved the Prussian infantry from defeat. The battle was a draw at best. Both Kunersdorf and Torgau are examples where a long and tiring flank march found the Prussians facing and attacking the strongest enemy position, with disastrous results.

WHAT WENT WRONG

Professor Duffy opined as to why the Prussian tactics no longer seemed to work. He attributed these failures to:

- (1) a vast improvement in the calibre of the Austrian army.

(2) the effect of rigorous flank marches on the Prussian troops. A 15-18 mile march in high summer through difficult terrain exhausted the men before they even got into action.

(3) the delay in attacking imposed by the reconnaissance lost time at a critical state in the battle, allowing the opponents to react to the flank march.

(4) ignorance of the terrain often surprised the Prussians once the attack began. Prague, Kunersdorf and Torgau are prime examples.

(5) ignorance of the enemy deployment often resulted in an attack on the enemy's strongest position.

(6) the declining quality of the Prussian troops during the war.

NEW TACTICS AND ALTERNATIVES

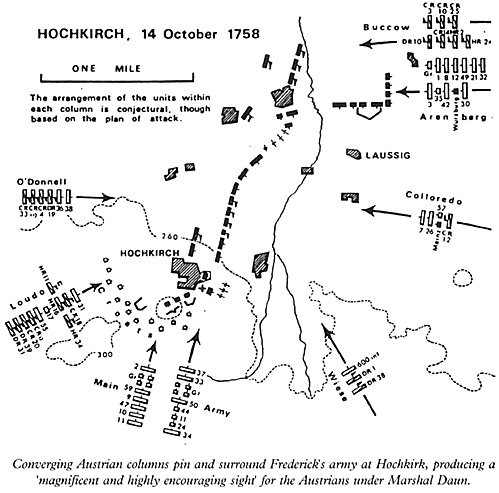

While the flower of the Prussian infantry was being cut down in numerous frontal attacks, the Austrians were adjusting to the Prussians and trying out some new concepts. Chief among these was the concept of converging columns of attack from different directions. At Hochkirk in 1758, Daun divided his army into eight columns (foreshadowing Napoleonic army corps) of combined arms and attacked the Prussian position from three directions. For once, the Austrians did not use their superior numbers in one long, inflexible battle line, but instead, pinned the front of Frederick's army and attacked the Prussian flank and rear. Professor Duffy termed the ensuing Prussian rout as a "magnificent and highly encouraging sight." He demonstrated how the Austrians used similar tactics again at Maxen in 1759 and showed how Prince Henry of Prussia won the battle of Freiburg in 1762 using the same tactics.

Frederick's new ideas were limited to the use of massed artillery batteries late in the war. At Burkersdorf in 1762, a 55 gun battery annihilated the Austrian infantry and was followed up by a Prussian counter-attack through the resulting hole in the Austrian line. This too foreshadowed certain aspects of Napoleonic warfare in the early nineteenth century.

All in all, this was a highly informative and entertaining lecture delivered by the pre-eminent scholar of the Seven Years War: Professor Christopher Duffy. I can't begin to convey the amount of interesting material and anecdotes that we heard, but I hope that this article gives you a flavour for what happened. I think that I came away from this lecture with two important concepts. The first being the difficulty in controlling troops or managing the outcome of the battle once the troops were deployed; and secondly, shattering the misconception that the oblique order was an automatic key to success for Frederick.

Hochkirch Map

Converging Austrian columns pin and surround Frederick's army at Hochkirk, producing a magnificent and highly encouraging sight for the Austrians under Marshal Dann.

Back to 18th Century Military Notes & Queries No. 10 Table of Contents

Back to 18th Century Military Notes & Queries List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 by Partizan Press

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com